Introduction↑

Great War literature begins in Portugal with the first hostilities in 1914, even though the country did not enter the conflict until 1916. The complexity of the historical process that led to this military intervention was mirrored in different evolutions and scenarios in the Portuguese literary field, with a consistent concern to warn a population that was mostly illiterate and unaware of the intricacies of international politics. More than a simple cultural expression, originally this literature appeared associated with a socialising and educational mission by the handful of writers who sought to enthuse and support the Portuguese in the sacrifices necessary to conquer victory and reap the rewards.

Political and economic treatises, military essays, historical sketches, academic dissertations, conferences, fictional or lyric narratives and memoirs are many of the genres explored by Portuguese authors, civilians and military men alike. Even though the War Ministry’s censorship was active in that era, it targeted mainly the press throughout, therefore the content of these works presents a diversity of visions and reflections, both apologetic and critical. This national War Literature review will address a historical approach, in order to elucidate some of the key authors and titles, trends, engagements and allure of those writings. This kind of wartime literature has endured in Portugal until now, with new publications and re-editions being produced and gaining a new emphasis in the centenary celebration of 1914-1918.

National overview of the Great War literature throughout time↑

Due to the diversity, extension and frequency of titles that may be found in Portuguese libraries about World War I, a concise contextualization is required. On the one hand, it is necessary to emphasize the strong interconnection with the chain of historical events in Europe and Africa, where a presence in both operational theatres resulted in opposing perspectives, without losing a convergence of mutual values, principles and memories. On the other hand, it is not possible to omit the political weight and the social changes in Portugal during the 20th century: the civic and patriotic character of the First Republic (1910-1926) was diluted by the more negative vision of the Estado Novo regime until 1974, retaining the Great War agenda after the consolidation of democracy.

Between 1914 and 1916 – years of diplomatic stalemate which frustrated Portuguese interventionism – the dominant literary genre was the lyrical, with multiple odes, sonnets and poems dedicated to a Europe immersed in the war. Guerra Junqueiro (1850-1923), João de Barros (1881-1960), Armando d'Araújo (1878-1962), José Nunes da Mata (1849-1945), Maria O'Neill (1873-1932), etc., voiced their support for the embattled demo-liberal nations and their opposition to Germany, which was blamed for the worldwide conflict. Among other non-literary records, one could observe a strong presence of writers connected to the republican cause encouraging national participation alongside the Allied armies.

Following the German declaration of war, the Ministry of War supported the publication of Cartilha do Povo - 1.º Encontro: Portugal e a Guerra (June 1916), a propaganda booklet by Jaime Cortesão (1884-1960). In a colloquial dialogue, easily understood by the illiterate public, three characters discuss the arguments for the country’s presence in the Great War: «João Portugal» (the metaphor for homeland), «José Povinho» (the people) and his son «Manuel Soldado» (an Army soldier). Together they praise the values of liberty, patriotism, diplomatic commitment and the defence of the African colonies against German despotism.

A similar message will prevail in follow-up publications like Cartas da Guerra (1917) by Adelino Mendes (1878-1963) and, in the following year, the poem Soldado que vais à Guerra by António Correia de Oliveira (1878-1960) or Em tempo de Guerra by Ana de Castro Osório (1872-1935). Even children's literature got slightly involved in the trend with De como Portugal foi chamado à Guerra (1918) of the latter or Portugal e a Guerra: manual para crianças (1917) by Tomás de Noronha (1870-1934). Works such as these competed for the publishing market with compilations of journalistic articles by different personalities in favour of the war effort such as Francisco Homem Cristo (1860-1943), António Sardinha (1887-1925) and Manuel de Brito Camacho (1862-1934), still arguing over colonial or full participation.

However, soon the focus would shift to the literary memoirs of returning veterans, a popular genre between 1917 until circa 1925. Such works were either self-published or promoted by large editorial companies, especially the cultural and civic movement of Renascença Portuguesa, which had always championed military intervention. It is no wonder that 1919, when the Allied victory was ratified and world peace seemed at hand, was the most prolific year for this segment of Portuguese Literature. Memoirs, drama, fiction and poetry flooded the market in a mainly pro-European celebration that persisted in years to come due to readers’ concerns. With the transition to authoritarian governments, the theme of the Great War lost most of that commercial value, whether because it was associated with the now-deposed republican regime, or because it perpetuated the memory of incidents that were not always sources of pride for the Portuguese Army. In this new setting, devoid of criticism, the 1918 Battle of La Lys went from military disaster to shining example of the bravery and spirit of the Portuguese soldier.

The number of published and re-edited works became residual, even though it was never eliminated by censorship or superseded by literature about the Colonial War (1961-1974). Eventually, the centenary gave way to a new increase in the literature about World War I, through the publication of long-sold-out titles, and the appearance of manuscripts previously held in private and public archives, some already available at web portals dedicated to this subject.

Literature of the African front↑

Military campaigns in Africa, where the expeditionary forces served longest and at the greatest human cost due to tropical diseases and sanitary flaws, did not translate into the most extensive wartime literary production. This is especially true of the classical literary forms, since other types of writing had considerable impact, notably medical scientific studies about the various military expeditions to Angola and Mozambique. Alongside these stood military essays such as A Mentira da Flandres e …o Medo! (1922) by J. Ferreira do Amaral (1876-1931) and A guerra nas colónias: 1914-1918 (1925) by Gen. Gomes da Costa (1863-1929), which demonstrated the need to improve recruitment and operational capacity in order to ensure the defence of Portuguese Africa for years to come.

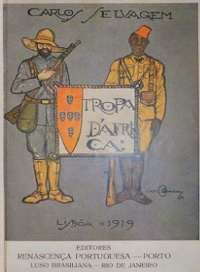

The first volume of personal memoirs that stands out is Artur Patrício’s Impressões da viagem a bordo do "Moçambique" ao Sul de Angola (1915), followed up by Tropa d’África (1919) – written by Carlos Selvagem (a pseudonym of Carlos dos Santos (1890-1973)) – and Memórias de um velho marinheiro e soldado de África (1941) by J. Azevedo Coutinho (1865-1944). All three narrate the personal experiences of months in African territory, revealing a personal struggle between the sense of duty and a feeling of abandonment by their country in extremely harsh living conditions, whose consequences were never properly addressed during the campaign itself and after their return.

A stronger criticism may be found in Epopeia maldita: o drama da guerra d'África (1924) by António de Cértima (1894-1983) and Na costa de Àfrica (1932) by A. Pires de Lima (1886-1966), both of which caused great controversy when published. The first, due to its call for an urgent self-reformulation of the Portuguese mission in the colonies, as well as the exposure of the shockingly dubious decisions of military authorities, their failure to secure the borders and their condescending paternalism towards African expeditions; the second, because its author, a medical officer, painted a very harsh portrait of the total disorganization of the Army’s sanitary services, which lacked medicines, vaccines, food and even mosquito nets. More recently, O Olho de Hertzog (2010) by João Paulo Borges Coelho, transformed this framework of military incursions and post-war developments in Mozambique into a fictional story based on historical records, the same background recalled in Joaquim Alves Correia de Araújo’s (1889-1971) memories Moçambique na I Guerra Mundial: diário de um alferes-médico (2015).

Literature of the European front↑

Meanwhile, the Portuguese Expeditionary Corps (C.E.P.), present on the European battlefront for just over two years, from the beginning of 1917 to its demobilization in 1919, emerges as the main protagonist of Portuguese literature produced about the Western Front. A truly collective character, reinforced by the brotherhood and mutual support of the soldiers, turned it into the face of the national intervention abroad. If, on one hand, the C.E.P. sustained the sacrifices demanded from it by the Allies, on the other it was celebrated by society for the diplomatic triumphs it had achieved. These writings combine the adversities and anguish experienced in the trenches with the patriotism and heroism of the men who fell, often despised by the main national figures.

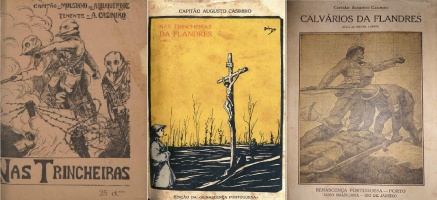

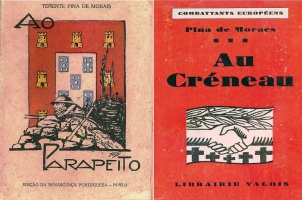

Once again personal memoirs serve as both pioneer and the most representative genre, from Nas Trincheiras da Flandres (1917 – 5 editions) by Augusto Casimiro (1889-1967) to O Bom Humor no C.E.P. (1944) of Mário Afonso de Carvalho (1887-1950). Among the more than twenty-five publications thus catalogued, the most famous is A Malta das Trincheiras (1918 – 8 ed.) by André Brun (1881-1926), a compilation of small humorous narratives and episodes in the trenches which did not fail to address, however, the often tragic and epic nature of life at the front. A similar tone was struck by Ao parapeito (1919 – 4 ed.) by João Pina de Morais (1889-1953), João Ninguém, soldado da Grande Guerra (1921 – 3 ed.) by Meneses Ferreira (1889-1936), Memórias da Grande Guerra (1919 – 2 ed.) by Jaime Cortesão and the recollections of the lives of José Maria Hermano Baptista: um herói na Primeira Guerra Mundial (2006 – 2 ed.) and António Pereira dos Santos (1895-1976) in De Chaves a Copenhaga: a saga de um combatente (2008 – 2 ed.).

Just as on the African front, more blame was heaped on Portuguese political and military authorities than on the enemy beyond no-man's land. A few authors recognized the care and humanitarianism experienced in the German POW camps, as it is clear in Da Flandres ao Hanover e Mecklenburg (1919 – 2 ed.) by Alexandre Malheiro (1870-1948) (who also published the single play O Amor na Base do C.E.P. in the same year) and in Jornal d'um "prisioneiro de guerra" na Alemanha (1919) by Carlos Olavo (1881-1958). From the mass of poetry evoking these hard times stands out Trincheiras de Portugal (1919 – 5 ed.) by J. Silva Tavares (1893-1964), Névoa da Flandres (1924) by Barata da Rocha (1891-1956) and Trovas da Flandres (1924) by António Pires Antunes (1896-1954).

Although some of these writers later turned to popular fiction with the European war as background, many civilian authors produced narratives about Portuguese soldiers in the trenches. Such works were based on the oral testimonies of returning veterans and the news that circulated in the national and foreign press. Worthy of mention are Sob a metralha (1918) by Humberto Beça (1878-1924), Episódios da Guerra (1919) by Amélia Cardia (1855-1938), Pão Vermelho (1923) by the Viscount Vila Moura (1877-1935) and Joaquim Ribeiro de Carvalho’s (1880-1942) Maldita seja a Guerra… (1925). Nowadays, the theme has received new attention among fiction writers such as José Rodrigues dos Santos’ A Filha do Capitão (2004), Memória das Estrelas sem Brilho (2008) by José Leon Machado, Os Olhos de Tirésias (2013) by Cristina Drios or J.F. Matias’ A Guerra do Salavisa (2014). In these works, facts are manipulated in order to highlight the Allies’ valour and martyrdom in their common fight for freedom, as well as the well-deserved respect and affection towards the C.E.P. as a powerful national symbol.

The impact of wartime literature↑

One of the idiosyncrasies of this literary subgenre was its breakthrough role in the enhancement of Modernism in Portugal, where Renascença Portuguesa was the first to showcase it widely to the general public. Besides a special number dedicated to the Great War in its magazine A Águia (2nd trimester of 1916) – with collaborations by some of the most famous cultural figures such as Teixeira de Pascoaes (1877-1952), Raul Proença (1884-1941), Teófilo Braga (1843-1924) or Augusto Gil (1873-1929) – a great part of its editorial program was devoted to war-related books and pamphlets. By 1924, a total of eighteen titles were published by a roll-call of emerging and best-selling authors like Basílio Teles (1856-1923), Vila Moura, Alexandre Malheiro, Pina de Morais or Augusto de Casimiro, the latter being the most prolific of all, with five bibliographical entries in total.

Following this path, other pioneering magazines such as Illustração Portuguesa, Orpheu, Portugal Futurista, Seara Nova, Contemporânea ou Presença sponsored a new generation of writers and intellectuals who sought to renew national culture during the first half of the 20th century. Mário de Sá Carneiro (1890-1916), Raul Brandão (1867-1930), Leonardo Coimbra (1883-1936) or Almada Negreiros (1893-1970) were enrolled in this panorama of wartime literature, likewise Fernando Pessoa (1888-1935) with works like the poem O menino da sua mãe (1926) or even the scathing Carta a um Herói Estúpido (2010). Without forgetting a small female contribution, this magazine publishing market supported an artistic renovation with illustrations by rising names of the avant-garde art movement.

Ironically, some of these Portuguese creators who are internationally known today had little influence at the time. Some were known only for their perceived eccentricities, while, generally speaking, few people understood the innovative contributions that their writings would make to the national literature. Conversely, authors who are less recognized today were the most advertised and read at the time, appreciated for their essentially conventional style and realistic gaze through different textual modalities: João Chagas (1863-1925), H. de Assis Gonçalves (1889-1978), Aires de Ornelas (1866-1930), José Brandão (1890-1974) etc. The emphasis on the civic and patriotic mission of World War I involvement and the catharsis of war experiences and memories in loco held peoples’ attention for quite a few decades.

Despite sharing a common set of worries and defeats, the veterans of African expeditions chose a more detached and critical mindset, while the C.E.P. veterans embraced a more emotional and intimate outlook. African memoirs contain a serious warning to society about an imperative need for a shift in the colonial paradigm. Germans were not the main enemy but rather the «desk-bound Africanists» (i.e. the political and military authorities in Lisbon), out of touch with the reality overseas. For instance, maritime and overland journeys were carried out in unhygienic conditions, those in charge oblivious to some basic effects of tropical climate on human welfare. Troops were housed in isolated and marshy campgrounds which caused epidemics of inconceivable proportions that claimed more lives than the few military clashes that took place. Therefore, the military catastrophe in Africa was the responsibility of poor decision-making, a situation that stood in stark contrast to the proclaimed public image of a well-established colonial power.

Meanwhile, in European testimonies, authenticity and empathy were combined to provide an emotion-driven depiction of life in the trenches. The audience is confronted with the war as seen through the eyes of its participants: their reflections on events and their own human condition in times of war; the heroic and stoic spirit of the soldiers; the increase of homesickness for families and warm weather; the behavioural differences vis-a-vis other Allied troops; and the attempt to recreate Portuguese customs at the front. Personal reflections sat alongside accounts of the neglect experienced once the government of Sidónio Pais (1872-1918) took over (December 1917-1918) and the C.E.P. was effectively dismantled, along with the British High Command after the battle of La Lys. Also palpable was the prejudice and discrimination experienced as the representatives of a country largely unknown to the majority of their brothers in arms.

Later on, Portuguese literature on the Great War reconciled two different currents: the literary and historical dimension of Portuguese intervention and the process of psychic catharsis for many of its authors. Rather than recording mere testimonies and memoirs, authors sought to provide a coherent foundation for the military events that took place, namely the challenges met and achievements accomplished by the African expeditions and the C.E.P., alongside the overcoming of both war traumas and the social alienation experienced in the conflict’s aftermath. They thus explored emotions, fears and internal conflicts never truly resolved by military decorations, commemorative monuments or public ceremonies of homage.

Conclusion↑

The potential of Portuguese wartime literature as a field of study is not exhausted in the bibliographical and authors references mentioned, nor in the critical examinations that appear in this summary of genres and literary styles, themes and places, real and fictional characters. Nevertheless, some transformative elements must be highlighted, given their importance both to the literary canon and the historiographical discourses of what was one of the key moments for 20th century Portugal.

The first relates to the national publishing market, which had its peak during the war and the 1920s but never truly disappeared, stimulated by commercial and authors’ publication and continuing up to the present day. This staying power is remarkable, considering the country’s low literacy rate at this time and afterwards (around 29,5% in 1920 and 67% in 1960), its limited consumer market and the controversial nature of the subject. Despite Portugal’s peripheral geographic position and status as a latecomer to war, this type of literature was noticed abroad, with some complimentary references in leading foreign journals. Le Portugal et la Guerre: un peuple qui a voulu et qui ve[u]rt se battre contre l'Allemagne by Paulo Osório (1882-1965) (Payot & C.ie, 1918) and Pina de Morais’ entry – translated as Au Créneau – was published as part of the «Combatants Européens collection» (Librairie Valois, 1930).

The prevalence of memoirs and autobiographical narratives of the Portuguese expeditionary force members on both fronts was in line with developments in other belligerent countries. The need to preserve lived experience in all its complexity shines through most of these works, the writers’ memories enabling the construction of a dialectic between the past and the present that extends to the yearnings of the future, in a philosophical and historical cogitation on the destinies of Man and Nation.

As a rule, two essential characteristics are shared by all these national authors: a Europeanist outlook on the conflagration, with praise for C.E.P. diminishing the importance of the African campaigns, and moderation in the description of the events that took place between professional and enlisted soldiers. The former were constrained by discipline and the need to protect the Portuguese Army’s honour, resulting in the avoidance of controversial issues and practices that might have led to its loss of face. The latter, however, dared to uncover these sensitive points and all the catastrophes and inhumanities in the African bush or in the European trenches without fear, writing from a consciously civic standpoint so that the errors would not be repeated and the merits of the old combatants forgotten.

Finally, one should note the great value of this Great War literature for the renewal of the historiographical coverage of Portugal’s military intervention. In this, memorialist narratives are joined by a significant set of historical sources in several books: photographs, reports, maps, drawings, etc. This double historical and literary legacy transports us to other complementary realities, much more intimate, emotional and realistic than the ones registered by the official texts, offering other meanings for a better understanding of Portuguese experiences of World War I.

Francisco Miguel Araújo, CITCEM/Universidade do Porto

Section Editor: Filipe Ribeiro de Meneses

Notes

- ↑ Osório, Ana de Castro: De como Portugal foi chamado à guerra. história para crianças [How Portugal was called to war. a story for children], Lisboa 1918, pp. 97.

- ↑ Rocha, Alfredo Barata: Névoa da Flandres [Flanders Mist], Porto 1924, pp. 55.

- ↑ Selvagem, Carlos: Tropa d’África [Africa's Troop], Porto 1919, pp. 33.

- ↑ Brun, André: A Malta das Trincheiras. migalhas da Grande Guerra 1917-1918 [The Trench Chaps. 1917-1918 Great War’s schreds], Lisboa 1918, pp. 47.

- ↑ Cardia, Amélia: Episódios da guerra [War episodes], Lisboa 1919, pp. 6.

- ↑ Casimiro, Augusto: Nas trincheiras da Flandres [At the Flanders trenches], Porto 1918, pp. 253.

Selected Bibliography

- Araújo, Francisco Miguel: Reminiscências nacionais da Grande Guerra. As edições literárias da 'Renascença Portuguesa' (1916-1924) (National remembrances of the Great War. The 'Renascença Portuguesa’s publishing project (1916-1924)), in: Cadernos de Literatura Comparada 31, 2014, pp. 83-110.

- Brandão, José: Notas subsidiarias para uma bibliografia portuguesa da grande guerra (Subsidiary notes for a Portuguese bibliography of the Great War), Lisbon 1926: Tipografia Minerva.

- César, Vitoriano José: Bibliografia da grande guerra. Resenha das publicações portuguesas (Bibliography of the Great War. Review of Portuguese publishing), Lisbon 1922: Tipografia da Escola Militar.

- Correia, Silvia: Entre a morte e o mito. Políticas da memória da I Guerra Mundial (1918-1933) (Between death and myth. Politics of memory of World War I in Portugal (1918-1933)), Lisbon 2015: Temas e Debates.

- Leal, Ernesto Castro: Memórias da Grande Guerra (1914-1918) na Renascença Portuguesa (Memories of the Great War (1914-1918) in 'Renascença Portuguesa’), in: Revista Cogitationes 1/3, 2011, pp. 4-18.

- Leal, Ernesto Castro: Memória, literatura e ideologia. Saudade, heroísmo e morte (Memory, literature and ideology. ‘Saudade’, heroism and death), in: Afonso, Aniceto / Gomes, Carlos de Matos (eds.): Portugal e a Grande Guerra, 1914-1918 (Portugal and the Great War, 1914-1918), Vila do Conde 2013: Verso da História, pp. 559-567.

- Marques, Isabel Pestana: Das trincheiras, com saudade. A vida quotidiana dos militares portugueses durante a I Guerra Mundial (From the trenches, with ‘Saudade’. Daily life of Portuguese troops in World War I), Lisbon 2008: A Esfera dos Livros.

- Revez, Ricardo: Escritores da Guerra. Da Renascença ao Modernismo (War's writers. From ‘Renascença’ to Modernism), in: Jornal de Letras, Artes e Ideias 1145, 2014, pp. 7-8.