Introduction↑

As World War I was ending in 1918, the proposal to institute a League of Nations was gathering strength among the Allies. The Japanese at this time tended to dismiss this talk as wartime rhetoric and their government was focusing on ways to secure the territorial spoils of war and increase Japan’s standing among the nations of the world. Except for a few liberal academics, there was none of the groundswell of public enthusiasm for a global peace organization that was seen in England and America. When specifics of the League proposal were aired in the Japanese press, the overwhelming response was fear that an international body would act as a status-quo device to restrain up-and-coming nations and sustain the world dominance of the war’s Euro-American victors. One Japanese who voiced this protest was Konoe Fumimaro (1891-1945), a young scion of the imperial family and future prime minister. He warned in a popular monthly that unless the peace conference recognized racial equality and opened all colonies to free trade, Japan “might someday be compelled like Imperial Germany to break loose from its confinement.”

In the five decades since the Meiji Restoration (1868), Japan had undergone far-reaching political, social, and economic reforms. During the Great War from 1914, the nation had transitioned from light industry to heavy industry, supplying arms to some of the Allies at war in Europe. A military rising star, Japan had an alliance with Great Britain and in 1905 had defeated Russia, a major European monarchy, in a hard-fought war. Yet Japanese policy makers had not forgotten the Triple Intervention, where in 1895 a coalition of European states had forced Japan to give up some of the spoils of its victory in a war with China. In the opening year of World War I, Japan, with token Allied support, had taken over the German leasehold in China’s Shandong Province and German archipelagoes in the South Pacific. As the Paris Peace Conference of 1919 approached, Japan positioned itself diplomatically to prevent any scheme of the Allied powers from stripping Japan of its wartime gains and stunting its rightful growth as the regional hegemon of East Asia.

The Japanese plenipotentiaries arrived at Paris clearly unprepared on the question of the League of Nations. Japan presumed that the peace conference would conduct a division of the spoils. Japan alone among the Big Five allies had not formulated a draft constitution for the League, whereas among the leaders of the peace conference the Hurst-Miller draft had achieved template status and would prove difficult to change during the parlay.

Amending the Covenant↑

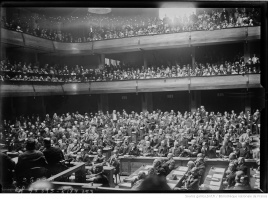

The Japanese delegation, headed by former Prime Minister Saionji Kinmochi (1849-1940) and diplomat Makino Nobuaki (1861-1949), attempted to alter the draft Covenant of the League so as to lessen its restrictions on Japan’s growth as a power. These efforts targeted with some success the disarmament and sanctions provisions of the League’s constitution. Also of concern to Japan were the provisions of the International Labor Convention, drawn up at the Peace Conference to advance labor rights and to inscribe world labor standards in the League-linked International Labor Organization (ILO). Japan found comradery with India in securing special treatment for developing economies. Most memorable in Japan’s effort to influence the formation of the League of Nations was the Japanese-led endeavor to insert a statement of racial non-discrimination in the Covenant’s preamble. Australia feared unlimited Japanese immigration and senators from the southern states of the US were loath to allow any challenge to race relations there. The United States of America and Britain machinated the defeat of Japan’s proposal despite the support of France, Italy, and China.

In the end, Japanese concerns for stable relations with trading nations and for securing former German rights in Shandong swayed the Seiyūkai Party cabinet to affirm the postwar settlement including its League of Nations. Japan assumed a prominent position in the organization as one of the four permanent members of the League Council and the leading voice for Asian constituents.

Japan in the League↑

As a non-European, major nation member, Japan was positioned to play an influential part in mediating the settlement of European territorial disputes addressed by the League, such as the Polish Upper Silesia case (1921). Japan also played assertive roles in the Permanent Mandates Commission, the International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation (ICIC), and the Opium Committee. The ILO and the Permanent Court of International Justice saw effective Japanese participation. Some of Japan’s most talented diplomats, intellectuals, and jurists held League positions in Geneva. Ishii Kikujirō (1866-1945), ambassador to Paris, sometimes served as Council president. Ishii had a part in drafting the Geneva Protocol (1924). Undersecretary- General Nitobe Inazō (1862-1933) established the ICIC, the predecessor of today’s UNESCO. Diplomat Sugimura Yōtarō (1884-1939) followed Nitobe as Undersecretary-General and headed the Secretariat’s sensitive Political Section. Adachi Mineichirō (1870-1934), who succeeded Ishii as ambassador to Paris in 1928, was a noteworthy jurist on the Permanent Court of International Justice, serving as its president for three years.

At home, political party cabinets furthered internationalist policies throughout the “Taishō democracy” decade of the 1920s and popular interest in the activities of the League was strong. In the first year of Japan’s membership, the Foreign Ministry provided financial backing for the establishment of the Japan League of Nations Association. Its early members included scholars, journalists, and diplomats who had visited war-ravaged Europe at the time of the peace conference. Shibusawa Eiichi (1840-1931), a retired industrialist, officiated as its founding president until his death. The organization’s journal, Kokusai Renmei [League of Nations], carried each month a synopsis of current activities of the Assembly, the Council, and the subsidiary organizations in Geneva and served as a leading mouthpiece of internationalist thought in a decade when taisei junnō [conformity to world trends] was the guiding principle of Japan’s foreign relations. The Association’s rolls topped 11,000 in 1932 and its membership constituted one of the world’s largest consumers of League publications.

Alienation from the Geneva Order↑

While Japan demonstrated in Geneva a genuine posture of global cooperation, most of the League’s deliberations were Europe-centered. The Japanese press sometimes referred to the League of Nations as a “European club.” Events in the West in the 1920s convinced realist Japanese thinkers that the powers were prone to circumvent the League in matters of vital self-interest. Naval disarmament was accomplished not in Geneva, but at the 1921-22 Washington Conference. The 1923 Corfu Incident, an island dispute between League members Italy and Greece, was settled by the Conference of Ambassadors rather than League machinery because Italy refused to accept the League’s jurisdiction in the case. In 1925 a set of significant political and military accommodations with Germany was concluded by Britain, France, Italy, and Belgium at the Locarno Conference. Though elaborate efforts were made to incorporate the Locarno Pacts into the League system, it was obvious that the even the European powers were prone to present the League with a fait accompli of understandings forged elsewhere. To Japanese realists, the model of Locarno seemed preferable to the League order because it was political rather than idealistic and regional rather than universalistic. The League’s most damning flaw in the eyes of Japanese was the absence of their most powerful Pacific neighbors – the Soviet Union and the USA – from its rolls. Geneva was incapable of providing an effective security framework for Japan.

In the late 1920s, the spread of the Nationalist movement in China, the growing military strength of the Soviet Union, and the global depression brought new challenges to Japan’s predominance in East Asia. In 1931, Japanese army units along the South Manchurian Railway initiated an invasion of northeast China, then known as Manchuria, which eventuated in the 1932 creation of a Japanese puppet state, Manchukuo. The Japanese press and public cheered what was envisioned as a model for the reconstruction of China under Japanese guidance. China brought the charge of aggression before the League of Nations. The Assembly, by a vote of 42 to 1 (Japan), ruled that Manchukuo had come into being not by the will of the people of Manchuria but by the action of the Japanese army. In response, Japan in March 1933 announced its withdrawal from the League of Nations. But the organization applied no economic or military sanctions against Japan. Japan continued to participate in the ILO, the ICIC, the Opium Committee, and the League’s Health Organization. When Japan launched its New Order in East Asia in 1938, these residual ties to the League were terminated.

Out of the ashes of World War II and the ignominy of the Allied Occupation emerged a Japan determined to conduct its diplomacy in consonance with the international community. Once sovereignty was restored to Japan in 1952, Japan applied to join the United Nations. It so happened that many of the foreign policy makers and practitioners of the reconstituted nation had career experience with the League of Nations. For postwar Japan, the values inculcated in the Geneva years were not lost.

Thomas W. Burkman, University at Buffalo

Reviewed by external referees on behalf of the General Editors

Selected Bibliography

- Burkman, Thomas W.: Japan and the League of Nations. Empire and world order, 1914-1938, Honolulu 2008: University of Hawaii Press.

- Dickinson, Frederick R.: War and national reinvention. Japan in the Great War, 1914-1919, Cambridge 1999: Harvard University Press.

- Nish, Ian Hill: Japan's struggle with internationalism. Japan, China and the League of Nations, 1931-1933, London 2000: Routledge.

- Shimazu, Naoko: Japan, race, and equality. The racial equality proposal of 1919, London 2009: Routledge.

- Thorne, Christopher: The limits of foreign policy. The West, the League and the Far Eastern Crisis of 1931-1933, London 1973: Macmillan.

- Xu, Guoqi: Asia and the Great War. A shared history, Oxford 2017: Oxford University Press.