Introduction: From “Coolie Corps” to the Indian Labour and Porter Corps↑

Among the dizzyingly diverse ranks of Indian non-combatants were the departmental followers who made up the medical, ordnance and transport services, and public and private regimental followers who served as cooks, sweepers, water carriers, valets, blacksmiths and cobblers.[1] The follower ranks also included veterinary personnel, grass-cutters and grooms, postal workers, and the skilled and unskilled labour required by the army of occupation in Iraq for the Inland Water Transport and the running of railways.[2]

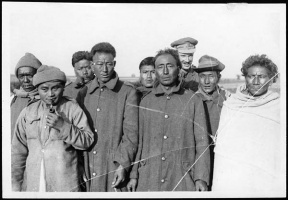

This essay focuses primarily on the “Coolie Corps”, which were not regarded as a permanent part of the Indian army. Yet they were a regular feature of military border making in India, for frontier expeditions generated a continuous demand for porters and road and railway construction labour. The Coolie Corps also accompanied expeditionary forces overseas, for instance to Abyssinia (1868), China (1900) and Somaliland (1902-04). During the First World War, those sent overseas acquired the politically more acceptable name of Indian Labour Corps and Indian Porter Corps (ILC and IPC) and the men were enlisted as followers under the Indian Army Act.

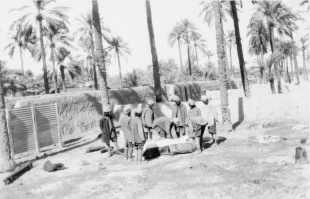

In late 1915 an IPC from Madras Presidency and two ILC from Punjab were organized for Gallipoli but diverted to Mesopotamia, where the Indian Expeditionary Force was facing an acute logistical crisis. Basra had to be reconstructed as a port to cope with the volume of seaborne supplies and flood embankments had to be erected around military bases. To send men and material up the line, rivers had to be harnessed and road and railway track laid out. Canal networks had to be deepened and extended to increase local food supplies. In 1916, to meet an acute bottleneck in labour supply, the jails of India began to be trawled using a remission of sentence scheme. Ultimately some 16,000 prisoners would be drafted into seven Jail Porter and Labour Corps in addition to 1,602 sent as sweepers or in miscellaneous units such as a Jail Gardener Corps.[3] By 31 December 1919, India had supplied 348,735 non-combatants of every conceivable category to Mesopotamia.[4] Some of these, such as the ILC and IPC positioned at Bushire, South Persia and along the Baghdad-Khanikin-Hamadan route, would also play a role in the undeclared war in Persia. In February 1917, the government of India undertook to provide 50,000 labourers for France as well, where, reorganised into units of 500, they made up the 21st through the 85th Indian Labour Companies. In October 1918 two agricultural ILC were sent to Salonika.

The signing of the armistice on 11 November 1918 did not reduce the demand for labour in Mesopotamia and Persia and ILC drafts continued to be raised between 1919 and 1921 to replace companies being repatriated. Along India’s own frontiers, the Labour Corps had to be raised to crush the Kuki-Chin uprising on the Assam-Burma border (1918-19) and on the other side for the Third Afghan War trailing into the Waziristan campaign (1919-21). At one point there were thirty-one Labour Corps stationed at Lahore, Ferozepur, Kirkee and along the North-West Frontier Province.

The Politics and Economics of Labour Recruitment: Competing Imperatives↑

The factors which aided or hampered recruitment in South Asia emerge more clearly if one takes a wider frame instead of focusing only on the movement of manpower to war theatres. This perspective also allows one to factor in the labour of women and children in “India’s Contribution to the Great War”, as for instance in fields, tea plantations, coal mines, textile mills and construction sites. In 1916, in response to bitter complaints that India, with her population of 320 million, was not supplying labour with sufficient speed to Mesopotamia, the government of India listed the problems. Open compulsion would be difficult given that it did not have the infrastructural capacity to distribute the burden fairly. The use of force to send labour overseas would also be politically disastrous given the full-blown campaign underway at the time to end the system of indentured migration from India to the empire’s sugar plantations. In addition, protests had also started to take shape against local forms of state corvée. The greatest danger was that indiscriminate recruiting might set off panic flights of labour from production sites in India and along the transport nodes that maintained supply lines to the war theatres.[5] British firms in India echoed this concern, underlining the importance of not disturbing labour at plantations, mines and tanneries. Their focus on profit margins prompted one official to ask a leading European businessman “when Calcutta was going to join the Allies”.[6]

Therefore, the army’s manpower needs always had to be balanced against other imperatives equally crucial for an empire at war: the generation of material resources, the creation of export surpluses to balance Britain’s trade deficits, and the diversion of transport infrastructure to meet military needs. For the same reason, the circulation of Indian labour around the Bay of Bengal was allowed to continue throughout the war, although on a reduced scale, because it sustained docks, mines, plantations and oil works in Sri Lanka, Malaya, the Straits and Burma. In India significant labour pools, as in Bihar and Orissa, had to be divided up between the army, the civil departments and commercial interests. Another concern was to ensure that, in crucial recruiting areas such as Punjab, harvests could be brought in and agricultural wages did not spiral out of control.[7]

What the government of India could count on was a spectrum of labour regimes, ranging from corvée to contract labour, which sustained a military construction complex along the land frontiers of India.[8] Skills generated here as well as in canal, road and railway construction under the aegis of the Public Works Department and the Railway Board were put at the disposal of the empire in Mesopotamia, East Africa and France. Engineers, overseers and artisans were also positioned behind the lines.

However, the more intensive tapping of labour nodes along India’s land frontiers also put men, information and war material into circulation between regional conflict zones and theatres of war overseas. Local officials wanting to redefine the border began to profile their ambitions in a more international frame. Some frontier chiefs and headmen seized the opportunity to expand their influence and others felt the threat of dispossession more sharply. By the turn of 1918-19 the tribal “Alsatias” between the borders of Assam and Burma, and between the North-West Frontier Province and Afghanistan were drawn into the global conflict for influence and territory.[9]

Turning seaward, one encounters the lascars, seamen who formed 17.5 percent of the pre-war British merchant marine, a figure which went up during the war;[10] and the labourers, artisans and overseers who laid out harbour works and railway track in Malaya and East Africa. The accumulation by 1914 of some 1,000 Indian labourers at the Anglo-Persian Oil Company’s works at Abadan marked the rising stakes for the empire in the Persian Gulf.[11] Arguably, the success with which Indian labour had been moved around the Indian Ocean in the empire’s service encouraged schemes to marry militarist with “developmentalist” ambitions in British-occupied Iraq.[12]

Recruitment, Termination, Reengagement↑

“Young men will get a chance to see the world in a safe job on good pay.”[13]

To distance labour recruitment for the Indian army from the stigmatized system of indentured migration, the government of India sidestepped the Indian Emigration Act, drew upon the Indian Army Act and cast the exercise as “war-work overseas”. This ensured that public scrutiny could be kept to a minimum while providing another equally rigorous disciplinary frame. However, whereas the men who served in British Labour Battalions were classed as combatants, the government of India refused, for fiscal and ideological reasons, to elevate the men of the ILC from follower to combatant rank.

In the opening phase of the war there was a reliance on regimental networks, the overseers of military market-places, and contractors with links to Military Works or to the army Supply and Transport department to generate followers. However contractors were not always able to guarantee numbers and were blamed for passing off “inferior” material. Recruitment bonuses were too low to tempt brokers in the Madras Presidency, who had links with shipping firms and supplied labour around the Bay of Bengal.

By autumn 1916, combatant and non-combatant recruitment was centralized under the Adjutant General. Quotas were allocated on a territorial basis, and revenue officials, headmen and chiefs were deployed more forcefully to assist recruiting. In certain localities, corvée was bent to meet ILC quotas, but exemption from this obligation also had to be offered as the reward for war service. In 1917, too much force used in ILC recruitment, together with other grievances, triggered an uprising in the princely state of Mayurbhanj and a prolonged insurgency in the Kuki-Chin tracts along the Assam-Burma border.

However, sharp price rises and bad harvests in 1918-19 made it easier to recruit labour. The monthly wage was fifteen rupees for the IPC and twenty rupees for the ILC, roughly comparable to the sepoy’s (soldier’s) pay with allowances. However, institutional care was inferior, wound and injury pensions were lower and if a labourer died in service his family received a one-time gratuity, not a pension. Certain aspirational currents, particularly the desire to “see Europe”, were also discernable in ILC recruitment, with some missionaries but, more importantly, first-generation literate members of certain “tribal” and “low-caste” communities acting as the conduit.

The labour companies sent to France were recruited from the North-West Frontier Province, the United Provinces, Bihar and Orissa, Bengal, Assam and Burma. The term of engagement was a year, and most companies refused to accept any formal extension of their contract. A more India-wide pattern of recruitment, and a longer presence in the theatre of war (1916-21), characterized the ILC and IPC in Mesopotamia. Here some labour units were recruited on “duration of war” agreements, which were the norm for combatants. In general, however, labourers preferred fixed terms of engagement lasting one or two years, since termination of contract was their one form of protection against a formidable employer. It allowed them to negotiate for better wages and even re-designation as skilled labour, or to shift to some other worksite, before which they sometimes took a spell of home leave.

The Institutional and Work Environment↑

Indians were not eligible for officer’s commissions. However, the government of India could supply only three British commissioned officers for every Labour Corps of 2,000 it sent to France. It therefore added civilians as supervisors over companies of 500; the supervisors were drawn from educated Indians, Eurasians and Europeans. At the lower level, Indian NCOs were appointed from the regular army. Their presence meant that in contrast to the large number of British NCOs assigned to other “coloured” labour companies, only four had to be attached to Indian labour companies in France. Headmen and mates, some chosen because of their assistance in recruitment, were appointed over groups of 240 and thirty. In Mesopotamia the IPC was composed of 800 men and the ILC of between 1,000 and 1,250 men. The shortage of British Officers for labour units was always a problem, and with the growing emphasis in Mesopotamia on payment by piecework, clerks were also required to keep accounts. In May 1918 the Directorate of Labour in Mesopotamia, hitherto supervising only local and casual labour, took over the administration of Indian labour units as well.

Labourers themselves left virtually no written record of their experience and the official record is particularly thin for the ILC and IPC in Mesopotamia. Some commanding officers (COs) in Mesopotamia, concerned about the high rate of “wastage” in their labour companies, give glimpses in war diaries of relentless work in a harsh environment, compounded by pitifully inadequate winter clothing and frequent ration shortages. The 1st PC unloaded supplies in day and night shifts at Basra in 1916 in blistering heat, exposed sometimes to shelling along the riverfront. “The attitude regarding the men of my unit as ‘niggers’”, complained their CO, “without a sense of feeling, who should be beaten and worked to a ‘stand-still’ is wrong in every way.” In September 1917 the CO noted that this unit had been on active service for two years without a single free day. By this time due to sickness and death only 200 men remained of the original 1,000 recruited from the Madras Presidency.[14] Lt. M. M. Knight, a tea planter from south India commanding a detachment of the 1st ILC, described them in October 1918 as cutting with bruised hands through shingle and gypsum to extend the Khanikin railway, a great many with no boots at all, and only one blanket apiece.[15] Medical care was non-existent at far-flung worksites in this theatre.

Bringing in labour from India reduced the pressure to forcibly exact labour from the local population in Mesopotamia, and it checked the wage increases demanded by Arab labour contractors. It ensured continuity on worksites when Arab workers left to prepare their fields for cultivation or to harvest dates, or when Kurds working on the Persian road left for the hills in summer. Finding it difficult to induce local labour around Basra to move out into the desert, they were assigned the work of unloading and loading supplies and the IPC began to be shifted to construction and other tasks. By 1919 all the PC had been re-designated as ILC. During the Arab uprising of 1920, 2,500 men from the ILC, including men of the Jail Corps, were also assigned to impromptu guard duties.

In France, Indian companies were at first assigned to stevedore work at Marseilles. Shifted up to the Third Army area, many were put on battlefield salvage, an activity rising in importance because of the submarine blockade; others were assigned to road construction, laying railway, quarrying and lumber work. Road and railway construction and timber production were vital elements in generating the logistical capacity which allowed the British Expeditionary Force to gain operational momentum, restore a degree of mobility to the Western Front and eventually overwhelm the German defensive system.[16]

The ILC was better provisioned in Europe than in Mesopotamia. However, work under conditions of extreme exposure with inadequate shelter, such as that faced by the Indian companies building an RFC aerodrome near Nancy, or overwork at sites such as the forward supply base of Abancourt, led to some outbreaks of beriberi and high rates of respiratory disease.[17]

Time-work or Task-work↑

Working hours in Mesopotamia varied between 7.5 to ten hours, but the day stretched out due both to a long mid-day break to shelter from the sun and distances between the camp and worksite. Sometimes it was only a major festival that resulted in a rest day. In France, the norm seems to have been nine hours, with some effort to get one day off in seven, even if this was not always conceded. In both theatres, hours were increased to meet a deadline or at intense phases of the war.

In Mesopotamia proposals to increase productivity circled at first around the raising of weekly work hours from forty-eight to fifty-four. The CO of the 2nd ILC suggested that work be organized by task rather than by weekly hours: “The men will always work in the middle of the day to save an hour to themselves in the evening.” In other words, the currency of rest could be used to barter for increased output. However when the task was set too high this incentive proved ineffective. The earthwork task was raised by one-sixth every day for the 1st Military Prisoner Labour Company with the understanding that this would secure the seventh day off. After a couple of days they asked for a return to the former arrangement because they simply could not cope.[18] The other method was to fix a task, then allow the men to earn extra for piecework over and above it. The practice was introduced first to the Jail Corps where the monthly wage, at ten rupees, was just half that given to the “free” ILC. In May 1918 piecework “bonuses” were introduced more generally to the ILC in Mesopotamia. The argument was that Indian labour got “spoilt” if it felt it could count on a monthly wage irrespective of output. The advantage of the system was that in the face of spiralling prices, a control could be kept on the wage bill, while ensuring an intensification of output.

In France, the Department of Labour was not permitted to offer such “bonuses” to military labour units, so it could only bargain with rest. The “employer”, for example the Royal Engineers or the Controller of Salvage, would set a task and then allow a break or earlier return for speedy completion. The issue then was fixing the task at the right level. The Department of Labour often fretted that Chinese, South African or Egyptian labourers concealed their “true” capacity for work. With Indian labourers there was a somewhat different stereotype at play, namely that they had to be allowed to plod along until they finished the task. The notion that their work hours could stretch on echoed the arguments being used in India at the time to oppose the reduction of factory work hours from twelve to ten. The contention was that Indian labour was too physically weak and too culturally attuned to a dispersed work day to intensify the pace.

Discipline: “Simplicity in Procedure Combined with Promptness”↑

The disciplinary regime for the “Coolie Corps” in India was very informal, with great reliance on summary canings.[19] During the First World War it was ruled that since the men were enlisted under the Indian Army Act, a court-martial would have to be held before awarding corporal punishment. This usually took the form of the Summary Court-Martial, a tribunal “peculiar to the Indian Army”, in which the CO was the sole presiding judge and could award a wide range of punishments, including corporal punishment up to thirty lashes.[20] The desire to keep labour “on the job” created a preference in Mesopotamia for punishments such as flogging, fines, extra work or work in fetters, rather than long terms of imprisonment that would mean a return to India. Serious disciplinary issues arose only within the Jail Corps in Mesopotamia. Local Arab or Persian labour units could put up more of a resistance to the demands made on them than imported “coolies”. However, as contracts began to draw to a close, “indiscipline” would manifest itself even in seemingly docile companies. Given the shortage of shipping and the pressing demand for manpower, military authorities both in France and Mesopotamia tended to stretch out contracts or to interpret the “end of the war” very flexibly. Repatriation did not just happen, labourers had to bring it about.

The material on the Jail Corps in Mesopotamia is, ironically, more substantial than that on the “free” ILC and IPC. It reveals a disciplinary regime of extreme harshness, with high figures for “orderly room” punishments and the frequent infliction of flogging and fines. COs blamed this disciplinary violence on the innate nature of convicts. It was in fact part and parcel of labour servitude, in which the men in the Jail Corps were often deployed for the most arduous emergency duties, experienced far more rigorous controls and received wages below those for “free” labour. Desertion was sometimes the only way to escape overwork, though officers tried to deter it with sentences of flogging and labour in shackles. However, when the Jail Corps had to be dispersed in small units over an extensive worksite, accommodations had to be made in the form of bonuses for piecework and promotions for jail-recruited overseers. On 4 December 1918, a detachment of the 11th Bombay Jail Labour Corps went on a brief strike because they had been held back to complete work on the Khalisi canal, even though their two-year agreement had expired. It was a warning to military authorities in Mesopotamia that they had to maintain some contractual honesty with “Asiatic” labour.[21]

In France, the Department of Labour’s management of all unskilled labour, white and “coloured”, in the British sector was meant to raise productivity across the board. However, the prevailing notion was that to “work” natives properly, the managerial regimes peculiar to them also had to be imported into the metropolis. Discussions about “coloured labour” were always conducted in an ethnic register that justified inferior wages and institutional care, race segregation and a harsher disciplinary regime than for white labour. The positioning of “coloured” labour at any site where they might be able to compare their output, rest days or treatment with white labour was discouraged, the assumption being that this pulled their performance downwards.

The play of comparison was even more significant between the different “coloured” labour units than between white and “coloured” labour. In the case of the ILC it also took the form of a continuous comparison between the ethnically diverse companies which composed it – Naga, Santhali, Bengali, Kumaoni, Chin, Pathan, etc. This comparison emerged from the variety of political agendas that had shaped recruitment; it fed into strategies of labour management in France and gave some labour companies more room than others to secure an acknowledgement for their services. For the Department of Labour the ILC presented yet another vexatious instance of the problems which arose when white labour had to be substituted with “primitive” or “backward” labour. However, there were elements in its upper and lower command structure for whom more long-term issues were at stake, for instance, the strengthening of “empire-mindedness”, the preservations of areas of indirect rule in the future constitutional order for India, or the stabilization of self-supporting Christian communities.[22]

The richer material on the ILC in France gives some room to assess the efforts of the men themselves to bend the process of militarization to their needs and to reframe the environments, object worlds and orders of time within which they were positioned. By creating suggestive equivalences between themselves and other military personnel they sought to lift themselves from the status of coolies to that of participants in a common project of “war service”.[23] At the same time they indicated that they had put their persons at the disposal of the state to a more limited degree than the combatant.[24]

Conclusion: The Politics of Tapping Indian Manpower↑

Most Indian political leaders had expressed their support for the war effort on behalf of the empire, but the mood shifted after the Armistice. Repressive wartime ordinances were being made permanent, the Indian army still took a huge share of post-war annual budgets and Indian military personnel were still spread out over the Near and Middle East. At the same time, to discourage Indian settlement in Iraq, British authorities had begun to deport “unauthorized Indians”, particularly peddlers and merchants.[25] Indian newspapers noted that Mesopotamia was being slotted into a history in which Indians soldiers and labourers were deployed to acquire territory for the empire but where Indian settlers were unwelcome. Figures at the more radical end of the political spectrum contended that Indian manpower should not be used to crush aspirations to self-government in dependent colonies, or in those Muslim majority areas of the Ottoman Empire which were being brought under mandatory forms of imperialism.

The Government of India worked with local notables to contain any discontent among returning military personnel, and these in turn used the situation to stretch the benefits they had been promised. Returning labourers were admitted to some of these benefits, though they missed out on some of the more substantial ones – such as family pensions in case of death, or land grants and revenue grants for “distinguished service”. In areas where exemption from corvée had been offered to soldiers and labourers as a reward for war service, both tried to get their families included in this exemption. This added to the pressure to end this form of labour servitude altogether.

Along the Assam-Burma border, where the colonial regime had a special investment in building up loyal constituencies, it made more of an effort to commemorate the war services of the ILC. Going to France to render “war service” or refusing to go has been woven into ethno-nationalist narratives in this tract, particularly those of the Nagas, Kukis and Chins. Elsewhere labour companies seemed to simply melt out of official sight. For those who went in the ILC or IPC, “war service” may have become just one more excursion among many made in search of off-farm work, although a more eventful one perhaps, exposing them to new disciplines and experiences, leaving some buried in graves overseas, bringing some back with the hazards of war marked upon their bodies, others in stronger health and with a sense of consequence in society.

Radhika Singha, Jawaharlal Nehru University

Section Editor: Santanu Das

Notes

- ↑ War Office: Statistics of the Military Effort of the British Empire during the Great War, 1914-1920, London 1919, p. 777, online: https://archive.org/stream/statisticsofmili00grea#page/776/mode/2up (retrieved: 27 January 2016).

- ↑ From the considerable literature on this theme: Metcalf, Thomas R.: Imperial Connections. India in the Indian Ocean Arena, 1860-1920, Berkeley 2008; Bose, Sugata: A Hundred Horizons. The Indian Ocean in the Age of Global Empire, Cambridge 2009; Singha, Radhika: The Great War and a “Proper” Passport for the Colony. Border-Crossing in British India, c. 1882-1922, in: Indian Economic & Social History Review 50 (2013), pp. 289-315.

- ↑ Singha, Radhika: Finding Labor from India for the War in Iraq. The Jail Porter and Labor Corps, 1916-1920, in: Comparative Studies in Society and History 49/2 (2007), pp. 412-445.

- ↑ Government of India: India’s Contribution to the Great War, Calcutta 1923, p. 98, online: http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=ior/l/mil/17/5/2383 (retrieved: 27 January 2016). A total of nineteen ILC and twelve PC were sent to Mesopotamia (Ibid., p. 92).

- ↑ Singha, Finding Labor 2007.

- ↑ Buchanan, George: The Tragedy of Mesopotamia, Edinburgh 1938, p. 90, online: http://hdl.handle.net/2027/uc1.$b746003 (retrieved 27 January 2016).

- ↑ Singha, Finding Labor 2007.

- ↑ Singha, Radhika: The Recruiter’s Eye on “the Primitive”. To France - and Back - in the Indian Labour Corps, 1917-18, in: Kitchen, James E./Miller, Alisia/Rowe, Laura (eds.): Other Combatants, Other Fronts. Competing Histories of the First World War, Newcastle upon Tyne 2011, pp. 199-224.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ For an excellent account of the crisis that overtook British merchant shipping in Bombay in 1916-17 when Punjabi sailors and stokers chose the safer and more regularly paid option of joining the Labour Corps in Mesopotamia, see Balachandran, G.: Globalising Labour? Indian Seafarers and World Shipping, c. 1870-1945, Oxford 2012, pp. 241-249.

- ↑ Tetzlaff, Stefan: The Turn of the Gulf Tide. Empire, Nationalism, and South Asian Labor Migration to Iraq, c. 1900-1935, in: International Labor and Working-Class History 79 (2011) pp. 7-27; Atabaki, Touraj: Far from Home, But at Home. Indian Migrant Workers in the Iranian Oil Industry, in: Studies in History 31 (2015), pp. 85-114. In 1918, the Anglo-Persian Oil Company secured an exemption from the Indian Emigration Act to recruit skilled labour from India, a concession that it stretched to recruit unskilled labour as well. See Singha, Finding Labor 2007.

- ↑ See Satia, Priya: Developing Iraq. Britain, India and the Redemption of Empire and Technology in the First World War, in: Past & Present 197/1 (2007), pp. 211-255, online: http://past.oxfordjournals.org/content/197/1/211.full (retrieved 28 Januar 2016). However, I feel Satia overstates her argument about the degree to which Indian nationalists subscribed to imperial ambitions in Iraq. There were Indian public figures who suggested that as a reward for war services, Indian settlers could be assigned land in Iraq and East Africa, especially so since Indians were debarred from the “white” Dominions. However, the more insistent chorus in Indian newspapers was about the drain that the Mesopotamian campaign was imposing on India’s finances, food supplies and transport infrastructure. After the Armistice there was a strong anti-imperialist current directed against French and British militarism in the Near and Middle East.

- ↑ Circular, 14 May 1917, IOR/L/Mil/2/5132, India Office Records, British Library (IOR).

- ↑ WO 95/5039. The National Archives, UK (TNA).

- ↑ WO 95/ 5277, TNA.

- ↑ I owe this insight to Dr. James Kitchen.

- ↑ Singha, Radhika: The Short Career of the Indian Labour Corps in France, 1917-1919, in: International Labor and Working Class History 87 (Spring 2015), pp. 27-62.

- ↑ 22 March 1918, 26 March 1918, WO 95/402, TNA.

- ↑ Notes for the Guidance of Officers of the Labour Corps in France, pamphlet, WO 107/37, TNA.

- ↑ Singha, Radhika: The “Rare Infliction”. The Abolition of Flogging in the Indian Army, 1835-1920, forthcoming.

- ↑ Singha, Finding Labor 2007.

- ↑ Singha, The Short Career 2015.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Interestingly, the frame of “war service” allowed the recognition, even if nominally, that Indian labourers were entitled to medical treatment, compensation for injury and structured “leisure”. These were standards of wellbeing that were acknowledged very reluctantly for Indian labour in the civil context.

- ↑ To deflect criticism, all Indian labour in Iraq continued to be cast as a military Labour Corps, even though much of it was now being used under civilian aegis. Singha, Finding Labor 2007.

Selected Bibliography

- Coates Ulrichsen, Kristian: The logistics and politics of the British campaigns in the Middle East, 1914-22, Basingstoke 2011: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Kilson, Robin Wallace: Calling up the empire. The British military use of non-white labor in France, 1916-1920, thesis, Cambridge 1990: Harvard University.

- Singha, Radhika: The recruiter’s eye on 'the primitive'. To France – and back – in the Indian Labour Corps, 1917-1918: Other combatants, other fronts. Competing histories of the First World War, Newcastle upon Tyne 2011: Cambridge Scholars.

- Singha, Radhika: The short career of the Indian Labor Corps in France, 1917-1919, in: International Labor and Working-Class History 87, 2015, pp. 27-62.

- Singha, Radhika: Finding labor from India for the war in Iraq. The Jail Porter and Labor Corps, 1916-1920, in: Comparative Studies in Society and History 49/2, April 2007, pp. 412–445, doi:10.1017/S0010417507000540.