The Pacifist↑

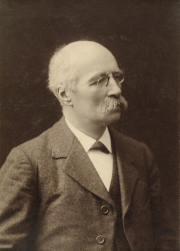

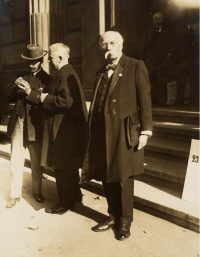

Henri La Fontaine (1854-1943) was born in Brussels in 1854, to a wealthy and progressive family. Whilst studying law at the Free University of Brussels, he developed a passion for international law, which he saw as the best way to ensure peace in the world. After graduating in 1877, he began a career as a lawyer in parallel to numerous other activities centred around peace, equality and democracy. Over the course of his career, he was able to promote these ideas within the Belgian senate, where he held a seat between 1895 and 1935; the League of Nations, where he represented Belgium in 1920 and 1921; and the International Institute of Bibliography (IIB), or the Mundaneum, which he founded along with Paul Otlet (1868-1944) in 1895, as well as in Masonic lodges. In these circles, Henri La Fontaine vigorously defended the emancipation of women, the expansion of democracy and access to knowledge for all, because he believed that peace could only be achieved in a democratic, egalitarian society.

Henri La Fontaine ascribed to a pacifist orientation that upheld an approach based on law. He believed that peace could only be guaranteed through the codification of international law, obligatory recourse to international arbitration, the creation of a League of Nations and the establishment of an International Court of Justice.

He became an active member of the pacifist movement in the early 1880s. At the time, he was working to create a Belgian section of the International Arbitration and Peace Association, which would be founded in 1889 under the name “Société Belge de l’Arbitrage et de la Paix”. He subsequently became an important figure in Belgian and international pacifism, in particular within the International Peace Bureau (IPB), where he served as president from 1907 until his death in 1943, and the Inter-Parliamentary Union, whose conferences he actively participated in after joining the Belgian senate in 1895.

On the home front, he worked to bring together Belgium’s pacifist societies, and in 1913, he was able to organise the first National Peace Congress in Brussels as well as set up a Permanent Delegation of Belgian Peace Societies.

The Socialist↑

Henri La Fontaine was in regular contact with the Belgian Labour Party (BWP/POB) from the time of its creation in 1885. His official affiliation, however, only dates back to 1894. Prior to this, his position oscillated between progressive liberal, as expressed through his becoming a member of the Liberal Association of Brussels in 1877, and socialist. The friendship he formed with Émile Vandervelde (1866-1938), the socialist leader, was a determining factor in his final orientation towards socialism.

Henri La Fontaine’s political career began in earnest in 1895 when he was elected to the senate, where he would continue to hold a seat until 1935, with the exception of two absences: one in 1898-1899, and the other in 1932-1935. He went on to serve as secretary and first vice president of the senate, and took part in the debates regarding the fight for universal suffrage, education, working conditions and international issues. On his arrival, he became a member of the Foreign Affairs Committee, and later served as its vice president and then president. As a prominent figure in the pacifist movement who was aware of the internationalist dimension of the socialist movement, he also encouraged the Workers’ Party of Belgium to open up to pacifist movements despite their differences.

He was active in the International Socialist Bureau, established at the headquarters of the POB. Before the First World War, he took part in the extraordinary meetings on the international situation, which studied a possible agreement to prevent the war. Henri La Fontaine wrote the resolution decreeing that in the case of the outbreak of war, the duty of the working class is to use all means to stop it quickly. As a delegate of the International Socialist Bureau, he also represented Belgium, with Émile Vandervelde, at the first Allied conference held in London in February 1915.

His idea of socialism is set out in a brochure entitled Le Collectivisme, which he published in 1897. He believed that the means of production belonged to everyone and expressed support for removing the intermediaries between producers and consumers. He also favoured close collaboration between manual and intellectual workers. His convictions would lead him to take an active role in the developments of the Maison du Peuple in Brussels and the operation of several cooperatives.

The First World War and the League of Nations↑

At the outbreak of the First World War, Henri La Fontaine did not give up the struggle for peace, and went into exile, first in London in September 1914, then in the United States of America in April 1915, in order to continue his propaganda work and attempt to unite pacifists. Until the end of 1918, he worked on plans for the post-war period and the reconstruction of Belgium. He was convinced that Belgium should play a bigger role in international politics, because of the damage caused by the war and the violation of its neutrality. He further developed his ideas on the world after the war and insisted that all nations should be represented at the peace congress that would end the conflict and determine the conditions of peace.

It was in the United States in 1916 that he published his major work, The Great Solution. Magnissima Charta. The Existing Elements of a Constitution of the United States of the World – a constitutional text intended to form the basis for the establishment of a global state responsible for ensuring peace around the world. In that book, Henri La Fontaine explained the need for a federal organization of the nations and for international courts that could use armed force to avoid the use of violence in case of international disagreements or to enforce their judgments.

At the end of the war, Henri La Fontaine was chosen as a technical advisor for the Peace Conference held in Paris in 1919. The conference resolved to create the League of Nations, at the assembly of which he was a Belgian representative in 1920 and 1921. During his time at the League of Nations, Henri La Fontaine focused mainly on two issues: the status of the International Court of Justice and international intellectual cooperation.

Although the League of Nations was the realization of the hopes of many pacifists, Henri La Fontaine was soon warning of the risk that continuing international tensions and the economic and financial crisis would culminate in a new conflict. He stressed the need to establish a new world order and advocated the introduction of an international jurisdiction to which states would be obliged to turn in case of conflict, with order assured by an international public force. In the 1930s, disappointed by the League of Nations’ inability to guarantee peace and by the rise of nationalism, Henri La Fontaine directed his message at the masses, whom he saw as the sole remaining hope. He continued to campaign until the end of his life for the establishment of an international code of law that would guarantee human rights and maintain world peace. His dreams were destroyed once again by the outbreak of the Second World War, the end of which he would not live to see.

Peace through Knowledge↑

Henri La Fontaine thought that different peoples’ ignorance of each other was an obstacle to sustainable peace. This idea underpinned the projects he developed with Paul Otlet in the spheres of bibliography, documentation and access to information. In 1895, the two men created the IIB, whose activities and developments gave rise to the Mundaneum. The IIB’s first mission was to establish the Universal Bibliographic Repertory, which was intended to bring together the bibliographical details of every publication in the world.

Paul Otlet and Henri La Fontaine later expanded their scope to cover not just books, but also other sources of information. Within the IIB, they created specialised sections that worked on a particular medium (e.g. the press, or posters) and collected countless documents. This expansion also resulted in the creation of the Union of International Associations in 1907 and the International Museum in 1910. These institutions were brought together at the Palais du Cinquantenaire in Brussels under the name of the “Palais Mondial” or “Mundaneum”, which was destined to be an international centre dedicated to sharing knowledge.

In 1934, the Belgian government decided to close the Mundaneum. However, it survived and, after moving several times within Brussels, was moved to Mons, where it has been housed since 1993.

Jacques Gillen, Mundaneum

Section Editor: Emmanuel Debruyne

Selected Bibliography

- Abs, Robert: Fontaine (Henri-Marie La), in: Académie royale des sciences, des lettres et des beaux-arts de Belgique (ed.): Biographie nationale, volume XXXVIII, Brussels 1973: Établissements Émile Bruylant, pp. 213-222.

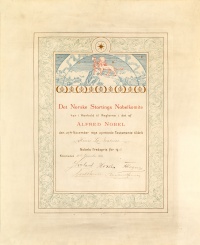

- Gillen, Jacques: Henri La Fontaine, Prix Nobel de la paix en 1913. Un Belge épris de justice, Brussels 2013: Racine.

- Hasquin, Hervé / Lecocq, Suzanne / Lefebvre, Daniel: Henri La Fontaine, prix Nobel de la paix 1854-1943: tracé(s) d'une vie, Mons 2002: Mundaneum.

- Lubelski-Bernard, Nadine: La Fontaine, Henri Marie, in: Josephson, Harold (ed.): Biographical dictionary of modern peace leaders, Westport 1985: Greenwood Press, pp. 538-539.