Military Career↑

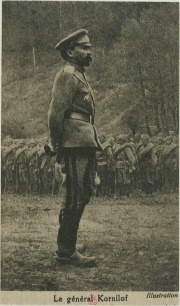

Lavr Kornilov (1870-1918) was a Siberian Cossack but entered the regular Russian army rather than the Cossack forces. During the First World War he rose to commander of the Petrograd Military District in March 1917, taking charge of the 8th Army for Russia’s offensive of June and July 1917. He was appointed commander of the southwestern front by new Prime Minister, Aleksandr Fedorovich Kerenskii (1881–1970), on 8 July (21 July) 1917. Mere ten days later, he received promotion to the army’s Commander-in-Chief.

Historians offer differing explanations for Kornilov’s meteoric rise. Leonid Strakhovsky argues that Kornilov earned a heroic reputation in the Imperial Army from events at Pzemysl. His unit attacked Przemysl in spring 1915, which contributed to the fall of the Austrian fortress despite Kornilov’s capture; he then dramatically escaped from prison camp in autumn 1916. His advances in the ultimately disastrous June 1917 offensive secured his ascent under the Provisional Government that ruled Russia following the toppling of the tsar in February.

Other historians, such as Alexander Rabinowitch, characterise Kornilov’s military record as undistinguished at best. The bulk of his division at Przemysl was annihilated when he disobeyed orders to withdraw, and his 8th Army was routed once German reinforcements arrived. The aura of bravery surrounding his prison escape was fostered by a Russian press that was given to hailing any small triumph in a militarily bleak period. Alternative explanations for his promotion include a lack of other choices and his appeal to both democratic and authoritarian sensibilities. His background as son of a smallholder and low-ranking officer, and the arrest of Alexandra Feodorovna, Empress consort of Russia (1872–1918) while he was commander of the Petrograd Military District, lent him a desirable democratic pedigree in the wake of the February Revolution. In his report to a meeting of the military high command on 16 July (29 July) 1917, Kornilov tempered criticism of permissive changes wrought by the Provisional Government and the powerful socialist council, the Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies, with some praise for political commissars and soldiers’ committees. Meanwhile his strongman reputation was enhanced by his order to fire on demonstrators protesting about government war aims in Petrograd in April 1917, which was countermanded by the Soviet, and his unsanctioned application of capital punishment to fleeing soldiers on the southwestern front. This raised his stock with influential advocates for order, including Boris Viktorovich Savinkov (1879–1925), a legendary figure of the Socialist Revolutionary terrorist organisation who became an army commissar and eventually Kerenskii’s deputy minister of war, and members of the liberal Kadet Party and industrialists with whom the Prime Minister wished to cooperate.

The "Kornilov Affair"↑

Background↑

In early July 1917, the deteriorating economy, social polarisation, and assignment of additional troops to the frontline brought soldiers, workers, anarchists, and Bolsheviks onto the streets in armed demonstrations. They demanded transfer of power from the Provisional Government to the Petrograd Soviet. The Soviet leaders declined power and the government directed short-lived repressions at Bolshevik organisations, but economic, social, and political breakdown continued. Discipline collapsed at the front, prices skyrocketed, the supply situation worsened, the Finns and Ukrainians made bids for autonomy, and there was a resurgence in peasant land seizures, worker militancy, and Bolshevik influence. By August, officers and business figures organised in groups such as the Society for the Economic Rehabilitation of Russia, the Officers’ Union and the Republican Centre, were demanding forceful measures to restore order and the fighting capacity of the army. These views were shared by representatives of Russia’s gentry, the Kadet Party and the Allies. Many in this spectrum of liberals, conservatives, and the extreme right concluded that authoritarian dictatorship was Russia’s lone hope and Kornilov might be their saviour.

Kornilov and Kerenskii↑

Upon his appointment as Commander-in-Chief, Kornilov stipulated he was responsible only to his conscience and the people. He demanded the dismissal of the democratically inclined General Vladimir Andreevich Cheremisov (1871-?), his replacement on the southwestern front. Kornilov also pushed for the reintroduction of capital punishment in the rear as well as at the front. On 3 August (16 August) 1917 he proposed prohibition of assemblies of frontline soldiers and reversed his earlier support for political commissars. Later he added provisions to place the railroads and factories engaged in defence work under martial law, thereby banning strikes and political meetings, imposing work quotas in many enterprises, and restoring the death penalty for civilians. Kerenskii agreed to Cheremisov’s reassignment - providing Kornilov pledged responsibility to the government - and was sympathetic to the other proposals. However, Kerenskii objected to Kornilov’s provocative tone.

Concerned about repercussions from the left, Kerenskii attempted to restore the political middle ground by assembling representatives from the military, business, trade unions, soviets, and local and central government at the Moscow State Conference from 12 to 14 August (25 to 27 August). This only underscored divisions in Russian society, as the conference opened with a Bolshevik-led strike. Kornilov’s appearance was greeted by a roaring ovation from half the delegates and hostile silence from the others. As Kerenskii wavered, Kornilov acted. On 6 August (19 August) he requested the Petrograd Military District be placed under his command in case of enemy assault. He also ordered Third Cavalry Corps troops closer to the capital to deal with any Bolshevik unrest. On 25 August (7 September), with German forces having taken Riga, he commanded divisions to proceed into Petrograd. He informed a former Provisional Government official that he required Kerenskii to proclaim martial law in the capital, place all military and civil authority in the hands of the Commander-in-Chief, and come to army headquarters in Mogilev to ensure his safety and discuss the formation of a new cabinet. Having verified Kornilov’s insistence that he come to Mogilev in an infamous teleprinter conversation on 26 August (8 September), Kerenskii denounced him as a traitor.

Response and Legacy↑

Kerenskii obtained unlimited emergency powers from the cabinet and telegrammed Kornilov for his resignation, ordering troop movements to halt. When this order was disregarded, the Soviet mobilised railwaymen to hold up the troops and disrupt communications among Kornilov’s supporters. Meanwhile in Petrograd, workers formed armed detachments of Red Guards, and soldiers and sailors occupied strategic positions and attacked suspected counterrevolutionary officers. There were few skirmishes, however. The Bolshevik riot that Kornilov’s forces were supposed to suppress failed to materialise. Agitators easily convinced his troops to capitulate, and Kornilov was arrested. The ultimate winners were the Bolsheviks who had helped organise resistance to Kornilov. They were prepared to lead armed workers and radicalised garrison soldiers against a government irrevocably discredited by suspicions of Prime Minister Kerenskii’s own counterrevolutionary intentions.

Following the Bolshevik revolution in October, Kornilov fled and gathered a Volunteer Army on Don Cossack territory to fight the Reds in the ensuing Civil War. He led White forces in the notorious Ice March, which saw atrocities committed against peasants reluctant to relinquish food and in reprisal for Red violence. Kornilov ultimately perished in a doomed siege of Bolshevik-held Ekaterinodar.

Assessments↑

Historians dispute whether Kornilov’s actions in August 1917 constituted a carefully planned coup, an effort by Kerenskii to manipulate the simple-minded general to strengthen his own power, or a botched attempt at cooperation in an authoritarian direction. Controversy surrounds the intentions of the protagonists, including the fate Kornilov had in store for Kerenskii at army headquarters, the extent to which they deceived or misunderstood each other, the involvement of Kornilov in various right-wing plots, and whether Kornilov was responding to or provoking revolt from the left. The picture is further complicated by the shadowy role of go-betweens and advisers and the unreliable evidence of those involved who sought to exculpate themselves from delivering Russia to the Bolsheviks. Also confounding the analysis of the situation are polemics by historians such as Strakhovsky, who claims Kerenskii concocted the plot from nothing; or Abraham Ascher, who blames rebellion by Kornilov for destroying a fragile political stability. Some historians have attempted to evaluate Kornilov more dispassionately: Harvey Asher concludes that he may have wished to act with the blessing of the government but was prepared to continue without it. Others have shifted the focus to the context in which Kornilov operated, including army disintegration, industrialist discontent, and the wartime erosion, localisation, and militarisation of state structures, which fostered the emergence of Russian "warlords."

Siobhan Peeling, University of Nottingham

Section Editors: Yulia Khmelevskaya; Katja Bruisch; Olga Nikonova; Oksana Nagornaja

Selected Bibliography

- Ascher, Abraham: The Kornilov affair, in: Russian Review 12/4, 1953, pp. 235-252.

- Asher, Harvey: The Kornilov affair. A reinterpretation, in: Russian Review 29/3, 1970, pp. 286-300.

- Katkov, George: Russia 1917, the Kornilov affair. Kerensky and the break-up of the Russian army, London; New York 1980: Longman.

- Munck, Jørgen Larsen: The Kornilov Revolt. A critical examination of sources and research, Aarhus 1987: Aarhus Univ. Press.

- Rabinowitch, Alexander: The Bolsheviks come to power. The revolution of 1917 in Petrograd, New York 1976: W. W. Norton.

- Sanborn, Joshua A.: The genesis of Russian warlordism. Violence and governance during the First World War and the Civil War, in: Contemporary European History 19/3, 2010, pp. 195-213.

- Strakhovsky, Leonid I.: Was there a Kornilov rebellion? A re-appraisal of the evidence, in: The Slavonic and East European Review 33/81, June 1, 1955, pp. 372-395.

- White, James D.: The Kornilov affair. A study in counter-revolution, in: Soviet Studies 20/2, Oktober 1, 1968, pp. 187-205.