Introduction: Organization and Tasks↑

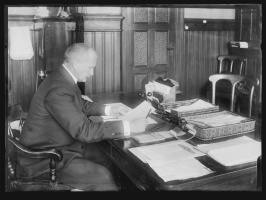

When the First World War broke out in 1914, the agencies charged with carrying out the collection of intelligence and counterintelligence were yet in their infancy. The Intelligence Office of the General Staff, manned by only two officers, collected information but had no operational capacity to investigate, conduct surveillance or apprehend suspects. Such tasks were the responsibility of the police, which had no centralized direction or coordination. Responsibility for counteracting the activities of foreign intelligence agencies fell to Opdagelsespolitiet, the detective departments of the local police forces, which became increasingly centralized under the Kristiania-branch and its entrepreneurial head Johan Søhr (1867-1949).[1]

The information flow increased significantly after the outbreak of war, as the Norwegian public came to treat anyone appearing to be foreign with suspicion. The majority of the cases reported to the police, however, were about Russians, East European Jews or Germans, reflecting a clear bias in the public’s perception. The heightened public awareness, coupled with several espionage cases uncovered in 1914 and 1915, led the Ministry of Justice to decide in summer 1915 that counterintelligence efforts should be coordinated under the leadership of the Kristiania Detective Department. However, outside the major cities the operational capacity was wholly dependent upon collaboration with the local police and the army. The Intelligence Office of the General Staff under Captain Trygve Graff-Wang (1875-1952) was upgraded but remained an organization for collecting and coordinating information with the police. Graff-Wang collaborated closely and shared information with his Danish counterpart, Captain Erik With (1869-1959), but no such cooperation seems to have existed with the Swedish General Staff.[2]

The Norwegian counterintelligence grew in size, capability and effectiveness throughout the war. In the first years, however, dissatisfaction arose from prosecutors’ hesitance to bring espionage cases to trial. Foreign agents were merely expelled, and the cases did not, as a rule, become public knowledge. As a result, foreign intelligence could operate virtually unrestricted. This only started to change from 1917 onwards. After the extradition of a Swede in German service, Baron Otto von Rosen (1884-1963), in the spring of 1917, the Norwegian police became aware that anthrax germs were among his seized possessions. And unlike in previous cases, the knowledge reached the public and sparked harsh criticism. Furthermore, it added to the building British pressure on Norwegian authorities to put an end to such activities.[3]

Russian Intelligence in Norway↑

Norway was concerned about foreign espionage even before the outbreak of war in 1914. Following the country’s independence from Sweden in 1905, these concerns were first and foremost aimed at Swedish citizens, but a deepening mistrust towards Imperial Russia due to its behaviour in Finland and a fear that it might wish to annex ice-free harbours in northern Norway meant that Norway increasingly also came to view Russia as a threat. The period 1910-14 saw a Russian spy scare when itinerant Russian saw-grinders started to appear in large numbers throughout the country. Fuelled in part by reports from Sweden, the Norwegian public suspected that the Russians were part of an extensive intelligence network, a fear that was fed by public statements from the General Staff and the Norwegian police that seemed to confirm the allegations, even though no evidence was ever produced to support these claims.

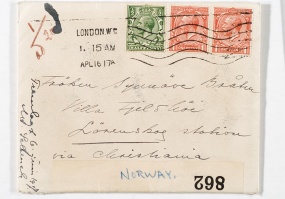

There is, however, ample evidence of Russian intelligence running covert mailing addresses for transmitting intelligence reports from continental Europe through Norway to avoid suspicion. One of these organisations, set up by the Russian military attaché, Lieutenant Colonel Piotr Assanovich (?-1915), was discovered in 1913. Among those who used this channel was the Russian agent in the Austro-Hungarian General Staff, Colonel Alfred Redl (1864-1913). Besides transmitting information, however, Russian intelligence put little emphasis on Norway itself, and the same can be said for British and German intelligence, who were mostly interested in mapping the Norwegian coast to prepare for the coming naval war in the North Sea.[4]

The Spy Act of 1914↑

Just days after the outbreak of war in August 1914, the Norwegian parliament passed the “Defence Secrets Act” or - as it became known - the “Spy Act”. Throughout the war, this law provided the main authorization for the police in matters of espionage. The law had been under development since late 1913 after an initiative from the General Staff, but the process was expedited after war broke out in the summer of 1914. The motivation behind the law was the volatile international situation in general, but especially the Russian threat, and it was largely modelled on a similar law passed in Sweden the previous year. The law criminalized all espionage activity on behalf of a foreign power on Norwegian soil, made military areas off-limits, and forbade the drawing of sketches and maps as well as photographing. The purpose was to calm the public’s fears that the government was unable to deal with the menace of foreign spies and to give the Norwegian police the necessary tools to counteract the subversive activities of foreign powers endangering Norway’s status as a neutral country.

A related problem was the large influx of foreigners to Norway, as the warring countries expelled thousands of aliens from their territories and thousands more chose to leave on their own account to seek refuge in neutral countries. At the same time, Norway’s ports were a transit area for everyone from deserters, wounded soldiers, and escaped prisoners of war to diplomats, journalists, and businessmen. As a small and homogenous country on the periphery of Europe, previous experience of such large-scale immigration was limited, and xenophobia was widespread.

In June 1915, an existing law on the control of aliens was amended, removing legal guardrails against the police expelling foreigners or monitoring their mail and telegram correspondence. Later further regulations followed, making it compulsory for all foreign citizens to register, authorizing the police to ban foreigners from residing in certain municipalities, and making passports mandatory.

German Intelligence in Norway↑

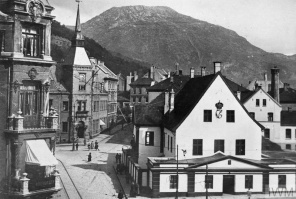

The only known German intelligence operations in Norway pre-1914 were mapping tours by German naval officers along the coastline. With the outbreak of war, however, the country suddenly became an interesting area for the Nachrichtenabteilung of the Admiralty Staff and the Abteilung IIIb of the General Staff, initially as a launchpad for sending German agents into Great Britain and providing convenient covert addresses for German agents in Britain.[5] Bergen in western Norway was the only Scandinavian port with regular passenger ship service to Great Britain, and one of the first agents sent through this route in early autumn 1914 was Carl Hans Lody (1877-1914), who was the first German spy executed in Great Britain. IIIb also established an intelligence base in Kristiania in the fall of 1914, but the local police soon detected the operation as the lead agent exposed himself by sending and receiving large amounts of mail.

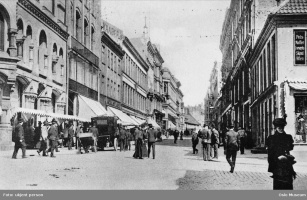

In early 1915, IIIb gave way to the N-Abteilung and pulled out of Norway altogether. In July 1915, the N-Abteilung established an intelligence post in Gothenburg - Zweigstelle Gothenburg, led by Lieutenant Edwin Nordmann (1874-?). This soon established substations in Kristiania, Bergen, Copenhagen, Malmö, and Stockholm. Over the following years, these posts sent a large number of agents into Great Britain, but the poor quality of the intelligence produced coupled with a very high discovery rate led to a change in German policy, putting more emphasis on establishing a greater presence in the neutral countries themselves. A contributing factor was the submarine war launched in February 1915, defining the waters surrounding the British Isles as a war zone, which prompted the N-Abteilung to set up further substations along the coast, so-called Schiffbefragungsdienst, for monitoring shipping movements. While the agents running substations in the major cities were mostly German nationals, the ship-watchers were generally Norwegians. The substation in Kristiania was given the additional tasks of observing British intelligence, monitoring expatriate Germans, investigating companies trading with the enemy, and recruiting spies with ostensible legitimate reasons for entering Great Britain. The most important substation was “Organisation Bergen”, with its crucial geopolitical position on the Norwegian west coast. The importance is reflected in the frequent rotation of the leadership to avoid discovery by the Norwegian counterintelligence.

“Organisation Kristiania” was discovered by the police in 1916, and the German agents expelled from Norway. Moreover, while the station was quickly re-established with new personnel, it took but six months for the Norwegian police to yet again arrest and expel the leadership.[6] Norway’s rather lax approach to foreign espionage, however, was to change with the reopening of German submarine warfare in February 1917. Within six months, the Germans had sunk some 300 Norwegian ships, killing close to 450 sailors, and several ship captains reported that the German submarines appeared to have advance knowledge of their course. Until this point, all foreign agents had been treated equally, regardless of their country of origin, but the submarine war turned public opinion against Germany and paved the way for stricter measures against German spies. When “Organisation Bergen” was finally uncovered in 1917, it stirred up a media frenzy, and while the German agents leading the operations managed to flee, ten local helpers were caught and tried. N-Abteilung soon worked to re-establish their stations in both Bergen and Kristiania. Due to lax security measures another round of arrests took place in the spring of 1917. This time, the Germans agents were also arrested and tried, making them the first foreign citizens imprisoned for espionage in Norway.[7]

In 1916, N-Abteilung had also established a new department, NIV, to run sabotage operations. Directed from Stockholm, most of the personnel were Finnish expatriates. The operation was uncovered in June 1917, when Walther von Gerich (1881-1939) was arrested in Kristiania with a large cache of explosives. Von Gerich, who travelled as a German diplomatic courier under the alias Baron Walther von Rautenfels, transported the explosives in sealed diplomatic bags. The Norwegians, however, had been notified in advance by MI6, and soon after his arrival in Kristiania, von Gerich and his helpers, who were mostly Finnish or of Finnish-Swedish descent, were apprehended. The police also located nearly 1,000 kilos of explosives in local storage. Due to diplomatic immunity, the Norwegian government had to release von Gerich, albeit along with a sharply worded protest. His accomplices were tried in a public trial later in 1917 and given severe sentences. This case also alerted the Swedish police as well as the press to the Germans’ sabotage operations in Stockholm, and the NIV office was soon forced to shut down.

Throughout the war, but increasingly from the end of 1917, the losses of German personnel in Norway were significant, although not crippling. A case in point is that the new leader of the Kristiania substation, who seems to have produced somewhat valuable reports throughout 1918, was never identified by either Norwegian police or British intelligence.[8]

British Intelligence in Norway↑

The aims of British intelligence in Norway were constant and twofold throughout the war. Firstly, to disrupt German intelligence operations in Norway, especially hindering their agents and information from moving in and out of the British Isles, as well as monitoring local trade and composing a “blacklist” of Norwegian companies and businessmen trading with Germany. Secondly, military intelligence, MI6, wanted to collect naval intelligence, especially on German and neutral ship movements.

At the outbreak of war, MI6, like their German counterpart, did not have a presence in Norway. In late autumn of 1914, it therefore recruited the naval officer Frank Noel Stagg (1884-1956) and assigned him to run its Scandinavian operations. His most important task was to infiltrate northern Germany and gather information about the Kriegsmarine; operations in Norway were secondary. The first MI6 operation in Norway, therefore, was a coastal ship-watching network run by the artillery officer Richard Carlyle Holme (1877-1972), who was sent to Kristiania on a fictitious sick leave in October 1914. The network soon encompassed as many as twenty Norwegians and expatriate Brits, but came to the attention of the Norwegian police, not least because several of the recruits were ex-criminals and known fortune seekers. The British officer was arrested in late 1915, whereupon he immediately confessed. As in the German cases, the British citizens were expelled, and their Norwegian accomplices let off with a warning.

At this point, Stagg had to be pulled out of Denmark after German complaints, and in the following year, he focused on the Norwegian operations, where he travelled throughout the country using an American passport. While in Norway, he developed several productive liaisons, particularly with the police and the navy, which gained him direct access to reports from the Norwegian navy’s coastal observation stations and radio listening posts. The British Admiralty went so far as to send technicians to a Norwegian base to improve its listening technology. The ties between British and Norwegian officials were unofficial and based on personal connections, and it is difficult to determine from available sources if the Norwegian government sanctioned them. It is, however, more likely than not that they did.

British intelligence operations were discreet and consisted mainly of collecting information from open sources and informal contacts, rather than outright espionage. In 1917, only ten British agents were listed as active in Norway and in several cases, MI6 instead hired private detectives to collect information on people and places of special interest. MI6’s success in monitoring and banning companies that traded with Germany, where they collaborated closely with the Norwegian Ship Owners Association among others, seems to have been considerable, especially measured against the delicate balancing act of maintaining accord with governments in the countries where these activities took place. That said, this was in large measure due to its more limited aims when compared to the Germans and its success in forging a collaborative relationship with Norwegian agencies and individuals.[9] In some cases, British agents were requested to lower their profile, but no Brits were ever prosecuted.[10]

The Spy-scare of 1917, and the End of the Spy War in 1918↑

More than any other year of the war, 1917 was characterized by “spy mania”, when real and imagined plots of sabotage and espionage dominated the public discourse. There were three reasons for this: first, German submarine warfare provoked anti-German sentiment, as Norwegian ships were increasingly targeted. Second, the image of the German spy threat was enhanced by several high-profile public court cases against German agents and their Norwegian accomplices. Finally, the Russian Revolution caused a widespread fear of an imminent world revolution spreading to Norway, especially among the bourgeoisie.

The Norwegian authorities received an increasing amount of reports of alleged espionage and subversive activities, as anyone who seemed even remotely “foreign” – i.e. German, Jewish, or Slavic – was treated with suspicion by the public. The catalyst was the public outrage, whipped up to a frenzy by Norwegian media during prominent court cases of espionage in the spring and summer of 1917, coupled with a renewed fear that neutrality was threatened as the continental war shifted with the German spring offensive in 1918. The added element of the Bolshevik threat was felt even more so, as the revolutionary faction within the Norwegian Labour Party acceded to power at the party’s national convention, and thus further stirred the public imagination.[11] Accordingly, the trifecta imagery of German = Jew = spy was seamlessly replaced by Bolshevik = Jew = spy.[12]

Towards the end of the war, German intelligence kept a low profile, and larger operations such as sabotage were generally avoided. Instead, the focus was on running mundane day-to-day intelligence gathering. The coastal Schiffbefragungsdienst was still operative, but the recruitment and dispatch of agents to Great Britain was not prioritized. N-Abteilung continued to send in agents to Norway, and several were caught and tried, but the court cases no longer produced a media storm. If one considers the lowered ambitions, these operations went quite well, as significant amounts of information were sent back to Germany.

From 1918 onwards, both the German and British intelligence agencies turned their interest towards Russia and Bolshevik activity in Europe, and Norway took on a new role as a gateway to the east. A case in point is the arrest of a Norwegian-Dutch businessman sent by Zweigstelle Gothenburg to Bergen in April 1918, equipped with a detailed questionnaire concerning communist activities. As for the Norwegian counterintelligence, most of those who had been assigned to counterintelligence were redeployed to their pre-war assignments or put to work investigating communists after the armistice on 11 November 1918.[13]

Conclusion↑

The intelligence war in Norway had no clear victors. If we judge the success of the various agencies against their aims, Germany was the loser, as Norway was supposed to be a bridgehead to Great Britain. Even if several agents were sent into Great Britain, little information of any value was gained. On balance, German operations in Norway were counter-productive, especially as they contributed to turning public opinion decisively against Germany. The British, on the other hand, succeeded in disrupting the German operations and gained the cooperation of the Norwegians, but these advances were rather a testament to their low ambitions than skills or ingenuity.

What about Norwegian counterintelligence? The increased attention paid to Norwegian territory by the warring powers meant that government had to strike a delicate balance to protect its neutrality. Publicly, the Norwegian government followed a dual approach of state neutrality while allowing the private sector to act in cohort with Great Britain, a policy that has been dubbed “the neutral ally”.[14] However, the major triumphs of the Norwegian counterintelligence were based on information from the British, and in reality, the Norwegian counterintelligence functioned as a subsidiary of MI6. Even if the Norwegians were generally unsuccessful in preventing Germany or Great Britain from operating on its territory, the close cooperation with MI6 provided a backchannel that was utilized to great effect in promoting understanding for Norway in British government circles.[15]

Nik. Brandal, Bjørknes University College

Ola Teige, Volda University College

Section Editor: Eirik Brazier

Notes

- ↑ Brandal, Nik / Teige, Ola: The Secret Battlefield. Intelligence and Counter-intelligence in Scandinavia during the First World War, in: Ahnlund, Claes (ed.): Scandinavia in the First World War. Studies in the War Experience of the Northern Neutrals, Lund 2012, pp. 85-88.

- ↑ Berg, Roald: Norsk utenrikspolitisk historie, II Norge på egen hånd 1905-1920 [History of Norway’s Foreign relations, II Norway on Its Own 1905-1920], Oslo 1995, pp. 182-215; Kjeldstadli, Knut / Myhre, Jan Eivind / Niemi, Einar: Norsk innvandringshistorie, II I nasjonalstatens tid 1814-1940 [Norwegian Emigration History, II In the Time of the Nation State 1814-1940], Oslo 2003, pp. 376-82.

- ↑ Søhr, Joh.: Spioner og bomber. Fra opdagelsespolitiets arbeide under verdenskrigen [Spies and Bombs. From the Work of the Detective Police during the War], Oslo 1938, pp. 24-62, 99-116 and 148-151; Olin, K.-G.: Tärningkast på liv och död [Rolling of the Dice for Life or Death], Jakobstad 2009, pp. 202-32.

- ↑ Greve, Tim: Spionjakt i Norge. Norsk overvåkningstjeneste i tiden før 1940 [Spy Hunting in Norway. Norwegian Surveillance before 1940], Oslo 1982, pp. 27-59 and 72-88.

- ↑ Boghardt, Thomas: Spies of the Kaiser. German Covert Operations in Great Britain during the First World War Era, London 2004, pp. 6-20 and 80-88.

- ↑ Pöhlmann, Markus: German Intelligence at War 1914-1918, in: Journal of Intelligence History 5/2 (2005), pp. 23-54; Boghardt, Kaiser 2004, pp. 12-20, 80-94; Greve, Spy 1982, pp. 31-69.

- ↑ Riste, Olav: The Neutral Ally. Norway’s Relations with Belligerent Powers in the First World War, Oslo 1965, pp. 126-191.

- ↑ Boghardt, Kaiser 2004, pp. 15-16, 120-140, 158 and 170; Brandal / Teige, Secret 2012, pp. 94-102.

- ↑ Jeffery, Keith: MI6. The History of the Secret Intelligence Service 1909-1949, London 2010, pp. 87-89 and 94-97; Judd, Alan: The Quest for C. Sir Mansfield Cumming and the Founding of the British Secret Service, London 1999, p. 318.

- ↑ Brandal / Teige, Secret 2012, pp. 99-95.

- ↑ Sørensen, Øystein / Brandal Nik: Det norske demokratiet og dets fiender 1918-2018 [The Norwegian Democracy and Its Enemies], Oslo 2018, pp. 21-23.

- ↑ Brandal / Teige, Secret 2012, pp. 102-103.

- ↑ Søhr, Spies 1938, pp. 130-131; Jeffery, MI6 2010, pp. 87-109, 134-138, 172-178, 193.

- ↑ Riste, Neutral 1965.

- ↑ Cf. Brandal, Nikolai / Brazier, Eirik / Teige: Den mislykkede spionen. Fortellingen om kunstneren, journalisten og landssvikeren Alfred Hagn, Oslo 2010, pp. 173-178.

Selected Bibliography

- Boghardt, Thomas: Spies of the Kaiser. German covert operations in Great Britain during the First World War era, Baskingstoke 2004: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Brandal, Nik. / Teige, Ola: The secret battlefield. Intelligence and counter-intelligence in Scandinavia during the First World War, in: Ahlund, Claes (ed.): Scandinavia in the First World War. Studies in the war experience of the northern neutrals, Lund 2012: Nordic Academic Press, pp. 85-108.

- Greve, Tim: Spionjakt i Norge. Norsk overvåkingstjeneste o tiden før 1940 (Spy hunting in Norway. Norwegian surveillance before 1940), Oslo 1982: H. Aschehoug.

- Jeffery, Keith: MI6. The history of the Secret Intelligence Service 1909-1949, London 2010: Bloomsbury.

- Judd, Alan: The quest for C. Mansfield Cumming and the founding of the British secret service, London 2000: HarperCollins.

- Pöhlmann, Markus: German intelligence at war, in: Journal of Intelligence History 5/2, 2005, pp. 25-54.

- Søhr, Joh: Spioner og bomber. Fra opdagelsespolitiets arbeide under verdenskrigen (Spies and bombs. The work of the Norwegian Police Security Service during the world war), Oslo 1938: Johan Grundt Tanum.