Early Years↑

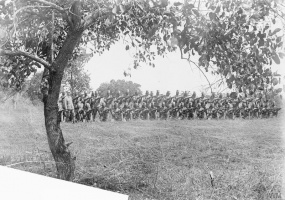

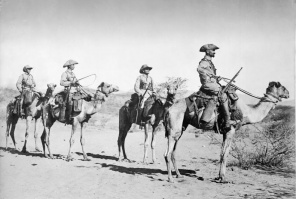

Bayume Mohamed Husen (1904-1944) was the son of a Sudanese professional soldier in the German colonial army of German East Africa, the “Schutztruppe”, and a local woman. Shortly after the outbreak of World War I, at the age of ten, Husen joined the German colonial army as a child soldier. The main tasks of child soldiers were carrying guns to and from the front line and acting as signalers in the field, operating heliographs.[1] Although they were euphemistically called signal troop apprentices (“Signalschüler”), their assignments were very dangerous. According to his own testimony, Husen was wounded in October 1917 at Mahiwa in one of the bloodiest battles on African soil and imprisoned by the British for an unknown period of time. His father was killed in action.

New Beginnings in Berlin↑

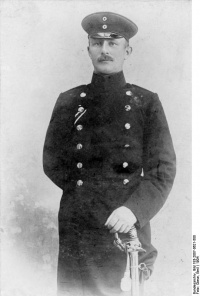

When German East Africa became British Tanganyika, Husen, like many other African veterans, failed to establish a livelihood. He signed on as a steward on several German ships, but finally migrated to Berlin in 1929. When he tried to collect his outstanding service pay, he was told that the fund had already been closed. Through his contacts with former German colonial officers, he found work as an “exotic” waiter at “Haus Vaterland” where he worked for five years at the “Wild West Bar”. At the same time, he was employed as a Kiswahili teacher at Berlin University, a job which he held for ten years. During his university employment, he also served as a language informant for several German scholars. Husen mainly taught future colonial officers and thus took an active part in the colonial revisionist movement, which advocated and worked for the retrieval of the lost colonies. During the 1930s, Husen was the token “devoted former askari”, as the African soldiers of German East Africa were called, at innumerable events in the revisionist scene, which offered a home for him. His role was to demonstrate to the general public that the askari had been loyal to their German officers until the end of the war and that the former colonial subjects longed for the return of the German colonial masters. He seems – as several photographs show – to have done so with a certain pride.

From 1934 on, he worked as an actor in more than twenty films. His first role was in the colonial revisionist movie “Die Reiter von Deutsch-Ostafrika” (The Troopers of German East Africa) where he re-enacted his real life role as a child soldier, although he was already thirty years old. He was one of few actors of color who had speaking parts in several movies. Husen even had his own autograph card made, which depicted him in his (film) uniform and identified him as former askari in the “Schutztruppe” on the reverse.

Family Life↑

In 1932, Husen dated two German women who simultaneously became pregnant with his first two children. He married one of them, Maria Schwandner (1910-?), in 1933, three days before the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei came to power under Adolf Hitler (1889-1945). His sons Heinz Bodo (1933-1945) and Ahmed Adam (1933-ca. 1938) were born within six weeks of each other. Heinz Bodo, his illegitimate son, seems to have been adopted by Husen and his wife and stayed with the family until his death in 1945.[2] A girl, Annemarie (1936-before 1940), was born in 1936 as the family were struggling to make ends meet. Husen was lucky to be employed most of the time, but his excessive lifestyle and affairs made it difficult for his wife to support the family. Two of his children died before and shortly after the outbreak of World War II.

Like many migrants from former German colonies, Husen had been given a passport with the endorsement "Deutscher Schutzbefohlener“, which was not equivalent to full citizenship.[3] After the war and more so after Hitler's rise to power, Africans from the former colonies were regarded as nationals of the states that had succeeded Germany as colonial powers. Most of the Africans in Germany, Black Germans and their family members had to exchange their papers for alien passports, which had to be renewed every year. Failing to do so in time, Husen and his wife were convicted of passport fraud.

Husen and the German Authorities↑

Although Husen never applied for German citizenship, all evidence points to him identifying as German. He was constantly in dispute with the German authorities, not only over financial support, but also over his recognition as a World War I combatant. He saw himself as entitled to receive the Medal of Honor (“Frontkämpferabzeichen”), which could be awarded to front line veterans, and applied for it several times. With his applications, he initiated discussions amongst several administrative bodies about whether the medal should be awarded to non-white combatants. The authorities even asked for advice from Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck (1870-1964), the former commander of the East African forces, who had always presented himself as a special friend of the askari. The latter took the view that African combatants should not have any claim to the decoration, and the authorities finally decided that the medal should be reserved for white combatants. It is a demonstration of Husen’s agency that he apparently bought himself a medal in a military supplies shop and pinned it to the uniform he wore at revisionist events. Photographs show him wearing it proudly.

In 1939, shortly after the British and French declaration of war against Germany, Husen asked to be accepted in the Wehrmacht, but his admission was denied.

In 1941, Husen was denounced to the Nazi authorities and accused of miscegenation. As he was a well-known figure with the authorities and had unwaveringly refused to comply with the image of the grateful and subservient subject, fighting for his rights instead, there was no one at the university or within the colonial revanchist movement who came to his support.

Husen was transferred to Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp without trial in September 1941. He succeeded at surviving the inhumane living conditions in the camp for three years, but finally died on 24 November 1944.

In September 2007, Mohamed Husen became the first African to be given a memorial as a victim of Nazi terror. A “Stolperstein” – a bronze “stumbling block” – was set in the ground in front of his last address in Berlin.

Marianne Bechhaus-Gerst, Universität zu Köln

Section Editor: Michelle Moyd

Notes

- ↑ Heliographs were wireless telegraphs which signaled in Morse code using flashes of sunlight reflected by a mirror. The flashes were produced by moving the mirror in different directions or by interrupting the beam with a screen. In the 19th and early 20th century, heliographs were used in the military for long distance communication in the field.

- ↑ “Illegitimate” is here used to indicate the status under the law of the period.

- ↑ “Schutzbefohlener” is a euphemistic German term for “colonial subject”.

Selected Bibliography

- Bechhaus-Gerst, Marianne: Treu bis in den Tod. Von Deutsch-Ostafrika nach Sachsenhausen. Eine Lebensgeschichte, Berlin 2007: Links.

- Bechhaus-Gerst, Marianne / Zeller, Joachim (eds.): Deutschland postkolonial? Die Gegenwart der imperialen Vergangenheit, Berlin 2018: Metropol.

- Michels, Stefanie: Schwarze deutsche Kolonialsoldaten. Mehrdeutige Repräsentationsräume und früher Kosmopolitismus in Afrika, Bielefeld 2009: Transcript.

- Morlang, Thomas: Askari und Fitafita. 'Farbige' Söldner in den deutschen Kolonien, Berlin 2008: Ch. Links Verlag.

- Moyd, Michelle: Violent intermediaries. African soldiers, conquest, and everyday colonialism in German East Africa, Athens 2014: Ohio University Press.