Early Life and Career↑

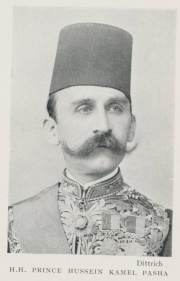

The second son of the Egyptian Khedive Isma’il the Magnificent (1830-1895), Husayn Kamil (1853-1917) was born in Egypt and received an early education there, later moving to Paris to complete his studies. He returned to Egypt in 1869, where he began serving in a number of high-level administrative positions in his father’s government. These included appointments as minister of education, public works, interior, war, and finance.

During this period, the question of who was to succeed Isma’il on the Egyptian throne was a subject of struggle and speculation. Isma’il obtained a decree from the Ottoman sultan altering the order of succession in Egypt and diverting it to his sons, in order of primogeniture. Afterwards, Isma'il appointed his three eldest sons – Tawfiq, Husayn, and Hassan, in order of seniority – to high government posts. But it was an open secret that Husayn was Isma’il’s favorite. However, just as Isma’il prepared to make a move against Tawfiq and set Husayn up as his successor, British General Edward Stanton (1827-1907) intervened and secured Tawfiq’s safety.

The British later deposed Isma’il in favor of Tawfiq in 1879, and Husayn again departed Egypt for Paris, which marked the start of a long period of isolation from Egyptian politics. Husayn returned to Egypt when his nephew, ‘Abbas Hilmi II (1874-1944), succeeded to the throne in 1892, but he remained aloof from Egyptian politics and devoted himself entirely to the promotion of agriculture and the exploitation of his estates in Upper and Lower Egypt.

Wartime Sultan of Egypt↑

The outbreak of the war in August 1914 catalyzed a shift in Egypt’s political situation, with Great Britain replacing the Ottoman Empire as the legal sovereign in Egypt under a “protectorate” that left the existing government in the country relatively intact. At the time, ‘Abbas Hilmi II was away on his summer vacation in Istanbul, working to strengthen relations between himself and the Ottoman government. For the next few months, the British denied his repeated requests to return to Egypt.

Accession to the Throne↑

Meanwhile, the British worked to secure Prince Husayn Kamil’s accession to the throne. Husayn initially refused the offer, voicing three concerns: that the British might not win the war, that even if the British did win, they would not grant Egypt independence, and that ordinary Egyptians would view a war against the Ottoman sultan with hostility. The prince may also have been hesitant due to pressure from his wife and his son, Kamal al-Din Husayn (1874-1932), who was married to the sister of ‘Abbas Hilmi II (see below). But Husayn soon changed his mind, saying that he would accept the offer on the condition that he rule Egypt as king. He was told this would be impossible in the context of a British protectorate, where he would technically be subordinate to the British king, but was instead offered the title of sultan. Husayn accepted the offer, and the British residency quickly issued orders to him not to make any decision without their agreement, and, as part of his promotion to sultan, they raised Husayn’s salary from 100,000 Egyptian pounds to 150,000 Egyptian pounds annually.

British authorities spent the next six weeks laying the groundwork for the announcement. Throughout November 1914, reports were issued in the press – then under heavy British censorship – familiarizing their readership with Husayn’s biography and his various accomplishments. On 2 November 1914, British military authorities declared martial law in Egypt, and five days later, promised to undertake the defense of Egypt during the war. On 18 December 1914, the British foreign secretary gave official notice that Ottoman suzerainty over Egypt was terminated, and announced Husayn Kamil as sultan of Egypt.

Assassination Attempts↑

Despite British attempts to ingratiate Husayn Kamil with the Egyptian people, nationalist agitation against the sultan began almost immediately. By the end of December 1914, British military authorities had arrested nationalist activists and charged them with distributing pamphlets inciting rebellion against the protectorate and the sultan. In February 1915, a group of law students boycotted their scheduled meeting with the sultan, registering their displeasure in silent protest.

Popular antipathy toward the sultan reached its apotheosis with two separate assassination attempts in 1915, both of which failed. The first attempt took place on 9 April 1915, when a nationalist sympathizer attempted to shoot the sultan as he travelled through the streets of Cairo in his carriage. The attempt was foiled by the sultan’s guards, and the assailant was sentenced to death. The second attempt happened on 9 July 1915, as the sultan was on his way to join in at Friday prayers in Alexandria. As the sultan’s carriage proceeded to the mosque, a bomb was thrown from a third-floor window above, where it remained undetonated until after the carriage had driven by. Police later discovered the smoldering bomb and began an investigation that tied the ill-fated attack to a secret society – one of the many that had sprung up in Egypt since the outbreak of the war.

De-Ottomanization and British Military Rule↑

The Egyptian council of ministers met for the first time under Sultan Husayn on 21 December 1914, and quickly worked to sever Egypt’s remaining ties with the Ottoman Empire. They eliminated the office of the qadi of Egypt, which had previously been an Ottoman appointment, and issued an order to promote an Egyptian as president of the Egyptian Supreme Court – a position previously held by a Turk. Finally, they issued an order to say the Friday prayers in the name of Sultan Husayn, rather than the Ottoman sultan.

Sultan Husayn was generally content to allow British military authorities to govern Egypt as they saw fit under martial law. The meeting of the Egyptian legislative council had been delayed in October 1914, and the British continued to delay it five more times throughout 1915, before finally delaying it indefinitely on 27 October 1915. In January 1916, the sultan’s government collaborated with British military authorities to call up the reserve forces of the Egyptian army to assist with the logistics of defending Egypt from a second Ottoman attack on the Suez Canal. These actions contributed to a general feeling that the sultan was a British puppet on the throne.

Death and Succession↑

Sultan Husayn Kamil died on 9 October 1917, and was buried in a large ceremony at al-Rifa‘i mosque in Cairo. His half-brother, Ahmed Fu’ad Pasha (1868-1936) succeeded him. Many sources, including the famous novel Palace Walk by Najib Mahfouz (1911-2006), claim that Fu’ad was only chosen after the throne was refused by Husayn Kamil’s son, Prince Kamal al-Din Husayn – who they wrongly assert was next in the official order of succession. This belief that the prince refused the throne has persisted, and has led historians to speculate whether his refusal was based on nationalistic sympathies, pressure from his wife, or a personal preference for a life of adventure over the life of a statesman.

In fact, Sultan Husayn had never established an official order of succession with British authorities, who preferred to leave the question open. On 21 September 1917, three weeks before Husayn’s death, the British had already chosen Fu’ad as his successor, seeing in him another pliable monarch to occupy the throne during British military rule.

Kyle J. Anderson, SUNY Old Westbury

Section Editor: Abdul Rahim Abu-Husayn

Selected Bibliography

- A veteran diplomat; New York Times: New ruler of Egypt is a dancing sultan (in English), in: New York Times, 27 December 1914, pp. p. 6.

- Kilani, Muhammad Sayyid: Al-Sultan Husayn Kamil. Fatra Mudhlima fi Tarikh Misr (Sultan Husayn Kamil. A dark period in the history of Egypt), Cairo 1963: Dar al-Qawmiyya al-'Arabiyya lil-Tiba'a wa al-Nashr.

- New York Times: New ruler of Egypt is Prince Hussein (in English), in: New York Times, 19 December 1914.

- Salim, Latifah Muhammad: Misr fi al-harb al-'alamiyah al-ula. 1914-1918 (Egypt in the First World War, 1914-1918), al-Qahirah 1984: al-hay'ah al-misriyah al-'ammah lil-kitab.