Introduction↑

Different levels of national self-identification and political aspirations existed among the different ethnic groups living in the East Central European peripheries of the multinational empires. National activists (among them teachers, clergymen, and journalists) attempted to instil a sense of national identity among those segments of the population they considered part of their nation. But many members of the lower classes – especially the peasantry – remained indifferent to these efforts and continued to identify themselves in religious and regional terms. The problem of national identity and aspirations was particularly troublesome for the numerous Jewish populations of the region. German and Russian authorities conducted a policy of unification of their borderlands with the rest of their territories. The existing political regime, even in Russia, was allowed after 1906 to form political parties and participate in parliamentary activity.

The end of World War I saw the emergence of independent states in the former imperial peripheries of East Central Europe. The process of establishing, organizing, and consolidating these states started in 1916 with the Act of 5 November, which envisioned the creation of a semi-independent Polish State, continued under German tutelage with the signing of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in early 1918. This process changed course significantly with the German defeat as the consolidation of the new states now depended on the course of the Polish-Soviet War and the support of the Western Entente. The Riga Peace Treaty, signed in March 1921, consolidated the territories of the new states.

Poland↑

Despite the fact that Poland had vanished from the political map of Europe at the end of the 18th century, Poles remained politically active in the frameworks given by multinational empires in East Central Europe. Before 1914, almost all Polish parties, with the exception of radical social democrats in Russian Poland (SDKPiL), stressed the necessity of national solidarity, demanded an improvement in the position of Poles within existing states, and more or less openly declared themselves in favour of re-establishing an independent Poland.

The National Democrats, popular especially among the middle class, endeavoured to mobilise the lower classes of Polish society (peasants, workers) under a national solidarity principle and to strengthen their national identity. The Polish Socialist Party (PPS) combined social postulates with the idea of regaining their own statehood. Peasants, who gradually emancipated themselves from the traditional patronage of landowners and the Catholic clergy, apart from demanding land reform and a more even distribution of public burdens, acknowledged the necessity of the national cause. Conservatives and liberals lost momentum and influence in favour of these more radical and democratic trends in the political scene.

Polish politicians took an active part in the political life of their states by trying to defend their national rights in the central and regional parliaments (the Prussian Landtag and the Sejm Krajowy in Lwów/Lemberg). Due to the small number of Polish deputies (a dozen or more in the German Reichstag and the Russian Duma), their influence on the state politics remained very limited.[1] The strength the Polish deputies enjoyed in the Austrian Reichsrat was due to their attachment to the pro-government fractions. Many Polish conservatives attained the highest state positions, such as prime minister, minister of finance, and minister of foreign affairs.[2] Nevertheless, Poles’ parliamentary activity prior to 1914, with the cooperation of the Polish press and different social organisations, was more effective in mobilising Polish society and maintaining a national identity than in gaining real national concession from the central governments.

From the very beginning of the war, Polish public opinion and parties were divided between pro-Central Powers and pro-Entente options. The roles of coordination centres were assumed by the Supreme National Committee (Naczelny Komitet Narodowy) in Cracow and the Polish National Committee (Polski Komitet Narodowy) in Warsaw, which, after 1915, was relocated to Petrograd. In particular, during the second phase of the war, the role of the unofficial, exiled government in Paris, the Polish National Committee (Polski Komitet Narodowy), became crucial for the Polish cause.[3]

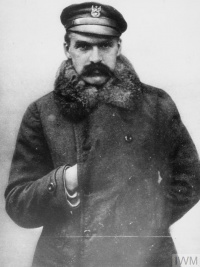

The occupation of the whole of Russian Poland in late summer 1915, and the declaration of the rebuilding of the Polish Kingdom announced by both of the Central Powers’ emperors in November 1916, dramatically changed this situation. Polish society in former Russian Poland was divided into the so-called “activists” (aktywiści), who were ready to cooperate with occupants under the condition of concessions to the Polish cause, and the so-called “passivists” (pasywiści), who distanced themselves from the new rulers. In December 1915, Józef Piłsudski (1867-1935) decided to establish his political agenda, named the Central National Committee (Centralny Komitet Narodowy), in occupied Russian Poland. But only a few leftist parties were represented there.[4] Conservatives and national democrats bided their time and observed the developments on the fronts, establishing the Inter-Party Political Circle (Międzypartyjne Koło Polityczne) in October 1915.[5] Gradually, after the Act of 5 November and, later, the fall of tsarism in Russia, conservatives became more willing to cooperate with the Central Powers. These politicians were nominated to the Provisional State Council (Tymczasowa Rada Stanu) in January 1917 and the Regency Council (Rada Regencyjna) in September 1917. Both bodies remained almost powerless.

At the beginning of the First World War, no Poles could even imagine that war would take a course so favorable to Polish national aspirations. As a result of this conflict, the three regimes which had partitioned Poland at the very end of 18th century collapsed, dissolved, and ceased to exist. This paved the way for a totally independent and united Poland. In the summer of 1914, one could only dream of an autonomous and united Poland within Russia or Austria-Hungary. In the first two years of the war, Poles tried to unite all Polish territories under Austro-Hungarian or Russian authority.

The political situation in Poland stabilised in January 1919. The Regency Council dissolved in November 1918, leading Piłsudski to became the provisional head of the new state. As a former collaborator of the Central Powers, Piłsudski was treated with distrust in London and Paris, and so Ignacy Paderewski (1860-1941) was nominated, who was well-known by the Western allies, to be the new Polish prime minister. This decision helped secure the international recognition of the authorities in Warsaw, a crucial step before the beginning of the Paris Peace Conference. At the end of January 1919, a first parliamentary election took place in the areas controlled by the Polish political institution. Territories which remained outside the control of Polish authority (Wielkopolska/Great Poland region, Pomerania, East Galicia), but were regarded as Polish, were represented in the new parliament by deputies elected to the Austrian and German parliament bodies before 1914. The main task of this constituent assembly (Sejm Ustawodawczy) was to work out a constitution, which would take effect in March 1921. The outcome of this election confirmed the radicalization of the Polish public opinion: the parliament was dominated by National Democrats, socialists, and peasant politicians.

The gradually changing political atmosphere, favourable to the idea of the rebuilding of the Polish state, opened a discussion regarding the borders of the future state. For many Poles, the only acceptable border was the one prior to 1772, before the first partition of the First Republic. This standpoint did not, however, take into account the fact of national emancipation and the political aspiration of the nations located between the Polish and Russian ethnic territories. Nor did it take into account the fact that many areas of the First Polish Republic had lost their Polish character.

Two conceptions of international order in East Central Europe were under discussion: the first one, called “federalist”, was promoted by Piłsudski. It assumed the building of a federation of nations living between the Baltic and Black seas (so-called Międzymorze, “inter-seas region”). This referred to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth before 1772 and, more broadly, to the period in the 16th century when many countries of that region had been ruled by the Jagiellonian dynasty. The realization of this project would grant the nations of the region freedom from Russian and/or German claims of domination. Piłsudski was willing to accept smaller territorial acquisitions in the east, which would establish a chain of national states politically and militarily linked to (and to some extent dependent upon) Poland and separate from Bolshevik Russia. For that reason, Poland supported – in vain – the establishment of a Ukrainian state on the terrain east of the Zbrucz River.[6]

The competing conception of Roman Dmowski (1864-1939), labeled as “incorporational”, finally won out. Dmowski advocated the incorporation of as many territories in the east as possible and the Polonization of national minorities. Additionally, on the basis of the right to self-determination, he demanded the incorporation of ethnic Polish territories in Prussian Poland, where Poles represented – in the contrast to the kresy wschodnie (eastern borderland ) – the lower social strata. Dmowski furthermore intended to incorporate a part of Silesia, which the Polish state had lost in the 14th century, and the Masuria region, which had never belonged to Poland.[7]

One reason for the failure of the federalist conception was, clearly and inarguably, the lack of interest of the neighbouring nations. These were striving to build their own nation states in order to emancipate themselves from – among other things – Polish hegemony, which could endanger their new identity and sovereignty. As a result of Peace of Riga, which ended the Polish-Soviet War in March 1921, Ukrainian and Belarusian terrains were finally divided between Poland and the Soviet Union, and the Vilnius (Wilno) region was incorporated into Poland in 1922.[8]

The Baltics↑

The emergence of statehood in the Baltics started out very differently for Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia, but eventually all three states had to defend and consolidate their territories and political organizations within the same context: the Russian Civil War and the Polish-Soviet War.

The political parties in the Baltics had their roots mainly in the Russian Revolution of 1905 and the years immediately preceding it. The oldest political parties with a clear regional roots were social democrats, with the Lithuanian Social Democratic Party (Lietuvos socialdemokratų partija) having been founded in 1896, the Latvian Social Democratic Workers’ Party (Latvijas Sociāldemokrātiskā Strādnieku Partija) in 1904 (although it was a merger of two regional parties established in 1901 and 1902), and the Estonian Social Democratic Workers’ Party (Eesti Sotsiaaldemokraatlik Tööliste Partei) in 1905.[9]

Only slightly later did bourgeois parties with national agendas emerge, containing mostly members of the intelligentsia, many of whom were from peasant families. The Latvian Democratic Party (Latviešu Demokrātiskā partija) and the Estonian Progressive People’s Party (Eesti Rahvameelne Eduerakond) were founded in 1905, the Lithuanian Democratic Party (Lietuvių demokratų partija) in 1906.[10]

In general, the reach of political parties in the Russian Empire’s northwest was rather limited, with the social democrats being the only parties that exerted a certain political attraction. Parties served more as interest groups around political newspapers than as real political parties.[11] However, although only few of their representatives were voted into the Imperial Duma, the new parliament served as an important testing ground for politicians and was thus crucial for the formation of the national political elites.[12]

When the Germans occupied Lithuania in 1915, the majority of the intelligentsia left with the retreating Russian army. The Russian city of Voronež became a centre for Lithuanian refugees, where they developed ideas of Lithuanian nationalism and statehood. By 1917, the political lines there were divided between supporters of Bolshevism and those of the Lithuanian War Relief Committee, the latter of which demanded autonomy, and was increasingly recognised as a unified political Lithuanian voice by Russian intellectuals.[13]

When the German army invaded Courland, Latvian intellectuals and political activists partly went to Riga and partly retreated into Russia, with members across the whole political spectrum increasingly demanding a model of an autonomous Latvia within a Russian state. A large number of Latvian intellectuals gathered around the Latvian Central Welfare Committee in Petrograd. Particularly influential was a group of Latvians who had fled to Moscow, founding there the Latvian National Democratic Party (Latviešu Nacionāldemokrātu partija) in 1917.[14]

Lithuania and Courland remained occupied for the whole remaining period of the war, forming, together with the region around Białystok and Grodno, the Ober Ost military state. The military administration did not allow any political participation by the local intelligentsia and forbade any political activity, under which it also subsumed cultural and educational activities such as the founding of new schools. In general, Ober Ost officials regarded the Lithuanian population as unfit for political self-rule and expected them to be grateful for a German elite that would save them from absorption into Polish culture and at the same time furnish them with an elaborate and refined German political culture.[15] Courland was to be prepared for annexation into the German Empire.[16]

In Estonia and the unoccupied part of Latvia, demands for autonomy or even independence intensified with the Russian Revolutions of February and October 1917. When the Provisional Government restored the Finnish constitution on 6 March 1917, Estonian politicians started pushing for extensive reforms, including the unification of Estonia governorate with the northern part of Livonia governorate to include one administrative territorial unit of mostly ethnic Estonians, the introduction of local self-government, and the abolishment of Baltic-German diets. These demands were met on 30 March. In Riga, a convention of Latvian political parties on 22 July 1917 showed that all political forces – including socialists – favoured an autonomous Latvia within a democratic Russia. By this point, however, the Latvian National Democratic Party in Moscow was already advocating an independent Latvian State.[17]

By this time, the German occupants had begun seeing a Lithuanian state, which was tied closely to the German Empire, as a useful counterweight to a future Polish state, and thus allowed Lithuanian activists to form a state council (Taryba) in September 1917, the aim of which was the creation of a Lithuanian state. Acting on its own authority, the Council declared independence on 16 February 1918. In the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, signed on 3 March, Soviet Russia ceded substantial parts of the imperial western periphery to Germany, among them the territories covering today’s Ukraine and the later Baltic States. According to German plans, Lithuania was to be a semi-independent state with a sovereign of German descent (as were the other new states to be created in the region). On 23 March, Germany recognised Lithuanian statehood, ignoring, however, the council’s declaration of independence. On 11 July 1918, Wilhelm Karl von Urach (1864–1918) was proclaimed King Mindaugas II of Lithuania, but the further developments of the war prevented him from ever commencing his reign.[18]

After the Bolsheviks came to power in Russia, a Provincial Assembly (Maapäev) was formed in Estonia on 28 November 1917, which seized the opportunity of the retreat of the Bolshevik army to proclaim an independent Estonian state on 24 February 1918. This declaration became an important point of reference for future claims to the recognition of Estonian statehood. The next day, Tallinn was occupied by German troops. With the occupation, Latvian and Estonian local political activities ground to a halt, as the military administration cooperated exclusively with the Baltic German nobility.[19]

The German defeat in November 1918, the ensuing annulment of the Brest-Litovsk treaty, and the ongoing Civil War in Russia offered political activists in the region the historic opportunity to establish independent states based on the formerly marginalised, mostly peasant, majority ethnic groups. The Latvian People’s Council (Tautas padome) declared independence on 18 November 1918. While a multitude of state and territorial orders had been discussed over the course of the war, including a Lithuanian-Latvian federation, a new federal state in the territory of the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania, or a Polish-Lithuanian federation,[20] all three states were proclaimed as democratic republics within – at least theoretically – ethnically defined borders and with relatively pronounced laws of minority protection – political features necessary not least because support was needed from the Western Entente against Bolsheviks, the White Armies, and the Freikorps.[21] In Lithuania, Christian democrats and agrarianists emerged strongest from the elections for a constituent assembly (14-15 April 1920), while in Latvia (17-18 April 1920) and Estonia (5-7 April 1920), social democrats were the strongest parties, with agrarianists second.

The territories of the new states were officially consolidated in peace treaties with Bolshevik Russia, signed on 2 February (Estonia) in Tartu, 12 July (Lithuania) in Moscow, and 11 August 1920 (Latvia) in Riga, although it remains disputable whether these would have remained in effect had the Polish-Soviet War not been decided in Poland’s favour. The territory of Lithuania, however, delineated at its southern border by the Suwałki Agreement with Poland (7 October 1920) remained disputed for the whole interwar period, as a professedly renegade Polish army occupied Vilnius, claimed by Lithuania as capital city, on 9 October, while Lithuania annexed the East Prussian Klaipėda region in 1923, thus poisoning Lithuanian-German relations.[22]

The Western Entente, having become the main ally for the emerging states after the German defeat, hesitated to support Lithuanian, Latvian, and Estonian statehood. As opposed to Poland, this had never been discussed during the war, as the diaspora of these nations was smaller than the Polish and also less politicised and less well-connected with the centres of power in Western Europe and the USA. Moreover, against the backdrop of territorial claims made by an increasing number of seemingly obscure groups, and soaring ethnic violence against minority groups (especially Jews), politicians in France, Great Britain and the USA grew ever more critical of the concept of the self-determination of nations.[23] At the same time, anti-Bolshevism grew, and the Western Entente’s politicians strengthened their support of the White Armies and Russian territorial integrity. Only in 1922, after accepting the White defeat and the Bolsheviks’ consolidation of power, did the Entente recognise the Baltic states de jure as independent republics.[24]

Conclusion↑

The war plans of the victorious powers included reshaping the political map of Europe according to republicanism and democracy, regarding national self-determination and sovereignty as fundamental to a new, post-war order. The shaping of a new post-war territorial order in East Central Europe took place amidst the different, mutually exclusive territorial claims, military operations, and paramilitary violence in which conflicting sides used sets of historical, legal, religious, economic, and strategic arguments. It was established finally in the early 1920s as a result of many factors: the military outcome of the First World War, the break-up of multinational empires, the Russian revolutions, decisions made by victors during and after the Paris Peace Conference,[25] military clashes,[26] the fiasco of building independent Ukrainian and Belorussian states, political negotiations and, last but not least, plebiscites (Masuria, Silesia).

Almost no party was fully satisfied with this outcome, and the new territorial order remained very fragile and questioned by many states, which regarded them as temporary. As a result, common expectations of land reform and more socially-oriented policies could not be easily realised in these politically unstable countries.

Klaus Richter, University of Birmingham

Piotr Szlanta, University of Warsaw

Section Editors: Ruth Leiserowitz; Theodore Weeks

Notes

- ↑ Kotowski, Albert S.: Zwischen Staatsräson und Vaterlandsliebe. Die Polnische Fraktion im Deutschen Reichstag 1871-1918, Düsseldorf 2007; Trzeciakowski, Lech: Posłowie polscy w Berlinie 1848-1928 [Polish Deputies in Berlin 1848-1928], Warsaw 2003; Grodziski, Stanisław: Sejm Krajowy galicyjski 1861-1914 [The Diet of Galicia], Warsaw 1993; Ajnenkiel, Andrzej: Historia sejmu polskiego [History of the Polish Sejm], vol. 2, part 1, Warsaw 1989; Gawrecki, Dan: Der Landtag von Galizien und Lodomerien, in: Rumpler, Helmut / Urbanitsch, Peter (eds.): Die Habsburgermonarchie 1848–1918, Band VII/2, Vienna 2000, pp. 2131-2170.

- ↑ Łazuga, Waldemar: “Rządy polskie” w Austrii. Gabinet Kazimierza hr Badeniego 1895-1897 [The “Polish Governments” in Austria. The Cabinet of Count Kasimir Badeni 1895-1897], Poznań 1991; Binder, Harald: Galizien in Wien. Parteien, Wahlen, Fraktion und Abgeordnete im Übergang zur Massenpolitik, Vienna 2005.

- ↑ Zamoyski, Jan: Powrót na mapę. Polski Komitet Narodowy w Paryżu 1914-1919 [Return to the Map. The Polish National Committee in Paris 1914–1919], Warsaw 1991; Leczyk, Marian: Komitet Narodowy Polski a Ententa i Stany Zjednoczone 1917-1919 [The Polish National Committee, the Entente and the United States 1917-1919], Warsaw 1966, p. 89ff.

- ↑ Pająk, Jerzy Z.: O rząd i armie. Centralny Komitet Narodowy (1915-1917) [On Government and Army. The Central National Committee 1915-1917], Kielce 2003, pp. 68-83.

- ↑ Dmowski, Roman: Polityka polska i odbudowanie państwa [Polish Politics and the Re-establishment of the State], Częstochowa 1937, p. 229ff.

- ↑ Lewandowski, Jan: Federalizm. Litwa i Białoruś w polityce obozu belwederskiego (wrzesień 1918-kwiecień 1920) [Federalism. Lithuania and Belarus in the Politics of the Belweder Camp], Warsaw 1962; Okulewicz, Piotr: Koncepcja “międzymorza” w myśli i praktyce obozu Józefa Piłsudskiego 1918-1926 [The Concept of the “Intermarium” in Theory and Practice in the Camp of Józef Piłsudski], Poznań 2001; Nowak, Andrzej: Polska i trzy Rosje. Studium polityki wschodniej Józefa Piłsudskiego (do kwietnia 1920) [Poland and Three Russias. A Study of the Eastern Policy of Józef Piłsudski until April 1920], Kraków 2001.

- ↑ Wapiński, Roman: Endecka koncepcja polityki wschodniej w latach 1917-1921. Materiały na sesję naukową z okazji 50-lecia Wielkiej Rewolucji Październikowej [Concepts of Eastern Policy of National Democracy in the years 1917-1921. Materials of the academic session on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Great October Revolution], Gdańsk 1967; Deruga, Aleksy: Polityka wschodnia polski wobec ziem Litwy, Białoruś i Ukrainy (1918-1919) [Poland’s Eastern Policy Concerning the Lithuanian, Belarusian and Ukrainian lands (1918-1919)], Warsaw 1969.

- ↑ Gomółka, Krystyna: Między Polską a Rosją. Białoruś w koncepcjach polskich ugrupowań politycznych 1918-1922 [Between Poland and Russia. Belarus in the Concepts of Polish Political Groups 1918-1922], Warsaw 1994; Kumaniecki, Jerzy: Pokój polsko-radziecki 1921. Geneza, rokowania, traktat, komisje mieszane [The Polish-Soviet Peace 1921. Origins, Negotiations, Treaty, Mixed Commission], Warsaw 1985; Łossowski, Piotr: Konflikt polsko-litewski 1918-1920 [The Polish-Lithuanian Conflict 1918-1920], Warsaw 1996.

- ↑ Apanavičius, Romualdas: Socialdemokratai ir Lietuvos valstybingumas [The Social Democrats and Lithuanian Statehood], Vilnius 1993; Eley, Geoff: Forging Democracy. The History of the Left in Europe, 1850-2000, New York 2002, p. 63; Raun, Tovio: Estonia and the Estonians, Palo Alto 2001, p. 86; Surblys, Alvydas: Socialdemokratų ir liaudininkų veikla bei idėjos tarpukario Lietuvoje (1918–1940 m.), jų aktualumas šiandien [Activities and Ideas of Social Democrats and Populists in Interwar Lithuania 1918-1940 and their Relevance Today], online: knyga.kvb.lt/uploads/files/studija.doc (retrieved: 2 March 2013).

- ↑ Bleiere, Daina: History of Latvia. The 20th Century, Riga 2006, pp. 65-66; Miknys, Rimantas: Lietuvos demokratų partija 1902-1915 metais [The Lithuanian Democratic Party 1902-1915], Vilnius 1995; Raun, Estonia 2001, p. 84.

- ↑ Bleiere, History of Latvia 2006, p. 73.

- ↑ Cf. e.g. Gaigalaitė, Aldona: Lietuvos atstovai Rusijos Valstybės Dūmoje 1906-1917 metais [Lithuanian Deputies in the Russian State Duma 1906-1917], Vilnius 2006; Tsiunchuk, Rustem: Peoples, Regions, and Electoral Politics. The State Dumas and the Constitution of New National Elites, in: Burbank, Jane et al. (eds.): Russian Empire. Space, People, Power, 1700-1930, Bloomington 2007, pp. 366-397, here pp. 389-395.

- ↑ Balkelis, Tomas: The Making of Modern Lithuania, London 2009, pp. 112-114.

- ↑ Priedite, Aija: Latvian Refugees and the Latvian National State during and after World War I, in: Gatrell, Peter / Baron, Nick: Homelands. War, Population and Statehood in Eastern Europe and Russia, 1918-1923, London 2004, pp. 35-52, here pp. 38-40.

- ↑ Strazhas, Abba: Deutsche Ostpolitik im Ersten Weltkrieg. Der Fall Ober-Ost 1915-17, Wiesbaden 1993, pp. 71-107; Liulevicius, Vejas Gabriel: War Land on the Eastern Front. Culture, National Identity and German Occupation in World War I, Cambridge 2000, p. 124-125.

- ↑ Janßen, Karl-Heinz: Die baltische Okkupationspolitik des Deutschen Reiches, in: Hehn, Jürgen von (ed.): Von den baltischen Provinzen zu den baltischen Staaten. Beiträge zur Entstehungsgeschichte der Republiken Estland und Lettland 1917-1918, Marburg 1971, pp. 217-254.

- ↑ Raun, Estonia 2001, p. 100; Priedite, Latvian Refugees 2004, p. 39.

- ↑ Demm, Eberhard: Anschluss, Autonomie oder Unabhängigkeit? Die deutsche Litauenpolitik im Ersten Weltkrieg und das Selbstbestimmungsrecht der Völker, in: Journal for Baltic Studies 25/2 (1994), pp. 195-200; Tauber, Joachim: Die Last der Geschichte. Zu den Vorstellungen der Taryba über den zukünftigen litauischen Staat 1917−1918, in: Angermann, Norbert et al. (eds.): Ostseeprovinzen. Baltische Staaten und das Nationale, Münster 2005, pp. 389-402.

- ↑ Nelson, Robert L.: The Baltics as Colonial Playground. Germany and the East, 1914-1918, in: Journal of Baltic Studies 42/1 (2011), pp. 9-19; Raun, Estonia 2001, p. 106.

- ↑ Miknys, Rimantas: Stosunki polsko-litewskie w wizji politycznej krajowców [Polish-Lithuanian relations in the political visions of the Krajowcy], in: Zeszyty Historyczne 104 (1993), pp. 123-129.

- ↑ Richter, Klaus: Eine durch und durch demokratische Nation. Demokratie und Minderheitenschutz in der Außendarstellung Litauens nach 1918, in: Zeitschrift für Ostmitteleuropa-Forschung 64/2 (2015), pp. 194-217.

- ↑ Laurinavičius, Česlovas (ed.): Suvalkų sutartis. Faktai ir interpretacijos/Umowa Suwalska. Fakty i interpretacje [The Suwałki Treaty. Facts and Interpretations], Vilnius 2012; Debo, Richard K.: Survival and Consolidation. The Foreign Policy of Soviet Russia, 1918-1921, Quebec 1992, esp. pp. 191-212; Weeks, Theodore: Vilnius between Nations, 1795-2000, DeKalb 2015.

- ↑ Fink, Carole: Defending the Rights of Others. The Great Powers, the Jews and International Minority Protection, 1878-1938, New York 2004; Finney, Patrick B.: “An Evil for All Concerned.” Great Britain and Minority Protection after 1919, in: Journal of Contemporary History 30/3 (1995), pp. 533-551; Neuberger, Benjamin: National Self-Determination. A Theoretical Discussion, in: Nationalities Papers, 29/3 (2001), pp. 391-418.

- ↑ Carley, Michael Jabara: Episodes from the Early Cold War. Franco-Soviet Relations, 1917-1927, in: Europe-Asia Studies, 52/7 (2000), pp. 1275-1305; Hovi, Kalervo: Cordon sanitaire or barrière de l'est? The emergence of the New French Eastern European Alliance Policy, 1917-1919, Turku 1975; Little, Douglas: Antibolshevism and American Foreign Policy, 1919-1939. The Diplomacy of Self-Delusion, in: American Quarterly 35/4 (1983), pp. 376-390.

- ↑ Kumaniecki, Pokój polsko-radziecki 1985, pp. 38-62; Borzęcki, Jerzy: The Soviet-Polish Peace of 1921 and the Creation of Interwar Europe, New Haven and London 2008; Przyłuska-Brzostek, Marta: Ekspertyzy i materiały delegacji polskiej na konferencję wersalską 1919 roku [Expertise and Materials of the Polish Delegation to the Versailles Conference in 1919], Warsaw 2009.

- ↑ Wrzosek, Mieczysław: Wojny o granice Polski Odrodzonej 1918-1921 (The Wars for the Borders of Reborn Poland 1918-1921), Warsaw 1992; Łossowski, Piotr: Konflikt polsko-litewski 1918-1920 [The Polish-Lithuanian Conflict 1918-1920], Warsaw 1920; Klimecki, Michał: Polsko-ukraińska wojna o Lwów i Galicję Wschodnią 1918-1919 [The Polish-Ukrainian war over Lwów and Eastern Galicia 1918-1919], Warsaw 2000.

Selected Bibliography

- Balkelis, Tomas: The making of modern Lithuania, London; New York 2009: Routledge.

- Bleiere, Daina et al.: History of Latvia. The 20th century, Riga 2006: Jumava

- Borzęcki, Jerzy: The Soviet-Polish peace of 1921 and the creation of interwar Europe, New Haven 2008: Yale University Press.

- Demm, Eberhard / Noël, Roger / Urban, William L. (eds.): The independence of the Baltic states. Origins, causes, and consequences. A comparison of the crucial years 1918-1919 and 1990-1991, Chicago 1996: Lithuanian Research and Studies Center.

- Kidzińska, Agnieszka: Stronnictwo Polityki Realnej, 1905-1923 (The Party of Realist Politics, 1905-1923), Lublin 2007: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Marii Curie-Skłodowskiej.

- Laurinavičius, Česlovas / Milewski, Jan Jerzy (eds.): Suvalkų sutartis. Faktai ir interpretacijos. Umowa Suvalska. Fakty i interpretacje (Suwalki agreement. Facts and interpretations), Vilnius 2012: Versus Aureus.

- Miknys, Rimantas: Lietuvos Demokratu̜ Partija 1902-1915 metais (The Lithuanian Democratic Party 1902-1915), Vilnius 1995: A. Varno Personalinė I̜monė.

- Okulewicz, Piotr: Koncepcja 'międzymorza' w myśli i praktyce politycznej obozu Józefa Piłsudskiego w latach 1918-1926 (The concept of the 'Intermarium' in idea and practice of the camp of Józef Piłsudski), Poznań 2001: Wydawnictwo Poznańskie.

- Pajewski, Janusz: Odbudowa państwa polskiego 1914-1918 (The reconstruction of the Polish state 1914–1918), Warsaw 1978: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.

- Przenioslo, Marek: Polska Komisja Likwidacyjna 1918-1919 (The Polish Liquidation Commission 1918-1919), Kielce 2010: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Humanistyczno-Przyrodniczego Jana Kochanowskiego.

- Przyłuska-Brzostek, Marta: Ekspertyzy i materiały delegacji polskiej na konferencje̜ wersalska̜ 1919 roku (Expertise and materials of the Polish delegation to the Versailles Conference in 1919), Warsaw 2009: Polski Instytut Spraw Mie̜dzynarodowych.

- Raun, Toivo U.: Estonia and the Estonians, Stanford 2001: Hoover Institution Press, Stanford University.

- Swiętek, Ryszard: Lodowa ściana. Sekrety polityki Józefa Piłsudskiego 1904-1918 (Wall of ice. The secret policies of Józef Piłsudski 1904-1918), Krakow 1998: Platan.

- Szymczak, Damian: Między Habsburgami a Hohenzollernami. Rywalizacja niemiecko-austro-węgierska w okresie I wojny światowej a odbudowa państwa polskiego (Between Habsburgs and Hohenzollerns. The German-Austro-Hungarian rivalry in the period of World War I and the construction of the Polish state), Krakow 2009: Wydawnictwo Avalon.

- Tsiunchuk, Rustem: Peoples, regions, and electoral politics. The state Dumas and the constitution of new national elites, in: Burbank, Jane / Von Hagen, Mark / Viktorovič Remnëv, Anatolij (eds.): Russian Empire. Space, people, power, 1700-1930, Bloomington 2007: Indiana University Press, pp. 366-397.

- Wapiński, Roman: Narodowa Demokracja, 1893-1939. Ze studiów nad dziejami myśli nacjonalistycznej (National democracy 1893-1939. From studies on the history of nationalist thought), Wrocław 1980: Ossolineum.

- Wapiński, Roman (ed.): Endecka koncepcja polityki wschodniej w latach 1917-1921. Materiały na sesję naukową z okazji 50-lecia Wielkiej Rewolucji Październikowej (Concepts of the eastern policy of national democracy in the years 1917-1921. Materials of the academic session on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of the Great October Revolution), Gdańsk 1967: WSP.

- Wa̜tor, Adam: Narodowa demokracja w Galicji do 1918 roku (National democracy in Galicia until 1918), Szczecin 2002: Wydawnictwo Naukowe Uniwersytetu Szczecińskiego.

- Weeks, Theodore R.: Vilnius between nations, 1795-2000, DeKalb 2015: NIU Press.

- Zamoyski, Jan: Powrót na mapę. Polski Komitet Narodowy w Paryżu 1914-1919 (Return to the map. The Polish National Committee in Paris 1914–1919), Warsaw 1991: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe.