Introduction↑

The “war movie” was a popular production and reception category in many European countries during the First World War. Able to combine seemingly disparate elements such as entertainment, propaganda and the impression of an authentic representation of the war, the importance of these movies goes beyond a historical audio-visual record of the conflict. War movies can also provide an insight into the institutionalization process of the cinema at a time when its social and cultural functions, as well as its accepted subjects and forms, were still being negotiated.

Studying war movies in Portugal during the First World War presents significant challenges to the historian. First, contemporary sources make only fleeting references to these movies, as cinema was still in the process of gaining a foothold in Portuguese society during the 1910s. This probably explains why there are no studies about this particular subject. Survey studies of Portuguese cinema make only brief references to the First World War and existing film catalogues prove unreliable when one tries to establish a basic filmography of relevant titles. Second, even though an official film propaganda office was created in 1917, its output was scarce and limited to non-fiction cinema. Other production companies also stuck to non-fiction. João Ratão, directed by Jorge Brum do Canto (1910-1994), the first Portuguese fiction film about the First World War, was only shot in 1940. Third, this shrunken corpus of war movies is further shortened by the fact that not many archival prints have survived. The assessment of both state-backed movies and ones produced by commercial companies thus proves difficult.

This scarcity was compensated, and perhaps even stimulated in the first place, with the distribution of allied propaganda films, mostly of English, French, and American origin. If it were not for these films, Portuguese audiences would not have seen any footage of their troops fighting on the European front.

This article will begin by reviewing the available information about official Portuguese propaganda war movies. It will continue with remarks on some of the allied films about the Portuguese troops fighting in Europe. It will end with a short analysis of the only Portuguese fiction film about World War I. Given the lack of information about film releases in Portugal up to 1918, this article will make no reference to foreign fiction movies about the war.

The First Official Films↑

The Portuguese visual propaganda services were created to cover and promote the presence of national troops on the European front after January 1917. There is no evidence of the production of any official movies concerning the troops sent to the Portuguese colonies in Africa, Angola and Mozambique during 1914 and 1915. These events seem to have mostly been covered by Portuguese commercial film companies which limited themselves to shooting the troops' send-off parades and the departures of their naval transports from Lisbon. There is also no evidence that any film showing the activity of these troops in Africa had been shot or shown in Portugal during the war.

Portugal officially entered the war in March 1916. In August and September 1916, the Ministry of War produced two feature documentaries about the preparations of the Portuguese troops who were to be sent to France. The success of these films is likely to have persuaded both the government and the military authorities of the usefulness of the cinema to promote the country’s participation in the war, as well as of the convenience of having such a persuasive propaganda tool under strict state supervision. Eventually, this led to the creation of an official film propaganda service in early 1917.

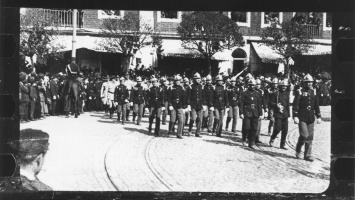

Of the two 1916 films, the first one, titled Os Exercícios Militares em Tancos: Grande Parada em Montalvo [Military Exercises in Tancos: Big Parade in Montalvo], was premiered in Lisbon on 8 August 1916 in Coliseu dos Recreios, one of the largest vaudeville theatres of the capital. With five parts and 2,500m long (about ninety minutes), it was a thorough representation of the Portuguese expeditionary force. It covered the final exercises of the Portuguese troops in the training camp of Tancos and a grand parade of 20,000 men in the near town of Montalvo. It was later premiered in Porto, the country’s second biggest city, on 29 August 1916 in two movie theatres simultaneously.

Portugal na Guerra: Divisão Naval Portuguesa [Portugal at War: The Portuguese Naval Division] was also premiered in Lisbon on 21 September 1916 in Salão Central, an important first run movie theatre. With six parts, it showed life on board the Portuguese Navy ships and several naval and submarine warfare exercises. It was also shown in Porto on 4 October 1916 in two separate movie theatres.

Both films were supervised by an army officer, Captain Carlos Nogueira Ferrão (1871-1938), and shot by Ernesto de Albuquerque (1883-1940), the most experienced Portuguese cameraman of the 1910s. Ferrão had been actively involved in the movie business since the 1900. A stockholder of different movie theatres and distribution companies, including Salão Central where the second film was released, Ferrão would later become the director of the army’s official film service. Albuquerque, a former croupier, inherited his father’s photography business and started shooting one-reel comedies and newsreels in 1916. In the 1920s, when fiction filmmaking kicked off in Portugal, Albuquerque was one of the most popular cameramen.

In 1916, there were no film magazines in Portugal and no film sections in the newspapers. However, the few articles in the press about the movies suggest an enthusiastic reception.[1] Both movies contained much anticipated footage of the Portuguese troops which helped silence critics of the governmental rhetoric about the “Tancos’ miracle” (i.e., the preparation of the troops in record time). The exercises were also received in anticipation of coming combat footage, which, as we will see, was never actually shot by Portuguese cameramen. All newspapers reported that the unfortunate death of a cavalry officer during the exercises was removed from the released version of the film, a piece of information that consolidated the impression of both the intensity of the exercises and the authenticity of the films.[2] This authenticity effect was further enhanced by the massive number of troops in the parade that ended the first film. This was repeatedly described by various sources as the most impressive sequence of the movie.[3] Just as it had happened in France and in Britain, these films were actively promoted as “official,” contrary to the anonymity principle governing literary propaganda, a decision that proved to be a strong selling point.

Even if Albuquerque was the only official cameraman allowed full access to Tancos by the Ministry of War, the fact that the exercises were public events meant that they could be easily shot by commercial film companies.[4] This was the case for Invicta Film which released two films about the same events with the almost exact same titles, tailing and sometimes anticipating the army films’ release dates. Shot by Manoel Cardoso, A Mobilização Portuguesa em Tancos [Portuguese Mobilization in Tancos], with two parts and 1,200m, was first released in Porto, where Invicta Film was based, in early August (before the national release of the army’s film about the same event in Lisbon, according to one source)[5]. Also shot by Cardoso, Manobras da Divisão Naval Portuguesa [Manoeuvres of the Portuguese Naval Division], with two parts and 1,500m, was released in Lisbon on 22 September 1916, one day after the army’s film release, and in Porto on 1 October 1916, three days ahead of the army film’s premiere. This cutthroat competition makes it clear why the army insisted on promoting its films as the only “official” ones about those events at the same time as it tried to restrict full access to the troops. It would be important to assess the differences between these films, the only images of the preparations of the Portuguese troops deployed to the European front, but unfortunately no archival prints of any of these films have survived.

The Portuguese Army’s Photographic and Cinematographic Service↑

As in other allied countries, official Portuguese film propaganda was used alongside other visual propaganda forms and dispersed through different institutions that often acted in a competitive or outright contradictory way. A Photographic Section (SF) was operating in January 1917 under the Portuguese General Headquarters in France. A report from the Section Photographique de l’Armée Française, re-sent from the Romanian Army, stated the objectives of such a section and how it should be organised, including very precise indications about which subjects should be photographed. An Art Service was also operating in 1917, again under the supervision of the Portuguese HQ. A third visual propaganda official body, the Portuguese Army’s Photographic and Cinematographic Service (SFCE), was launched in March 1917 under the supervision of Lieutenant-Colonel Desidério Beça (1868-1920), head of the 4th section of the Ministry of War. This was the first official film service created by the Portuguese state. Under different names, it survived two regime changes (the dictatorship after the 1926 military coup and the parliamentary democracy after the 1974 revolution) and had an important role covering the colonial wars of 1961-1974. It remained active into the 1980s. The SFCE was clearly inspired by French and English models as it comprised photographic and film sections as well as an art section. Like their allied counterparts, the SFCE was also as much interested in generating visual propaganda to be used right away as it was invested in creating a historical record of the war.

The SF consisted of one photographer, Arnaldo Garcez Rodrigues (1885-1964), who documented the entire training process in Portugal and England as well as combat operations in France. Because the Portuguese troops were under British command, Garcez’s work was subjected to British military censorship. The Portuguese Army records show that the Portuguese military command repeatedly objected to this censorship, but to no avail. Garcez’s photos were mostly used in foreign publications and inter-allied photographic exhibitions that were only shown in Portugal after the end of the war. This outraged Portuguese magazine editors, some of whom tried to circumvent the problem by publishing amateur photos taken by Portuguese soldiers, an act strictly forbidden by military regulations. The work of painter Adriano de Sousa Lopes (1879-1944), the only known activity of the Art Service, was also mostly displayed long after the war and it only found a permanent exhibition venue in the World War I wing of the Military Museum in Lisbon in 1936.

The SFCE was originally intended to promote patriotic feelings amongst the Portuguese troops and Portugal amongst its allies. This means that the SFCE did not necessarily envisage itself as a producer of war movies or even of topical films for that matter, but rather of documentaries about Portugal.[6] In fact, after the end of the war, this type of film was to become the main output of the SFCE, especially after the military coup of 1926.

During the war, and much to the disappointment of the home front, the SFCE did not produce any films about the Portuguese troops in France. It is unclear why this happened and whether if it was due to any internal hesitations or to tensions with the British command, as it had been the case with photographic propaganda.

The first known SFCE film is Festa das Alunas do Instituto Feminino de Educação e Trabalho [Party of the Women’s Institute of Education and Work Students], released in Lisbon on 10 June 1917, a non war-related documentary about a school for the daughters of military personnel. During the following months, the SFCE’s film production was directed at the war effort of the home front, showing training exercises and military schools, as well as the departure of military units for France. Known film titles include Provas Finais dos Alunos da Escola de Guerra [Final Exams of the School of War Students] (released on 19 October 1917), Lançamento da Canhoneira “Bengo” [Launch of the Gunboat “Bengo”] (11 November) and Juramento de Bandeira na Escola de Guerra [Flag Allegiance Ceremony at the School of War] (17 November). Entrega da Bandeira da Cidade de Lisboa ao Cruzador “Vasco da Gama,” [Handover of the Flag of the City of Lisbon to the Cruiser “Vasco da Gama”], Escola de Aviação em Vila Nova da Rainha, Escola de Oficiais Milicianos em Queluz [School of Aviation in Vila Nova da Rainha], and Transporte de Tropas para França [Troops Transport to France] were released collectively in a special event in Lisbon on 22 October 1917. All the films seem to have been shot by Augusto Ribeiro Seara, an Army sergeant who would work with the SFCE throughout the 1920s and 1930s.

Earlier in 1917, a film titled Tropas Portuguesas no Front [Portuguese Troops on the Front Line](released on 24 July 1917) was promoted as the first showing the Portuguese troops in France but there is no evidence that this was actually a Portuguese film. The same might be true of a film about the visit of President Bernardino Machado (1851-1944), released in Lisbon and Porto in late November. In fact, during the war and as late as 1928, SFCE is known to have organized special screenings of allied “war movies” and these 1917 screenings might just be early examples of that.

Some sources indicate that Ernesto de Albuquerque, who had shot the Army’s 1916 films, was getting ready to shoot in France but he was prevented from doing so because of the December 1917 coup,[7] which brought Sidónio Pais (1872-1918) to power and changed the Portuguese war policy, interrupting the sending of supplies and reinforcements to the front. The 1917 coup further disrupted the activity of SFCE by turning it away from the war effort in order to promote the public appearances of Sidónio Pais, himself an army major. In late 1917 and throughout 1918, SFCE mostly covered his presidential visits across the country and other public events attended by Pais. During this period, the only war-related movie shot by the SFCE showed the public demonstrations in Lisbon after the Armistice. The assassination of Sidónio Pais in December 1918 caused a significant national commotion and SFCE’s films of the funeral ceremonies attracted large crowds to the movie theatres.

After the Armistice, the SFCE’s most important war-related movie covered the memorial ceremonies accompanying the burial of the two Portuguese unknown soldiers in Batalha on April 1921 (Glorificação dos Soldados Desconhecidos Mortos na Grande Guerra [Tribute to the Unknown Soldiers Fallen in the Great War], four parts, released on 21 April 1921).

Allied Propaganda Films↑

Portuguese audiences depended on foreign, specifically allied-produced war movies, to watch the Portuguese troops in France or, for that matter, to watch any footage of the front lines. French, British and later American newsreels as well as feature documentaries were regularly shown in the main cities’ movie theatres. Special screenings, organized either by movie theatre owners, the SFCE or allied embassies, shaped the extraordinary nature of war movies. As early as September 1914, a special screening was organised at Salão Central in Lisbon, of which the aforementioned Captain Ferrão was one of the owners. The screening was promoted with a generic “war movies” reference.[8] In July 1916, a movie theatre in Porto announced “European war films” in the Kinemacolor process featuring French and British airplanes.[9] In January 1918, it was Lisbon’s time to watch a series of animated educational movies about American planes made by Bray Studios.[10] Finally, on 19 September 1918, a special screening at Olímpia gathered all allied ambassadors in Lisbon, military and naval attachés, as well as several Portuguese military and civil authorities, to honour the allied powers.[11]

Portuguese newspapers refer to only a few movies about the Portuguese troops on the European front. However, because in this period movies were never clearly identified in the press, it is difficult to cross-reference those movies with known French and British movies about the same subject. We can be confident that A Visita do Presidente da República Portuguesa às Linhas Francesas [Visit of the President of the Portuguese Republic to the French Front Lines], a 1917 documentary produced by the Section Cinématographique de l’Armée Française about the visit of President Machado to the Portuguese troops in France was shown in Portugal in October 1917. The Portuguese Film Archive holds a print with Portuguese subtitles, a clear indication that it was intended for distribution in Portugal.

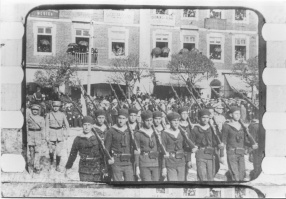

Tropas Portuguesas em França [Portuguese Troops in France] (released in Lisbon on 7 September 1917) and Tropas Portuguesas em Inglaterra [Portuguese Troops in England] (Lisbon, 10 October 1918) were mentioned in Portuguese newspapers, and might correspond to any of a small group of prints held at the Imperial War Museum: With the Portuguese Expeditionary Force in France (Topical Film Company, 1917), A Portuguese Training Camp in England (1918) and Portuguese Troops in France (1918?). In any case, these British movies in the IWM collection are precious historical documents with unique images of the training and daily life in the trenches of Portuguese infantry and artillery units, including several mock and actual combat sequences.

Of a gloomier nature, Afundamento do “Augusto Castilho” [The Sinking of the “Augusto de Castilho”] is an amateur movie shot by the crew of the German U-Boat that sank a Portuguese patrol boat in the north Atlantic on 18 October 1918. Recovered by the Portuguese Film Archive long after the end of the war, little is known about the production context of this movie and the material history of its prints. This movie shows us, in the crudest possible way, what most propaganda movies did their best to keep away from the home front audiences.

To cope with the growing number of Portuguese and foreign war movies, the Government instituted film censorship in August 1917 overseen by the Ministry of War. This was five months after the creation of the SFCE and eight months after the deployment of Portuguese troops on the European front. Unlike postal and newspaper censorship, film censorship was not revoked after the end of the war and survived until 1928 when it was transformed into something much more efficient and systematic by the military dictatorship.

João Ratão (1940): The Only Portuguese Fiction Film about World War I↑

After the 1926 military coup and up to the early 1930s, many Portuguese documentaries and fiction films often involved military characters or sequences using military personnel and installations. It was in this context that O João Ratão [John Shrew], an extremely popular 1920 stage operetta, was first considered for a movie adaptation in 1931.[12] A cheerful celebration of military honour, the project was certainly aligned with the worldview of the military dictatorship. It was also in striking opposition to the international pacifist mood of the 1930s which originated films like All Quiet on the Western Front Lewis Milestone (1895-1980), 1930], Westfront G. W. Pabst (1865-1967), 1930], Niemandsland Victor Trivas (1896-1970), 1931], La Grande Illusion Jean Rouch (1917-2004), 1937], and J’Accuse Abel Gance (1889-1981), 1938], among others.

The project was dormant until 1940 when Tobis Portuguesa decided to produce it, hiring Jorge Brum do Canto, one of the most renowned Portuguese filmmakers, to direct it. Faithful to the jingoistic and cheerful mood of the operetta, the movie tells the story of a World War I soldier, João Ratão, as he returns from the European front to his village in rural Portugal. João is received as a “war hero” but his bully nature, as well as his bragging about the Germans and his affairs with French women, soon arouses the jealousy of some of the other villagers who contrive to discredit him.

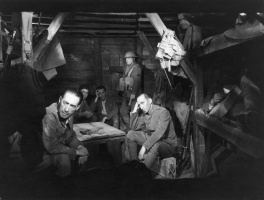

The atmosphere of trench warfare is reconstructed using archival footage and studio sets in a couple of brief sequences in the beginning of the film, before João’s return home. Most of the action, therefore, takes place in João’s village, whose community is an obvious pastoral version of the country, a safe environment outside of which characters will only find misfortunes such as war, women or, in a word, modernity.

In this sense, João Ratão balances two seemingly opposite ideas. On the one hand, the movie makes insistently clear that the military bravery of Portuguese soldiers is not to be questioned, while on the other, it states that the outside world is best left alone. It is impossible not to interpret João Ratão in the context of Portugal’s neutrality during the Second World War, much capitalized on by the regime’s propaganda as an extraordinary personal achievement of its dictator, even if it was as much a domestic decision as one imposed by the interests of both the Allied and the Axis powers alike as their reasons are incomprehensible. Similarly, João Ratão argues that international wars are as distant as their reasons and that Portugal would do best to keep away from this conflict and unite under the regime that had accomplished neutrality.

Conclusion↑

As in many other belligerent countries, “war movies” attracted the attention of Portuguese audiences during the First World War. Even if problematic sources and the scarcity of surviving prints have hindered research on this subject, at least two important issues seem worth pursuing.

In spite of the creation of an official army cinematographic service in early 1917, it was only thanks to the allied films that Portuguese audiences were to see the Portuguese troops deployed in France after January 1917. This vexing fact did not go unnoticed at the time and it weighted heavily on jingoistic feelings. However, it was a direct consequence of the contradictory situation of the cinema in Portugal during this period. On the one hand, there was an underdeveloped production sector which by August 1914 had still failed to have originated any significant fiction films, let alone features; but on the other, the exhibition and distribution sectors were booming, though almost entirely dependent on the movie supply of both European and American production companies. The ideal of authenticity that was attached to war movies, as well as the special screenings that made them an extraordinary social event, inscribe war movies in the process of transformation of the cinema into a legitimate public show— a process at once confirmed and enhanced by the earliest examples of state intervention through the creation of the first official film service and the first film censorship system. Even if it requires further research, the hypothesis that war movies have played a role in the process of institutionalization of the cinema in Portugal will certainly prove to be productive.

In some countries, participation in the First World War was transformed into an important moment of national identity construction, repeatedly represented in the cinema and television (like in the Australian case, for example)[13]. In Portugal, on the contrary, the absence of cinematic representations of the war is quite striking. During the war, no fiction movies, official or otherwise, ever addressed the conflict. Since 1918, only one movie has taken up the subject. But even João Ratão (1940) speaks more to the context of Portuguese neutrality during the Second World War than to the First World War during which time its action takes place. The absence of the First World War from Portuguese cinema begs further research and would benefit from a comparative approach not only with other countries but also with other Portuguese cultural forms and with other conflicts in the history of Portugal.

Tiago Baptista, Cinemateca Portuguesa-Museu do Cinema / Instituto de História Contemporânea

Section Editors: Filipe Ribeiro de Meneses; Maria Fernanda Rollo; Ana Paula Pires

Notes

- ↑ Os Exercícios Militares em Tancos. Grande Parada em Montalvo [Military Exercises in Tancos. Big Parade in Montalvo], in: Diário de Notícias [Daily News] (10 August 1916); Uma Fita de Sensação. As Manobras de Tancos [A Sensational Movie. The Manouevres in Tancos], in: Diário dos Açores [Azores’ News] (28 August 1916).

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Não Achamos Bem [We Feel This is Wrong], in: A Montanha [The Mountain] (4 August 1916).

- ↑ A Mobilização Portuguesa em Tancos [Portuguese Mobilization in Tancos], in: O Tripeiro [The Tripeman] (August 1966).

- ↑ A Cinematographia na Guerra [Cinematography and the War], in: Cine Revista [Cine Journal] (15 March 1917).

- ↑ Santos, A. Videira: Ernesto de Albuquerque, Lisbon 1983.

- ↑ Fitas de Guerra [War Movies], in: A Folha de Lisboa [Lisbon’s Sheet] (27 September 1914).

- ↑ Jornal de Notícias (7 July 1916).

- ↑ Cine Revista 11 (15 January 1918).

- ↑ Os Films de Guerra [The War Movies], in: Cine Revista [Cine Journal] 20 (15 October 1918).

- ↑ De Lisboa [From Lisbon], in: Invicta Cine [Cine Invicta] 144 (14 January 1931).

- ↑ Reynaud, Daniel: Celluloid Anzacs. The Great War through Australian Cinema, North Melbourne 2007.

Selected Bibliography

- Baptista, Tiago / Sena, Nuno (eds.): Lion, Mariaud, Pallu. Franceses tipicamente portugueses (Lion, Mariaud, Pallu. Typically Portuguese Frenchmen), Lisbon 2003: Cinemateca Portuguesa.

- Bénard da Costa, João: Histórias do Cinema Português (Histories of Portuguese cinema), Lisbon 1991: Imprensa Nacional.

- Brun, André: A malta das trincheiras. Migalhas da Grande Guerra, 1917-1918 (The men in the trenches. Crumbs of the Great War, 1917-1918), Porto 1983: Livraria Civilização Editora.

- Garcia, Maria da Graça / Zink, João David: I Guerra Mundial. Cartazes da colecção da Biblioteca Nacional (World War I. Posters from the National Library collection), Lisbon 2004: Ministério da Cultura, Biblioteca Nacional.

- Grilo, João Mário: O cinema da não-ilusão. Histórias para o cinema português (The cinema of non-illusion. Histories of Portuguese cinema), Lisbon 2006: Livros Horizonte.

- Hammond, Michael: The big show. British cinema culture in the Great War, 1914-1918, Exeter 2006: University of Exeter Press.

- Martins, Luis Augusto Ferreira: Portugal na Grande Guerra (Portugal in the Great War), Lisbon 1934: Editorial Ática.

- Matos-Cruz, José de / Ferreira, António J. / Pina, Luís de: Prontuário do cinema português, 1896-1989 (Portuguese filmography. 1896-1989), Lisbon 1989: Cinemateca Portuguesa.

- Meneses, Filipe Ribeiro de: União sagrada e sidonismo. Portugal em guerra, 1916-1918 (The sacred union and Sidonism. Portugal at war, 1916-1918), Lisbon 2000: Cosmos.

- Moreira, Arbués: O Jornal dos Cinemas Visita a Secção Cinematográfica do Exército (Cine Journal's visit to the army's photography and film section), in: Jornal dos Cinemas 14, 1923, pp. 233-235.

- N.N.: Regulamento da Secção Fotográfica e Cinematográfica do Exército (Regulation of the army’s photography and film section): Ordem do Exército (Army’s order), volume 6, 1918, pp. 379-385.

- Reeves, Nicholas: Official British film propaganda during the First World War, London; Wolfeboro 1986: C. Helm.

- Ribeiro, Manuel Félix: Filmes, figuras e factos da história do cinema português, 1896-1949 (Movies, people and facts from the history of Portuguese cinema), Lisbon 1983: Cinemateca Portuguesa.

- Rosas, Fernando / Rollo, Maria Fernanda (eds.): História da primeira República Portuguesa (History of the Portuguese First Republic), Lisbon 2009: Ediçoes Tinta da China.

- Samara, Maria Alice: Verdes e vermelhos. Portugal e a guerra no ano de Sidónio Pais (Green and red. Portugal and the war in year of Sidónio Pais), Lisbon 2003: Editorial Notícias.

- Santos, Manuel Farinha dos: Sousa Lopes, Lisbon 1962: Liga Combatentes/Gulbenkian.

- Teixeira, Nuno Severiano: O poder e a guerra, 1914-1918. Objectivos nacionais e estratégias políticas na entrada de Portugal na Grande Guerra (Power and war, 1914-1918. National objectives and political strategies of Portugal’s participation in the Great War), Lisbon 1996: Editorial Estampa.

- Véray, Laurent: La Grande guerre au cinéma. De la gloire à la mémoire, Paris 2008: Ramsay.

- Vicente, António Pedro: Arnaldo Garcez. Um repórter fotográfico na 1a grande guerra (Arnaldo Garcez. A photojournalist in World War I), Porto 2000: Ministério da Cultur; Centro Portuguuês de Fotografia.