Introduction↑

This cinematic report of mobilisation from the Gaumont-Paris newsreel was typical of the way in which French newsreels of the time recorded military events. Cine cameras were heavy and unwieldy, difficult to move, and thus cinematographers placed their cameras in a fixed position and recorded only what was in front of the lens. Military parades, drills, inspections and marches were ideal material for the newsreels as they offered an ever-changing panorama of movement to the viewer from their fixed standpoint. They also reinforced popular ideas of the military but often gave a false impression of overwhelming strength. The idea of the newsreel actually originated in France in early 1908 when the Pathé Company combined several short films dealing with recent events into an entertaining review. Audiences were fascinated with events like the Messina earthquake, Louis Blériot (1872–1936) flying the Channel, great state occasions, and foreign events like the coronation of George V, King of England (1865-1936) in England. The newsreel quickly became an integral part of the cinema programme, issued twice a week and produced by companies like Gaumont, Éclair and Eclipse as well as Pathé. It is a common popular myth that the outbreak of war in 1914 was almost universally popular and greeted with great enthusiasm by most Frenchmen, but in reality it seems that while some were eager for war many others were less than enthusiastic.[2] Nevertheless to show excited crowds so eager for war was good for national morale and for the cause. Of course, for the newsreels the War was the most exciting and dramatic event of the century and they were desperate to exploit it.

Filming the War↑

The outbreak of war, however, badly affected the industry; conscription meant many filmmakers were absorbed into the army, resources became difficult to obtain, and the government’s closure of cinemas and places of entertainment meant film production virtually stopped. Although the cinemas were later re-opened, the industry was never able to regain the pre-war eminence it had enjoyed. The newsreels almost suffered the same fate, only the insatiable public demand for war news kept them afloat. Initially, cameramen were able to move about freely, their footage showed the arrival of the British Expeditionary Force, the retreat of the Belgian Army, the floods of refugees fleeing from the battle zone, and the dramatic retreat to the Marne. The government eventually decided that much of this footage did little for civilian morale and so a rigid censorship policy was put in place which severely limited what could actually be shown on screen. In 1915, however, an official of the Pathé Company persuaded the military authorities that film could actually boost morale and provide an important record of events, and official film units, Service Photographique et Cinématographique des armées, were established in most divisions. The footage they shot, although still subject to the army censor, was supplied to the commercial newsreels for screening in France and abroad. The Military also produced their own weekly newsreel, Annales de la Guerre, and some sixty documentaries.[3]

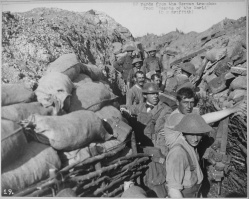

Before telephoto lenses and fast film, and with bulky, unwieldy cameras, the filmmaker was relegated to a relatively safe position behind the front line. Thus it was impossible to record the fine details of battle. Film, then, was often a disappointment to an audience weaned on graphic images of war created by the war artist and popular illustrator – often painted without even visiting the battlefield. For cinema audiences, however, film lacked what we might call "the up close and personal" detail of battle, to which the public had become accustomed through romantic fiction and popular illustrations. This technical limitation actually served government interests creating a sanitized image of war that would not depress the public or curtail the enthusiasm of future conscripts. The great American filmmaker David Llewelyn Wark Griffith (1875–1948) interestingly provides us with a curious insight into one of the problems of filming on the Western Front. Employed by the British government in 1917 to produce a major propaganda film, Griffiths was given unprecedented access to film anywhere in the frontline. But as he later explained in an interview:

"Too colossal to be dramatic" seems a curious description for the most devastating war in history, but of course most activity took place out of sight below the parapet. On most days there was remarkably little to see. Griffiths did film some establishing shots in France, but most of his war film Hearts of the World was filmed on a Hollywood sound stage while the battle sequences were recreated on Salisbury Plain in southern England using British and Canadian troops – the only way Griffiths could capture the necessary "realism" to convince audiences that they were looking at the real war.[5] So, with primitive equipment, the difficulties of filming and military censorship what exactly did the newsreels show?

Most footage was shot from the comparative safety of the rear – guns, reinforcements and supplies moving up to the front provided a sense that the war was going well for the viewer, while scenes of refugees and ruined villages induced a sense of hatred for the enemy. There was limited coverage of the great battles at Verdun or the Allied offensive on the Somme, although a documentary, The French Offensive on the Somme was released in the late summer of 1916. The cameras were well behind the attacking troops and thus what we see on screen are tiny figures in the far distance, almost lost in the man-made landscape of the battlefield. It is impossible to tell what exactly is going on or even who these distant figures are. Newsreels did not dwell on French casualties for obvious reasons and, considering it was such a static war, there are remarkably few scenes of soldiers in the trenches. Perhaps the authorities thought such scenes would affect the morale of the home front. Newsreels made few references to France’s allies apart from the British – the arrival of the British Expeditionary Force and some footage of combined offensives, but essentially the war was shown as a Franco-German struggle. There was also remarkably little coverage of events on other fronts, even though film units were stationed in Salonika and elsewhere. Not surprisingly there was no mention of the Russian Revolution in 1917, and the eventual peace treaty between the Bolsheviks and the Germans, and no reference to the French Army mutinies in the same year. Certainly General Philippe Petain (1856–1951) began to feature in the newsreels more often after the spring of 1917, and there was slightly more emphasis on the soldier’s life at the Front and behind the lines – a likely attempt to play down the rumours about the horrors of the trenches. The arrival of the first American troops in France was greeted enthusiastically but, from about 1916 fewer newsreel stories were concerned with the war. Instead they often focused on the glamorous, the sensational or dramatic aspects of civilian life as audiences became increasingly depressed by the apparently endless struggle in the battle zone; and this was also true of narrative film.[6]

By 1915 the French film industry had to some extent recovered from the traumas of 1914. Films were again in production, but increasingly American films were dominating the box office as Hollywood studios established their own distributors in France. French cinema had lost its pre-eminence and would remain second best for the foreseeable future. Initially French companies produced a number of intensely patriotic features; First National’s ambitious Frontiers of the Heart (1915), based on Victor Margueritte’s (1866–1942) novel of the same name, and The House at the Ferry (1916), for example. While these nationalistic pictures were relatively popular, audiences needed few reminders of the great struggle and looked to cinema for an escape from the realities of everyday life – the shortages, the casualty lists and the constant worry about loved ones. Hence the popularity of American comedies, romance and adventure. Many wondered if the French film industry would ever regain the prestige it once enjoyed; although few went as far as the critic and filmmaker Louis Delluc (1890–1924) who, looking back from 1919 wrote, “I prophesy – we shall see in the future if I am right – that France has no more aptitude for the cinema than for music.”[7]

Yet however grim or distressing the images of wartime footage might be, the newsreels struck an intensely patriotic note – this was no futile or pointless struggle, for on screen the war was a heroic endeavour to repel the invader, regain lost territories and preserve national honour. Whatever the human or material cost, and this was clearly great, there were no uncertainties, no shadow of doubt, that this was a justified and necessary war. Thus newsreels and documentaries provide what we might call the "official" view of the war. It was what encouraged men to go to war and what kept them going to the trenches even in the darkest days. But as the war entered its final phase, and as the real cost began to emerge (1.4 million dead, a million disabled, billions of francs spent, and vast material devastation), the first anti-war film entered production, J’Accuse by ex-army cinematographer Abel Gance (1889–1981). Gance had seen the carnage of war when he filmed the Battle of St. Mihiel, and had been deeply influenced by Under Fire, the 1916 novel by Henri Barbusse (1873–1935) which revealed the appalling suffering of the ordinary soldier on the Western Front. Gance secured the backing of Charles Pathé (1863–1957) for the film and, rather surprisingly, the Army provided considerable assistance. The story centres on a loosely constructed love triangle which the director uses for an often avant-garde approach that switches between reality and the protagonist’s dreams. Originally running for over three hours, Gance had to cut almost half the footage, which inevitably made the film confusing for audiences. The critical response was mixed and while some felt Gance was a genius, others thought J’Accuse was, at best, a failed attempt to capture something of the real nature of the war in a new and appropriate form.[8]

The Post-War Years↑

In the immediate post-war years, the French film industry, like the film industries in most other combatant countries, virtually ignored the war. Partly this was because the subject was unpopular with audiences, who after all, needed no reminders of their suffering and loss; and partly because of economic problems within the French film industry. Cinema was extremely popular, however, throughout the inter-war period only a quarter of films shown in France were French-made. By the mid-1920s most of the old leading studios had gone – Éclair had virtually disappeared, Gaumont had been taken over and Pathé had been bought by the Rumanian Natan Brothers and had become "Pathé-Natan." Many distributors were American-owned and naturally privileged Hollywood’s products.[9] Concerning war films, however, we can identify several phases of production. The first phase, from 1919 until circa 1927 saw the war almost disappear from the screen, perhaps memories were too raw, too painful to recall at that time and needed the passage of time. In a handful of films, like Rose-France (1919) or Koenigsmarck (1923) the war was referred to only in passing. All that changed, however, in 1928 with the tenth anniversary of the Armistice, and the second phase of production which ran until about 1936. The later 1920s witnessed a renewed interest in the war not just in France but throughout Europe: apart from the official histories and commemorations, numerous memoirs and novels written by survivors of the trenches were published and many were adapted for the screen like Erich Maria Remarque’s (1898–1970) All Quiet on the Western Front or Robert Cedric Sherriff’s (1896–1975) play Journey’s End first performed on the London stage and then filmed. Many of these works transcended the national experience and had a universal appeal for anyone who had fought in or who wanted to understand something of the real war. Although the degree varied, most were notable for a considerable cynicism and bitterness about the war, which many felt was unjustified. Most of the novels and films were marked by a deeply anti-war sentiment. For Germany or perhaps even Britain, the war might have been a pointless struggle, but France had, after all been invaded, the war to repel the invader and regain the lost territories could never openly be said to have been pointless. French filmmakers, then, focused on the pity of war, the loss of life, the supreme waste of it all, and the incompetence of those in charge. Pierre Sorlin rightly suggests that most of the French films made between the wars reflect the "pathetic" mood that hung over the Republic, a tone perhaps first suggested by J’Accuse – a tone it is tempting to think that contributed to the sense of hopelessness and apathy that led to the political and military collapse in 1940. Or perhaps that is to read these films from a position of hindsight.[10]

This middle phase of French production, however, included a dozen or so films, some of which dealt with the war only obliquely but others like Verdun, Visions of History (1928/1931), The Doomed Battalion and Wooden Crosses (both 1931), confronted the combat experience head on. The docu-drama Verdun was particularly interesting and was the major French contribution to a European interest in using docu-drama to reconstruct aspects of the war. The style originated with Harry Bruce Woolfe (1880–1965) of British Instructional Films (BIF) in 1921. Wanting to celebrate the Battle of Jutland, Woolfe used actual footage, models, animation and reconstructions to tell the story of the Battle. Surprisingly popular with audiences, this led Woolfe to make a further five docu-dramas about the war by 1927.[11]Verdun was the work of the independent filmmaker Leon Poirier (1884–1968). The director’s intention was to accurately reconstruct the battle to show the "obscene folly of war" but not to apportion blame or demonize the enemy in the hope that it might dissuade future generations from seeking to settle differences by war. Again surprisingly, the French Army initially provided considerable resources for Poirier but later withdrew. Nevertheless, it is, according to critic James Travers, a "stunningly realized film with intellectual and emotional impact...An illuminating insight into one of the bloodiest battles in human history."[12]

Interestingly, two further films in this docu-drama style were made shortly afterwards in Germany: Douaumont (1931), an examination of the fighting at Verdun from the German perspective; and Tannenberg (1932), which looked at the German victory over the Russians early in the war. Both made use of newsreel footage and reconstruction and both, like Poirer’s Verdun, employed German and French veterans of the battle in a spirit of reconciliation.

1929 to 1932 was a period in which the Great War suddenly erupted onto cinema screens in a series of large-scale, powerful and dramatic narrative films – from England came Tell England, Anthony Asquith (1902–1968) and Journey’s End, James Whale (1889–1957); from Hollywood, Lewis Milestone’s (1895–1980) All Quiet on the Western Front, and from Weimar Germany Georg W. Pabst’s (1885–1967) Westfront 1918. The French contribution to this sequence was The Doomed Battalion and Wooden Crosses, Raymond Bernard (1891–1977), based on the novel by Roland Dorgelès (1885–1973), and arguably the most powerful French combat film of the period. Wooden Crosses tells the story of two soldiers, Breval (a banker) and the young student Demachy, who move from fervent patriotism to bitter disillusionment as the war continues. There are some powerful episodes in the film like the unbearably tense scene where German sappers tunnel under the French trenches and the battle sequences where the soldiers have to carry out a raid on an enemy trench. So effective was the film that the Fox Company bought the film for release in America.

The final phase of production began in the late 1930s when it seemed likely that another European war would darken the horizon. Some filmmakers optimistically thought that they might use the memory of 1914 to sustain the peace, to warn against the horrors of another conflict. Of the major films made at this time Jean Renoir’s (1894–1979) much-admired La Grand Illusion was released in 1937, and the following year Gance made a sound version of J’Accuse. La Grande Illusion was informed by the director’s own experience of war - Renoir had served initially in the cavalry but after being wounded was transferred to the air service. The film was loosely based on the experiences of an aristocratic staff officer that Renoir had first met during the war. The film, mostly set in a prison camp is an examination of the themes of duty, honour and sacrifice, and serves to show the futility of war. The disappointing sound version of J’Accuse bears little resemblance to the original, apart from the famous ‘return of the dead’ sequence. Here, the protagonist is obsessed by the idea that another war is coming but frustrated that he cannot make others realise the danger. Eventually, however, the politicians make war illegal – a clichéd and naïve view that was less than enthusiastically received by many critics.

The Second World War and After↑

The German occupation of France in 1940 imposed strict controls on the film industry – only films sanctioned by the authorities could be made and political films were not on the agenda – there were to be no reminders of the German defeat in 1918. After the Liberation in 1944, the Great War seemed remote to many French people, almost an irrelevance after the catastrophe of 1940, and the re-emerging film industry made only two minor films about the Great War before 1963 – Devil in the Flesh (1947) and Shot at Dawn (1950). The fiftieth anniversary of 1914, however, did re-kindle some interest in the Great War and it became a source of interest not only for historians but for some writers and filmmakers. Thomas the Imposter (1965) and King of Hearts (1966) were perhaps the most interesting films which emerged at that time. King of Hearts is particularly interesting as it likens war to the behavior of lunatics. The often farcical elements bear some resemblance to Richard Attenborough’s polemical film Oh! What a Lovely War. I think we should probably see King of Hearts as very much part of an international response by filmmakers to the horrors not just of the World Wars but to the more recent conflicts in Indo-China, Algeria and elsewhere.

Writing over a decade ago, the historian Pierre Sorlin suggested that while the forty or so feature films about the Great War made in France since 1918 might suggest an ongoing engagement with the conflict, the filmic memory has been silent when it comes to some aspects of the War. "It is well-known that veterans had terrible difficulty re-entering civilian life, all the more when they were disfigured or severely disabled...They [the films] did not show [these problems nor] the challenges to those who had been mobilized and those who had lost their loved ones."[13] Since that essay was published, more recent films have powerfully examined some of those previously "silent memories": the trauma of disfigurement in Francois Dupeyron’s Officers’ Ward (2001); the loss of a loved-one in Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s A Very Long Engagement in 2004, and shell-shock and long-term hospitalization in Fragments of Antonin (2006), Gabriel le Bomin.

Conclusion↑

As we enter the age of post-memory, the cinematic image of the Great War will assume even greater importance, but what will be the dominant image of the war for those future audiences? In common with most other European filmmakers, French cineastes, since at least the mid-1920s, have adopted an interpretation of the War established from the literary accounts of the survivors of the trenches like Barbusse and Chevallier[14], who wrote about their experiences in such bitter terms; a view which sees a tragic and horrible experience brought about by the twin evils of patriotism and militarism, and which was shared equally by the brotherhood of the trenches, friend and foe alike. One of the most interesting recent films is Christian Carion’s Joyeux Noël (2005). This begins with an introduction of the children of 1914 in France, Britain and Germany reciting hymns of hatred for their enemies and then concentrates on what might have happened in one sector during the 1914 Christmas truce on the Western Front when the major combatants unilaterally ceased fire and met in No Man’s Land.[15] Then comes the realization that they are all suffering and that no one wanted war, nor did they really know why they were fighting. What is really interesting about the film, however, is that this was a French/British/German/Belgian/Rumanian co-production with a pan-European cast and crew – a European, not simply a nationalistic, filmic response to that particular memory of the Great War and remarkably similar in tone to those films which originated in the 1920s. With centenary commemorations well under way perhaps it is time to consider just how we film our memory of that war?

Michael Paris, University of Central Lancashire

Filmography↑

All Quiet on the Western Front (United States, 1930, Lewis Milestone)

Battle of Jutland (Great Britain, 1921, Harry Bruce Woolfe)

Devil in the Flesh (France, 1947, Claude Autant-Lara)

Douaumont (Germany, 1931, Heinz Paul)

Frontiers of the Heart (France, 1915)

Hearts of the World (United States, 1918, David Wark Griffiths)

House of the Ferry (France, 1917)

J’Accuse (France, 1918, Abel Gance)

J’Accuse (France, 1938, Abel Gance)

Journey’s End (Great Britain/United States, 1930, James Whale)

King of Hearts (France/Italy, 1966, Philippe de Broca)

Koenigsmarck (France, 1923, Leonce Perret)

La Grand Illusion (France, 1937, Jean Renoir)

Oh! What a Lovely War (Great Britain, 1969, Richard Attenborough)

Rose-France (France, 1919, Marcel L’Herbier)

Shot at Dawn (France, 1950, Gilles Grangier)

Tannenberg (Germany, 1932, Heinz Paul)

The Doomed Battalion (France, 1931, Cyril Gardner and Karl Hartl)

The French Offensive on the Somme (France, 1916, Army Cinema Service)

Thomas the Imposter (France, 1964, Georges Franju)

Verdun – Visions of History (France, 1928, Leon Poirier)

Westfront 1918 ["Western Front 1918"] (Germany, 1930, Georg Wilhelm Pabst)

Wooden Crosses (France, 1931, Raymond Bernard)

Section Editor: Nicolas Beaupré

Notes

- ↑ This particular report is on the Open University compilation video A 318 War, Peace and Social Change.

- ↑ See Becker, Jean Jacques: 1914: Comment les Francais sont entres dans la guerre, Paris 1977.

- ↑ See Sorlin, Pierre: "French Newsreels of the First World War", in: Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, 24:4 (2004), pp. 507 – 515.

- ↑ Quoted in Kelly, Andrew: Cinema and the Great War, London 1997, p. 25.

- ↑ Quoted in Kelly, Andrew: Cinema and the Great War, London 1997, p. 25. On Grffiths’ filming on the Western Front see, Brown, Karl: Adventures with D.W. Griffiths, London 1988. Hearts of the World was finally released in 1919, too late to have any influence on Allied morale.

- ↑ Sorlin, "French Newsreels", pp. 508-509. A catalogue of the films made by the Army Cinematographic Section is available, see Lemaire, Francoise: Les Films Militaires Francais de la Premiere Guerre Mondiale: Catalogue des Films Muets d’Actualite, Paris 1997.

- ↑ Quoted in Bardeche, Maurice/Brasillach, Robert: History of the Film, London 1945, p.134.

- ↑ On Gance see, Veray, Laurent: "Abel Gance, cinéaste à l’œuvre cicatricielle", 1895. Revue de l’association française de recherche sur l’histoire du cinéma, dossier ‘ Abel Gance. Nouveaux regard’, 31 (2000), pp. 19-52; Veray, Laurent: “J’accuse, un film conforme aux aspirations de Charles Pathé et à l’air du temps” 1895. Revue de l’association française de recherche sur l’histoire du cinéma, dossier "Abel Gance. Nouveaux regard" 21 (1995), pp. 93-123.

- ↑ Ibid, pp. 225-226.

- ↑ Sorlin, Pierre: "France: the Silent Memory", in Paris, Michael (ed.): The First World War and Popular Cinema, Edinburgh 1999, p. 128.

- ↑ See Paris, Michael: "Enduring Heroes: British Feature Films and the First World War, 1919-1997", in Ibid, pp. 51 – 73.

- ↑ Travers, James: "Verdun – Visions of History", filmsdeFrance.com (accessed 6 June 2013). A complete and newly restored print of Poirer’s film is now available from the Cinematheque de Toulouse.

- ↑ Sorlin, "France: the Silent Memory", p, 124.

- ↑ Barbusse, Henri: Under Fire, Chevallier, Garielle: Fear, Paris 1930.

- ↑ Joyeux Noel found a mixed reception see, Beaupre, Nicolas: Sale guerre et bons sentiments’, Images et Sons Vingtième Siècle, in : Revue d’histoire 90 (2006), pp.201-202.

Selected Bibliography

- Armes, Roy: French cinema, New York 1985: Oxford University Press.

- Bénard da Costa, João: Histórias do Cinema Português (Histories of Portuguese cinema), Lisbon 1991: Imprensa Nacional.

- Dibbets, Karel / Hogenkamp, Bert (eds.): Film and the First World War, Amsterdam 1995: Amsterdam University Press.

- Kelly, Andrew: Cinema and the Great War, London; New York 1997: Routledge.

- Kester, Bernadette: Film front Weimar. Representations of the First World War in german films of the Weimar period, 1919-1933, Amsterdam 2003: Amsterdam University Press.

- N.N.: Regulamento da Secção Fotográfica e Cinematográfica do Exército (Regulation of the army’s photography and film section): Ordem do Exército (Army’s order), volume 6, 1918, pp. 379-385.

- Paris, Michael (ed.): The First World War and popular cinema. 1914 to the present, New Brunswick 2000: Rutgers University Press.

- Puget, Clément: Verdun... de Léon Poirier, in: 1895. Mille huit cent quatre-vingt-quinze. Revue de l'association française de recherche sur l'histoire du cinéma 45, 26 February 2007, pp. 5-29, doi:10.4000/1895.862.

- Puget, Clément: Verdun et le cinéma, Paris 2014: Nouveau Monde.

- Sorlin, Pierre: Film and the Great War, in: Horne, John (ed.): A companion to World War I, Chichester; Malden 2010: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Sorlin, Pierre: The French newsreels of the First World War, in: Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 24/4, 2004, pp. 507-515.

- Véray, Laurent: Les films d'actualité français de la Grande Guerre, Paris 1995: SIRPA; AFRHC.

- Véray, Laurent: La Grande guerre au cinéma. De la gloire à la mémoire, Paris 2008: Ramsay.