Faysal and the Arab Awakening↑

Faysal I, King of Iraq (1885-1933), the third son of Husayn ibn Ali, King of Hejaz (c.1853-1931) and Sharif of Mecca, was initially skeptical of the feasibility of an anti-Ottoman rebellion and the possibility that the Arab Movement could lend significant support to an armed uprising in the Hejaz. It was his elder brother Abdullah, King of Jordan (1882-1951) who was the driving force behind the Hashemite’s decision for a revolt involving the Arab cause.

Nonetheless, it was Faysal’s stopover in Damascus in the spring of 1915, and his meetings with Arabists there, that revealed to the Hashemites the scale of discontent with Ottoman rule in Greater Syria. By then, the Sharif of Mecca and his sons were in possession of hard evidence of the Committee of Union and Progress’ (CUP) intention to replace Husayn as Amir in Mecca with ‘Ali Haydar (1866-1935), a member of the rival Hashemite clan of the Dhawi Zeid. On his subsequent journey to Istanbul, Faysal failed to obtain satisfactory guarantees of his father’s position from the CUP, despite delivering promises to support the Ottoman campaign in Sinai.

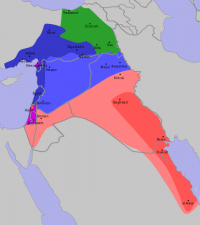

The gulf between the Hashemites and the CUP now seemed unbridgeable. In May 1916, Faysal signed the “Damascus Protocol” with members of the Arabist secret societies al-Fatat (the largely Syrian and, in its majority, civilian society of the “Young Arabs”) and al-‘Ahd (“the Covenant,” a predominantly Iraqi organization of Arab officers serving in the Ottoman military). The agreement committed the Hashemites and their Arabist allies to an anti-Ottoman uprising, in cooperation with Britain, in return for pledges of Arab independence. The Protocol formed the basis of the Sharif Husayn’s claims for an expanded Arab Kingdom during the (in)famous Husayn-McMahon correspondence that presaged the launching of the Arab Revolt in June 1916.

Faysal and the Arab Revolt↑

Once the revolt broke out, Faysal led an abortive assault on Medina before taking command of Husayn’s “Northern Army” (his oldest brother Ali was put at the head of the “Southern Army,” and Abdullah was in charge of the “Eastern Army” that took over the siege of Medina from Faysal). The Northern Army was to play the key role in the evolution of the revolt as it spearheaded the Arab advance into Syria and undertook the vast majority of the guerilla operations on the right flank of the British Imperial forces advancing from Egypt under Edmund Allenby’s (1861-1936) command. The Northern Army included a substantial regular force recruited from former Ottoman army officers and soldiers sympathetic to Arab national aims. Most accounts agree that Faysal proved adept at gaining the loyalty of these largely Iraqi and Syrian troops, while also holding together the shifting tribal coalitions necessary for the recruitment of the Bedouin irregulars who formed the mainstay of the Hashemite Army.

Faysal also proved himself to be an effective, if not spectacularly successful, war leader. The operations undertaken by his forces in the highlands and coastal plains to the west of Medina in the winter and spring of 1916-1917, and the campaign that culminated in the occupation of the ports of Rabegh and Yanbu‘ (July 1916) neutralized the Ottoman forces concentrated in Medina, forcing its garrison to defend what was in effect an extended right flank stretching northwards to Ma‘an. Once the Northern Army occupied the port of Wajh with British naval support in January 1917, the remaining Ottoman forces in the northern Hejaz were effectively isolated and their supply lines – based above all on the highly vulnerable Hejaz railway – became increasingly difficult to maintain.

Faysal’s occupation of Wajh also provided a platform for contacting the Syrian tribes, and the Huwaytat in particular. Elements from the Tawayha and Njadat sections of the Huwaytat, led by the renowned war leader Auda Abu Tayih (1874-1924), were instrumental in the capture of Aqaba in July 1917. The forces of the revolt under Faysal’s youngest brother, Zayd ibn al-Husayn, Prince of Hejaz (1898-1970), moved into the Shirah mountains east of Ma‘an, defeating an Ottoman counterattack at the Battle of Tafilah (January 1918), while regular Arab forces under the command of Ja‘far al-‘Askari (1885-1936) made abortive assaults on Ma‘an in April 1918. These developments allowed the forces of the revolt to have access to the supply routes of such major Syrian Bedouin confederacies as the Ruwallah, and opened the way for a campaign of enticement aimed at extending the Hashemite’s ladder of tribal support northwards into al-Balqa’ and the Hawran. Yet, despite the success of its guerilla attacks on Ottoman supply lines, Faysal’s army failed to progress north of the Wadi al-Hasa, or to offer effective support for the two Trans-Jordan raids undertaken by Allenby in the spring of 1918 (these temporarily occupied al-Salt in March/April 1918). It was only Allenby’s victory at Megiddo (September 1918), and the subsequent Ottoman collapse in October and November 1918, that opened the way for Faysal's triumphal entry into Damascus on 3 October 1918.

Postwar↑

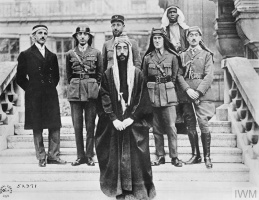

With British support, Faysal established an Arab national government in Damascus. Its leading cadres were drawn from the Arabist secret societies and its Congresses dominated by a motley coalition of tribal leaders and former Ottoman officers. Viewed by Arab nationalists as encompassing Greater Syria, Faysal’s “kingdom” was only recognized as the administrator of “Occupied Enemy Territory East” by the Great Powers. Once the latter had agreed upon the division of the Arab provinces of the Ottoman Empire at St. Remo (April 1920), Faysal’s twenty-two-month rule in Damascus (October 1918‑July 1920) was brought to an end by France’s occupation of the Syrian interior.

In London, at the time of the 1921 Cairo Conference that decided the fate of Britain’s new mandate possessions in the Arab East, Faysal was installed as king of Iraq in August 1921 under imperial tutelage as part of a wider “Sharifian Solution” (his brother Abdullah was installed as Emir in Trans-Jordan at the same time) to the problem of maintaining order in the Fertile Crescent. Despite having been foisted onto the Iraqi throne by colonial machinations, Faysal was able to maintain a credible distance between himself and the British. Eventually, he was successful in guiding Iraq to early – if still constrained – independence in October 1932.

Tariq Moraiwed Tell, American University of Beirut

Section Editor: Abdul Rahim Abu-Husayn

Selected Bibliography

- Allawi, Ali A.: Faisal I of Iraq, New Haven 2014: Yale University Press.

- Antonius, George: The Arab awaking. The story of the Arab national movement, London 1938: H. Hamilton.

- Erskine, Beatrice: King Faisal of Iraq. An authorised and authentic study, London 1933: Hutchinson.

- Masalha, Nur-Eldeen: King Faisal I of Iraq. A study of his political leadership, 1921-1933, thesis, London 1988: University of London.

- Mohamad, Faysal: Faysal ibn Al-Husayn and Britain. The uneasy alliance, thesis, Toronto 1996: University of Toronto.