War Volunteer on the Western Front↑

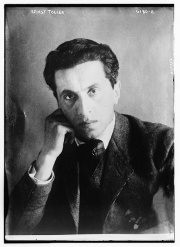

Ernst Toller (1893-1939) was born into an observant Jewish family from Samotschin (Szamocin) in the Prussian province of Posen. In August 1914, he voluntarily enlisted for war service in a Bavarian heavy artillery regiment. Having felt treated as a second-class citizen because of his Jewish background, he hoped that the war would offer an opportunity for full-fledged social integration. In his autobiography, he writes that Wilhelm II, German Emperor’s (1859-1941) call for a Burgfrieden (civil truce), which envisioned a true community of Germans, had great impact on him.[1]

His war experience was disenchanting and traumatic. Posted close to Verdun, Toller experienced front warfare and its horror first hand. In the spring of 1916, he physically collapsed and was declared unfit for war service in January 1917.

Rethinking the Front Experience↑

Released from his duties in the summer of 1916, Toller settled in Munich, where he attended university. He established friendships with other war veterans, such as the sculptor Kurt Kroner (1885-1929) and the students Eugen Roth (1895-1976) and Erich Trummler (1891-1983), and tried to make sense of his war experience. He embraced a tolerant universalism and, influenced by a literary and activist Expressionism, a belief in the need for humanity’s spiritual transformation. By the summer of 1917, he had started to write his first drama, Die Wandlung (The Transformation, 1919). The play is about a war volunteer’s transformation from a nationalist warrior into a humanist pacifist.

In the early fall of 1917, Toller attended the second of three conferences at Burg Lauenstein in Upper Franconia, organized by the publisher Eugen Diederichs (1867-1930), to rethink the role of the cultural establishment in wartime Germany. There he met the poet Richard Dehmel (1863-1920), the painter Carl E. Uphoff (1885-1971), and the sociologist Max Weber (1864-1920). Toller would later write that the lack of intellectual leadership during this meeting convinced him that “we, the young ones” had to act on their own in their quest for new spiritual values.[2]

Anti-War Activism↑

In the fall of 1917, Toller moved to Heidelberg to attend university. He joined Max Weber’s famous Sunday Circle and a group of students around the Austrian Socialist and women’s rights activist Käthe Pick (1895-1942), who took a critical stance against the war. Responding to increasingly radical forms of nationalism and, more concretely, to the harassment of the pacifist professor Wilhelm Friedrich Foerster (1869-1966) by völkisch students in Munich, Toller sought to transform Pick’s group into a Students’ League that advocated a tolerant, humanist universalism. He called for a radical change in mind-set, taking inspiration from Gustav Landauer’s (1870-1919) Aufruf zum Sozialismus (Call for Socialism, 1911), which provided an "anarcho-socialist" perspective on the organisation of human society. Landauer’s book also influenced Die Wandlung, which Toller had more or less finished by the end of that year. Alarmed by a polemic between Toller and his critics in the press, Heidelberg professors publicly distanced themselves from Toller in December 1917, while the General Command of the Baden Army Corps expelled the Austrian members of the League from Germany.

Toller fled to Berlin, where he met, in January 1918, Kurt Eisner (1867-1919), one of the founders of the pacifist Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD). Afraid that the army might suspend his release from war service because of his Heidelberg actions, Toller decided to leave for Munich a few weeks later to visit the headquarters of the First Bavarian Army Corps, of which his regiment was part. He also wanted to finish his studies in that city and to seek support for his League. Shortly after his arrival, Eisner organized mass meetings and strikes in Munich calling for democracy and peace. Toller’s involvement in these events led to his imprisonment from February to April 1918.

The 1918/19 Revolution↑

When Eisner proclaimed Bavaria a republic on 7 November 1918 in Munich (two days before the German Republic was proclaimed in Berlin), Toller was at his mother’s home in Landsberg an der Warthe (Gorzów Wielkopolski). Later that month, he returned to Munich, where he began to support the workers’ and soldiers’ councils (Räte). These councils had emerged everywhere in Germany since the Kiel mutiny in late October and offered a vision of a direct, participatory democracy. They lost political strength in December 1918, when the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD) voted in favour of a parliamentary system, i.e. against the council system, and the governing national coalition between the SPD and the USPD broke up. However, after Eisner’s assassination in February 1919, advocates of the council system in Bavaria proclaimed a Council Republic (Räterepublik) in April 1919. In a tumultuous meeting, Toller, a member of the Central Workers’ Council (Zentralarbeiterrat) since late 1918 and Chairman of the Munich USPD since March, became Chairman of the Central Workers’ Council. This catapulted him to the official head of the newly founded Council Republic. Toller did not develop a clear political program in 1918/19, but continued to advocate an anarchically inclined idea of democracy and humanist socialism.

The Bavarian Räterepublik under Toller’s leadership was short-lived. Only one week after its proclamation, Communists took control and sought to transform the fledgling state into a Russian-style Soviet Republic. His critique of these actions notwithstanding, Toller accepted a position as commander of the troops that defended the Communist-ruled Republic against the Social Democrat Berlin government, which had declared war on the Bavarian Räterepublik. In spite of a victory, the Council Republic was soon defeated by General Wilhelm Groener (1867-1939) with the support of various Freikorps units. Toller was sentenced to five years in prison for high treason.

Pacifism and the Memory of the First World War↑

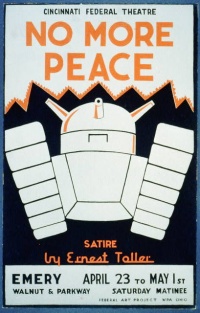

Toller distanced himself from party politics after the Bavarian episode, but remained politically engaged. In the 1920s, he became a very successful playwright. His plays took a pacifist and cosmopolitan stance, and expressed a commitment to humanist, non-party-bound socialism. He also addressed the ills of the First World War. For example, in Der deutsche Hinkemann (The German Hinkemann, 1923) he took up the themes of male sexual impotency and the destruction of family life during and after the war. Due to his opposition to Nazi politics and his Jewish origins, Toller was forced into exile in 1933. In May 1939, he committed suicide in New York.

Steven Schouten, University of Amsterdam

Section Editor: Frederik Schulze

Notes

Selected Bibliography

- Dove, Richard: He was a German. A biography of Ernst Toller, London 1990: Libris.

- Hempel-Küter, Christa / Müller, Hans-Harold: Ernst Toller. Auf der Suche nach dem geistigen Führer. Ein Beitrag zur Rekonstruktion der “Politisierung” der literarischen Intelligenz im Ersten Weltkrieg: Internationales Archiv für Sozialgeschichte der deutsche Literatur. Literatur, Politik und soziale Prozesse. Studien zur deutschen Literatur von der Aufklärung bis zur Weimarer Republik, Sonderheft 8, Tübingen 1997: Niemeyer, pp. 78-106.

- Schouten, Frederik Steven Louis: Ernst Toller. An intellectual youth biography, 1893-1918, thesis, Florence 2007: European University Institute.

- Toller, Ernst, Distl, Dieter et al (ed.): Sämtliche Werke. Kritische Ausgabe, Göttingen 2015: Wallstein Verlag.

- Toller, Ernst, Spalek, John M. / Frühwald, Wolfgang (eds.): Gesammelte Werke, Frankfurt a. M. 1978: Carl Hanser.