The Dunsterforce Mission↑

By war’s end, 890,000 British imperial soldiers had served in the Middle Eastern theatre, suffering roughly 95,000 casualties, with a financial cost of £350 million.[1] It was into this muddled, secondary or “side-show” theatre of war that Dunsterforce, an undersized, elite, secret unit made up of 450 choice soldiers of “highly individualistic characters … of the do or die type” from across the empire, was deployed in 1918 to seize the oil installations at Baku on the western shore of the Caspian Sea.[2] Oil progressively became more important in British strategic thought and action, most notably in 1918, and into the peace negotiations. This mission was officially sanctioned in December 1917 as the British Military Mission to the Caucasus — commonly known as Dunsterforce, after its commander Major-General Lionel C. Dunsterville (1865-1946).

Given the turmoil created by the various ethnic groups and factions operating in the Caucasus region, it was necessary for the commander of this force to be familiar with the capricious state of affairs. Dunsterville met the criteria, as he was fluent in Urdu, Punjabi, Pashtu, Persian, Russian, German, French and Chinese.[3] By this time, Dunsterville was already a legendary figure thanks to his childhood friend Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936), who immortalized him as the bold leader “Stalky” in the boyhood picaresque adventure tale Stalky and Co. (1899).[4] Dunsterville acknowledged that “Stalky & Co. is a work of fiction, and not a historical record. Stalky himself was never quite so clever as portrayed in the book.”[5]

Prior to the war, Dunsterville had served predominantly in the backwaters of the British Empire, and in 1915 he was posted to the north-west frontier of India. Here Dunsterville remained until his selection, in December 1917, to lead the force that would take his name, with the mission to:

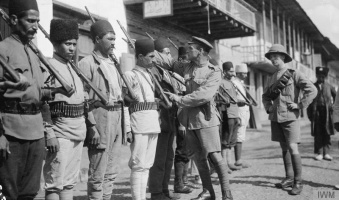

Major-General Dunsterville’s first task was to organize a coherent body of resistance out of the miscellaneous, and often mutually hostile, groups of anti-Bolshevik Russians, anti-Ottoman Georgians, Armenians, and Assyrians spread across the Caucasus region.[7] Once established, the primary mission of his collective force was to guard the Transcaucasian Railway line from the Russian cities of Baku to Tbilisi, in addition to protecting natural resources, including the oil fields at Baku, from the Ottomans (and the Germans), while defending the 51 percent stake in the Anglo-Persian Oil Company owned by the British government. It was also hoped that Dunsterville could aid in the establishment and maintenance of an independent group of nations — Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan — although this was a secondary objective in order to facilitate the application of the primary concern —i.e. oil. Another reason for occupying Baku was to prevent the enemy route to India. The Berlin-Batum-Baku-Bukhara line was a more dangerous enemy route to the Indian frontier than was Wilhelm II, German Emperor’s (1859-1941) envisioned Berlin-to-Baghdad railway.

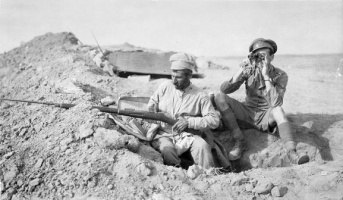

The conditions and geography of the Middle East and Caucasus in which Dunsterforce traversed and fought were unrelenting and austere. Marches of ten to thirty miles per day under blistering temperatures topping 50C or plummeting to -40C in mountain passes exceeding 10,000 feet became routine. They were often treated as unwelcome strangers in lands wracked by drought, famine, genocide, and civil war. Isolated from immediate reinforcements or a reliable supply-line, the men of Dunsterforce trudged forward from Basra to Baghdad to Baku. They were ostensibly wandering orphans of the war, and dubbed by one participant as “no man’s child.”[8]

Battle of Baku↑

Along the way, they encountered German spies, rescued American missionaries, ministered to starving Persians and refugee Armenians and Assyrians, and built roads to alleviate famine and the passage of Christian refugees fleeing ethnic annihilation. The soldiers of Dunsterforce battled Ottoman forces, the “Savage Division” of jihadist mercenaries, as well as Kurdish and Persian Jangali guerrillas. They fought alongside Bolshevik soldiers of the Red Army, volunteer Armenian units, disavowed Russian Cossacks, and flew Serbian and Bolshevik flags all in a failed attempt to protect Baku’s precious oil from Ottoman or German appropriation. The Battle of Baku began on 26 August 1918, and ended with the evacuation of Dunsterforce on 14 September. Although fighting a determined and well-orchestrated rear-guard action, the vastly outnumbered and underequipped soldiers of Dunsterforce were forced to concede Baku and its prized petroleum resources to the Ottomans.

Many members of Dunsterforce outwardly criticized their commander and the mission. Lieutenant-Colonel John W. Warden (1871-1942), who by now was calling the mission “Dunsterfarce,” sardonically quipped that:

Others, including British Prime Minister David Lloyd George (1863-1945), believed that Dunsterforce kept the Ottomans and Germans from acquiring much-needed oil for six crucial weeks in August and September while the war with Germany was decided on the Western Front, and victory over the Ottomans was secured in Mesopotamia, Palestine, and on the Salonika/Bulgarian front.

Timothy C. Winegard, Colorado Mesa University

Section Editor: Erol Ülker

Notes

- ↑ Moberly, F.J.: The campaign in Mesopotamia, 1914-1918, vol. IV, London 1923, p. 331.

- ↑ Library and Archives Canada (LAC) MG30 E192, LCol J.W. Warden File-Diary 1918-1919.

- ↑ Dunsterville, Lionel: Stalky’s reminiscences, London 1928, pp. 68, 178.

- ↑ Kipling, Rudyard: Stalky & Co., London 1899.

- ↑ Dunsterville, Stalky’s reminiscences, p. 25.

- ↑ LAC RG24, Vol. 1840, File GAQ 10-28: The Dunsterforce (Baghdad Mission). Mesopotamian Expeditionary Force, 1918.

- ↑ These refer to ethnic groups that were at this time, in most cases, not associated with an actual country of the same name. They were part of the Ottoman or Russian Empires or undefined border regions within the Middle East.

- ↑ Warden, J.W.: Diary entry, 7 March 1918.

- ↑ Warden, J.W.: Diary entry, 15 September 1918.

Selected Bibliography

- Donohoe, Martin Henry: With the Persian expedition, London 1919: E. Arnold.

- Dunsterville, Lionel Charles: The adventures of Dunsterforce, London 1920: Edward Arnold.

- Rawlinson, Alfred E. J.: Adventures in the Near East, 1918-1922, London 1923: Melrose.

- Stewart, Alan: Persian expedition. The Australians in Dunsterforce, 1918, Loftus 2006: Australian Military History Publications.

- Winegard, Timothy C.: The first world oil war, Toronto; Buffalo; London 2016: University of Toronto Press.