Introduction↑

Norway gained its independence as a state only nine years prior to the outbreak of the First World War in 1914. The separation from Sweden in 1905 was peaceful and was followed in 1907 by an agreement signed by Russia, Germany, France, and Great Britain to guarantee Norway’s independence. Sensitive to its status as a small state on the outskirts of Europe, the Norwegian government pursued neutrality in the years before the war and declared the country neutral on 4 August 1914. A few days later, the Norwegian and Swedish governments declared their intention not to go to war against each other and eased fears that the two countries would end up on different sides of the conflict. Further signalling of neutrality came in December 1914, when the kings of Denmark, Sweden, and Norway met in Malmø.[1] At home, the Norwegian government’s declaration of neutrality was met with almost universal support from both political opponents and society. Underneath this apparent unity, however, there were both ideological and social tensions that would come to the surface as the war progressed.

Defending Neutrality↑

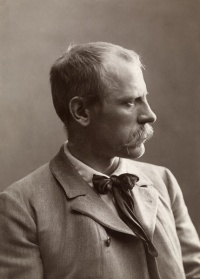

On 2 August 1914, the Norwegian government ordered the mobilization of the country’s navy and the reserve forces of the coastal defence installations. Prime Minister Gunnar Knudsen (1848-1928), who was also minister of agriculture, ordered a stop of the export of grain, flour, potatoes, coal, and other essential raw materials. Two days later, as Britain declared war on Germany, Norway issued a formal declaration of neutrality to the belligerent nations. The next day, the Norwegian army mobilized the bulk of its forces in order to establish a neutrality watch (nøytralitetsvakt).

Prime Minister Knudsen and his Liberal Party (Venstre) had been in government since the 1912 election. Knudsen was a traditional liberal politician who believed in small government and free-market capitalism. He came from a background in shipping and trade across the North Sea, which had made him favour Britain over Germany. His pro-British inclination was not a secret, but he made every effort to keep Norway on a neutral course.[2] The Knudsen government’s foreign policy of neutrality found little, if any, opposition in parliament or Norwegian society. In many respects, the war caused party politics to move into the background, at least in the early war years. The outbreak of war in 1914, however, did result in demands for the creation of a coalition government. Conservative-inclined newspapers eagerly called for Knudsen’s resignation and the establishment of a wartime coalition cabinet with representatives from both the Conservative Party (Høyre) and the Liberal Party (Venstre). This idea even found support within Knudsen’s own party, with former Prime Minister Wollert Konow (1845-1924) being an important supporter. Konow’s prime concern was how Norway should and could retain its close relationship to Britain if neutrality should fail. He publicly stated that the country could not afford to have Britain as its enemy.[3] Bernhard Hanssen (1864-1939), a member of parliament for the Liberals and a noted peace activist prior to the war, was another voice that also underlined the importance of keeping the peace with the power that both controlled the sea and Norway’s access to it.[4] Demands for the establishment of a coalition government were repeated through the war, but Knudsen refused all of them and the Liberal Party retained power until 1920.

The outbreak of war was one reason for the Conservative Party to demand a coalition government; the other reason was that they did not trust Knudsen as prime minister. However, they were willing to enter into a Burgfrieden and put aside differences until the end of the war. One reason for this approach was an internal power struggle and a lack of coordination within the party itself. Knudsen and Venstre’s election victory in 1912 had caused infighting and finger-pointing among the Conservatives.[5] Another election defeat for the party in 1915 further strengthened these internal struggles, undermining any criticism of the Knudsen government.

Despite Prime Minister Knudsen’s majority in parliament and lack of willingness to enter into a coalition government, he recognised the fact that the government needed to play a far more unifying and active role than previous administrations. Consequently, he created several committees intended to deal with a number of issues such as unemployment, supplies, and war insurance for the merchant fleet. The committees had extensive executive power and constitutional questions regarding their legality became an issue, but parliament accepted them despite some reservation. In part, this acceptance was caused by Knudsen’s appointment of both political allies and opponents, experts and business leaders to the different committees: for example, the future Labour Prime Minister Christopher Hornsrud (1859-1960) and Ole O. Lian (1868-1925), the leader of the Norwegian Confederation of Trade Unions. The inclusion of these two prominent labour representatives and other political opponents was a nod to the importance of the labour movement, which was itself not a force in parliament.[6]

The Conservatives and the Liberal Party dominated Norwegian parliamentary politics at the outbreak of war in 1914. The Norwegian labour movement was firmly established, but its political wing, the Labour Party (Det norske Arbeiderpartiet), founded in 1887, struggled to establish itself as a major national party. Its breakthrough had come in the 1912 election, when it more than doubled its number of members of parliament, from eleven to twenty-three. In parliament, they were supporters of neutrality and supported the extraordinary measures taken by the Knudsen government in 1914. This support even extended to extra funding for the Norwegian military, a break from their earlier anti-militaristic policy. While the leadership of the Labour Party supported the government, a smaller, more radical and anti-militaristic group known as the trade union opposition (fagopposisjonen) and under the leadership of Martin Tranmæl (1879-1967) found it more difficult to support the Knudsen government’s policies. This radical group had a growing influence on the labour movement, in some parts helped by the Knudsen government passing laws against anti-militaristic propaganda in the autumn of 1915, but also due to the Russian Revolution in 1917.

“Jobbetid” and “Dyrtid”↑

The First World War brought both benefits and hardship to the Norwegian economy. In the first two years of the war, rising exports to the belligerent nations and ever-increasing freight prices lay the foundation for booming economic growth. Ship-owners and companies made large fortunes, and even Norwegian agriculture witnessed a sharp rise in profits. Inflation and the cost of living was high, but wages also rose and unemployment was relatively low in most sectors. Norway was an attractive trading partner for both sides of the conflict and could offer both natural resources vital to the production of arms and a large fishing industry. As a result, the period was given the labels “jobbetid” (direct translation: “worktime”) and “dyrtid” (direct translation: “expensive times”).[7]

As a neutral, however, Norwegian politicians and business leaders would have to navigate between the belligerent states and not be seen to favour one over the other. At the same time, both Germany and Britain did attempt to exclude the other side from trading with Norway. The Knudsen government responded to these challenges by allowing representatives from each individual business sector to negotiate separate deals with British and German authorities. The central role played by industry and commerce in these negotiations has been termed the diplomacy of business by the Norwegian historian Olav Riste (1933-2015).[8] Indeed, a booming wartime economy was one of the main factors that helped Prime Minister Knudsen and the Liberal Party to secure victory in the 1915 election. At the same time, both the Conservatives and Labour experienced reversals.

From 1916, however, the import of both essential raw materials and consumer goods became more difficult as the war escalated. At the same time, both Germany and Britain continued to buy Norwegian goods, which helped prices rise further, and both the domestic economy and society came under increased pressure. The Norwegian government’s response was to print more money, which again led to strong inflation and compounded the effect on peoples’ rising cost of living. The government introduced cost of living allowances to reduce the impact of inflation for those hit the hardest. In addition, authorities introduced price controls on housing and sugar, and rationed certain other goods. The new regulations had only limited effect and encouraged a thriving black-market economy, which contributed to rising social tensions.

The war compounded these economic difficulties and the increased social hardship at home. During the autumn of 1916, German submarines sank a number of Norwegian merchant ships in the North Sea. In October 1916, the Norwegian government responded by adopting a resolution that was aimed at preventing German submarines from entering Norwegian territorial waters. German authorities considered the decision a provocation and it caused a great strain on Norwegian-German diplomacy. Germany’s declaration of unrestricted submarine warfare in February 1917 pushed Norway further in a westerly direction, as the country felt compelled to increase its trade with Britain.

In Norway, rising inflation and economic hardship fuelled discontent and unrest in both the labour movement and society in general. During the summer of 1917, the labour movement called for a nation-wide protest march (“dyrttids” demonstrasjon), which in Christiania (later Oslo), the capital, gathered more than 40,000 people with slogans demanding “peace and bread”.[9] In a manifesto, the labour movement called for a price reduction on consumable goods, a stop in the export of foodstuffs such as fish, a reduction of fuel prices, increased funding for local cost-of-living programs, and the expropriation of what they considered vital factories and businesses. A few months later, the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia further radicalised large parts of the labour movement and strengthened their demands for action from the government.[10]

Negotiations with the United States↑

The United States’ entry into the war on the side of the Allies in April 1917 put further pressure on Norwegian society and its policy of neutrality. As neutral countries, the United States and Norway had been politically aligned with shared interests. Norwegian companies traded peacefully with the United States, and the country had to a large extent replaced Britain as Norway’s prime trading partner, with American imports becoming increasingly important for the country’s economy. In June 1917, however, the U.S. government stopped or restricted all export to neutral countries, including Norway. U.S. authorities were concerned that neutral countries would re-export American goods to Germany and wanted to re-negotiate all existing trade deals with neutral countries.[11] The Norwegian government dispatched the explorer and scientist Fridtjof Nansen (1861-1930) as head of a delegation to Washington to negotiate in late summer 1917. The U.S. decision left Norway in a perilous situation, as the country had grown increasingly reliant on U.S.-imports of essential commodities such as coal, oil, and other raw materials. It was important for the Norwegian economy and society to conclude negotiations swiftly and decisively with the Americans. This was not to be. Instead, the negotiations became a protracted process that stretched into 1918. A major obstacle were American and Allied demands for limiting Norwegian trade and exports to Germany. Norwegian authorities accepted some limitations on its trade with Germany, but refused a large reduction and used its position as neutral state as a counter-argument stating that Norway did not want to favour one side over the other. In Norway, many blamed the government for the delay, and indeed historian Roald Berg has argued that Prime Minister Knudsen was hoping that Germany and the Allies were close to reaching a peace agreement in early 1918.[12]

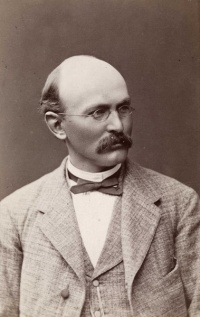

The wait-and-see-policy adopted by the government led to criticism in parliament, as the supply situation became ever more difficult. During the autumn and winter of 1917, unemployment rose and factories shuttered due to the shortage of imported goods. A radicalised labour movement and rising cost of living for the population compounded the situation and increased dissatisfaction with the government. In parliament, both the minister of foreign affairs, Nils C. Ihlen (1855-1925), and Oddmund Vik (1858-1930), the minister of provisioning, became the target of opposition criticism. Edvard Hagerup Bull (1855-1938), parliamentary leader for the Conservative Party, and Johan Castberg (1862-1926), of the Labour Democrats, demanded a no-confidence vote in the government. These efforts failed due to the Liberal Party retaining a majority, but it did not discourage further calls for a coalition government. Prime Minister Knudsen’s response to the harsh criticism of his government’s handling of the negotiations with the United States and increased economic difficulties was to ask for Oddmund Vik’s resignation in late November 1917.[13]

Meanwhile, restrictions on imports from the United States were taking a further toll on Norwegian society. In January 1918, the government introduced rationing of a number of commodities such as sugar, coffee, corn, and flour. Furthermore, the cost of living, including rent, fuel, and other expenses continued to rise as resources became limited. The country had not experienced such a dire supply situation since the British blockade during the Napoleonic wars. The protests of the labour movement intensified and in some places they formed soldier and worker’s councils. Furthermore, in March 1918 they held another large protest march (“dyrtids” demonstrasjon) across the country to protest the rising cost of living for the working class. The Liberal government attempted to meet this unrest with diplomacy and promises of more funding for those hardest hit by the rising costs. The government also used these protests and the radicalization of the Norwegian labour movement as a bargaining chip during the negotiations with the Allies, but with little success. In late April 1918, however, Nansen reached an agreement with U.S. representatives.[14] The resumption of trade came as a relief to the Norwegian economy and society, but the terms of the agreement pushed Norway further towards the Allies and restricted trade with Germany.

Conclusion↑

In late October 1918, Norway held another general election and Gunnar Knudsen’s government suffered a significant defeat, losing its majority in parliament. While the Conservative Party emerged as a winner, Knudsen would continue as prime minister due to his willingness to cooperate with the Labour Party, which had made some minor gains. The Liberal’s reversal at the ballot box was in large parts due to the strains of war and the hardship caused by the protracted negotiations with the U.S. In addition, the reverberations of the Russian Revolution had radicalised both the political left and antagonised the right, which had resulted in an increasingly polarised society. Everyone on the political spectrum considered neutrality an unqualified success, and it would prove to be the guiding light for successive Norwegian governments throughout the inter-war period and later world crises.

Eirik Brazier, University College of Southeast Norway

Reviewed by external referees on behalf of the General Editors

Notes

- ↑ Hobson, Rolf et al.: Introduction. Scandinavia in the First World War, in: Ahlund, Claes (ed.): Scandinavia in the First World War, Lund 2012, pp. 28-29.

- ↑ Fuglum, Per: Én skute - én skipper. Gunnar Knudsen som statsminister [One Ship, one Captain. Gunnar Knudsen as Prime Minister], Oslo 1989, pp. 218-222; Berg, Roald: Norge på egen hånd 1905-1920 [Norway on its Own 1905-1920], volume 2, Oslo 1995, pp. 189-191.

- ↑ Fuglum, Én skute 1989, pp. 203-205.

- ↑ Berg, Norge 1995, p. 191.

- ↑ Furre, Berge: Norsk Historie, 1905-1990, Oslo 1992, pp. 61-62.

- ↑ Fuglum, Én skute 1989, pp. 228-230.

- ↑ Vogt, Per: Jerntid og jobbetid. En skildring av Norge under verdenskrigen [Iron Times and Work Times. A Description of Norway during the World War], Oslo 1938.

- ↑ Berg, Norge 1995, p. 253

- ↑ Furre, Norsk Historie 1992, p. 71.

- ↑ Stugu, Ola Svein: Norsk historie etter 1905 (Norwegian history after 1905), Oslo 2011, pp. 54-55.

- ↑ Berg, Norge 1995, pp. 229-243.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 237.

- ↑ Fuglum, Én skute 1989, pp. 320-323.

- ↑ Berg, Norge 1995, pp. 241-243.

Selected Bibliography

- Ahlund, Claes (ed.): Scandinavia in the First World War. Studies in the war experience of the northern neutrals, Lund 2012: Nordic Academic Press.

- Alexa Døving, Cora / Thorson Plesner, Ingvill / Brandal, Nik. (eds.): Nasjonale minoriteter og urfolk i norsk politikk fra 1900 til 2016 (National minorities and indigenous people in Norwegian politics from 1900 to 2016), Oslo 2017: Cappelen Damm akademisk.

- Berg, Roald: Norge på egen hånd 1905-1920 (Norway on its own 1905-1920), Oslo 1995: Universitetsforlaget.

- Fuglum, Per: Én skute, én skipper. Gunnar Knudsen som statsminister (One ship, one captain. Gunnar Knudsen as prime minister), Trondheim 1989: Tapir.

- Furre, Berge: Norsk historie 1905-1990. Vårt hundreår, Oslo 1992: Norske samlaget.

- Keilhau, Wilhelm: Norge og verdenskrigen (Norway and the world war), Oslo 1927: Aschehoug.

- Stugu, Ola Svein: Norsk historie etter 1905. Vegen mot velstandslandet (Norwegian history after 1905. The road to a country of prosperity), Oslo 2012: Det norske samlaget.

- Vogt, Per: Jerntid og jobbetid. En skildring av Norge under verdenskrigen (Iron times and work times. A description of Norway during the world war), Oslo 1938: Johan Grundt Tanum.