Introduction↑

Delville Wood, a small forest adjacent to the Somme town of Longueval, was the site of the first substantial blooding of the 1st South African Infantry Brigade on the Western Front. For nearly a week in July 1916, South Africa’s men stood their ground there against German advances. They emerged days later much diminished in numbers, but not defeated. Delville Wood and the exploits of the men who fought there would become the focal point of memorialisation of South African valour on the Western Front during the Great War — white South African valour. This did not change until the twilight years of apartheid when greater recognition was given to the contribution of black and coloured South African citizens in their respective manifestations of wartime valour.

Views of the War↑

The commencement of the war precipitated a short-lived Afrikaner rebellion in South Africa from 14 September 1914 to 4 February 1915 against the pro-British Empire government under General Louis Botha (1862-1919).[1] This manifested the divided views on the country’s participation in this war, strongly influencing the kind of commemoration which was undertaken in its wake. Botha’s willingness to contribute troops to the war against Germany, which had rendered moral support and weapons exports to the Boer Republics in the late 1890s, seemed anathema to many South Africans from the aforementioned territories. A memorandum generated by the Union Defence Force (UDF) regarding the raising of a force for service in German South West Africa noted with concern the "spirit of antagonism and disloyalty displayed by a very large section of the population towards any suggestion of … assistance to the cause of the Allies". The Union government's crushing of the Afrikaner Rebellion did not quench the "smouldering ashes [that] still remained in the bosoms of a large section of the public in this country." The report deemed it vitally important not to strip the country of all of its loyal citizens at this critical time.[2]

At the end of the South African War of 1899-1902, tensions between British and English-speaking South Africans and Dutch/Afrikaans-speaking South Africans would pave the way for a “long history of conflict that had aggravated a strongly anti-British sentiment... leaving ‘the reverberations of menace’”.[3] Although the war’s end in 1902 set in motion a series of events which would, in 1910, constitutionally unify the four separate territories within present day South Africa, namely the Cape Colony, Natal, the Orange Free State and the Transvaal Republic, tensions between “Boer and Brit”, would not slacken; nor was the inexorable build-up of segregation laws against the non-white population of the country dulled. Chief among these laws was the 1913 Native Land Act. These policies would eventually be seen in the division of the UDF's Great War contribution along racial lines.[4]

The South African Native Labour Contingent (SANLC) was constituted by the Union government with great reluctance in the face of British War Cabinet calls to draw upon the Union's black citizens for non-combatant labour in French ports, railheads, quarries and forests to free up able-bodied whites for service at the fronts. The South African Cape Corps (SACC) drew on the South African coloured community, who would serve under arms in Africa and the Middle East in a way that their black counterparts could not. The white domination of commemoration until the advent of true democracy in South Africa in 1994 and lack of non-white commemoration is indicative of the title of South African academic and author Mohamed Adhikari’s book Not White Enough, Not Black Enough. Racial Identity in the South African Coloured Community.[5]

The Afrikaner Rebellion raised uncomfortable introspective questions for the Botha government in that the Union benefitted financially from association with Britain in the wake of the signing of the Treaty of Vereeniging in 1902. This grated on the sensibilities of those "bitter einders”—Boer generals and commandos who fought to the very end—who viewed the British scorched earth and concentration camp policies as injustices that went without retributive consequence. Assisting Britain undoubtedly weighed heavily on Botha and Jan Smuts (1870-1950), prompting them to prosecute the rebellion’s leaders on their own terms lest the empire despatch dominion forces to crack down on the uprising.[6]

Following the successful conclusion of the campaign in German South West Africa, the Union redeployed its forces elsewhere in Africa, Palestine, Mesopotamia, and most notably on the Western Front in France and Belgium. Its citizens acquitted themselves with conspicuous gallantry, bravery and valour, which became the subject of much commemoration after the conflict. Until the years preceding the country’s democratic transition in 1994, it was the exploits of the white South African contribution that were overwhelmingly memorialised.

Bill Nasson refers to Delville Wood as signifying a sacred place towards which these veterans gravitated to commune with their fallen comrades and pay their respects by erecting crosses and improvised markers from shattered timbers in that war-torn spot.[7] The hallowed ground of the South African Great War fallen is for some as remote as the manner in which the diverse constituent UDF forces are memorialised and commemorated, if at all—apart, based on race.

The Chronology and Colour of South African Great War Memorials↑

A speech by George V, King of Great Britain (1865-1936), delivered at Terlincthun British cemetery in the French Pas de Calais on 11 May 1922, contained phrases now familiar to many acquainted with the work of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC). The king’s lines, influenced by Rudyard Kipling (1865-1936), who accompanied the king on the monarch’s so-called pilgrimage to the Western Front in 1922, rang:

The famed writer and poet Kipling contributed prose in support of the British cause in the Boer War, and travelled to South Africa during that conflict, assisting the wounded and drafting newspapers for the troops. The words are oft quoted by the CWGC, underscoring the loss and sacrifice of war.

In 1924, Alexander Cambridge, 1st Earl of Athlone (1874-1957) paraphrased the king in a perhaps premeditated commemorative narrative at the unveiling of the Great War Cenotaph in Cape Town. This memorial stands out from other memorials at the time, with the inclusion of a panel depicting some of the exploits of the South African coloured community’s soldiers fighting in the SACC in Palestine. It did not highlight the effort of the black men of the SANLC who laboured instead of fighting. At the unveiling ceremony the Earl of Athlone said to those attending that:

The SANLC soldiers made the same journey as their white and coloured compatriots from around Cape Town, specifically from the Rosebank Camp where they were quartered to the docks to board departing troopships. Their lack of representation on the cenotaph is a physical manifestation of the racial discrimination and disregard shown at that time by the white minority towards its proportional counterparts in the Union.

After the war, efforts by South African industry and society notables such as author, politician, political advisor and mining financier Sir Percy FitzPatrick (1862-1931) of the classic children’s novel Jock of the Bushveld fame (based on his experience with his loyal dog “Jock” in the 1880s as a pioneer and transport rider on the Eastern Transvaal goldfields) gained momentum. The first of two South African war memorials was built at Delville Wood. FitzPatrick’s initiative to pay respect to the dead through the “two minute silence” was endorsed by the British Crown and contributed substantially to the establishment of the 11 November Armistice Day commemorations, which persist around the world.[10] FitzPatrick’s motivation was spurred on by the fact that his own son, Major Nugent Fitzpatrick (1889-1917), of the South African Heavy Artillery, was, like Rudyard Kipling’s son John Kipling (1897-1915), a Lieutenant of the 2nd Battalion Irish Guards, killed on the Western Front.[11]

The South African Memorial at Delville Wood is composed of a semi-circular flint stone screen, and was eventually unveiled on 10 October 1926. Later, on 11 November 1986, the Delville Wood Commemorative Museum, constructed as a miniature of the castle at the Cape of Good Hope in Cape Town, was unveiled.[12] This effort sought to honour not only the dead at Delville Wood but also put black and coloured faces who made the ultimate sacrifice for their country in the First World War alongside their white counterparts.[13] While commemorating all South Africans, the museum’s commemorative content and character left black and coloured representation in the minority. Many returning soldiers were painfully aware of those comrades that they had left behind, and banded together to represent the interests of returned servicemen and the dependents of the fallen.

Veterans’ Organisations↑

Millions of men and women returned at war’s end with uncertain futures. When the ardours of demobilisation manifested themselves to the point of great concern for authorities, three notable soldiers and leaders of the Great War, Field Marshall Douglas Haig, 1st Earl Haig (1861-1928), General Sir Jan Smuts and General Sir Henry Lukin (1860-1925) led the initiative to found the British Empire Service League (BESL). The inaugural meeting of the BESL was held in Cape Town’s city hall on 21 February 1921, coincidentally the anniversary of the sinking of the troopship SS Mendi on 21 February 1917, when hundreds of members of the SANLC drowned. The troopship Mendi was conveying SANLC members on their English Channel crossing from Plymouth to Le Havre, France when it was struck in the early morning fog by the cargo steamship SS Darro, resulting in the deaths of 616 South Africans of the SANLC, 608 of them black men. Since then, the South African chapter has evolved in keeping with the changing pro and anti-war sentiments of the post-World War I and pre-World War II era, first being dubbed the “British Empire Service League (South Africa)”, and then, in 1942, the “South African Legion of the BESL”. It was renamed the “South African Legion of the British Commonwealth Ex-Services League” in 1952.[14] The present day BESL, known as the Royal Commonwealth Ex-Services League, maintains links with Commonwealth veterans’ organisations around the world, and in South Africa most notably the South African Legion of Military Veterans.

Very shortly after the SACC contingent fighting in German East Africa was blooded in November 1917, the unit inaugurated a Cape Corps Memorial Fund and sought a site to memorialise its members’ sacrifice. At the time of demobilisation and even by 1926, with the publication of Ivor Difford’s rich and effusive account of the 1st Battalion Cape Corps’ exploits, the site and form of any proposed memorial was unresolved. While the mayor of Cape Town was approached for assistance with regards to a suitable location, the number of memorials being erected and lack of space curtailed any acceptable proffer from the authorities.[15] The SACC victory over the Ottoman Turkish lines with the capture of Square Hill between 18 and 21 September 1918 in Palestine, referred to by Difford as “… a great day—great for the Empire, great for South Africa and the coloured races thereof, and the greatest day in the history of the 1st Battalion Cape Corps,”[16] receives little or no concerted recognition today.

The most enduring and popular commemoration of the First World War, conceived of by a veteran, for veterans, is the world-renowned Comrades Ultramarathon held in South Africa’s Kwazulu-Natal. The race was brought to life by South African First World War veteran Vic Clapham (1886-1962), who wanted to commemorate the comrades he lost whilst with the 8th South African Infantry, which fought and marched some 1,700 miles in its skirmishes with the German General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck (1870-1964) and his askari in German East Africa.[17] The first race was run on 24 May 1921.[18] The marathon has an average of over 10,000 runners and is considered the most popular road race in South Africa and the biggest ultramarathon in the world.[19]

A Century of Commemoration Revisited↑

At the memorial service held at the Cape Town city hall on “Delville Day”–Sunday 17 July 1921—the cult of commemoration was strongly intertwined with language of religious and imperial duty. The dean of Cape Town called, amongst others, to: “Let us offer our thanksgiving to almighty God. For the devotion of our king, the honour of statesmen, and the unity of the empire in the face of a common danger” as well as “For the spirit of our soldiers, and the courage with which they endured, and especially for the men of the South African Brigade.”

The commemoration for the fallen was in this case not explicitly for one racial group or another, though in the immediate post-war years the enshrining of memorials to South Africans would be overwhelmingly aimed at the white community, with the contributions of the SANLC and SACC coming decidedly last. The Delville Wood Memorial with its bronze sculptures atop vaulting stone arches, consecrated in 1926, has smaller scale analogues in both the Company Gardens in Cape Town and the Union Buildings in Pretoria, with General Lukin commemorated through a statue in the Company Gardens in the Cape Town city centre.[20]

The addition of the Delville Wood Commemorative Museum to the Delville Wood memorial landscape in 1986 was not without controversy, as there was great opposition in South Africa from ex-servicemen’s organisations at the exorbitant projected cost of construction and furnishing. At the time of the laying of the foundation stone in 1984, the cost stood at some R6 million, equivalent to some 4.5 million US dollars at the contemporary exchange rate. Opposition felt the money could be better spent supporting veterans who had limited access to funds.[21]

The South African government and its Department of Defence and Department of Military Veterans has left a Mendi legacy by renaming a warrior-class strike craft of the South African Navy after Reverend Isaac Dyobha (1852-1917), the chaplain in the SANLC who drowned in the Mendi tragedy after having reportedly called his panicked brothers in arms to calm and exhorting the dancing of the now legendary “death dance” on the deck of the sinking ship. The words attributed to his address that fateful day are indicative of the conditional service rendered by black South Africans, when he was purported to have said to his doomed compatriots that:

While on its voyage home from the shipyard in Germany where it was constructed, the South African Navy Valour-class frigate SAS Mendi made a rendezvous, on 24 August 2004, with the Royal Navy destroyer HMS Nottingham for a wreath-laying ceremony at the wreck site.[22] The Order of Mendi for Bravery is awarded to South African citizens who have performed extraordinary acts of courage and bravery.[23] In 2012, the South African government’s executive declared 21 February as Armed Forces Day, in honour of the men lost in the troopship Mendi disaster.

On 23 February 1914, at the Mendi memorial celebration at Bantu Sports Grounds in Johannesburg, Dr. Alfred Bathini Xuma (1893-1962), president of the South African National Native Congress (SANNC, the forerunner of the African National Congress), plainly stated the desire for the black contribution to a great war past and another rapidly unfurling to be remembered in equality and fraternity, saying:

The two events of Delville Wood and the Mendi come symbolically together today, as at the Delville Wood Memorial Museum with the re-interring of the remains of the first SANLC member to die in France, on 22 November 1916. This was accomplished as an endeavour by the South African government to promote reconciliation and nation-building.[25]

The Arques-La-Batailles British Cemetery near Dieppe in northern France holds 380 casualties, with 377 identified war dead, of which 270 are listed as members of the SANLC who perished while performing logistics and manual labour in France during the war. The memorial in the centre of the cemetery is composed of a “Great War stone” with a concave bronze medallion which is adorned with the head of a springbok in high relief, bearing an inscription etched into the stone in English, Sesotho and isiXhosa reading:

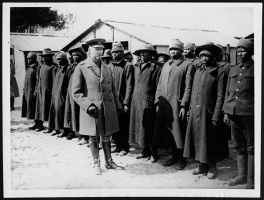

As a representative of the great chief, Edward VIII, Prince of Wales (1894-1972) visited Cape Town from 30 April to 2 May 1925, inspecting a parade of former SANLC troops[26], and was present at the inauguration of the carillon in Cape Town on 30 April.[27] Such a royal visit came full circle almost seventy years later, on 23 March 1995, when Elizabeth II, Queen of the United Kingdom, unveiled a memorial to the Mendi dead at Avalon Cemetery in Soweto, alongside President Nelson Mandela (1918-2013).[28] Considering the pre-1994 influence of legislated segregation and apartheid, these acts were small but not insignificant in providing a slight measure of recognition for the blood let in the First World War by non-white South Africans.

Transformative Commemoration↑

In comparing the loss of life and commemoration of dead from the Second World War with that of the one which preceded it, historian Jay Winter noted that in most cases the names of the fallen in the Second World War were affixed to the memorials to the fallen from the First World War, and pointed to the sentiment of Rudyard Kipling that "the names of the fallen are what matter most."[29] For Winter, the far-flung Commonwealth nations that answered the call to arms are, even today, largely unable to make pilgrimages to the memorials in the Somme, Flanders, Palestine and elsewhere, and for them, the names are all that remain.[30]

With the centenary of the Great War, the one hundred year commemorations of the Battle of the Somme and Delville Wood in July 2016, and the loss of the Mendi having come and gone, the South African government and its Defence Force have played a prominent role in marking the passing of its citizens on far-flung battlefields.[31]

Conclusion↑

South Africa’s then President Jacob Zuma used the opportunity at Armed Forces Day proceedings in Durban on 21 February 2017 to state that:

The centenary commemorations of the Battle of Delville Wood took place on 12 July 2016, with the unveiling of a transformed Delville Wood commemorative museum with permanent exhibitions which highlight not only the events at Delville Wood by the 1st South African Infantry Brigade but also the contributions, exploits and sacrifices of the SANLC and SACC. Zuma would also officiate over the unveiling of a new memorial wall of remembrance there which bears the alphabetically listed names of all South Africans who fell during the first and second world wars. The intention was that they be remembered in equality, irrespective of race, culture, language or military unit. The memorial walls are flanked by a garden of remembrance to those who have no known grave.

21 February 2017 saw black, white and coloured descendants of Mendi casualties and survivors go to the ship’s English Channel grave on board the South African Navy frigate SAS Amatola to pay their respects as part of South Africa’s centenary commemorations of that great disaster. It is poignant that the Amatola’s crew, just like the Mendi men’s descendants, are integrated and serve and coexist alongside each other one hundred years on. In academia, the University of Cape Town’s Centre for African Studies commemorated the sinking of the SS Mendi with its conference entitled “Ukutshona kukaMendi”/ “Ukuzika kukaMendi”.[33] The conference sought to explore the historical struggle against oppression and dispossession associated with the SANLC contribution to the First World War.[34]

In his first public address as president of the Republic of South Africa on the 21 February 2018 Armed Forces Day, in the Northern Cape capital of Kimberley, Cyril Ramaphosa highlighted the year’s theme—the centenary of the birth of Nelson Mandela—and said that “It is this SANDF that President Mandela envisaged as a non-partisan unifier and defender of all South Africans.” In Kimberley, where the Ottoman Turkish field gun captured by the SACC at Square Hill rests, Ramaphosa reminded all with a quote by the author S. E. K. Mqhayi (1875-1945) from his poem “Ukutshona kukaMendi” of the sacrifice made by all South African men and women in uniform who have paid the ultimate price for the country:

Be consoled, all you young widows!

Somebody has to die, so that something can be built

Somebody has to serve, so that others can live…The centenaries of the Battle of Square Hill and Armistice Day await in September and November 2018, and in the vein of commemoration and veneration, South Africa’s tributary voyage to its First World War dead continues on uncertain seas—a contested cult of commemoration.

Jacques Jean Pierre de Vries, University of South Africa

Section Editor: Timothy J. Stapleton

Notes

- ↑ Strachan, Hew: The First World War. To Arms, Volume 1, Oxford 2003, p. 546.

- ↑ DC Box 755, Memorandum to the Raising of the S.A. Overseas Expeditionary Force, n.d., p. 1.

- ↑ Nasson, Bill: The War for South Africa. The Anglo-Boer War 1988-1902, Cape Town 2010, p. 257.

- ↑ Grundlingh, Albert M.: War and Society. Participation and Remembrance. South African black and coloured troops in the First World War, Stellenbosch 2014, p. 3.

- ↑ Adhikari, Mohamed: Not White Enough, Not Black Enough. Racial Identity in the South African Coloured Community, Athens 2005.

- ↑ Warwick, Rodney: 1914. SA, WW1 and Afrikaner Rebellion, issued by South African History Online, online: http://www.sahistory.org.za/sites/default/files/1914_sa_ww1_and_afrikaner_rebellion.pdf (retrieved: 16 February 2016).

- ↑ Nasson, Bill: Delville Wood and South African Great War Commemoration, in: The English Historical Review 119/480 (2004), pp. 61-62.

- ↑ Commonwealth War Graves Commission Pamphlet, Their Name Liveth For Evermore.

- ↑ Cenotaph War Memorial Restored in Time for Remembrance Day, issued by the Cape Town Central City Improvement District, online: http://www.capetownccid.org/news/cape-town%E2%80%99s-cenotaph-war-memorial-restored-time-remembrance-day (retrieved: 26 July 2018).

- ↑ Dix-Peek, Ross: The other Percy Fitzpatrick. The Life and Death of Major Percy Nugent Fitzpatrick, South African heavy Artillery, (1889-1917), issued by The South African Military History Society, online: http://samilitaryhistory.org/ross/opercy.html (retrieved: 26 July 2018).

- ↑ Brown, Jonathan: The Great War and its Aftermath. The Son Who Haunted Kipling, issued by The Independent, online: http://www.independent.co.uk/arts-entertainment/books/features/the-great-war-and-its-aftermath-the-son-who-haunted-kipling-413795.html (retrieved: 17 February 2016).

- ↑ Paratus 37/12 (December 1986), pp. 20-25.

- ↑ de Vries, Jacques Jean Pierre: South Africa’s Western Front Great War Memory and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, issued by DefenceWeb, online: http://www.defenceweb.co.za/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=31175:south-africas-western-front-great-war-memory-and-the-commonwealth-war-graves-commission&catid=56:diplomacy-a-peace (retrieved: 17 February 2016).

- ↑ About the South African Legion, issued by South African Legion of Military Veterans, online: http://www.salegion.co.za/about-the-sa-legion.html (retrieved: 18 February 2016).

- ↑ Difford, Ivor Denis: The Story of the 1st Battalion Cape Corps (1915-1919), Cape Town 1926, p. 332.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 219

- ↑ History, issued by Comrades Marathon Association, online: http://www.comrades.com/home-about/history-of-comrades (retrieved: 26 July 2018).

- ↑ How it All Began, issued by Unogwaja, online: http://unogwaja.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/comrades-history.pdf (retrieved: 18 February 2016).

- ↑ Tuesday, 24 May 1921. The First Comrades Marathon Takes Place, issued by South African History Online, online: http://www.sahistory.org.za/dated-event/first-comrades-marathon-takes-place (retrieved: 18 February 2016).

- ↑ Final Report of South African National Memorial (Delville Wood) Committee, July 1931.

- ↑ Veterans Condemn Museum, in: Cape Times, 12 July 1984.

- ↑ Memorial Wreath Laying for the SS Mendi and Her Crew, issued by South African Navy, online: http://www.navy.mil.za/newnavy/surface/mendi040823/i040823_update.htm (retrieved: 20 February 2016).

- ↑ The Order of Mendi for Bravery, issued by The Presidency, online: http://www.thepresidency.gov.za/national-orders/order-mendi-bravery-0 (retrieved: 26 July 2018).

- ↑ An Address at the Mendi Memorial Celebration, Bantu Sports Grounds, Johannesburg, issued by South African History Online, online: http://www.sahistory.org.za/archive/address-mendi-memorial-celebration-bantu-sports-grounds-johannesburg-dr-b-xuma-february-23-1 (retrieved: 20 December 2016).

- ↑ South African National Defence Force: The Reserve Force Volunteer (Summer 2015), p. 37.

- ↑ Clothier, Norman: Black Valour. The South African Native Labour Contingent, 1916-1918, and the Sinking of the Mendi, Pietermaritzburg 1987.

- ↑ Lewis, C. A. / De Wet, T. / Teugels, J. L. / Van Deventer, P. J. U.: Bells as Memorials in South Africa to the Great (1914-18) War, in: The Ringing World 5378 (2014), p. 550.

- ↑ South Africa. Queen Elizabeth II Visit, issued by Associated Press, online: http://www.aparchive.com/metadata/South-Africa-Queen-Elizabeth-II-Visit/d035b899498eea40db4cbc70698322b7?query=south+africa+mandela¤t=3&orderBy=Relevance&hits=3&referrer=search&search=%2Fsearch%3Fquery%3Dsouth%2520africa%2520mandela%26allFilters%3DPOOL%3ASource%2CSoweto%3ALocations&allFilters=POOL%3ASource%2CSoweto%3ALocations&productType=IncludedProducts&page=1&b=8322b7 (retrieved: 30 April 2016).

- ↑ Winter, Jay: Remembering War. The Great War Between Memory and History in the 20th Century, New Haven 2006, p. 157.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Andersen, Roy: An Overview of Selected South African Memorials, in: South African National Defence Force: Reserve Force Volunteer (Summer 2016), pp. 20-25, issued by Defence Reserves Republic of South Africa, online: http://www.rfdiv.mil.za/documents/magazines/Summer%202016.pdf (retrieved: 14 November 2016).

- ↑ SA. Jacob Zuma. Address by President of South Africa and Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces, on the occasion of Armed Forces Day, Durban (21/02/2017), issued by Polity, online: http://www.polity.org.za/article/sa-jacob-zuma-address-by-president-of-south-africa-and-commander-in-chief-of-the-armed-forces-on-the-occasion-of-armed-forces-day-durban-21022017-2017-02-21 (retrieved: 22 March 2017).

- ↑ University of Cape Town. “Ukutshona kukaMendi”/ “Ukuzika kukaMendi”. The Mendi Centenary Conference, issued by Centre for African Studies, online: http://www.africanstudies.uct.ac.za/cas/features/2016/mendi/conference (retrieved: 27 July 2018).

- ↑ Mendi Centenary Conference Programme, 28-30th March, 2017, issued by Centre for African Studies, online: http://www.africanstudies.uct.ac.za/sites/default/files/image_tool/images/327/Events/Mendi%20Centenary%20Conference%20%E2%80%93%20FINAL%20Programme.pdf (retrieved: 01 May 2017).

Selected Bibliography

- Adhikari, Mohamed: Not white enough, not black enough. Racial identity in the South African coloured community, Athens; Cape Town 2006: Ohio University Press; Double Storey.

- Buchan, John: The history of the South African forces in France, London; New York 1920: T. Nelson and Sons.

- Clothier, Norman: Black valour. The South African Native Labour Contingent, 1916-1918, and the sinking of the Mendi, Pietermaritzburg 1987: University of Natal Press.

- Difford, Ivor Denis: The story of the 1st Battalion Cape Corps (1915-1919), Cape Town 1920: Hortors.

- Grundlingh, Albert M.: Fighting their own war. South African Blacks and the First World War, Johannesburg 1987: Ravan Press.

- Grundlingh, Albert M.: War and society. Participation and remembrance. South African Black and Coloured troops in the First World War, 1914-1918, Stellenbosch 2014: SUN Media.

- Nasson, Bill: World War One and the people of South Africa, Cape Town 2014: Tafelberg.

- Nasson, Bill: Springboks on the Somme. South Africa in the Great War, 1914-1918, Johannesburg; New York 2007: Penguin.

- Winter, Jay: Remembering war. The Great War between memory and history in the twentieth century, New Haven 2006: Yale University Press.