Introduction↑

Australia was part of the British Empire in 1914, so the British government's declaration of war on Germany meant Australia was automatically involved. However, because Australia was a self-governing dominion, it was the Australian government that determined the composition and extent of its military contribution. On the outbreak of war, the government transferred operational control of the Royal Australian Navy to the British Admiralty and created two volunteer expeditionary forces. The small Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force captured German New Guinea. The large Australian Imperial Force (AIF), in which 330,000 soldiers served overseas, fought against the Ottoman army in the Middle East from 1915 and the German army on the Western Front from 1916.

1914: Deploying the AIF↑

Australia was in the middle of a national election campaign when the First World War began. The Liberal Party government, led by Prime Minister Joseph Cook (1860-1947) with Senator Edward Millen (1860-1923) as defence minister, had a strained relationship with the military. Millen had embarked on a clumsy and controversial economy drive in his department. Sir Ronald Munro Ferguson (1860-1934), the Australian governor-general, privately told Lewis Harcourt (1863-1922), the British colonial secretary, that Millen lacked "the confidence of the Services".[1]

The federal election on 5 September 1914 returned the Labor Party to power with Andrew Fisher (1862-1928) as prime minister and Senator George Pearce (1870-1952) as defence minister. Due to ill-health, Fisher resigned in October 1915 and was succeeded by William Hughes (1862-1952). Hughes and Pearce retained their positions as prime minister and defence minister until the end of the war, but both left the Labor Party over the issue of conscription at the end of 1916, and, with other Laborites, form a coalition with the Liberal Party.[2]

Labor had been the main advocate of increased defence spending in response to Japan’s defeat of Russia in 1905 and emergence as a major power. Pearce had established an effective working relationship with Major-General William Bridges (1861-1915), whom Millen had appointed as general officer commanding (GOC) AIF and commander of the 1st Australian Division during his earlier terms as defence minister in 1908-1909 and 1910-1913.[3]

The convoy carrying the first contingent of the AIF was ready to depart on 21 September, and Bridges wanted the ships to sail immediately. Pearce took the issue to cabinet and overruled Bridges because there were German warships roaming the Indian and Pacific Oceans. Departure was delayed until 1 November, when Allied warships arrived to help escort the troopships carrying both the AIF and the New Zealand Expeditionary Force (NZEF).[4]

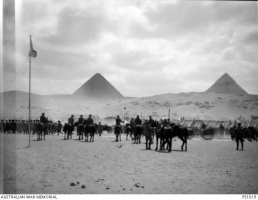

The convoy’s original destination was the United Kingdom, but Field Marshal Horatio Herbert Kitchener (1850-1916), the British war secretary, asked Sir George Reid (1845-1918), the Australian high commissioner in London (equivalent to an ambassador), to gain the Australian government’s approval for the AIF to disembark in Egypt. Kitchener told Reid that Egypt had better weather than England, where the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) were enduring sodden autumn weather in tents. The Australian government agreed, and the AIF and the NZEF began disembarking in Egypt on 3 December. The British government forgot to consult the New Zealand government, and it is clear that the real reason for landing the Australian and New Zealand soldiers in Egypt was not the English weather, but the need to protect British interests from external Ottoman attacks and internal Egyptian revolts.[5]

1915: Gallipoli↑

The AIF and the NZEF units were brought together in the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (Anzac) under the command of an Indian Army officer, General Sir William Birdwood (1865-1951). The Australians landed at Gallipoli on 25 April 1915, alongside British, French, Indian and New Zealand troops. When Bridges died of wounds on 18 May, Pearce immediately chose Major-General James Gordon Legge (1863-1947), the Australian chief of the general staff, to replace Bridges as both GOC AIF and 1st Australian Division commander.

This decision led to a significant civilian-military dispute. The three Australian brigade commanders at Gallipoli, James McCay (1864-1930), John Monash (1865-1931) and Henry Chauvel (1865-1945) all believed they should have been appointed to replace Bridges rather than Legge – who was known for having a difficult personality. General Sir Ian Hamilton (1853-1947), the British officer in command of the Mediterranean Expeditionary Force, asked Kitchener to overrule the decision. Munro Ferguson, a former officer in the Grenadier Guards, agreed, writing that Labor politicians like Pearce, who were "inured to Trade Unions and the Political Caucus, do not seem to appreciate generally the value of bon camaraderie in the Field". The governor-general told Pearce he should not have appointed Legge without consulting Hamilton and General Sir William Birdwood, commander of the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (Anzac). Legge retained his command despite this opposition. As Jeffrey Grey argues: "the British authorities were quite unwilling to try to contest or overturn it because they recognised fully that it was the Australian Government’s prerogative to make any such appointment as they saw fit".[6]

Both Bridges and Legge concentrated on their role as the 1st Australian Division commander, neglecting the more important position of GOC AIF, which included the administration and training of a large range of units from artillery batteries to field hospitals. This enabled the ambitious Birdwood to lobby Munro Ferguson and Pearce to become GOC AIF. Birdwood succeeded in convincing Pearce: in September 1915, Birdwood was given command of the AIF, a role he retained until the end of the war. Pearce insisted that Birdwood consult him on all AIF appointments above the rank of colonel to ensure that Australian rather than British officers should be chosen where possible.[7]

1917: Creating the Imperial Mounted Division↑

Following the failure of the Gallipoli campaign, the AIF infantry divisions moved to the Western Front in 1916, while the mounted troops of the Australian Light Horse remained in the Middle East to fight the Ottomans. In January 1917, General Sir Archibald Murray (1860-1945), the British commander in Egypt, proposed combining two veteran Australian Light Horse regiments with two recently-arrived inexperienced British yeomanry regiments to create a new formation to be called the Imperial Mounted Division. Murray asked the senior Australian officer in Egypt, Major-General Chauvel, to gain the Australian government’s approval for the new division. For reasons that remain unclear, Chauvel did not inform Pearce.[8]

It was not until the Imperial Mounted Division had fought in the First Battle of Gaza in March 1917 that the Australian government learned of its existence. Pearce complained and the War Office apologised for not informing him. The Australian government wanted an Australian Mounted Division to be formed instead, and was even willing for it to be commanded by a British officer. When another British yeomanry regiment arrived in Egypt in June 1917, Murray created a Yeomanry Mounted Division, and the Imperial Mounted Division became the Australian Mounted Division.[9]

1917: Australians and the Death Penalty↑

Unlike other British and Dominion troops, AIF soldiers were not executed during the Great War. Australians could be sentenced to death, and 121 men were during the war. However, the Australian Defence Act stated that a death sentence had to be endorsed by the governor-general before an execution could take place. The Australian government always directed the governor-general not to make this endorsement. Birdwood was not aware of the government’s policy when he became GOC AIF, and admitted to Munro Ferguson that he "might have had men shot illegally, causing endless trouble".[10]

Following the French army mutinies in April 1917, senior British officers on the Western Front became concerned by the desertion rates of Australian soldiers, which were far higher than those in the rest of the British and dominion forces on the Western Front. Birdwood and General Sir Alexander Godley (1867-1957), who commanded the corps containing the five Australian infantry divisions, wrote to Pearce requesting that Australian troops be made liable for execution. The British government made the same request to Hughes in August. Hughes did not bring the issue to cabinet because he believed former Liberal ministers would leak the story to the newspapers. Instead, Hughes had private discussions with two or three trusted ministers and decided that the political costs of executing Australian soldiers and its effect on voluntary recruiting outweighed any military benefits. Walter Long (1854-1924), the British colonial secretary, eventually realised the necessity of the Australian decision.[11]

1917-18: "Anzac Leave"↑

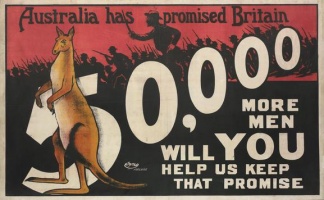

The Australian people had voted against introducing conscription for overseas service in October 1916. Voluntary enlistments continued to decline during the first part of 1917, so Hughes and Pearce called for men to join up to enable soldiers who had enlisted in the AIF in 1914 to be able to return to Australia on "Anzac leave". In September 1917, the Australian government made a formal request to its British counterpart to introduce "Anzac leave". The British government rejected the proposal, stating that if one dominion gained leave for its expeditionary force veterans, all the other dominions would also demand it. In fact, the Canadian and New Zealand governments had made the same request to the War Office, and – perhaps because New Zealand had introduced conscription and Canada was in the process of doing so – 1,000 CEF and a smaller number of NZEF soldiers had been granted home leave before it was halted by the German offensive in March 1918.

Birdwood must have known of the Canadian and New Zealand programs. Sympathetic to his soldiers’ plight, he created a covert "Anzac Leave" policy in February 1918 by assigning "1914 men" to carry out "submarine guard duty" on transports returning invalided soldiers to Australia. Birdwood dared not mention this in his regular telegrams to Pearce, telling him in a private letter that if the plan became public "neither your life nor mine would be worth living". When Hughes arrived in the United Kingdom in June 1918, he insisted on an official "Anzac leave" program for 7,500 "1914 men" that commenced in September.[12]

1918: Command of the Australian Corps and AIF↑

During 1917, Hughes, Pearce and Birdwood had called for the five Australian infantry divisions to be combined – like the Canadian divisions – into one corps. General Sir Douglas Haig (1861-1928) approved the creation of the Australian Corps in November 1917. Birdwood took command of the Australian Corps, and retained the position of GOC AIF. In May 1918, Haig appointed Birdwood to command the British Fifth Army. Birdwood told Pearce he wished to continue as GOC AIF until the war ended and the soldiers had been returned to Australia. Birdwood recommended Major-General Sir John Monash to take command of the Australian Corps.[13]

Birdwood’s proposal was threatened when Hughes, who was in the United States on his way to London, was lobbied by two influential Australian journalists, Charles Bean (1879-1968) and Keith Murdoch (1885-1952), to appoint Major-General Sir Brudenell White (1876-1940), Birdwood's chief of staff, to command the Australian Corps and make Monash GOC AIF. Bean believed White to be the better general and his opinion of Monash was tainted with anti-Jewish prejudice. However, when Hughes arrived in London on 15 June, he realized – contrary to what Murdoch and Bean had told him – that Monash had great support among both Australian and British commanders. Hughes finally approved Monash’s command of the Australian Corps on 19 June 1918.[14]

Hughes decided to replace Birdwood as GOC AIF with either Monash or White because he believed Birdwood would not stand up for Australian interests if this brought him into conflict with his British superiors. On 12 August, Hughes offered Birdwood the choice of retaining command of either the Fifth Army or the AIF, expecting the general to give up the AIF to keep his army command. Birdwood consulted Haig, who quite reasonably did not want to change commanders in the middle of a major offensive, and came up with an alternative option. This was that Birdwood would continue as GOC AIF, but would be loaned to command the Fifth Army until 30 November. Pearce, who was willing for Birdwood to continue with the AIF, was amused when he read the correspondence and saw how Birdwood and Haig had outmanoeuvred Hughes. He commented to Munro Ferguson: "No wonder our Generals beat the Germans".[15]

Conclusion↑

The Australian government was generally successful in asserting civilian control over Australian and British generals during the Great War. The government ensured the promotion of Australian officers on merit, and held firm to policies such as opposing the death penalty. The British government – with few exceptions, such as the refusal to allow "Anzac leave" – recognised Australia’s authority as a self-governing dominion to make decisions regarding its soldiers. As Jeffrey Grey has concluded: "The notion that the Australian Government was subservient to British interests… during the war is little more than a caricature."[16]

John Connor, University of New South Wales

Section Editor: Peter Stanley

Notes

- ↑ Connor, John/Stanley, Peter/Yule, Peter: The War at Home, Melbourne 2015, p. 84.

- ↑ Connor, John: Anzac and Empire. George Foster Pearce and the Foundations of Australian Defence, Melbourne 2011, pp. 76-77.

- ↑ Connor, Anzac and Empire 2011, p. 13, pp. 19-20 and pp. 62-64.

- ↑ Connor, Anzac and Empire 2011, pp. 47-48.

- ↑ Grey, Jeffrey: The War with the Ottoman Empire, Melbourne 2015, p. 26.

- ↑ Connor, Anzac and Empire 2011, pp. 64-65; Grey, War with the Ottoman Empire 2015, pp. 65-68.

- ↑ Connor, Anzac and Empire 2011, p. 65; Grey, War with the Ottoman Empire 2015, p. 26.

- ↑ Connor, Anzac and Empire 2011, pp. 103-104.

- ↑ Connor, Anzac and Empire 2011, p. 104; Grey, War with the Ottoman Empire 2015, pp. 109-110; 125-126.

- ↑ Connor, Anzac and Empire 2011, pp. 106.

- ↑ Stevenson, Robert: The War with Germany, Melbourne 2015, pp. 112-113; Connor, Anzac and Empire 2011, pp. 106-107.

- ↑ Connor/Stanley/Yule, War at Home 2015, p. 134.

- ↑ Connor, Anzac and Empire 2011, p. 120.

- ↑ Serle, Geoffrey: John Monash: A Biography, Melbourne 1982, pp. 320-328.

- ↑ Connor, Anzac and Empire 2011, pp. 121-122.

- ↑ Grey, War with the Ottoman Empire 2015, p. 65.

Selected Bibliography

- Andrews, E. M.: The Anzac illusion. Anglo-Australian relations during World War I, Cambridge; New York 1993: Cambridge University Press.

- Beaumont, Joan: Broken nation. Australians in the Great War, Crow's Nest 2013: Allen & Unwin.

- Bridge, Carl: William Hughes. Australia, London 2011: Haus Publishers.

- Connor, John: Anzac and empire. George Foster Pearce and the foundations of Australian defence, Cambridge; New York 2011: Cambridge University Press.

- Connor, John / Yule, Peter / Stanley, Peter: The centenary history of Australia and the Great War. The war at home, volume 4, Melbourne 2015: Oxford University Press.

- Cunneen, Christopher: Kings' men. Australia's governors-general from Hopetown to Isaacs, Sydney; Boston 1983: G. Allen & Unwin.

- Day, David: Andrew Fisher. Prime minister of Australia, Pymble 2008: HarperCollins.

- Fitzhardinge, L. F.: The little digger 1914-1953. William Morris Hughes. A political biography, volume 2, London 1979: Angus & Robertson.

- Grey, Jeffrey: The war with the Ottoman Empire, Melbourne 2015: Oxford University Press.

- Pedersen, Peter Andreas: Monash as military commander, Melbourne 1982: Melbourne University Press.

- Serle, Geoffrey: John Monash. A biography, Carlton; Beaverton 1982: Melbourne University Press.

- Stevenson, Robert C.: The war with Germany, Melbourne 2015: Oxford University Press.