Introduction↑

The impact of the First World War on Canada reshaped Canada politically, socially, and economically.[1] In terms of human costs, of a population of eight million Canadians, over 650,000 enlisted and 425,000 served overseas; some 66,000 were killed. The centenary presented an opportunity to recount a seminal period in Canadian history. This paper explores Canada’s response to the Great War centenary of 2014-2018 and serves as an evaluation of commemorative efforts. It includes an inventory of trends and approaches taken to remember Canada’s experience in the Great War, highlighting various examples of commemorative acts from across the nation and overseas. It also considers Canada’s response in terms of remembering well, as defined below.

Over the past 100 years, Canada’s cultural war memory, and subsequently the nation’s approach to commemoration, has evolved. The post-war era was very much focused on validating the immense sacrifice, driven in large part by veterans and next of kin and as a means to counter perceptions of senseless loss.[2] Two contrasting perspectives characterize Canada’s approach to the centenary:

- expectations for a high-profile national effort and for a local approach to commemoration that competes for limited funding with other heritage priorities;

- celebrating the birth of a nation through First World War narrative and coming to terms with how the tragedy of war continues to haunt families, communities, and the nation.

These contrasts informed, to an extent, national and community approaches to the centenary.

During the centenary, Canadians participated in a range of acts of remembrance, including pilgrimages to battlefields, exhibits, plays, books, educational endeavours, films, and community events. Generating a comprehensive inventory of commemoration in Canada is challenging for many reasons, the most significant being a lack of national or central coordinating agency. Nevertheless, in addition to academic literature, this paper is able to draw from a range of news, social media, websites, and government documents. Hyperlinks build out the depth and breadth of discussion, providing access to examples of educational resources, video footage of some of the films and national commemorations that took place, as well as data for future research.

Before moving forward with an exploration of centenary commemoration, some brief perspective on the concept of remembrance. The term is employed here as the action of remembering; an acknowledgement of the war and those who died in it.[3] For Winter, individuals act of their own accord to remember, in their own way, even if it is done within the setting of a "state-invented" collective commemoration such as Remembrance Day (November 11), observed in Canada and elsewhere in the world.

The concept of remembrance, however, is complex and still lacks clarity. Epistemologically, war remembrance differs by generation, culture, and one’s relationship or connection to a given war and to the dead. LeShan describes remembrance as mythic for the post-war generations, shaped by a blend of family stories, schooling, books, film, and museums, along with engagement in rituals and traditions of commemorative events and by visiting sites of war memory such as memorials, cemeteries, and battlefields.[4] Ever-present in commemoration is the concern of masking the horror of war, of sentimentalizing or justifying and accepting violence and slaughter.[5] The complexity of remembrance is also reflected in the challenge faced by government agencies in measuring the benefit of funded acts of remembrance such as films, conferences, and events, or even the value of guided tours of battlefields.[6] A fundamental question then is: how does one remember well in the 21st century?

Remembering well involves consideration of both the quantitative and qualitative elements of acts of remembrance. Quantity, in terms of the number of commemorative events and the level of participation, is important to build access, momentum, and maintain profile. This element is typically and more easily used to measure the value or success of an event. But, remembering well also involves considering acts of remembrance from a qualitative perspective, in terms of their relevance, level of engagement, and meaning for individuals. It can also involve deepening and broadening the range of useable pasts beyond what Smith describes as the authorized heritage discourse.[7]

It is the qualitative element of remembering well that remains somewhat elusive in that it is difficult to define and measure. Even 100 years on, remembrance for an individual can involve emotion, imagination, and personal memories that trigger a sense of connectedness with the past. Commemoration still matters because it remains a means to honour as well as release the trauma of war and death. How we interpret the past also informs the present. In this way, the qualitative element of remembering includes personal memory work and what we teach and learn to inform contribution to contemporary society.

More research is required to conceptualize "remembering well" as a means to harness a greater good from collective remembrance. This would involve drawing on a broad spectrum of disciplines and subjects, from addressing intergenerational and ancestral grief, to ways in which commemorative events and sites of war memory, as educational resources, are managed, interpreted, and experienced. This paper considers remembering well in general terms, considering the quantitative outcomes from the perspective of funding, number of events, and participation as well as the qualitative aspect of remembering well, charting the level of engagement and relevance.

First, we start with a look at the contemporary context of Canada in 2014-18 and its influence on the centenary. Second, the discussion turns to agents and acts of remembrance. We outline the role of key agencies and their policies and approach to the centenary. Examples of commemorative acts provide a sense of scope, depth, and character of Canada’s 2014-2018 experience. The next section focuses on survey findings and evaluations by both government and other commemorative agencies. Finally, we offer a synthesis and some perspectives on remembering well.

Commemoration in Contemporary Context: Canada in 2014-2018↑

This section offers a snapshot of some of the social and political context, by way of editorials, and the critical events that shaped the tone and profile of the centenary. By understanding context, we begin to piece together what "remembering well" means in Canada and for Canadians.

With a population of over 36 million in 2018, Canada has become increasingly diverse, shifting away from the predominantly white British immigrants of the early 20th century. While it could be argued that the percentage of foreign-born in Canada was higher in the Great War era, some 20 percent of today’s population is foreign-born, mostly from non-European countries and many without a familial connection to the Great War. By 2031, 32 percent of the population is projected to belong to a visible minority.[8] Only 29 percent of Canadians indicate that they have a family connection to the First World War.[9] However, in 2016, 25 percent indicated that they attended a commemorative event in the previous year, the highest response amongst six "Western Front" nations.[10]

Leading into 2014, the conservative government, in power from 2006 to 2015, was aware of criticism of its handling of the 200th anniversary of the War of 1812. Over 28 million Canadian dollars were spent on commemorations of a war with little meaning for most Canadians.[11] The government interpreted the criticism as a lesson learned for 2014-2018: no additional funding would be allocated for the centenary. When the liberals came to power in September 2015, they continued what can be described as downplaying the centenary.

Even before the centenary’s official start date, a national editorial asked, "Why is Canada Botching the Great War Centenary?", lambasting the government’s approach from both a quantitative and qualitative perspective.[12] Central to J. L. Granatstein’s concerns was that no new money had been allocated, and, the national commemoration planned for the Battle of Vimy Ridge in 2017, there were few signature events or initiatives planned to mark the four years. His call for new funding offered a rationale:

The First World War centenary straddled an equally significant national moment for Canada: its sesquicentennial, also known as Canada 150, marking the creation of the Dominion of Canada. The two anniversaries offered a uniquely concentrated opportunity for reflection on the Great War and its role in shaping Canadian identity. Approximately $200 million was allocated to Canada 150 "signature initiatives".

The government’s priority was to celebrate and commemorate the entirety of the Canadian historical experience, with defined thematic areas: diversity and inclusion, national reconciliation with Indigenous peoples, engaging and inspiring youth, and the environment. The Great War could be woven into some of Canada 150’s priorities; it was a matter of the extent to which acts of remembrance would be supported amongst other heritage and culture projects. The final accounting as to what actually happened with Canada 150 funding will only gain clarity with the next government audit.

Nevertheless, the Canadian First World War narrative is often framed as part of nation-building, with the Battle of Vimy Ridge in 1917 ascending in legend as the place where "Canada was born". With Canada 150 also occurring in 2017, there was a unique symmetry to the Vimy narrative. Many argued that the Vimy anniversary should serve as a seminal event in the Canada 150 calendar, and essentially that is what happened, as discussed later in this paper.

Informing both Canada 150 and the Great War centenary was another critical event: the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (2015).[13] For all the potential for national pride during the centenary, a parallel, more disturbing narrative was that of Canada’s treatment of Indigenous people, described in the report as "cultural genocide". Bringing this story to light does not wash away the sacrifices made by Canadians in the Great War. In the context of the centenary, there was more attention paid to Indigenous veterans and their contribution in the war, and the poor way they were treated upon return.[14] It also illustrates another dimension in the politics of remembrance in Canada. One example is a growing awareness of Canada’s ignoble legacy as colonizer which contributes to the self-critical nature of Canadian national identity in the 21st century.

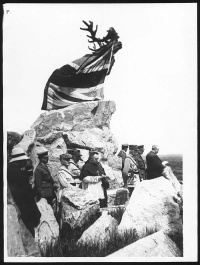

Whereas every region of Canada was significantly affected by the war, Newfoundland and Labrador, a dominion until it joined confederation in 1949, warrants specific mention. While over 3,000 Newfoundlanders joined the Canadian Expeditionary Force, it is the experiences of the 1st Newfoundland Regiment (earning the prefix "Royal" later in the war) in the British Army that deeply resonate in the province’s cultural memory. The regiment was decimated on the first day of the Battle of the Somme at Beaumont Hamel, 1 July 1916. In the provincial capital of St. John’s, the annual modern-day July 1 morning commemoration[15] of this battle is juxtaposed with Canada Day celebrations in the afternoon. Whether there is a direct line between the war’s impact and Newfoundland joining Canada is one of debate. What is clear is that after the war, Newfoundland was awarded five national memorials to Canada’s eight, an illustration of the significant profile of the Great War in the memory of Newfoundlanders. Today, all of the memorials, known collectively as the Trail of the Caribou, are under the stewardship of the Canadian government, warranting what would be an intriguing investigation as to how the war experience of Newfoundland was subsumed into the nation it joined 30 years later.[16]

With regard to the quantitative element of remembering well, the centenary was immediately challenged in terms of the legacy of the 1812 commemoration and competing for funds within the framework of Canada 150. Given its own unique history, Newfoundland’s commemorations involved both federal and provincial funding and therefore present a more successful approach to remembering well than in other jurisdictions.

An Overview of Agents and Acts of Remembrance in Canada, 2014-18↑

Various agents of remembrance – government organizations, museums, community, and regimental groups – engaged Canadians during the centenary. This section gives a flavour of their initiatives along with analysis of the Canadian approach to commemorating the centenary.

Governments are often perceived as central funding and coordinating agencies with regard to war remembrance. For the government of Canada, remembrance is defined as "honouring and commemorating the sacrifices, achievements and legacy of those who served in Government of Canada sanctioned wars, conflicts, peacekeeping and aid missions, in both military and civilian capacities".[17] Primary responsibility for implementing policy rests with Veterans Affairs Canada, with agencies such as Heritage Canada, Parks Canada, and National Defense each with their own funding to allocate. For the centenary, a federal government stakeholders committee was formed to coordinate national projects.

Prior to 2014, Canadian Heritage identified a modest number of key 100-year anniversaries it would highlight: the start of the war; the Second Battle of Ypres and the writing of In Flanders Fields by Canadian John McCrae (1872-1918) (2015); Somme and Beaumont Hamel (2016); Vimy (2017); the last 100 days; and the armistice (2018). However, absent from the 2016-2017 and 2017-2018 Canadian Heritage annual planning documents is any mention of the centenary, eclipsed at that time by Canada 150. Nevertheless, a number of grant programs did see a significant spike in community proposals tied to the centenary.[18] This contrast represents the disconnect between government policy and the public profile of the centenary.

Heritage and culture also fall under provincial jurisdiction. Whereas provincial heritage and arts grants to communities, museums and cultural groups would have no doubt included requests to support centenary activities, there was no specific grant for the First World War centenary in any of the provinces and territories. In contrast, several provinces and territories did create a Canada 150 fund. There were, however, some initial efforts to explore levels of interest in the centenary. For example, in British Columbia, a coalition of interested agencies held a provincial planning forum. The final report outlined the need for provincial coordination, and suggestions on approaches, but there was little follow up to the event.[19] For remembering well to occur, not only is funding required, but some form of planning and coordination. The overall result was that commemorative efforts were meaningful yet isolated, local endeavours, with little to no profile or dissemination achieved beyond local communities and organizations.

Notwithstanding, the Canadian National War Museum did play a prominent role. It expanded permanent exhibits related to the First World War and set forward with a number of temporary[20] and travelling[21] exhibits. Community, provincial, and national museums and libraries were commemorative focal points across the country. Examples of local efforts include the community library[22] in Saanich on Vancouver Island, the revamped virtual museum[23] of the Fusiliers Mont-Royal, and the Alberta Museum’s[24] focus on memory and the First World War. For Newfoundland, a major exhibit entitled Beaumont-Hamel and the Trail of the Caribou[25] captured the profound impact of the war on Newfoundland and Labrador. These initiatives exemplify efforts to focus on the local relevance of war heritage.

One particularly significant and innovative national initiative was taken on by Library and Archives Canada (LAC). Launching the largest digitization project in its history, the LAC scanned personnel files of Canadians who served in the First World War. Completed in 2018, the First World War Database[26] offers over 30 million digitized images in over 622,000 personnel files. This project formally sets the use of digital device applications as a resource for remembering well: one can now locate a war grave using the CWGC app[27] and then, in situ, remotely access the individual’s personnel file by way of the LAC. Augmenting this work is the Newfoundland Provincial Museums and Archives, known as The Rooms, which also created a comprehensive digitized resource[28], as well as personnel files[29]. As a learning resource, this technology transforms the visitor’s engagement with a war grave in Canada or overseas, enabling a deeper level of knowledge, analysis, and reflection.

A number of documentaries were produced for the centenary. For Newfoundland, two nationally-aired documentaries, Trail of the Caribou[30] (CBC 2016) and Newfoundland at Armageddon (CBC 2016) exemplify the significance of the war for Newfoundland and how that memory has been subsumed by Canada as a whole. Other documentaries include World War One Hidden Stories. Canada's Soldier[31] (2014), 14-18: La grande guerre des Canadiens[32] (2014), and the Great War Tour(2018)[33]. And yet, there remains a dearth of film, either documentary or "docu-drama", that has achieved critical or popular acclaim.

Scores of books were also published on the topic of the Great War, from national to regional narratives.[34] Notable were two books that fuelled a debate regarding the significance of the Battle of Vimy Ridge in Canadian cultural memory. Ian McKay and Jamie Swift wrote The Vimy Trap. Or, How We Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Great War and Tim Cook produced Vimy. The Battle and Legend.[35] Whereas Cook provides a more historical account, McKay and Swift’s work, as outlined in a CBC radio show[36], is more polemic and much less research-based. Nevertheless, these books represent the ongoing discourse on fusing national identity to the legacy of the war.

Universities and academics of various disciplines also played a role in the centenary. Centres of study at universities such as at Wilfred Laurier[37], Calgary[38], and New Brunswick[39] all served as inspiration for various conferences and research initiatives. Vancouver Island University has a project for digitized and published soldiers’ letters and photos[40]. Royal Roads University has a rich set of educational films on war heritage sites[41]. Other agencies such as the Vimy Foundation[42], Valour Canada[43], and the Royal Canadian Legion[44] all offer educational programming and resources intended to generate greater awareness, particularly at the secondary school level. However, the overall impact of these efforts is not adequately understood.

Within the Canadian commemorative approach was a concerted effort to acknowledge minorities, their contribution or reconciling how they were treated. Rather than tokenism, this effort was a means of reconciliation, a form of commemorative diplomacy within the multicultural setting that is Canada. Many of these were reliant on government funding, mostly at the federal level. They are also examples of broadening and deepening our understanding of the war, which can be considered a trait of remembering well. Some examples include:

- Ukrainian and German Internment: the Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund established a series of memorial markers and interpretive signage[45]

- Chinese Labour Corps: in 2014, a memorial was unveiled at the William Head Quarantine station[46] where they made landfall[47]

- Métis Nation Veterans Monument[48] at Batoche: completed in 2016

- Indo-Canadian war heritage: a series of resources[49] were developed

- The Black Battalion: an exhibit[50] and a short film[51] in Halifax, Nova Scotia[52]

- Refurbishing the Japanese Canadian War Memorial, Stanley Park: Ied by the Nikkei National Museum & Cultural Centre (CBC 2014)[53]

- Exhibit on Mennonite pacifism during the First World War (CBC 2017)[54][55]

Community-level commemorations occurred across the country and offer a range of qualitative examples of remembering well. In Victoria, British Columbia, a boulevard of trees was rededicated as Memorial Avenue[56]. In Nova Scotia, the community of Joggins added ten names to its memorial[57]. One concerted effort to commemorate the armistice took place in Cobourg, Ontario, billed as Canada’s largest commemoration.[58] These particular instances indicate the geographic reach as well as the depth of interest to take on a range of significant commemorative initiatives.

Some individuals took on their own acts of commemoration with varying levels of success. Most notably, in 2013, a businessman proposed to construct a memorial of "Mother Canada" in a national park.[59] Controversial from the start, the project mobilized age-old debates about due process, suitability, design, role, location, cost, and the overall value of memorials in fostering and sustaining war memory. This example underlines how efforts at commemoration, although well meaning, face a range of funding, bureaucratic, and philosophical obstacles and further support the need for a better understanding of remembering well.

The collective character of this disparate range of acts of remembrance reflects the local commitment of groups and individuals to remember, a kind of 21st century crowd-sourcing to commemorate the Great War. Despite what these acts offered in effort and local benefit, collectively they were unable to achieve any kind of sustained nation-wide impact or legacy. Aside from the complaints of limited financial resources and no national coordination, the geographic separation between home front and the battlefields of the Western Front is another obstacle in commemoration. This is particularly true given the powerful sense of place associated with national memorials such as Beaumont Hamel and Vimy.

The Vimy Commemoration and Other Events Overseas↑

Acts of remembrance also took place at sites of memory overseas where Canada has national memorials at historic battlefields. The anniversary of the Battle of Vimy Ridge was inevitably the high watermark of Canada’s commemoration in the Great War centenary.[60] In addition to marking the April 1917 battle, the Vimy memorial, preserved battlefield, trenches, and tunnels stand alongside a new interpretation centre (completed in 2017) as the Canadian national memorial for the First World War. The legend of Vimy holds a unique status in Canada’s cultural memory.[61] When Canadian General Sir Arthur Currie (1875-1933) was involved in selecting the site after the war, he feared placing the national memorial at this location would overwhelm the memory of other, more significant battles, and in some ways his concern has transpired, despite efforts to memorialize other battlefields such as Hill 70[62]. But with its new interpretation centre and Canadian guides, Vimy also serves as a gateway to visit and learn about other sites of war memory in the area.

The 2017 event involved some 25,000 Canadian visitors. It was also a highly orchestrated televised [63]affair. It was the only commemorative event overseas where the prime minister of Canada spoke, joined by representatives of the British royal family and the president of France.

Among the crowd were 10,000 red-jacketed youth from Canada. They represented a turning point in the significance of tourism as an act and agent of remembrance. A company called Education First Tours organized the largest pilgrimage of Canadian youth, with little fanfare and no government support. Private sector involvement to this extent marks the evolving commodification of remembrance. What was notable here was the Vimy Education Expo[64] the following day, which was innovative in the way it engaged youth to synthesize commemorative messages in a contemporary context. This project represented a formal effort to enable students to remember well, by way of a range of learning activities that linked what was commemorated to contemporary issues and challenges.

Aside from the epic nature of Vimy as a national legend, other events had a more local feel, representing an invention of tradition spurred by the centenary. Another example of remembering well was the anniversary of the Battle at Kitcheners’ Wood on 22 April 2015. One hundred years after the midnight attack on the same field, a storage barn was converted to host over 300 Canadian and Belgian guests in what was a uniquely inspiring evening[65] involving food, drink, music, and a shared war legend. A century on, the event evolved a bond between communities, and with this, cultural understanding and friendship.

Another example of a "homegrown" act of remembrance took place on the armistice anniversary in the town of Mons, Belgium. In addition to the formal Canadian delegation of politicians and the military, a pipe band, involving individuals from six provinces and three countries, arrived to march through the town, re-enacting a similar event of a hundred years ago.[66] These two events exemplify the fictive kinship to specific stories and battles that many Canadians have learned and adopted as their own and demonstrates the power of remembrance as a connector of people and cultures.

Remembering well can benefit from travel to sites of war memory as it enables an embodied, and often a transformative, experience. If Canada as a nation was indeed born during the Great War, it is the offspring of events in foreign lands. This circumstance situates some of Canada’s most significant heritage sites overseas, accessible only to those who can afford the journey. This bifurcation between the nation and its sites of war memory, although not unique to Canada, represents a significant obscuring trait in remembrance.

Measuring Canada’s Great War Centenary: Engagement, Momentum, and Relevance↑

A range of surveys assessed public awareness and engagement during the centenary. While some findings generate more questions than answers, they also expose, and in some cases confirm, key characteristics and challenges associated with remembrance in Canada in the 21st century. Findings point to the ongoing need to support commemoration so that it retains its relevance, the challenge of regionalism, and for open discourse. Other results allude to policies and practices that fall short in terms of continuing public engagement, as well as the need for a deeper understanding of how remembrance works. A few key results are presented here.

At the midpoint of the centenary, a 2016 survey conducted by the Vimy Foundation found that 52 percent of Canadians felt that enough was being done to mark the 100th anniversary, leaving almost half wanting either more or less. A government audit confirms the regional bias toward commemorations. Awareness of the anniversaries of the two world wars varied from a high of 71 percent in Ontario, to a low of 57 percent in Quebec.[67] This difference in part reflects the divisiveness of the conscription issue between English and French Canada. Awareness from year to year was also a challenge. As an example, in 2017, 75 percent of those polled said the Battle of Vimy Ridge was important, perhaps attributable to the national televised event. One year later, research found a decrease in the ability to recognize the iconic memorial.

Interestingly, government initiatives received relatively high marks. Almost 90 percent of Canadians surveyed felt that the annual Veterans Week, involving public outreach, was important to maintain.[68] The evaluation of Canadian Heritage programs found 80 percent of Canadians agree that commemorations are effective at increasing historical awareness and build a sense of pride and belonging to Canada.[69] Taking into consideration the challenges of awareness, one may interpret that the government programs were well received and deemed worthy, but they were not sufficient in scale and scope to generate and maintain awareness over the four years.

However, there were some notable criticisms. For instance, one recommendation was to "remove all non-essential barriers to applications for commemoration funding such as requirements for: a positive story, or participation in existing institutions, or national pride."[70] This message aligns with calls for reconciliation, inclusion, and acknowledgement of contested histories relevant to the diversity of Canada today. This kind of change may be a positive step toward remembering well in the future.

There is also a growing awareness of what is not understood about remembrance, one example being the value of visiting battlefields overseas. One particular recommendation was to "develop and implement measures to capture visitor experience feedback associated with Veterans Affairs Canada’s memorial sites in Europe".[71] While there has been significant investment in memorial parks, measuring the value of visiting a battlefield, at least in the eyes of the Audit and Evaluation Division, remains elusive.

Commemorative fatigue, particularly after the Vimy commemoration, was not quantified in surveys and audits to date. Nevertheless, there was a decline in public attention to battles such as Passchendaele and the Hundred Days Offensive, perhaps more because of the lack of a signature event and profile.

Conclusion↑

This paper provided examples that illustrate that many Canadians still care deeply about remembering the First World War. Surveys indicate a positive level of awareness, but also suggest that Canadians have an ongoing need for commemorative events at home and overseas. Travelling to battlefields stands as a resonant and often transformative act of remembrance for Canadians. But notably, in calls for more government funding and signature events, the challenge of "remembering well" plays out: Canada’s efforts were simply not of the same quantity or breadth as in other jurisdictions around the world. Aside from the signature event of Vimy 100, Canada’s efforts primarily rested with local efforts to commemorate. Whereas the qualitative aspect of commemorations has not been formally measured, we can see that relevance, engagement, and resonance were greater in overseas events in comparison to those held in Canada.

The call for a high-profile national effort was argued in Granatstein’s 2014 editorial, foreseeing too few events and not enough of a nation-wide profile. Four years later, an article concluded that "Historians [were] unimpressed with Canada's First World War centenary commemorations", the primary measure being expenditure.[72] The article argues that whereas Canada’s Veterans Affairs spent $13 million, Australia spent some $80 million and New Zealand about $20 million. In Australia’s case, real spending levels may have been four times Lee Berthiaume’s estimate. Nevertheless, Berthiaume forcefully makes the case that Canada's centenary effort pales in comparison.

Two editorials published on the 2018 armistice weekend reflect a difference in how the First World War is remembered. In The Long Shadow of the Great War, Tim Cook asserts, "… a century later, the First World War continues to haunt us". He argues that the centenary of the First World War is an important signpost, that dates matter. They increase media attention and capture the attention of Canadians.[73] Further on, he clarifies, "It matters because we, as Canadians, have said it matters. Not all Canadians care, of course, but enough do." His summary captures the essence of Canada’s four years of commemoration.

Adjacent to Cook’s three-page discourse, retired General Rick Hillier offers the classic perspective with his editorial entitled, “Canada Was Forged in Trenches of the First World War”.[74] The article takes a strategic view of Canada’s involvement in the war, echoing what Hillier once coined the "Vimy Effect"[75]: that the leadership, training, and innovation required for Canada’s war effort was "what it takes to build a nation and what it takes to maintain one". Side by side, Cook and Hillier present the two perspectives that reflect in part the terrain walked by Canada, Canadians, and the four years of commemoration: one of haunting remembrance, the other a celebration of nation-building.

The judgment that Canada failed with the Great War centenary may seem harsh. For many Canadians, Canada’s war experience continues to remain meaningful, important and an integral part of modern citizenship. Some 25,000 Canadians including over 10,000 youth travelled to Vimy in what was the nation’s largest commemorative pilgrimage since 1936. Indeed, acts of commemoration flowed on their own momentum, driven by communities of familial and fictive kinships, not as a coordinated government effort. The national government may have failed in their efforts, but many Canadians did not.

It is clear, however, that there is a primary role and responsibility for the government to ensure that the nation as a whole remembers well in perpetuity. Exploring how to best measure the return on commemorative investment will inevitably lead to reconsidering the meaning and role of remembrance. In a contemporary world challenged with hate, distrust, and greed, remembering well can be a means to instill greater compassion and a desire to contribute to positive change. Perhaps we can even be so bold as to have acts of remembrance aspire to practicing gratitude, and reflect deeply about the meaning of courage, vulnerability, joy, and empathy that are also part of the human condition. These qualitative elements are a tall order indeed and are not free from political manipulation. These are matters for future research and reflection.

As seen with the Canada 150 celebration themes including inspiring youth, reconciliation, and the environment, the future relevance of war commemoration may also involve reframing war histories to drive toward certain contemporary learnings or universal concepts. This may be the basis for remembering well: both as a civic responsibility and as a call to contribute to society in ways that may question the legitimacy and implications of warfare then and now. Such approaches lead not only to a sense of belonging within the nation at a time of immensely shifting demography and culture, but remind individuals of the importance of community, human rights, and our inextricable connection, as a nation, to the fate of humankind.

Geoffrey Bird, Royal Roads University

Section Editor: Bruce Scates

Notes

- ↑ Cook, Tim: Vimy. The Battle and the Legend, Toronto 2017.

- ↑ Vance, Jonathan: Death so Noble. Memory, Meaning, and the First World War, Vancouver 1997.

- ↑ Winter, Jay: Remembering War. The Great War between Memory and History in the Twentieth Century, New Haven 2006.

- ↑ LeShan, Lawrence: The Psychology of War. Comprehending its Mystique and its Madness, New York 1992. Reeves, Keir / Bird, Geoffrey / James, Laura / Stichelbaut, Birger / Bourgeois, Jean: Battlefield Events. Landscape, Commemoration and Heritage, Abingdon 2016.

- ↑ Mosse, G. L.: Fallen Soldiers. Reshaping the Memory of the World War, Oxford 1990.

- ↑ Government of Canada: Evaluation of Public Recognition and Awareness, p. 32, issued by Veterans Affairs Canada, online: https://www.veterans.gc.ca/pdf/deptReports/2017-evaluation-public-recognition-awareness/2017-evaluation-public-recognition-awareness-02.pdf (retrieved: 29 July 2019).

- ↑ Smith, L.: Uses of Heritage, London 2006.

- ↑ Statistics Canada: Immigration and Ethnocultural Diversity in Canada, issued by Statistics Canada, online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/nhs-enm/2011/as-sa/99-010-x/99-010-x2011001-eng.cfm (retrieved: 15 November 2018).

- ↑ Vimy Foundation: Survey of Six “Western Front” Nations Shows Canadians Most Likely to Have Attended War Remembrance Ceremony in Past Year, issued by Vimy Foundation, online: https://www.vimyfoundation.ca/survey-of-six-western-front-nations-shows-canadians-most-likely-to-have-attended-war-remembrance-ceremony-in-past-year/ (retrieved: 29 July 2019).

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Frenette, Yves: Conscripting Canada’s Past. The Harper Government and the Politics of Memory, in: Canadian Journal of History 49/1 (2014), pp. 49-65.

- ↑ Granatstein, J. L.: Why is Canada Botching the Great War Centenary? issued by the Globe and Mail, online: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/why-is-canada-botching-the-great-war-centenary/article18056398/ (retrieved: 25 October 2018).

- ↑ Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future. Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, issued by the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation, online: http://nctr.ca/assets/reports/Final%20Reports/Executive_Summary_English_Web.pdf (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ McInnes, B. D.: Sounding Thunder. The Stories of Francis Pegahmagabow, Winnipeg 2016.

- ↑ CBC NL - Newfoundland and Labrador: Beaumont Hamel 100 Remembrance. Full Program, issued by YouTube, online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xgjtil21WY8&list=FLw5Ip_k7Pfl7iYc57iaUipw&t=6417s&index=2 (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ Lemelin, Raynald Harvey: The Caribou Trail. Commemorating the Royal Newfoundland Regiment in the First World War, in: Frances, Raelene / Scates, Bruce (eds.): Beyond Gallipoli. New Perspectives on Anzac, Melbourne 2016. See also Beyond Gallipoli. New Perspectives on ANZAC, issued by Monash University Publishing, online: http://www.publishing.monash.edu/books/bg-9781925495102.html (retrieved: 29 July 2019).

- ↑ Government of Canada: Overarching Commemoration Evaluation March 2018. Audit and Evaluation Division, p. 1, issued by Veterans Affairs Canada, online: http://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/about-us/reports/departmental-audit-evaluation/2018-evaluation-overarching-commemoration (retrieved: 14 September 2018).

- ↑ Government of Canada: Evaluation of the Celebration and Commemoration Program 2011-12 – 2015-16, issued by Government of Canada, online: https://www.canada.ca/en/canadian-heritage/corporate/publications/evaluations/celebration-commemoration-program.html (retrieved: 29 July 2019).

- ↑ Projects, issued by the War Heritage Research Initiative, online: http://warheritage.royalroads.ca/projects/ (retrieved: 29 July 2019).

- ↑ Vimy – Beyond the Battle, issued by Canadian War Museum, online: https://www.warmuseum.ca/event/vimy-beyond-the-battle/ (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ Witness. Fields of Battle through Canadian Eyes, issued by Canadian War Museum, online: https://www.warmuseum.ca/witness/ (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ Saanich Archives: Saanich Remembers WWI, issued by District of Saanich, online: https://www.saanich.ca/EN/main/parks-recreation-culture/archives/saanich-remembers-wwi.html (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ Musée Regimentaire Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal, issued by l’Association des Fusiliers Mont-Royal, online: http://lesfusiliersmont-royal.com/musee/fr/ (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ Remembering the First World War, issued by Royal Alberta Museum, online: https://royalalbertamuseum.ca/visit/galleries/changing-exhibitions/remembering-first-world-war/ (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ Beaumont-Hamel and the Trail of the Caribou, issued by The Rooms, online: https://www.therooms.ca/exhibits/now/beaumont-hamel-and-the-trail-of-the-caribou (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ Library and Archives Canada, Personnel Records of the First World War, issued by Government of Canada, online: https://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/discover/military-heritage/first-world-war/personnel-records/Pages/personnel-records.aspx (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ War Graves App, issued by Commonwealth War Graves Commission, online: https://www.cwgc.org/learn/our-apps/war-graves-app (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ Entering the Great War, issued by The Rooms, online: https://www.therooms.ca/thegreatwar/the-beginning/entering-the-great-war (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ Military Service Files Database, issued by The Rooms, online: https://www.therooms.ca/thegreatwar/in-depth/military-service-files/database (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ Trail of the Caribou, issued by CBC News, online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/newfoundland-labrador/trail-of-the-caribou-1.3661371 (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ CBC News: The National: World War One Hidden Stories. Canada's Soldier (Full Network Special), issued by YouTube, online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=McsEN1_HfQM&index=2&list=FLw5Ip_k7Pfl7iYc57iaUipw&t=64s (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ 14-18: La Grande Guerre des Canadiens, issued by CBC/Radio-Canada.ca, online: https://ici.radio-canada.ca/premiere/balados/2702/14-18-la-grande-guerre-des-canadiens (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ The Great War Tour, issued by TVOntario, online: https://www.tvo.org/programs/the-great-war-tour (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ Winter, Michael: Into the Blizzard. Walking the Fields of the Newfoundland Dead, Toronto 2014. Norton, Wayne Reid: Fernie at War, Halfmoon Bay 2017. Humphries, Mark Osborne: A Weary Road. Shell Shock in the Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1914-1918, Toronto 2018.

- ↑ McKay, Ian / Swift, Jamie: The Vimy Trap. Or, How We Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Great War, Toronto 2017. Cook, Tim: Vimy. The Battle and the Legend, Toronto 2017.

- ↑ Information Morning Cape Breton: The Vimy Trap, issued by CBC News, online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/programs/informationmorningcapebreton/the-vimy-trap-1.3856894 (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ Laurier Centre for Military, Strategic and Disarmament Studies, issued by Wilfried Laurier University, online: http://canadianmilitaryhistory.ca/ (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ Centre for Military, Security and Strategic Studies, issued by University of Calgary, online: https://cmss.ucalgary.ca/ (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ The New Brunswick Military Heritage Project, issued by the Military and Strategic Studies Program of the University of New Brunswick, online: https://www2.unb.ca/nbmhp/index.htm (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ The Canadian Letters & Images Project, issued by Vancouver Island University, online: https://www.canadianletters.ca/ (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ War Heritage Research Initiative, issued by Royal Roads University, online: http://warheritage.royalroads.ca/ (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ The Vimy Foundation, issued by the Vimy Foundation, online: https://www.vimyfoundation.ca/ (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ Valour Canada. Connecting Canadians to their Military Heritage, issued by Valour Canada, online: http://valourcanada.ca/ (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ Royal Canadian Legion, issued by Royal Canadian Legion, online: https://www.legion.ca/home (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund, issued by the Canadian First World War Internment Recognition Fund and The Ukrainian Canadian Foundation of Taras Shevchenko, online: http://www.internmentcanada.ca/ (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ War Memories: Part 8. Chinese Labour Corps, issued by YouTube, online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=1&v=AZAf793THVQ (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ Johnson, Peter: Quarantined. Life and Death at William Station, 1972-1959, Victoria 2013.

- ↑ War Veterans, issued by Gabriel Dumont Institute of Native Studies and Applied research, online: https://gdins.org/metis-culture/veterans-monument/ (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ Duty, Honor and Izzat. The Call to Flanders Fields, issued by Indus Media Foundation Canada, online: http://imfc.org/ (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ New Temporary Exhibit at Pier 21 Commemorates the No. 2 Construction Battalion, issued by Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21, online: https://pier21.ca/new-temporary-exhibit-at-pier-21-commemorates-the-no-2-construction-battalion (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ = Legion Magazine: Military Moments. Canada’s First Black Battalion, issued by YouTube, online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YfaF9Y3KhwA&list=FLw5Ip_k7Pfl7iYc57iaUipw (retrieved: 9 July 2019)

- ↑ Luck, Shaina: How a Tiny French Town is Commemorating Canadian Black Battalion Soldiers, issued by CBC, online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/french-town-black-battalion-memorial-1.4798913 (retrieved: 24 October 2018).

- ↑ Drews, Kevin: First World War Japanese-Canadians Honoured with Refurbished Stanley Park Monument, issued by CBC News, online: https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/first-world-war-japanese-canadians-honoured-with-refurbished-stanley-park-monument-1.2732214 (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ CBC News: Battle of Vimy Ridge 100th Anniversary Commemoration, issued by YouTube, online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FSerGABNyL4&index=2&list=FLw5Ip_k7Pfl7iYc57iaUipw&t=7026s (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ Ali, Faisal: Exhibit Provides the Mennonite Take on the War to End all Wars, issued by Observer, online: https://observerxtra.com/2017/09/28/exhibit-provides-mennonite-take-war-end-wars/ (retrieved: 19 November 2018).

- ↑ Shelbourne Memorial Trees, issued by Gordon Head Residents’ Association, online: http://www.gordonhead.ca/gordonhead/Shelbourne_Memorial_Trees.html (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ Cole, Darrell: Joggins to Add 10 Names to its Cenotaph, issued by Amherst News, online: https://www.cumberlandnewsnow.com/news/local/joggins-to-add-10-names-to-its-cenotaph-228884/ (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ Armistice18, issued by Experience Cobourg, online: https://experiencecobourg.ca/history/armistice-18/ (retrieved: 9 July 2019).

- ↑ Campion-Smith, Bruce: New Memorial Envisioned to Honour Canada's War Dead, issued by The Star, online: https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2013/12/30/new_memorial_envisioned_to_honour_canadas_war_dead.html (retrieved: 5 November 2018).

- ↑ Vimy Ridge Centenary. Thousands of Canadians Mark Battle’s Anniversary, issued by BBC News, online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-39546875 (retrieved: 15 November 2018).

- ↑ Cook, Vimy 2017.

- ↑ Hill 70. Forgotten Victory, issued by Hill 70 Memorial Project, online: http://www.hill70.ca/ (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ CBC News: Battle of Vimy Ridge 100th Anniversary Commemoration, issued by YouTube, online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FSerGABNyL4&index=2&list=FLw5Ip_k7Pfl7iYc57iaUipw&t=7026s (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ EF Educational Tours Canada: Vimy 100 Highlights. EF Educational Tours Canada, issued by YouTube, online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pBPp7OkciD0&index=2&t=17s&list=FLw5Ip_k7Pfl7iYc57iaUipw (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ Vernon, Michael: Calgary Highlanders in Europe 2015, issued by YouTube, online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=li4krCiOmH4&t=2273s&list=FLw5Ip_k7Pfl7iYc57iaUipw&index=2 (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ Return to Mons 2018, issued by the Royal Highlanders Association, online: https://mons2018.blackwatchcanada.com/ (retrieved: 5 July 2019).

- ↑ Ibid., p. 14.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 16.

- ↑ Government of Canada, Overarching Commemoration Evaluation 2018, p. 13.

- ↑ Ibid., p. v.

- ↑ Ibid., p. ii.

- ↑ Berthiaume, Lee: Historians Unimpressed With Canada’s First World War Centenary Commemorations, issued by CTV News, online: https://www.ctvnews.ca/politics/historians-unimpressed-with-canada-s-first-world-war-centenary-commemorations-1.4174008 (retrieved: 12 Nov 2018).

- ↑ Cook, Tim: The Long Shadow of War, issued by the Globe and Mail, online: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/article-the-long-shadow-of-war-100-years-later-the-first-world-war-continues/ (retrieved: 10 November 2018).

- ↑ Hillier, Rick: Canada was Forged in Trenches of the First World War, issued by the Globe and Mail, online: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/article-canada-was-forged-in-trenches-of-the-first-world-war/ (retrieved: 29 July 2019).

- ↑ Hillier, Rick: Leadership. 50 points of Wisdom for Today’s Leaders, Toronto 2010.

Selected Bibliography

- Betts, Amanda: In Flanders Fields. 100 years. Writing on war, loss and rememberance, New York 2015: Knopf.

- Cook, Tim: Vimy. The battle and the legend, Toronto 2017: Allen Lane Canada.

- Cook, Tim: The secret history of soldiers. How Canadians survived the Great War, Toronto 2018: Allen Lane.

- Eamon, Michael: The war against public forgetfulness. Commemorating 1812 in Canada, in: London Journal of Canadian Studies 29/1, 2014, pp. 85-117.

- Johnson, Peter Wilton: Quarantined. Life and death at William Head station, 1872-1959, Victoria 2013: Heritage House Publishing.

- McKay, Ian / Swift, Jamie: The Vimy trap or, how we learned to stop worrying and love the Great War, Toronto 2016: Between the Lines.

- Reeves, Keir / Bird, Geoffrey / James, Laura et al. (eds.): Battlefield events. Landscape, commemoration and heritage, London et al. 2016: Routledge.

- Sjolander, Claire Turenne: Through the looking glass. Canadian identity and the War of 1812, in: International Journal 69/2, 2014, pp. 152-167.