Edith Louisa Cavell (1865-1915) was an English matron whose life changed course with the German invasion of Belgium in August 1914. The occupying German forces executed her on 12 October 1915 for helping stranded Allied soldiers and Belgian would-be soldiers enter neutral Holland. She then became one of the most famous women of the First World War. In May 1919, Cavell’s body was exhumed from the Tir National, where she had been shot and quickly buried, and transported to London for a memorial service in Westminster Abbey. She was then re-buried on the grounds of Norwich Cathedral, close to her birthplace, Swardeston.

Life in Brussels↑

In August 1914, Cavell was in Brussels working as a matron at the Berkendael Institute on Rue de la Culture, a thriving private training hospital. With an aptitude for French, Cavell had first gone to Brussels as a governess in 1890 and worked there for five years. In 1895 she returned to England to nurse her sick father and made up her mind to train as a nurse. In 1907, after an assortment of nursing positions, Cavell returned to Brussels through her previous connections, working as matron for Dr. Antoine Depage (1862-1925) after he opened a nursing school at his clinic. At the outbreak of war, the hospital was successfully introducing professional nursing techniques to Belgium and a new hospital was being built in the suburb of Uccle.

A Risky Endeavour↑

Cavell was immediately involved in the war. Her training hospital quickly came under the Red Cross flag and received wounded soldiers from battles on Belgian territory. After the Battle of Mons, Belgians began assisting men stranded on the wrong side of the trenches find shelter in homes and hospitals and then guiding them through Belgium and across the border into neutral Holland. Men who did not immediately surrender risked being shot by the Germans as spies. Herman Capiau (1884-1957), an intermediate of Antoine Depage’s wife, Marie Depage (1872-1915), allegedly arrived from the Mons region with the first two soldiers.

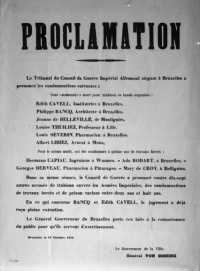

Cavell documented her escape work in notebooks and corresponded with her mother in England, who let her know when men arrived safely. There was a sense of impending doom about her assistance, as it was hard to keep the presence of so many men secret. In the months leading up to her arrest, the German police gathered evidence. When Cavell was taken into custody on 5 August 1915, she made a confession. Although she mentioned a figure of 200 men, it is likely that she helped as many as 1,000 men. At the court martial, held on 7 and 8 October 1915 at the Court of Brussels Senate House, Cavell appeared with thirty-five others, out of a total seventy people who were implicated in the escape network. Cavell was number five of nine people for whom the death penalty was sought. Architect Philippe Baucq (1880-1915), executed at the same time as Cavell, organised the distribution of the underground literature La Libre Belgique and Le Mot du Soldat. The network also helped potential Belgian and French recruits, and while Cavell was not herself a spy, the circle that she moved in was connected to passing information to the Allies.

On British request, Cavell’s arrest was investigated by the American Embassy in Brussels. While there were claims that the Germans behaved irregularly, Cavell’s confession made defence difficult, and martyrdom imminent.

From Nurse to Heroine↑

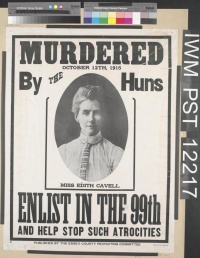

Cavell’s legendary status began after she was executed by firing squad at dawn on 12 October 1915. There were sensationalised accounts of her death that stressed German brutality. A "thrill of horror" and "wave of outrage" were felt around the Allied world. Cavell’s death backfired. It was intended to maintain order in Brussels, but instead played directly into the hands of the Allied propaganda machine, becoming particularly useful for recruitment. Roland Ryder estimated that Cavell’s death resulted in 40,000 extra recruits. Cavell was depicted as an innocent nurse, presented as much younger than her forty-nine years, who had died at the hands of barbaric Germans who posed a threat to British womanhood. Unrepentant, the Germans emphasised women and men’s equality before the law and that she had violated the conditions of Red Cross neutrality. However, Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941) ordered that no more women be executed without his approval.

Edith Cavell had strong high Anglican Christian convictions. In her final days spent in St. Gilles Prison she read and annotated a copy of Thomas à Kempis’ The Imitation of Christ. Her last words spoken to Reverend H. Stirling Gahan (1870-1959) on the night before her execution expressed her faith and transcendence of the horrors of war: "I know now that patriotism is not enough. It is not enough to love one’s own people: one must love all men and hate no one." These words were carried through the 20th century, appearing on Cavell’s London monument and on a Melbourne monument.

Edith Cavell was praised as a fine British woman and commemorated in diverse ways around the world, including with a mountain, a bridge, schools, hospitals and stone monuments.

Katie Pickles, University of Canterbury

Section Editor: Emmanuel Debruyne

Selected Bibliography

- Debruyne, Emmanuel: Le réseau Edith Cavell. Des femmes et des hommes en résistance, Brussels 2016: Racine.

- Pickles, Katie: Transnational outrage. The death and commemoration of Edith Cavell (2 ed.), Houndmills; New York 2015: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ryder, Rowland: Edith Cavell, New York 1975: Stein & Day.