Early Life and Career↑

Luigi Cadorna (1850-1928) was born to General Raffaele Cadorna (1815-1897) in Verbania. At age ten he entered the military school Teuliè in Milan; five years later he was sent to the Turin Military Academy. Cadorna had his “baptism by fire” when, shortly after he became second lieutenant, he participated in military operations against Rome in 1870. When he was thirty-nine, he married Maria Giovanni Balbi (1860-1941), member of the family of Marquis Balbi of Genova. They had a son whom they named Raffaele Cadorna, Jr. (1889-1973) in honor of his grandfather. As colonel, Cadorna commanded the 10th Regiment of Bersaglieri from 1892. Cadorna became famous for his strict discipline and harsh punishment. He also wrote a manual on infantry tactics, which emphasized the doctrine of the offensive. This doctrine would become the basis of the tactics he adopted during the Great War. In 1898 he was promoted to lieutenant general.

Cadorna finally achieved success in 1907 when he obtained command of Naples’ military division. Three days after the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria-Este (1863-1914) in Sarajevo, the Italian army chief of staff, General Alberto Pollio (1852-1914) died suddenly of a heart attack.

On 27 July 1914, Vittorio Emanuele III, King of Italy (1869-1947) named Cadorna army chief of staff and supreme commander, just three days before the Austro-Hungarian Empire gave its ultimatum to Serbia.

The War↑

Cadorna’s first challenge was to reorganize the army. In 1914 it was clear that the Italian military forces were unprepared for war, so the general dedicated the first few months of his assignment to strengthening and modernizing the army.

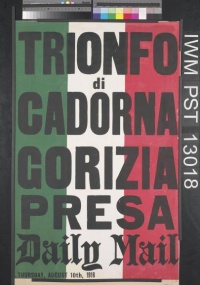

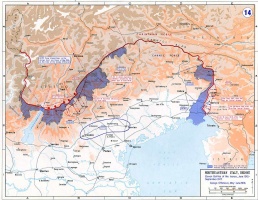

After the declaration of neutrality, Cadorna requested to start a general mobilization in order to prepare a stronger army, but the government rejected his proposal, fearing that it would accelerate entry into the war. The general’s strategy was to engage Austro-Hungarian troops in combat as frequently as possible; he concentrated many of the forces available in Friuli and opted for one defensive line in the Trentino region. Cadorna’s faith in his tactics never wavered, despite the lack of progress or the alarmingly high casualties.

Cadorna’s leadership style was influenced by a sense of duty. He sacrificed everything to the cause of victory; soldiers’ needs were absolutely secondary. This concept of duty was combined with his inability to understand the needs of a mass army composed of millions of men more or less prepared for war. The principles and application of a grueling discipline involved a serious neglect of the soldiers’ emotional and material needs. Inevitable failures were promptly and severely punished. These mistakes made Cadorna increasingly paranoid about an alleged defeatist maneuver.

Another crucial aspect of Cadorna’s leadership was his conviction concerning the “unity of command” – he placed great importance on a strict hierarchy. To the general, this dogma entailed his own absolute responsibility for the army; no one was allowed to contradict his authority. This led to his total isolation. These attitudes deeply influenced Cadorna’s relationship with the government. According to the general, the civil authorities had to accommodate the army’s every request without objection. If a clear separation of civil and military powers had been advocated and implemented before the war, the war’s onset made this separation increasingly difficult to maintain. The slowness of Italian politics favored the broadening of the army’s influence. Furthermore, Cadorna did not tolerate interference of any sort in war operations. The tense atmosphere and lack of mutual confidence led the government to decide to replace Cadorna, a decision which was finally confirmed by the defeat of October 1917.

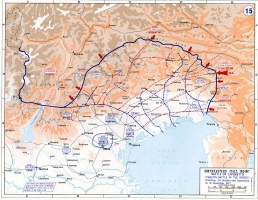

The absence of direct contact with the troops as well as a lack of a truly efficient information service exacerbated the commander-in-chief’s inability to ensure the prompt execution of his orders. This latter aspect was a crucial factor in the defeat in October 1917. Although Cadorna had been alerted several times about a possible Austrian attack on the Isonzo front, he was halfhearted in issuing orders and monitoring their execution. The army had to settle on defensive positions, but this order was only executed a few days before the Austrian offensive. On 24 October 1917, the Twelfth Battle of the Isonzo began, better known as the Battle of Caporetto. It represented the worst defeat ever suffered by the Italian army.

Final Years↑

Cadorna never admitted his responsibility for the defeat, instead accusing his troops of cowardice. The government fired him from the post and replaced him with General Armando Diaz (1861-1928). Cadorna, however, was appointed a member of the Allied Supreme War Council of Versailles, only to be retired as a result of the investigation into the Battle of Caporetto.

Luigi Cadorna served as senator from 1913 to 1928 but never adhered to fascism. He died on 21 December 1928 in Bordighera.

Anna Grillini, University of Trento and Italian-German Historical Institute

Section Editor: Marco Mondini