Introduction↑

Recognizing mourning and bereavement as relevant topics for historical analysis was a groundbreaking achievement in the humanities. Thinking “about loss as constituting social, political, and aesthetic relations” surpassed the conventional understanding that it “belongs to a purely psychological or psychoanalytic discourse.”[1] Scholars who analyzed the commemoration of war dead and examined the kin and community’s responses to state proclamations and initiatives recognized public grieving as a paradigmatic case study crucial to understanding social dynamism and the identity-making process.[2]

In South East Europe, numerous similarities in the commemoration practices to other European regions have been and continue to be identified. Simultaneously, complex historical and cultural features exist.[3] Differences in the reactions of local, religious, ethnic, gender and class communities as compared to official narratives reveal the ulterior heterogeneity of the post-war societies. Consequently, individuals and their primary communities have emerged as the final recipients of the official messages and simultaneously as the main creators of every local initiative. Shedding light on the work of those “agents of remembrance,” Jay Winter’s term for subjects in “the memory making process,” proved that “remembrance is a process with multiple voices” which “are rarely harmonious and never identical.”[4] Small social and local groups facing the loss of their loved ones created numerous practices of commemoration even before the war had ended. Their spontaneously expressed grief guided public post-war social and cultural actions. The official imposition of political ideas and different forms of their representation were fluid, often questioned, opposed or rejected by “memory activists.”

This article examines how the emotional bonds between mourners and memory activists, which produced the framework for expressing grief, were transposed to the wider society and intertwined with official state initiatives aiming to unite different mourning communities. The first section highlights the Balkan’s position during the First World War. The second part analyzes the complex relations between the traditional modes of bereavement and the newly invented forms of grieving after the First World War, as millions of mourners dealt with the absence of the fallen soldiers’ bodies. The last section discusses how military cemeteries and unknown soldiers’ graves shaped the image of the war and consequently influenced the formation of new individual and collective identities.

Death and Remembrance↑

Decade of War↑

Armistice Day did not represent the end of four years violence in the region of South East Europe. Characterized as “peripheral conflicts,” war atrocities both preceded the Great War’s onset and continued after the peace treaties were signed. In the north of the region, the borderlands between the former Russian and Austro-Hungarian Empires were the stage for inter-ethnic hostilities and revolutionary unrest until 1922. During the same period in the south, the Greco-Turkish conflict represented the final episode of a centuries-long Ottoman retreat from Europe. Taken together with the Balkan Wars in 1912–13 and the atrocities in 1921–22, the Great War marked the most important stage in the complex process of national homogenization.[5] It wiped off the map three empires, which for centuries had framed Balkan nations and ethnicities, and introduced new political realities welcomed by the allies: a new Yugoslav state (The Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes), enlarged Romania, restored Bulgaria, reunited Albania, and revolution-born secular Turkey.[6]

Elites in states formed after the Great War pushing for societal unification delt with a variety of religious legacies and historical traditions. The collective amalgamation process was gradually imposed from top to bottom. However, during these two interwar decades the heterogeneous Balkan states were “not as strong, and certainly not as able, to control cultural practices linked to nationalism as others have assumed by focusing too closely on developments in … capitals without considering events in more remote areas.”[7] Annexed territories in the majority of states were considered as margins requiring harmonization with the center. By uniting communities grieving over soldiers who fought on opposing sides during the war, states intended to include all citizens within a single national framework. Victorious discourse nonetheless slowly marginalized and excluded fallen enemy soldiers from dominant war narratives. Relevant only in the private sphere within their local communities, the commemoration of fallen soldiers with different ethnic and religious backgrounds occasionally sparked political tension and instability.

Nevertheless, traditional ethnic and religious communities were not the only ones whose viewpoints on war were relegated to the periphery. Shortly after the war, thousands of demobilized soldiers joined deserters who fled the Austro-Hungarian army. Many of those returning from Soviet Russia, where they spent years as prisoners of war, were impressed by communist ideas and the first proletarian state. Some of the industrial workers formed a distinctive group, which adopted the new ideas of collective unity and identity based on social, rather than national, grounds. The October Revolution and Béla Kun’s (1886-1939) republic in Hungary influenced public opinion in neighboring countries. “Growing alienation of the working class,” recognizable “in the course of social and political unrest” during the first post-war years, was articulated in regional political life mainly through the activities of Communist parties.[8]

Private Pain and Public Grief↑

At the beginning of the 20th century, the fallen soldier symbol created image of wars as specific “signatures of history,” around which social stability was to be structured through innumerable commemorational practices.[9] Its significance became entirely apparent after the Great War, when human losses changed generational and gender balances in Europe. The need to mourn publicly resulted from the overwhelming pain and grief and the fact that the majority of survivors could not bury their loved ones. Although epidemics and famine claimed millions of civilian lives during the war, they were rarely commemorated in public. Even the tragedy of those killed during punitive expeditions seemed less important. Civilian casualties remained relegated to the margin of public awareness. Two sculptures commemorating civilian war victims by the Serbian sculptor Đorđe Jovanović (1861-1953) were among the rare symbols of the suffering of those not mobilized during the war. Instead, war survivors focused their grief on those community members who died in uniform. Most lost their lives far from home and their bodies remained thousands of kilometers away. Since the proper burial of a loved one was connected to specific practices linked to the body itself, from washing to clothing, many families quickly realized that they needed to find new ways of honoring tradition while dealing with the brutal reality of the disappearance of the loved one far away from home, in lands that were hard for the family to imagine.[10]

The survivors’ need for a place to mourn and to share condolences with other community members was genuinely deprived of ideological function. During the commemorative practice relatives practically revived their dead. The survivors’ anxiety was replaced by public mourning as “the regulated and socially controlled expression of individual feelings of grief.”[11] Fearing that the body’s absence could produce “the loss of loss itself” and that in the future “no story [could] be told about it; no memory [could] retrieve it,” traditional communities produced specific social practices by which “the irrecoverable [became], paradoxically, the condition of a new political agency.”[12] Public manifestations of pain and shared condolences represented the way to face and overcome the loss.

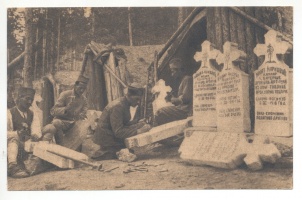

Expressed sentiments influenced further development of a specific practice of the preservation of dead ancestors’ names. After the Great War, families in Romania, for instance, erected wooden crosses, decorated with folk art motifs, in churchyards for those whose remains were lost.[13] Many believed that “not being able to have a proper burial rendered those soldiers victims again, this time as human beings and Orthodox Christians in particular, who would thus be denied passage into the afterlife, despite their sacrifice.”[14] In Serbia, stone markers one to two meters high were raised next to the roads in the vicinity of fallen warriors’ homes, with details concerning the life and death of dead soldiers to passersby. The stones were sometimes made in the shape of a cross and often colorfully decorated with extensive textual inscriptions. In the mid-1960s these roadside monuments were named “krajputaši” (roadside monuments, or roadsiders)[15]

Besides the aforementioned examples of commemorations held by the close relatives, small local communities (primarily in Yugoslavia and Romania) organized steering committees to coordinate the long and complex process of erecting public monuments. Built in almost every village and town and inscribed with the names of the missing, local monuments helped relatives overcome grief. The committees were in continuous communication with state officials to obtain permission for the monuments or to gather design ideas. In most cases, monuments were built with community money and maintained by its members.

The monuments erected during the first post-war decade represented local communities’ spontaneous actions. In victorious states, they were always erected in central squares and main streets, enabling attendance by a majority of citizens at the commemorative ceremonies. Monuments to the fallen from the army of the vanquished Austro-Hungarian Empire were erected mostly in local cemeteries and churchyards.[16] For example in Slovene-speaking territories, which became part of the Yugoslav state, local communities created numerous monuments and memory plaques to commemorate fallen soldiers in the Imperial and Royal (k. und k.) army often implying their commitment to unification of the South Slavs.[17]

In Bulgaria, one of the defeated states, the case was somewhat different. Initially “spontaneous mass construction of soldiers’ statues in towns and villages across the country nuanced by municipalities, relatives of the dead and donations from ‘Bulgarian patriot emigrants in distant countries’” was abandoned. Oddly enough, this memorializing activity also occasioned a debate that resulted ultimately in a prohibition against memorials to those who had died in the wars of national unification (that is, the Balkan Wars of 1912–13 and the Great War) being consecrated as monuments “to the unknown warrior” because of the possible connotations of “forgetfulness, abundance and depersonalization.”[18]

Over time, grief and its stages of denial, numbness, anger, sadness and depression were overcome. The individuals recovered and their acceptance of the loss prevailed. Memories were reshaped and their bearers incorporated the void in their personal and collective identities. Dead neighbors and relatives were added to the long list of national heroes and martyrs. The symbol of war tragedy became the symbol of pride and even arrogance. Memories were wrapped in national colors. In Yugoslavia and Romania, colossal memorials erected in the 1920s and 1930s soon became the key national symbols. At the same time in Bulgaria, blurring memories testified to a completely different remembrance politics constructed to suppress or even erase memories of the Great War, a symbol of its greatest political failure. In Greece and Albania, on the other hand, prevailed political and social neutrality, occasionally even ignorance over the war episodes and its participants.[19]

Safeguarding the Dead↑

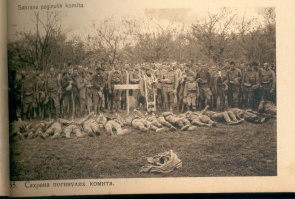

During the Great War, army officials were responsible for organizing soldiers’ funerals and regulating military cemeteries. Due to the fact that war hostilities prevented their work, bodies were often left in combat zones, forgotten behind enemy lines, even abandoned to rot in the trenches. Fear of death and of the dead bodies’ desecration and mutilation was a source of constant anxiety among combatants.[20] Military graveyards near the frontlines represented soldiers’ and commanders’ first attempts to pay their respect to the dead. Burial was seen as the main duty of those who survived.

Burial rites always had an important social function in strengthening ties and fostering emotional bonding between group members. This was why funeral rituals were recommended to officers “as a means of disciplining the troops and cultivating a respectful attitude.”[21] According to the Bulgarian psychologist Spiridon Kazandzhiev (1882-1951), this “...[served] the therapeutic purpose of relieving or preventing the development of the taboo thought amongst the combatant that he might ‘die as a dog, forgotten by everybody.’”[22]

Military officials recognized this paradigm change and introduced the new practice all over Europe.[23] Nevertheless, it further complicated the relationship between soldiers in multinational armies like the Austro-Hungarian one. One Romanian officer in the k. und k. army recounted in his memoirs an especially disturbing moment, in which his Romanian soldiers were buried under a cross with the German and Hungarian text: “Soldiers dead for the fatherland from the k. und k. Rupprecht Gronprinz v. Bayern, no. 43 Regiment.”[24]

The new practice of erecting military cemeteries was internationally recognized in the peace treaties and accepted by national states’ corresponding laws. All these documents included special sections concerning military graves and graveyards, which precisely defined each state’s responsibility and authority in maintaining the cemeteries regardless of soldiers’ national or religious origin and affiliation. However, before the treaties were signed and state officials obliged to take care of the cemeteries, some local populations expressed their mourning at the graves of, to them, unknown soldiers. “If mothers, fathers, wives, and daughters could not retrieve the bodies of loved ones, they could at least honor them by retrieving bones of others who had died in the war.”[25]

In the cemeteries, dead soldiers were divided in separate sections according to army membership, but never by rank. Furthermore, some ossuaries contained collections of bones not separated by the side they had fought on. Their tragic participation in what was believed to be the worst war in history was perceived to be the most important fact in their lives and they were all commemorated regularly every 11 November.

Conclusion↑

The Great War in South East Europe had many particularities. It was not only the war of position, in which the front lines were constant. Military offensives and retreats, occupation, long marches and partisan fighting characterized the whole period. Mass killing, expulsions, ethnic migrations and resettlements, as well as widespread epidemics, changed the population structure and transformed entire cultural landscapes. In that respect, the death toll changed not only the funeral practices, but also communal identities. The fact that almost every village and town erected countless individual gravestones, memory marks and memory plaques, often containing long lists of the names of the fallen soldiers, reshaped the landscape and introduced new forms of community gatherings. United in grief, they created an image of the war that gave meaning to their beloveds’ deaths. The primal need of an individual to mourn in silence was suspended by the loss of the body and the consequent inability of relatives to pay respect to the dead through traditional rituals. The same experience of loss brought thousands of people closer together. Instead of individually erecting mnemonic objects, “community activists” initiated construction of common memorials based on the newly introduced practice of listing the fallen soldiers’ names.

As specific shrines, those places of memory and the commemoration ceremonies held in front of them represented constitutive elements of the new communal bonding. Whether in complete unity or in direct collision with the official narratives and symbols, local communities challenged the processes of individual and collective identity creation and transformation. One could argue that through their remembrance of the dead, the living created their present.

Olga Manojlović Pintar, Institute for Recent History of Serbia

Section Editors: Richard C. Hall; Milan Ristović; Tamara Scheer

Notes

- ↑ See: Butler, Judith: Afterword. After Loss, What Then?, in: Eng, David L./Kazanjian, David (eds.): Loss. The Politics of Mourning, Berkeley et al. 2003, pp. 467–73.

- ↑ Fussell, Paul: The Great War and the Modern Memory, London 1977; Hobsbawm, Eric/Ranger, Terence: The Invention of Tradition, London 1983; Mosse, George L.: Fallen Soldiers. Reshaping the Memory of the World Wars, Oxford et al. 1990; Le Goff, Jacques: History and Memory, New York 1992; Winter, Jay: Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning. The Great War in European Cultural History, Cambridge 1995.

- ↑ Todorova, Maria: Imagining the Balkans, New York 1997; Bucur, Maria: Heroes and Victims. Remembering War in Twentieth-Century Romania, Bloomington et al. 2010; Bokovoy, Melissa: Scattered Graves, Ordered Cemeteries. Commemorating Serbia’s Wars of National Liberation, 1912-1918, in: Bucur, Maria/Wingfield, Nancy (eds.): Staging the Past. The Politics of Commemoration in Habsburg Central Europe, West Lafayette 2001, pp. 236–54; Dimitrova, Snezhana: ‘My War is not Your War.’ The Bulgarian Debate on the Great War ‘The experienced war’ and Bulgarian modernization in the inter-war years, in: Rethinking History. The Journal of Theory and Practice 6/1 (2002), pp. 15–34.

- ↑ Winter, Jay M.: Remembering War. The Great War between Memory and History in the Twentieth Century, New Haven 2006, p. 136.

- ↑ Hall, Richard C.: The Balkan Wars 1912-1913. Prelude to the First World War, New York 2000.

- ↑ Mitrović, Andrej: Serbia’s Great War, 1914-1918, London 2007. The death toll in the Balkans far surpassed other regions of Europe: “The top four countries with the highest percentage of dead from among the men who served anywhere in Europe were all from the Balkans – Serbia (37 percent), Turkey (27 percent), Romania (26 percent) and Bulgaria (23 percent)...The war was more destructive in the East than in the West: even before counting the Habsburg and Italian casualties, over six million civilians died in the East, while less than fifty thousand did in the West.” Bucur, Heroes 2010, p. 51.

- ↑ Bucur, Maria: Of Crosses, Winged Victories, and Eagles. Commemorative Contests between Official and Vernacular Voices in Interwar Romania, in: East Central Europe 37 (2010), pp. 31–58, especially p. 55.

- ↑ Kramer, Alan: Dynamic of Destruction. Culture and Mass Killing in the First World War, Oxford 2007, p. 310.

- ↑ Butler, Afterword 2003, p. 468.

- ↑ Bucur, Of Crosses 2010, p. 53.

- ↑ Bourchier, Christine: Rituals of Mourning. Bereavement, Grief and Mourning in the First World War, issued by University of Calgary, online: http://grad.usask.ca/gateway/archive13.html#9 (retrieved: on 20 October 2012)

- ↑ Butler, Afterword 2003, p. 467.

- ↑ Butler, Afterword 2003, p. 38.

- ↑ Bucur, Heroes 2010, p. 55.

- ↑ Radičević, Branko V.: Seoski nadgrobni spomenici i krajputaši u Srbiji [Rural Tombstones and Roadsiders in Serbia], Belgrade 1965.

- ↑ Špelca Čopič, Slovenski spomeniki padlim v Prvi svetovni vojni [Slovenian monuments to the fallen in the First World War], in: Kronika,Časopis za Slovensko krajevno zgodovino [Chronicle. Journal of Slovenian local history], no. 35, 1987, pp. 168–77.

- ↑ Only two monuments and memory plaques were erected in the Italian territory inhabited by the Slovenians. See: http://www.arzenal.si/sobe/zbirke/spomeniki, (retrieved: on 20 October 2012)

- ↑ Dimitrova, ‘My War’ 2002, p. 24.

- ↑ With the national revival in many South East European societies at the end of the 20th century, many WWI monuments returned to the center of public interest. See: Pintar, Olga Manojlović: Tradicije Prvog svetskog rata u Srbiji, Od simbola sanjanog jugoslovenstva, do simbola izneverenog srpstva [The Traditions of the First World War in Serbia. From the Symbol of Dreamed Yugoslavism, to the Symbol of Betrayed Serbianhood], in: Cipek, Tihomir/Milosavljević, Olivera (eds.): Kultura sjećanja, Povijesni lomovi i svladavanje prošlosti [Culture of Remembrance, Historical Breaks and Overcoming the Past], Disput, Zagreb 2007, pp. 155–67; Luthar, Breda / Luthar, Oto: Kolonizacija spomina, Politika in tekstualnost domobranskih spomenikov po letu 1991 [Colonization of Memory, Politics and Textuality of the Home-guard Monuments since 1991], in: Perovšek, Jurij / Luthar, Oto (eds.): Zbornik Janka Pleterskega [Janko Pleterski’s Compendium of Works], Ljubljana 2003, pp. 647–64.

- ↑ Dimitrova, Snezhana: ‘Taming the death.’ The culture of death (1915-18) and its remembering and commemorating through First World War soldier monuments in Bulgaria (1917-44), in: Social History 30/2 (May 2005), pp. 175–94.

- ↑ Dimitrova, ‘My War’ 2002, p. 24.

- ↑ Dimitrova, ‘My War’ 2002, p. 24.

- ↑ Lacquer, Thomas W.: Memory and Naming in the Great War, in: Gillis, John R. (ed.): Commemorations. The Politics of National Identity, Princeton 1994, p. 152.

- ↑ Bucur, Heroes 2010, p. 55.

- ↑ Bucur, Heroes 2010, p. 56.

Selected Bibliography

- Bokovoy, Melissa: Scattered graves, ordered cemeteries. Commemorating Serbia’s wars of national liberation, 1912-1918, in: Bucur-Deckard, Maria / Wingfield, Nancy M. (eds.): Staging the past. The politics of commemoration in Habsburg central Europe, 1848 to the present, West Lafayette 2001: Purdue University Press, pp. 160-181.

- Bucur-Deckard, Maria: Heroes and victims. Remembering war in twentieth-century Romania, Bloomington 2010: Indiana University Press.

- Bucur-Deckard, Maria: Of crosses, winged victories, and eagles. Commemorative contests between official and vernacular voices in interwar Romania, in: East Central Europe 37/1, 2010, pp. 31-58.

- Dimitrova, Snezhana: Taming the death. The culture of death (1915-18) and its remembering and commemorating through First World War soldier monuments in Bulgaria (1917-44), in: Social History 30/2, 2005, pp. 175-194.

- Dimitrova, Snezhana: My war is not your war. The Bulgarian debate on the Great War, 'the experienced war' and Bulgarian modernization in the inter-war years, in: Rethinking History 6/1, 2002, pp. 15-34.

- Fussell, Paul: The Great War and modern memory, Oxford 2013: Oxford University Press.

- Hobsbawm, E. J. / Ranger, T. O.: The invention of tradition, Cambridge; New York 1983: Cambridge University Press.

- Ignjatović, Aleksandar: Architecture, urban development, and the Yugoslavization of Belgrade, 1850–1941, in: Centropa IX/2, 2009, pp. 110–126.

- Knežević, Jovanna Lazić: The Austro-Hungarian occupation of Belgrade during the First World War. Battles at the home front, New Haven 2006: Yale University Press.

- Kramer, Alan: Dynamic of destruction. Culture and mass killing in the First World War, Oxford; New York 2007: Oxford University Press.

- Lacquer, Thomas: Memory and naming in the Great War, in: Gillis, John R. (ed.): Commemorations. The politics of national identity, Princeton 1994: Princeton University Press, pp. 150–168.

- Mitrović, Andrej: Serbia's Great War, 1914-1918, West Lafayette 2007: Purdue University Press.

- Mosse, George L.: Fallen soldiers. Reshaping the memory of the world wars, New York 1990: Oxford University Press.

- Stoianovich, Traian: Balkan worlds. The first and last Europe, Armonk 1994: M.E. Sharpe.

- Todorova, Maria: The trap of backwardness. Modernity, temporality, and the study of Eastern European nationalism, in: Slavic Review 64/1, 2005, pp. 140-164.

- Todorova, Maria: Imagining the Balkans, New York 1997: Oxford University Press.

- Turcanu, Florian: Roumanie, 1917-1920. Les ambiguïtés d’une sortie de guerre, in: Audoin-Rouzeau, Stéphane / Prochasson, Christophe (eds.): Sortir de la Grande Guerre. Le monde et l'après-1918, Paris 2008: Tallandier, pp. 237–256.

- Winter, Jay: Remembering war. The Great War between memory and history in the twentieth century, New Haven 2006: Yale University Press.

- Winter, Jay: Sites of memory, sites of mourning. The Great War in European cultural history, Cambridge 2000: Cambridge University Press.