Breaking up the Habsburg Empire↑

Conspiracy: The Maffie↑

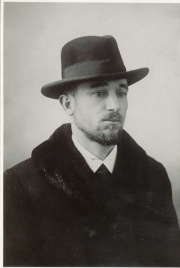

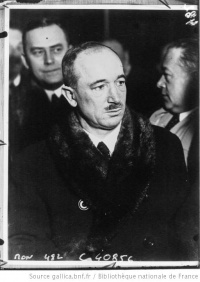

Edvard Beneš (1884-1948), then a sociology teacher and lecturer in the Prague Academy of Commerce at the Charles University, was one of the main organizers of the anti-Habsburg conspiracy of Czech politicians in 1915. This conspiracy was called - with intended irony - Maffie, or “Mafia.” Its couriers kept Tomas Garrigue Masaryk (1850-1937), then in exile in Switzerland, in contact with important Czech politicians, enabling him to influence politics at home. These couriers also delivered reports on the situation in Austria-Hungary. At the time, Beneš was a virtually unknown young academic and unorthodox (non-Marxist) socialist journalist who shared some of the ideas of Masaryk’s small Realist Party. He had been writing for Masaryk’s periodical Čas (Time) since 1914. He had also lent money to finance Masaryk’s activities abroad, and then joined Masaryk in trying to undermine Austria-Hungary and achieve Czech independence.

Revolution from Abroad: Propaganda, Funds, and Troops↑

In September 1915, Beneš followed Masaryk into exile. Masaryk’s hopes that prominent Czech politicians would leave Bohemia and join him had been dashed, and he could not organize revolution from abroad single-handedly. As Masaryk settled in London and worked to win over British journalists, government, and political circles for the Czech(oslovak) cause, Beneš did the same in Paris. He wrote articles for major newspapers like Le Matin or Journal des Débats, lectured at the Sorbonne, and wrote memoranda and letters to influential figures. He also tried to influence lower officials of various ministries, especially Foreign Affairs and War and Munitions; to the latter, he passed confidential Maffie reports on the political, economic, and military situation in Austria-Hungary. In his efforts, he was aided by his contacts from his student years in Paris, such as university professors Louis Eisenmann (1869–1937) or Ernest Denis (1849–1921), and various socialist journalists (as a student he had worked as a correspondent for Czech socialist newspapers).

While Masaryk was the undisputed leader of the Czechoslovak Foreign Committee (established in February 1916), Secretary General Beneš coordinated its activities. The main tasks were propaganda, fundraising, and negotiations to establish Czechoslovak armed forces (called Legions) consisting of Czech and Slovak prisoners of war. Milan Rastislav Štefánik (1880–1919), a Slovak officer serving in the French Army and well-connected in Paris’s upper class, proved instrumental in lobbying efforts. Masaryk and Štefánik spent many months in the United States and in Russia during 1917 and 1918, while Beneš worked from Paris. He occasionally traveled to London or Rome, where he opened Czech press bureaus and co-organized an anti-Habsburg Congress of Oppressed Nations in April 1918. His efforts to urge Czech and Slovak communities abroad to contribute to the Czechoslovak cause and to urge prisoners of war to enlist in the Czechoslovak Legions succeeded. Beneš eventually convinced the Allies that destroying Austria-Hungary would further their own interest and prevent future German attempts to dominate Europe. Masaryk and Beneš depicted the Czechoslovak nation as progressive and democratic, and engaged in a centuries-long struggle against German, Hungarian, and Habsburg oppression. This image was meant to strengthen their claims of the Czechs’ and Slovaks’ right to self-determination as declared by American President Woodrow Wilson (1856–1924), and to prove ideological affiliation to the Entente.

Diplomacy and Peacemaking↑

Masaryk, Beneš, and Štefánik correctly assumed that the Allies’ diplomatic recognition of the provisional Czechoslovak government would only follow after the recognition of independent Czechoslovak troops on the French, Russian, and Italian fronts. This recognition was realized in 1917 in Russia: after the October Revolution, the Czechoslovak Legions’ temporary control of the Trans-Siberian Railway provided the Entente powers with a potential means of influencing the Russian civil war. The Czechoslovak National Council, to whom the Legion in Russia looked for guidance, managed to translate this development into a political advantage. On 7 February 1918, Beneš and Georges Clemenceau (1841–1929) signed a treaty defining the Czechoslovak troops in France as an independent national army, politically and judicially subordinate to the National Council. Recognitions of Czechoslovak troops in Russia and Italy soon followed.

On 28 June and 9 August 1918, Beneš achieved, respectively, French and British recognition of the National Council as a nucleus of a future Czechoslovak government. On 14 October 1918, the National Council declared itself a provisional government consisting of Masaryk (Prime Minister, Finance), Beneš (Foreign Affairs, Interior), and Štefánik (War). It was immediately recognized as such by the Allies.

In a high point of his diplomatic career to that point, Beneš was the only foreign minister of a new state to sign the armistice conditions on 11 November 1918. As the informal head of the Czechoslovak delegation at the Paris Peace Conference, he was able to put through nearly all of Czechoslovakia’s territorial claims, including Slovakia and the Carpathian Ukraine. Masaryk hardly exaggerated when he stated in 1929, during a political controversy over resistance abroad and home, that Czechoslovakia would not exist without Beneš. For many defeated and revisionist Germans and Hungarians, however, Beneš embodied the real or alleged injustice and territorial losses imposed on them.

Aftermath and Perception↑

As Czechoslovakia’s Foreign Secretary from 1918 to 1935 and subsequently its second president, Beneš worked to preserve the postwar political order established by the Paris Peace Treaties, especially within the framework of the League of Nations. In 1938, the Munich Agreement marked his failure, but in his second exile, from 1938 to 1945, he was able to achieve the restoration of Czechoslovakia. His role in the expulsion of the German minority from Czechoslovakia after the Second World War, his disputed part in the pro-Soviet orientation of the country after 1943, and his responses to the Munich crisis in 1938 and to the communist coup d’état in 1948 have made him a controversial figure through the present day - in the Czech and Slovak Republics as well as internationally.

René Küpper, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität

Section Editor: Tamara Scheer

Selected Bibliography

- Beneš, Edvard: Světová válka a naše revoluce. Vzpomínky a úvahy z bojů za svobodu národa (The World War and our revolution. Memories and reflections of fighting for the freedom of the nation), 3 volumes, Prague 1927: Orbis a čin.

- Dejmek, Jindřich: Edvard Beneš. Politická biografie českého demokrata (Edvard Beneš. A political biography of the Czech democrat), 2 volumes, Prague 2006: Karolinum.

- Konrád, Ota / Küpper, René (eds.): Edvard Beneš. Vorbild und Feindbild; politische, mediale und historiographische Deutungen, Göttingen 2013: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Orzoff, Andrea: Battle for the castle. The myth of Czechoslovakia in Europe, 1914-1948, New York 2009: Oxford University Press.

- Šolle, Zdeněk (ed.): Vzájemná neoficiální korespondence T. G. Masaryka s Edvardem Benešem z doby pařížských mírových jednání (říjen 1918 - prosinec 1919), 2 volumes, Prague 1994: Archiv Akad. Věd ČR.