Early Life↑

Gertrude Margaret Lowthian Bell (1868-1926) was born in Washington New Hall, the estate of her grandfather and famous iron magnate Sir Isaac Lowthian Bell (1816-1904). Gertrude Bell rejected a mere life of comfort at an early age, and would ultimately become one of the most influential figures in the development of British imperial rule in the Middle East. She leveraged her social and economic privilege to pursue an education, eschewing her society’s expectations about women in her position. After attending Queen’s College in London, Bell joined Oxford University’s Lady Margaret Hall in 1886. She graduated two years later, becoming one of the first women to receive a first class honours degree from Oxford in modern history.

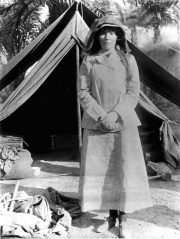

Travels in the Middle East↑

Bell’s family wealth allowed her to travel extensively. She capitalized on this to pursue her intellectual interests and desire for adventure, becoming one of the first “solo” female Western travellers in the Middle East. Her fascination with the region can be traced back to 1892, when she travelled to Tehran to visit her uncle Frank Lascelles (1841-1920), the British ambassador to Persia. Two years later, Bell published her first book, Safar Nameh, Persian Pictures, a travelogue of her time in Persia. Bell would spend much of the following two decades traveling in the Middle East, visiting sites of antiquity in Syria, Palestine, and Mesopotamia, and publishing classic works of travel writing, including The Desert and the Sown (1907) and Ammurath to Ammurath (1911).

Bell returned to southern Mesopotamia in 1911 to photograph and survey the fortress of Ukhaidir, resulting in the 1914 book The Palace and Mosque of Ukhaidir: A Study in Early Mohammadan Architecture, considered by historians today as one of her most important scholarly contributions to archaeology. In The Desert and the Sown, Bell described the inextricable link between her travels and information gathering, presenting herself as a reporter of “what falls from the lips of those who sit round our camp fires, and who ride with us across desert and mountains, for their words are like straws on the flood of Asiatic politics, showing which way the stream is running.”[1] By the start of the First World War, Gertrude Bell had established herself as an authority in the history of the Middle East and Anglophone travel writing, fields overwhelmingly represented by men at that time.

“Queen of the Desert”↑

By November 1914, Gertrude Bell had begun volunteering with the Red Cross at the ad hoc Clandon Park Hospital, and within a few weeks managed to secure a new post at the organization’s headquarters in Boulogne, France. A year later, David Hogarth (1862-1927) – citing Bell’s pre-war travels and expertise of the region – invited her to Cairo to join the nascent Arab Bureau, a British information gathering and espionage organization. Gertrude Bell was the only female political officer across the entire foreign office’s operations. Chief among the bureau’s objectives were the coordination of support for the 1916 Arab Revolt and the dissemination of pro-British propaganda throughout the Muslim world. Bell’s work included authoring reports in the Arab Bulletin, the bureau’s clandestine periodical. In early 1916 Bell served as a liaison between the bureau and the India Office, and while in Delhi she agreed to work as an editor of the Gazetteer of Arabia, a compendium of geographical and ethnographic reports compiled by British intelligence agents across the empire. She then travelled to Basra to head a new branch of the Arab Bureau there, and in June began working in the political office of the Indian Expeditionary Force D, headed by Sir Percy Cox (1864-1937).

Bell cultivated a reputation as an Arab expert and made herself indispensable to the administration of Iraq during and after the war; in the words of one colleague, Bell “knew the Arabs more intimately than any other member of the civil staff.”[2] After the British capture of Baghdad in March 1917, Bell continued to work with Sir Percy Cox, albeit under a new title: “oriental secretary”. At the request of the War Office, she anonymously published The Arab of Mesopotamia (1917), an anthology of ethnographic reports and historical essays, as well as guidebooks for soldiers on the ground.

As oriental secretary, Bell published a number of memoranda advocating for a degree of Iraqi self-determination in the form of an Arab government under British control. In 1920 she authored the white paper Review of the Civil Administration of Mesopotamia, outlining her recommendations for the structure and administration of a future Iraqi state. She attended the Cairo Conference of 1921 – the only woman participating as a delegate – where she advocated for naming Faisal bin Hussein (1883-1933) as the first king of Iraq. Bell would serve as an advisor and confidant to Faisal for the remainder of her life.

By 1921, Gertrude Bell and Percy Cox were leading advocates for indirect administration and Arab “self-determination” as understood at the time: limited self-rule within the confines of a British imperial framework. This position contrasted sharply with the views of Arnold Wilson (1884-1940), the civil commissioner in Baghdad from 1918-1920, who advocated for direct colonial rule in Iraq. Ultimately Bell’s vision of mandatory rule prevailed and shaped British administration across the region. Her influential work in establishing the modern Iraqi state continues to receive both praise and criticism from historians today.

Bell’s Legacy↑

From the end of World War I to her death in 1926, Gertrude Bell reignited her interest in archaeology, serving as Iraq’s honorary director of antiquities and drafting the country’s antiquities legislation in 1924. Some historians have praised Bell’s legislation for laying the groundwork for Iraqi heritage preservation, while others have criticized the law’s concessions for exporting antiquities. She is also credited with establishing the Iraqi state’s first museum in the capital, as well as promoting the development of the Baghdad Peace Library, which would later become the National Library of Iraq. Gertrude Bell passed away on 11 July 1926 from an overdose of sleep medication. Debates continue as to whether the overdose was intentional or an accident.

Laith Shakir, New York University

Reviewed by external referees on behalf of the General Editors

Notes

Selected Bibliography

- Collins, Paul / Tripp, Charles (eds.): Gertrude Bell and Iraq. A life and legacy, Oxford 2017: Oxford University Press.

- Cooper, Lisa: In search of kings and conquerors. Gertrude Bell and the archaeology of the Middle East, London; New York 2016: I. B. Tauris.

- Lukitz, Liora: A quest in the Middle East. Gertrude Bell and the making of modern Iraq, London; New York 2006: I. B. Tauris.

- Satia, Priya: Spies in Arabia. The Great War and the cultural foundations of Britain's covert empire in the Middle East, Oxford 2008: Oxford University Press.

- Wallach, Janet: Desert queen. The extraordinary life of Gertrude Bell, adventurer, adviser to kings, ally of Lawrence of Arabia, New York 2005: Anchor Books.