Introduction↑

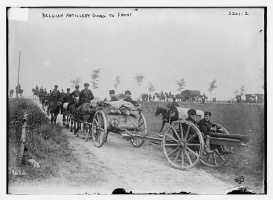

Belgium went to war with 200,000 men out of a male population of 3,680,790. 90 percent of them were draftees, civilians in uniform; the rest were professional soldiers or officers. Belgian soldiers were called Jass (the Dutch word for coat) or Piottes, both pre-war terms for draftees. Between 1915 and 1918 the army had an average strength of 137,000. In total some 320,000 men served in the Belgian Armed Forces. More conscripts reinforced the ranks during the hostilities (70,000 in total, mainly from the Belgian diaspora; one out of five Belgians became refugees in 1914). Some 50,000 war volunteers joined them, many of them escaped from occupied Belgium through the Netherlands. Among the latter were many bourgeois who gradually rose to the rank of junior officer.

Separated from the Home Front↑

The fate of the Belgian soldiers was in many aspects different from that of their French, British and German counterparts. First, they were separated from their loved ones in occupied Belgium, though it should be noted that the same goes for some of the French soldiers from the northern departments. A Belgian soldier could not return home when he was on leave. Instead he spent his holidays in France or Great Britain, an expensive journey. Non-profit organisations supported the poorest soldiers in making the trip. Like everywhere, letters and trench newspapers were subjected to military censorship. However, the Belgian military also had very little information about life on the home front. The rare news received was not reassuring since soldiers’ families were suffering under German occupation. Local news from home was immediately shared in the trench newspapers which had very strong regional and religious content. The rare opportunities of correspondence with the home front were slow and uncertain since all letters had to be smuggled over the Dutch-Belgian border.

Poor Living and Welfare Conditions↑

Second, the Belgian soldiers’ daily life in the rear zone was marked by several difficulties. Their pay was poor compared to French and British colleagues. They ate unhealthy and unbalanced food. Moreover, the Belgian army was very slow at organizing an official system of welfare, education, and entertainment. Only from 1917 on did the army start to take care of shops, sports competitions, education, libraries etc. Until then these activities had been a private initiative, mostly lead by organisations with catholic roots (e.g. study groups).

Casualties↑

Third, it’s important to stress that more than 40,000 Belgians died during the First World War despite a unique defensive military strategy. This represents a death rate of 12.5 percent. Belgian soldiers died at an average age of twenty-six years. In the trenches the harsh living conditions in flooded areas caused many diseases. One-third of all deadly casualties in trench warfare was due to illness (compared with one out of six for other belligerents.) Belgian army divisions spent nearly all their time on the frontline, whereas their German opponents or allied friends were often recalled for training and rest periods. Furthermore, 77,422 were wounded and hospitalized while 122,987 were hospitalized for illness. Some 41,000 Belgians were taken prisoner.

Belgian soldiers fought and died in their trenches on the front of the Yser River, north of the Ypres salient. In the first months of the war, they were also engaged in severe battles in Liège and Namur (August 1914) and around Antwerp (August-October 1914). The deadliest days of the war were 28 September 1918 (the first day of the Liberation Offensive; 1,036 dead) and 12 September 1914 (fighting around Antwerp; 893 dead).

Scarcity of Sources↑

Despite a literacy rate of more than 90 percent, only a limited number of published and unpublished memoirs and letters are available. So far, only partial quantitative and qualitative studies have been undertaken based on lists of casualties or judicial records. It is therefore impossible to form answers to general questions such as why did soldiers fight during the war. Only few Belgian historians have done innovative research on this topic and came to the conclusion that both consent (the war is right; the country in general and the home town in particular have to be liberated) and repression (fear of punishment) played an important role in the soldier’s thinking. Moreover, soldiers came from different social groups: the infantrymen, for instance, were composed of 25 percent farmers, 60 percent industrial workers and 15 percent traders. Therefore, a universal “Belgian soldier” simply did not exist.

Military Discipline↑

The war had an impact on military discipline. Due to the harsh living and fighting conditions in and behind the trenches, young officers and NCO’s were forced to live closer to their men than ever before. Imposing a rigid and formal discipline (as the army command wanted) was all but easy. Therefore, military discipline became more informal, based on mutual respect. Soldiers often “negotiated” successfully with their superiors to loosen the discipline by protesting individually or collectively. However, there were never mutinies or armed resistance. Twelve soldiers were executed: seven in 1914, three in 1915 and two in 1918. Two were sentenced to death for killing a superior; one who killed his pregnant girlfriend was guillotined on 26 March 1918.

The most important tension was between the Flemish (Dutch-speaking) soldiers and their French-speaking superiors. French was the overall command language. It was used for all orders, official publications and instruction trainings. This linguistic tension was increased by an overrepresentation of Flemish soldiers. 70 percent of the dead of 1915-1918 were Flemish, whereas they made up only 55 percent of the Belgian population in 1910.[1] This number and the discussion of whether Flemish soldiers paid a too high price compared to French-speaking Belgians, is still an issue today, in particular among Flemish nationalists. Some Flemish Catholics and intellectuals started a secret movement within the army, the Frontbeweging, that pressed for more linguistic rights for Dutch speakers. The movement garnered no fewer than 5,000 members. In 1917 and 1918, their frustration led to a series of demonstrations and riots in the rear zone. Red flags also appeared. High Command only made small concessions to the Flemish military, e.g. officers had to pass a (ridiculously easy) language test and official texts were translated into Dutch.

On the one hand, the Belgian soldiers suffered from the same poor living conditions and daily violence in the trenches. On the other hand, their fate was different than that of their British or German counterparts, e.g. the separation from their loved ones in occupied Belgium. The latter turned out to be an important factor of frustration and a good motivator at the same time.

Tom Simoens, Royal Military Academy

Section Editor: Emmanuel Debruyne

Notes

- ↑ De Vos, Luc and Keymeulen, Hans: Een definitieve afrekening met de 80%-mythe? [A final conclusion for the 80%-myth?], in: Belgisch Tijdschrift voor Militaire Geschiedenis [Belgian Journal for Military History] XXVIII/2 (1989), pp. 81-104.

Selected Bibliography

- Amez, Benoît: Dans les tranchées. Les écrits non publiés des combattants belges de la Première Guerre mondiale. Analyse de leurs expériences de guerre et des facteurs de résistance, Paris 2009: Publibook.

- Benvindo, Bruno: Des hommes en guerre. Les soldats belges entre ténacité et désillusion, 1914-1918, Brussels 2005: Archives générales du Royaume.

- Christens, Ria / De Clercq, Koen: Frontleven 14/18. Het dagelijkse leven van de Belgische soldaat aan de IJzer (Living at the front 14/18. Daily life of Belgian soldiers on the Yser River), Tielt 1987: Lannoo.

- De Vos, Luc / Simoens, Tom / Warnier, Dave et al.: 14-18. Oorlog in België (14-18. War in Belgium), Leuven 2014: Davidsfonds.

- Vanacker, Daniël: De Frontbeweging. De Vlaamse strijd aan de IJzer (The Front Movement. The Flemish struggle on the Yser river), Koksijde 2000: Klaproos.