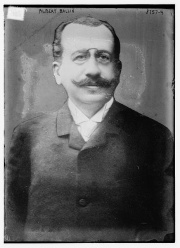

Self-Made Man↑

Albert Ballin (1857-1918) was born in Hamburg as the thirteenth child of a Jewish ticket broker who had moved to Hamburg from Denmark. In 1886 Ballin became the head of Hamburg-America Linie’s (HAPAG) passenger division. Together with the Bremen-based steamship line North German Lloyd, HAPAG established a de facto monopoly over the lucrative transatlantic passenger market in the Russian and Austro-Hungarian Empires. HAPAG also became a leading player in the global cargo business. In 1899 Ballin was promoted to HAPAG chief executive. By 1900 HAPAG was the world’s largest steamship line. In 1914, HAPAG had over 25,500 employees.

Diplomatic Missions and War↑

Ballin’s aggressive pursuit of HAPAG’s expansion was perceived as a threat by British government and business circles. An initial supporter of Germany’s naval expansion, Ballin changed his position in 1907/08, expressing concerns over the deteriorating German-British relations. Between 1908 and 1914 Ballin, who had access to the highest echelons of the German state, including Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941), used his longstanding contacts in London on several diplomatic missions to ease rising tensions between the two powers and reach a naval agreement, albeit without success.

The war was a disaster for HAPAG. Of HAPAG’s 175 large passenger and cargo ships, eighty were docked at German ports at the beginning of the war. Twelve liners were in enemy ports and confiscated. The other eighty-three were in neutral ports, especially in the United States. Apart from trying to find new positions for thousands of employees who were not immediately drafted, HAPAG had to maintain its mothballed fleet. Although Ballin supported some expansionist German claims, he continued to push for a fair settlement with Britain. He opposed an annexation of Belgian territory because it would not be acceptable to Britain.

Suicide?↑

On the morning of 9 November 1918, Ballin overdosed on sleeping pills. It remains uncertain whether he did so intentionally. Ballin was already pronounced dead when news of the Kaiser’s flight to the Netherlands and the declaration of the republic reached Hamburg. Leading up to his death, Ballin was a devastated man. His already feeble health had declined during the war years. As revolutionary workers and soldiers stormed HAPAG’s offices and Hamburg’s city hall, it became clear that the old order had irrevocably passed. HAPAG’s huge fleet was almost completely disbanded. It seemed unlikely HAPAG could survive the combined onslaught of German defeat, revolution and economic crisis.

Tobias Brinkmann, Pennsylvania State University

Section Editor: Christoph Jahr

Selected Bibliography

- Cecil, Lamar: Albert Ballin. Business and politics in imperial Germany, 1888-1918, Princeton 1967: Princeton University Press.

- Keeling, Drew: The business of transatlantic migration between Europe and the United States, 1900-1914, Zurich 2012: Chronos.

- Murken, Erich: Die grossen transatlantischen Linienreederei-Verbände, Pools und Interessengemeinschaften bis zum Ausbruch des Weltkrieges. Ihre Entstehung, Organisation und Wirksamheit, Jena 1922: G. Fischer.

- Rosenbaum, Eduard: Albert Ballin. A note on the style of his economic and political activities, in: The Leo Baeck Institute Yearbook 3, 1958, pp. 257-299.