Introduction↑

In this article, we will try to understand how the various artistic positionings of the time approached the war phenomenon. There are several recent studies on the period’s art history which use war depictions as references. In 1996, José-Augusto França published O Museu Militar. Pintura e Escultura. In 2018, Carlos Silveira published Adriano de Sousa Lopes. Um Pintor na Grande Guerra, which comprised the most comprehensive study on the chief protagonist of the artistic representation of the Great War, as well as on the whole artistic and political context. Osvaldo Macedo de Sousa’s Artistas Militares na Grande Guerra provides a broad account of the illustration practices among those who were fighting in the war. As regards graphic arts, one ought to highlight the essays Persuadir para vencer. O cartaz como meio de propaganda na Grande Guerra, by António Ventura, and Grafismo e design de cartazes em tempo de guerra, by Rui Afonso Santos.

This period was one of great transformation in Portuguese visual arts. On the one hand, a new understanding that challenged the established principles was proposed by modernist artists, who showed little love for post-5-October-revolution republican governments; on the other hand, the naturalist tradition found approval in both the academy and the taste of many of the young republic’s political protagonists. A year after Portugal’s official entry into the war, in March 1916, naturalist painter Adriano de Sousa Lopes (1879-1944) would be nominated to accompany the Portuguese Expeditionary Corps. He produced countless works that comprise the most comprehensive and representative body of work at the Lisbon Military Museum. Modernist artists managed to avoid deployment, despite their initial extolment of war, which was grounded in futuristic manifestoes. Christiano Cruz (1892-1951) was the exception. Deployed in 1916, over the following two years he employed an innovative modern language to produce drawings and small paintings on cardboard alluding to his experience on the front line.

Modern Art and Politics↑

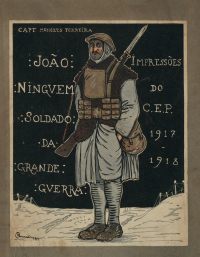

In general, Portuguese modern art manifested no objective articulation of political circumstances or projects. This was the case for 19th-century naturalism – bypassing questions as such, which were dearest to literary realism – and extended to the 20th century, until part of the third modernist generation started rethinking the matter in 1945. Even though political intervention found a more active expression in the work of some modernist protagonists, such as Almada Negreiros (1893-1970), it was grounded in literary and performative practices, and thus forwent potential productions in the field of visual arts. This generalization, however, should not disregard the practice of humorous drawing, an early modernist incitement that merged art and politics together from 1912 on. The value of the page and its distribution allowed for this articulation, while artistic practices within the fine arts system remained limited to methods of creating associated with the naturalist system, and separate from an actual problematization of the political within the artistic field. However, modernist artists, who emerged on the eve of the war and deliberately distanced themselves from the fine arts system, produced very few works in that context. It is within the sphere of caricatures and strip cartoons in wide-circulation, mechanically reproduced publications, such as magazines and newspapers, that we come across a more direct dialogue between the popular arts and historical events, although it comprises a recurrent import of French or English images. While living in Paris and writing for L’Assiette au beurre in 1915, Leal da Câmara (1876-1948) published Le barbare, the first satirical magazine aimed against the Germans, which was banned by French censorship after five issues. Upon returning to Portugal, he published Miau! in 1916, in which references to the war recur. In 1917, in Porto, he organized the group exhibition A Arte e a Guerra, although no works created from the direct experience of war featured in it. Stuart Carvalhais (1887-1961) was another, younger illustrator who paid heed to the conflict, having published illustrations of short stories and poems about the war in Ilustração Portugueza; furthermore, as the author of the comic book Quim e Manecas, he brought historical events into his stories. Army captain Menezes Ferreira (1889-1936) documented Portuguese involvement in the Great War via drawings in a language resembling that of strip cartoon. His drawings were exhibited in Lisbon in 1919, and published in the book João Ninguém. Soldado da Grande Guerra. The watercolours for his book O Fusilado are particularly interesting as regards the resemblance they bear to expressionism.

After the initial surge in humorous drawing from 1912 to 1913, with these artists taking part in it, the work of Christiano Cruz stands out due to his more elaborated, promising language. The passage from humorous drawing to the new developments in painting and a concern with the redefinition of their structural elements gave rise to new models of representation. The latter differed from naturalism or illustration, establishing, on the artistic plane, some equivalencies or analogies with certain aspects of modern life – although, as regards the Portuguese modernists that had been strongly influenced by futurism, these relationships eventually configured deliberately shocking expressions.

Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso (1887-1918), a major figure of Portuguese modernism, wrote to Robert Delaunay (1885-1941) in September 1915:

No reply survived, unfortunately; however, a month later, in a new letter addressed to Delaunay, Amadeo himself states: “I’m happy that Cendrars has survived, despite everything. It’d have been a shame if this terrible war had deprived us of such a beautiful spirit.”[2] Exchanged during the Delaunays’ stay in Portugal while fleeing the war, these letters reveal that Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso was somewhat of a flaneur amidst the Paris avantgardes, simultaneously informed by the shocking assertions of futurism and safeguarded from the global conflict back in his country of origin.

It is thus relevant to understand how the various artistic perspectives were positioned in relation to the problem of the representation of the war.

Sousa Lopes between History Painting and an Expressionism for Catastrophe↑

Sousa Lopes was the Portuguese government’s officially designated painter, accompanying the Portuguese Expeditionary Corps into the Great War. His artistic trajectory was that of a naturalist who had developed a particular sensibility to the ampleness of colour that impressionism had enabled; one which he had observed in Paris while studying but was capable of successfully carrying into history painting. According to the newspaper O Século, he would be the one “on the Portuguese front line painting the heroic and historical aspects of our military collaboration in the great war.”[3] The production of history painting seems a lively project in these assertions, and Sousa Lopes was fully motivated to do it.

Even though a genre such as history painting had seemed moribund ever since the advent of naturalism, the war suggested there were new possibilities that contrasted the dominant academic perspective. They did not come to pass. Signalling these new times, Arnaldo Garcez (1885-1964), one of the first photojournalists, became the official photographer of the Portuguese Expeditionary Corps and was integrated into the Information Division, which had been deployed in 1917 and was in charge of documenting military actions.

Art as the Language of Catastrophe↑

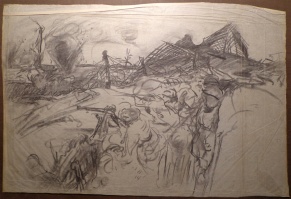

In the first moments of the 20th century, when the problem of the relation between art and history was raised, we find that art commits to a bifurcation. This bifurcation ensured the latter could not glorify “the heroic and historical aspects of [any] military collaboration in the great war,” a goal with which the participation of artists in the war was still widely associated. Sousa Lopes produced manifold artworks on the war from 1917 to 1921. His etchings are some of the most relevant works for their expressivity, dramatic distribution of masses of chiaroscuro, spatial distortions, and largely innovative forms of composition, articulated by extreme tensions between the elements of an until-then unseen, devastating landscape. The specificity of the conditions observed allowed Sousa Lopes to explore and venture down new pathways. The aestheticization of war to which such a state-commissioned project seemed committed found a profound negation in the new possibilities of artistic expression of its very construction. The circumstances of the production program that framed these artworks required an immanent perspective, and the proximity of detail dismissed any ampler spatial perspectives susceptible to the idealized distancing. Painting and drawing could survive the war as witnesses to an experience; however, in claiming the actual experience, their compositions were but able to hint at the visual distortions to which mortars, cannon shots, and mustard gas subjected the visuality of devastated fields and death. What his drawings and etchings constructed was a visual record of the war’s sheer violence and the resulting erasure of any heroic gestures. Human details and mechanical war-related elements were undifferentiatedly depicted within a convulsive landscape. Scribbled drawings became the language of catastrophe, and heroes gave way to the devastation of no-man’s-land.

History Painting↑

While these fourteen engravings constitute their own series, which is assumedly detached from the paintings produced for the Military Museum, the latter restore the original purpose of the commission in attempting to produce a new-century history painting. A rendição is particularly relevant within this series of large-scale mural paintings, for it seems to suspend the rhetoric of the heroic gesture and redirect the latter to a certain discouragement. A battalion of soldiers tread a trail where mud and snow merge into a wintry, snowy, menacingly silent landscape. The soldiers’ variably bent postures suggest a common interiority in a situation of shared silence, which highlights a supposed suspension not only in rendition but also in each one’s attempt to recover an inner space. Other than the precarious conditions of the Portuguese Expeditionary Corps operative instances, this canvas reveals the process of destruction of the very narrative to which such a painting would conform. The narrative as exchange of experience seems to suspend, if face the signs of its destruction. These soldiers embody the traumatic scene of a certain condition of modernity: the expropriation of experience. In A rendição, the grand narrative that the Military Museum set of paintings sought to produce encounters the actual capitulation of the grande manière to reveal the trauma that has silenced it within. On the other hand, other paintings made until the 1930s, titled Destruição de um obus, A volta do herói, Marcha do 15 de Infantaria no 9 de abril para La Couture, Remuniciamento da artilharia, As Mães dos Soldados Desconhecidos, and Combate do navio patrulha Augusto Castilho (unfinished due to a clash with the museum’s direction), not only disclose a dissimilar nature but also comprise the excessive dramatization of certain actions, or the loss produced by the conflict. They are simultaneously informed by a romantic remembrance and by illustrations of war episodes published in the French press, defining the heroic praise that history painting presupposes in such ways and conforming it to the banality of the illustrative sources; however, these are minor aspects within the whole of the actions depicted. Sousa Lopes’ attentiveness to living testimonies, to poems written by poet soldiers, and to his own personal experience becomes the dominant subject matter of these paintings: the sacrificial act and a display of war as barbarity. During his stay in France, he produced about 300 drawings and many medium-scale oil paintings, which are presently scattered across both countries. After these experiments on the limits of two distinct perspectives on painting, the practice of Sousa Lopes would proceed to an academized post-impressionism.

Christiano Cruz, a Modernist in the War↑

The small paintings of Christiano Cruz come from a very different perspective. A major figure of the humorist salon between 1912 and 1913, he was incorporated into the army in 1916, and deployed with the first Portuguese Expeditionary Corps in January 1917. He was the only modernist artist to have participated in the war as a soldier. As Osvaldo de Sousa stated, “he was travelling to the land of dreams, integrated into a nightmare.”[4] When he visited Paris, the centre of many of his artistic sources, he found a city that artists had deserted, a circumstance which left him profoundly disappointed. Upon his return to Portugal, as he had a doctorate degree in veterinary medicine, he followed this professional path, settling in Mozambique, definitely far off from the world of European art and its practice. Indeed, despite the temporal proximity between his late artistic production and the war, it erases a cause-effect relationship to simultaneously articulate the modernist painting’s data with a new world’s.

There is a plausible reference to the Great War in a painting from c. 1915 depicting a dead soldier; however, it is still an ambiguous one, based on a tradition from which modernism was moving away: if we look closely, the soldier presents a suit of armour in metal, showing an anachronistic situation. In 1916, at the Fantasistas exhibition in Porto, Armando de Basto (1889-1923), a modernist artist, presented a drawing about the war featuring iconographic references to the medieval period, which formed a basis to evoke a radically new present that was irrepresentable, and could only be known from second-hand accounts – despite the fact that Armando de Basto had been in Paris until 1915. The pictorial work of Christiano Cruz has been often penalized for its ambiguity in relation to the poster or the modern humoristic drawing and its stylization. However, it dismisses them in order to achieve a purer grammar in stronger consonance with the avantgardes of the time and attains a modernist quality in its own right. It might be worth considering him within these ways of making, with his forms of visibility supposing a politics of their own, capable of promoting a relation between painting and other more generalized forms of artistic production – such as the page, in his case. This is how Christiano Cruz easily articulated the data of painting with a new world, outside of naturalism.

While the aforementioned soldier seemed to allude to another period to possibly evoke the present, modernist artistic processes are more declaredly present in an untitled painting depicting Great War soldiers in a barracks. The contrast between the tone of blue and the pressed cardboard’s energetically charcoal-stroked dull browns defines the soldiers’ scene of gathering and repose. The two bodies in the foreground topple over the table in a flat symmetry that highlights the composition’s arabesque nature. There is no attempt at introspection within the painting, unlike the case of Sousa Lopes’ A rendição; however, these soldiers, as well as a third one sketched in profile, constitute the clearest expression of the shock of war and the dumbness it imposes. Their pendent, sleeping heads, inexpressive at the end of each body, have lost access to any significant identity or particularity. Such is the possibility that has been eradicated from these soldiers; only the bodies’ weariness manifests, as a sequence of a time animated by a war machine, as other paintings reveal. Cena de guerra, o rebentar de uma granada, with the extreme violence of the situation portrayed, gives a substantial account of colour, filling in saturated, flat surfaces outlined by a reticular, thick, dark line that also diagonally defines the lines of the painting’s general composition from the focus of the explosion, at the right inferior corner. The vectorial, angular shape grants the line a value of strength and generates a significant aggressiveness that falls within the general setting of the scene. The inert body thrown to the left creates a diagonal in the direction of depth without resorting to 18th-century spatial illusionism, thus allowing an emphasis on the expressionist detail of a moribund open hand against a white background. Between painting and war, there is no aestheticization of the battlefield, unlike other productions we could generically describe as futurist, for Christiano Cruz underlined the physical reality of the soldier’s body as a counter-strategy. The latter’s condition in relation to the modern technological arsenal – revealed through absence, its effects suggested – indicates the resistance of a humanity committed to a bond between modern technology and the powers which are ascribed to it. His painting is assuredly a testimony, the very body of which experiments with the chaos of martyrized bodies. In a messianic tone, Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) said that, “in last war’s nights of destruction, a sensation similar to the happiness of the epileptic shook the structure of humanity. And the revolts that followed were the first attempt to dominate its new body.”[5]

Commemorative Monuments↑

After the end of the war, the Comissão dos Padrões da Grande Guerra (Great War Monuments Commission) was created, promoting the construction of monuments or padrões in commemoration of the Portuguese involvement. Sousa Lopes, Arnaldo Garcez, and former combatants were part of the commission. Twenty-five monuments were erected all over the country, and others abroad – in particular in La Couture, in 1928, by sculptor Teixeira Lopes (1866-1942), to commemorate the Portuguese efforts at the Battle of the Lys – as well as about 100 padrões and some obelisks. Most of the monuments employed a naturalist language as regards statuary, sometimes combined with allegorical figures, within traditionalist, official patterns. Anjos Teixeira (1880-1935) was another naturalist sculptor who executed various commemorative monuments, in Viseu and Santarém. They moved away from more modern experiments, the non-commissioned production of which was indeed scarce within the panorama of Portuguese sculpture of the period. The architecture of the monuments and padrões sometimes favoured more modern, decorative elements from art deco, which was becoming established as a new style. Delfim Maya (1886-1978) executed the sculpture A caminho da posição – peça alvejada in 1938, with an expressionist grammar, thus moving away from the naturalist domain to account for the difficulties and devastation of the war.

Conclusion↑

To the artists of this period, the outbreak of war shaped very diverse perspectives, according to the artistic models and corresponding practices they followed. Although the very practice of naturalism originally opposed history painting, its academization led more traditional painters with links to naturalist models and the academy, such as Sousa Lopes, to practice that genre on the basis of unofficial commissions – with, however, generically disappointing results. The circumstance of war allowed for the extolment of nationalist values, and consequently a revival of history painting. The experience of Sousa Lopes was traumatic, as attested to by many drawings and especially the etching series, which rejects the desired exaltation. The paintings he produced employ another temporal mediation and rhetoric of making. In seeking to fulfil the expectations of both tradition and commission, they find, in their very subject matter, the living manifestation of the transformation that the world was undergoing, which precluded history painting itself. The painter’s proximity and objective attention overlapped, even somehow conflicted with the genre’s rhetoric, the emphatic gestures becoming a horizon dispossessed of its very subject.

Such dispossession is integral to the modern painting of Christiano Cruz. The relevance of structuring elements (such as the line or the chromatic plane) and the fragmentation to which the painting submits the former address a world that awakens in a dystopia of modern technology. The sentiment – or even experience, as it had been understood up until then – was expropriated; shock became the relationship with the world, as well as the latter’s with painting, which thus learned how to shape it in its most evident place of transformation. Although scarce, the drawings and paintings of Christiano Cruz are the liveliest testimony of the experiment to which he subjected modern art. To most of his modernist peers, the war was largely a sorry interruption of opportunities at an auspicious moment, when the exchange of experiences and group exhibitions across various European cities were constructing modernism as internationalism.

Pedro Lapa, Universidade de Lisboa

Section Editor: Filipe Ribeiro de Meneses

Notes

- ↑ Letter from Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso to Robert Delaunay, Manhufe-Amarante, 18 September 1915, in: Ferreira, Paulo: Correspondance de quatre artistes portugais [Correspondance of four Portuguese artists], Paris 1972, p. 75 [translated by author].

- ↑ Letter from Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso to Robert Delaunay, Manhufe-Amarante, 29 October 1915, in: ibid., pp. 76-77 [translated by author].

- ↑ Arte na guerra. Um pintor portuguez que vae para a frente portugueza [Art in the war. A Portuguese painter goes to the Portuguese front], in: O Seculo, 12 March 1917, p. 1 [translated by author].

- ↑ Macedo de Sousa, Osvaldo: O homem, o modernismo, o mito [Men, modernism, myth], in: Pereira, Paulo (ed.): Christiano Cruz Retrospectiva, Lisbon 1993, p. 18 [translated by author].

- ↑ Benjamin, Walter: Imagens de pensamento [One way street], Lisbon 2004, p. 69 [translated by author].

Selected Bibliography

- Câmara, Leal: Arte e Guerra (Art and war), Porto 1917: Société Amicale Franco-Portugaise.

- Carvalhais, Stuart: Quim e Manecas 1915-1918, Lisbon 2010: Tinta da China.

- Ferreira, Paulo: Correspondance de quatre artistes portugais (Correspondance of four Portuguese artists), Paris 1972: Presses Universitaires de France.

- França, José-Augusto: O Museu Militar. Pintura e Escultura (Military Museum. Painting and sculpture), Lisbon 1996: Comissão Nacional para as Comemorações dos Descobrimentos Portugueses.

- Garcia, Maria da Graça / Zink, João David (eds.): I Guerra Mundial. Cartazes da Coleção da Biblioteca Nacional (First World War. Posters from the National Library collection), Lisbon 2004: Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal.

- Lacaille, Frédéric (ed.): Peindre la Grande Guerre 1914-1918 (Painting the Great War 1914-1918), Paris 2000: Cahiers d’études et de recherches du musée de l’Armée.

- Leal, Joana Cunha: Trapped bugs, rotten fruits and faked collages. Amadeo Souza Cardoso's troublesome modernism, in: Konsthistorik Tideskrift 82/2, 2013, pp. 99-114.

- Leal, Joana Cunha: Uma entrada para Entrada. Amadeo, a historiografia e os territórios da pintura (An entrance to entrance. Amadeo, the historiography and the territories of painting), in: Intervalo 4, 2010, pp. 138-158.

- Matos, Lúcia Almeida: Escultura em Portugal no Século XX (1910-1969) (Sculpture in Portugal from Twentieth Century 1910-1969), Lisbon 2007: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian.

- Neto, Maria João (ed.): Sidónio Pais. O retrato do País no tempo da Grande Guerra (Portrait of the country in the Great War period), Lisbon 2018: Caleidoscópio.

- Pereira, Paulo (ed.): Christiano Cruz, 1892-1951. Retrospectiva, Lisbon 1993: Câmara Municipal Lisboa.

- Rodrigues, António: Christiano Cruz. Cenas de Guerra (Christiano Cruz. War scenes), Lisbon 1989: Quetzal Editores.

- Rollo, Maria Fernanda (ed.): Portugal e a Grande Guerra (Portugal and the Great War), Vila do Conde 2014: Verso da História.

- Rollo, Maria Fernanda (ed.): Dicionário de história da I República e do republicanismo (Dictionary of 1st Republic and republicanism history), Lisboa 2014: Assembleia da República.

- Silveira, Carlos / de Sousa Lopes, Adriano: Um pintor na Grande Guerra (A painter in the Great War), Lisbon 2018: Edições 70.

- Silveira, Maria de Aires / Silveira, Carlos (eds.): Adriano de Sousa Lopes 1879-1944. Efeitos de luz (Adriano de Sousa Lopes 1879–1944. Light effects), Lisboa 2015: Imprensa Nacional-Casa da Moeda.

- Sousa, João Silva de: Leal da Câmara. Um artista contemporâneo (Leal da Câmara. A contemporary artist), Lisboa 1984: Livros Horizonte.

- Sousa, Osvaldo Macedo de: Artistas-Militares na Grande Guerra (Military-artists in the Great War), Lisbon 2018: Tinta da China.

- Sousa, Osvaldo Macedo de: Menezes Ferreira, capitão de Artes (Menezes Ferreira, captain of the Arts), Lisbon 2014: Câmara Municipal de Lisboa.

- Vicente, António Pedro: Arnaldo Garcez um repórter fotográfico na 1ª Grande Guerra (Arnaldo Garcez a photographic reporter in World War I), Porto 2000: Ministério da Cultura.