Introduction↑

Arditi was the name given to the elite assault troops of the Royal Italian Army founded in 1917. The word “arditi” literally means daring or audacious. Their duty was to prepare the way for a broad infantry advance by attacking and infiltrating the enemy defences. They were intended for attempting to end the deadlock of trench warfare. The audacity their military role entailed helped to create a myth surrounding their endeavours. Italian wartime propaganda played its role in fashioning such a legend by circulating images of the Arditi holding grenades in their hands and daggers between their teeth while assaulting enemy lines. Moreover, the publication of a number of memoirs and accounts immediately following the end of the conflict helped to blur the distinction between history and myth about the Arditi’s wartime undertakings. The recollection of their deeds was often conflated with a hagiography of their brave and risk-taking attitudes.

Once the war was over and demobilization was under way, ex-servicemen often organized themselves into groups and associations. These groups both called for the national community to acknowledge and reward their sacrifices and claimed their right to join actively in the socio-political transformation of the country. The Arditi became involved in the peculiarly Italian experience of combattentismo (veterans' movements), a post-war phenomenon that attracted the attention of diverse political parties. Instead of subscribing to the chief veterans association, the Associazione nazionale combattenti (National Association for War Veterans), the Arditi opted to establish their own group, Associazione fra gli arditi d’Italia (Association of the Italian Arditi), in January 1919. This establishment of a separate veterans group illustrates the elitist nature of the Arditi’s experience both during and after the conflict.

Although the Associazione fra gli arditi d’Italia had ties to nationalist and right-wing groups, the arditismo movement was more diverse, as the complementary experience of the group Arditi del popolo (People’s Arditi) demonstrates.

Historiography↑

Historians differ in their views on the political outlook of the Arditi movement. While Ferdinando Cordova emphasizes their revolutionary goals, Giorgio Rochat rejects this view. He instead minimizes the political significance of the Arditi’s movement, which, monopolized by fascist sentiments soon after the war, lost its original qualities. Recent scholarship has predominantly highlighted the anti-fascist experience of the Arditi del popolo, thus emphasizing the diversity within the Arditi movement.

As Giorgio Rochat has pointed out, writing the history of the Arditi is complicated by the scarcity of trustworthy data sources and detailed documentation. Even the official records produced by military and political authorities are inconsistent when listing the number of assault units in the Italian army in 1917 and 1918. What is more, historiography has rarely tackled the Arditi’s history and experience, probably because of their glorification during the fascist dictatorship and the politicization of sections of the arditismo movement in the interwar period. In recent years, historians such as Eros Francescangeli and Marco Rossi have chiefly turned their attention to the peculiar experience of the Arditi del Popolo, a left-wing paramilitary group created to oppose the violence of fascist squads.

Beginnings↑

The Reparti d’assalto (assault units) were created in the summer of 1917 within the 2nd Army (Armata) thanks to the initiative of three officers: Lieutenant-General Luigi Capello (1859-1941), commander of the 2nd Army; Major-General Francesco Saverio Grazioli (1869-1951); and Colonel Giuseppe Bassi (1884-?), head of an infantry battalion already implementing new assault techniques. The field training imparted by Bassi in Russig (near Gorizia) had gained the approval of the High Command, which then endorsed the creation of the first assault unit. In contrast to the Austrian and German Sturmtruppen, which played a role in motivating the creation of shock troops in the Italian army, the Arditi were not regular infantry units, but rather a separate combat arm. According to some commentators, the “Explorers company” created by the Alpini lieutenant Cristoforo Baseggio (1869-1959) in 1915 were forerunners of the Arditi.

Sdricca di Manzano, near Udine, was chosen as the site where the new units would be instructed. The training programme consisted of physical exercises, hand-to-hand combat both with and without weapons, grenade handling, and assaults on entrenched positions under artillery fire. Each ardito was armed with a rifle, a dagger and many grenades, while the unit was equipped with machine and submachine guns. The shock units’ members differed from infantrymen not only in their training and weaponry, but also in the compensation they received. They received higher pay and better food, lived in nicer barracks, enjoyed a more relaxed discipline, and were granted leave more often.

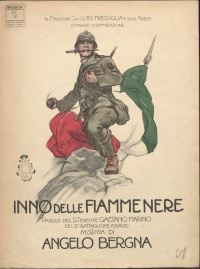

The Arditi wore black or dark green collarless jerseys under open tunics and, instead of rucksacks, had lighter and more practical equipment. In 1918 the uniform was slightly modified, as a fez and gray-green shirts with black ties were both added. The recruitment of the Arditi was of a mixed nature: many were volunteers, while others were designated by their superiors. Soldiers and officers joining these units enjoyed a unique esprit de corps, stimulated by the prestige and the special compensation they received. Their comradeship was fortified by rituals and songs (the tune Giovinezza became their hymn and was later appropriated by fascists), which in the post-war period helped to fuel the myth of the Arditi.

The Arditi’s baptism by fire occurred during the Eleventh Battle of the Isonzo (18-19 August 1917), during which they were successfully employed for the first time. After the early successes and the creation of further units, the crushing defeat encountered by Italians at Caporetto in October 1917 led to changes in the overall organization of the assault troops. Other variations of their distribution and composition within the army followed in 1918. In the final year of war, the Arditi contributed significantly to the battles fought between June and November 1918, when the armistice was signed. Nonetheless, as soon as the war was over, the High Command of the Royal Italian Army decided to dissolve the assault units.

Political Involvement↑

Although military authorities had criticized signs of politicization among the Arditi in 1918, they did not take any disciplinary action against the Associazione fra gli arditi d’Italia, established by the Arditi lieutenant (later captain) Mario Carli (1888-1935). It was most likely the Arditi’s fervent interventionism and patriotic commitment to victory that made them converge politically with other groups. In particular, the futurists and Benito Mussolini’s (1883-1945) newspaper, Il Popolo d’Italia, had cheered the Arditi’s audacity during the war and wanted them to play a role in the internal affairs of the country. It was from the pages of the periodical Roma futurista that Mario Carli urged his fellow comrades to safeguard Italy from her enemies, both external and internal. The political affinity between these groups grew stronger on two occasions: at the founding of the Fasci di combattimento on 23 March 1919 and during the assault on the editorial office of the socialist newspaper Avanti! on 15 April 1919. Fascist groups even supported the founding of the Milanese’s section of the Associazione fra gli arditi d’Italia.

In the following years, however, the partnership between the Arditi and the fascist movement was not always smooth. Some arditi had actively backed the poet and veteran Gabriele D’Annunzio (1863-1938) in his Impresa di Fiume and in the republican Italian Regency of Carnaro which followed. Mussolini, in contrast, did not enthusiastically embrace the regency. Divisions in the movement’s official line and disagreement over the identification of either D’Annunzio or Mussolini as its honorary leader brought about the dissolution of the Associazione fra gli arditi d’Italia and the creation of the Associazione nazionale fra gli Arditi d’Italia (ANAI, National Association of Italian Arditi) in 1920. This latter organization, however, also fell into disgrace. This benefited the more fascist-oriented Federazione nazionale fra gli Arditi d’Italia (National Federation of Italian Arditi), which was created in 1922 and lasted through the fascist regime. In addition to these organisations, it is worth mentioning the brief experience of the Arditi del popolo, which, promoted by some components of the Roman section of ANAI in 1921, operated as a paramilitary group fighting the fascist squads. Piloted by the ardito Argo Secondari (1895-1942), this armed group tried to oppose the violence perpetrated by the fascists against socialist, anarchist and communist militants. However, after Benito Mussolini seized power in the country, the group was disbanded.

Martina Salvante, John Cabot University

Section Editor: Marco Mondini

Selected Bibliography

- Cordova, Ferdinando: Arditi e legionari dannunziani, Padua 1969: Marsilio.

- Francescangeli, Eros: Arditi del popolo. Argo Secondari e la prima organizzazione antifascita (1917-1922), Rome 2000: Odradek.

- Rochat, Giorgio: Gli arditi della grande guerra. Origini, battaglie e miti, Gorizia 1990: Editrice Goriziana.

- Rossi, Marco: Arditi, non gendarmi! Dalle trincee alle barricate. Arditismo di guerra e arditi del popolo, 1917-1922, Pisa 2011: BFS.