Introduction↑

The extensive terminology of wartime violence against civilian populations finds expression in words such as “resettlement”, “evacuation”, “deportation”, “expulsion”, “transfer”, “exchange”, “ethnic cleansing”, and so on, to cite only those in the English language. These harsh-sounding terms scarcely begin to describe the depth of mutual antagonism and human suffering that mass warfare unleashed. It may seem an obvious point to make, but the vocabulary of discrimination and hatred was turned into concrete action by fellow human beings who responded to rapid political, social and economic changes that were already being set in motion before the First World War.[1]

Any study of resettlement must accordingly take account of human agency as well as the institutions in which key actors were embedded. We need to acknowledge expressions of ethnic and class hatred and to understand how these antagonisms were magnified by wartime mobilisation. The war supported a growing perception of one’s enemy as an aggregate, not just as contingents of able-bodied men, but as people characterised by an ineradicable difference. Nor was the enemy always to be found outside the borders of the belligerent state: internal “elements” also had to be monitored, and they too might be subject to extreme measures.

Wartime occupation was closely associated with policies to resettle civilians who were thought to pose a danger to military action or who provided the occupation regime with a convenient source of forced labour. The German occupation of Belgium, France, Poland and the Baltic lands, and the entry of the Russian army in Galicia and Bukovina in 1914-15, established the framework early on. Occupation made it both imperative and feasible to protect troops and supply lines, and to prepare for further campaigns. It also enabled the occupation regime to exploit local labour resources either for use in situ or by means of deportation to work in the national economy, as well as to appropriate other resources, such as horses and other draft animals.

Arguments about war broached questions in turn about the post-war world. In the first instance, this meant demarcating and securing borders. But wartime propaganda was inflected by the notion of a civilising mission against “barbarism”, as in German ideas of “civilising” the Baltic and Russian ideas of “liberating” Armenians from “savage” Ottoman oppression; these ideas did not evaporate in 1918. The economics of wartime occupation could readily translate from short-term considerations about the supply of food and raw materials into longer-term strategies for closer economic and commercial ties managed by the dominant partner and designed to maximise resource transfer. Resettlement formed part of these grand visions. Population management should therefore be thought of in relation to the callous contingencies of war but also in relation to plans for re-ordering the nexus between population and territory, for example by settling or “grafting” new “elements” onto territory that would (it was assumed) be retained at the end of the war. Influential adherents of such views could be found in every belligerent. This in turn meant that civil servants and military planners paid close attention to statistics and to cartography as part of the armoury of war, sifting the population into “reliable and unreliable elements” and embarking on wide-ranging programmes of resettlement.[2]

The Immediate pre-war History of Resettlement↑

Peacetime Europe witnessed widespread internal and external migration on a large scale. Of particular relevance is pre-war migration in the Russian and Ottoman empires. Millions of Russian peasants relocated to Siberia and Central Asia in more or less organised fashion, in search of better prospects. Seasonal labourers from Russia’s western borderlands worked on great estates in Germany, and were obliged to remain when war broke out. For at least a generation, Russian and East European Jews had fled persecution and sought to improve their fortunes by migrating to Western Europe and North America, an option denied them when war broke out.

In the Balkans and in the Ottoman Empire demographic “engineering” was practised long before the outbreak of the Great War. Tsarist officials did not hesitate to expel Muslim subjects of the Tsar from parts of south Russia and the Caucasus. These measures included the resettlement of Muslim refugees who fled following the war between Russia and Turkey in 1877-78 that culminated in Bulgaria’s independence. Muslims from Bulgaria, Serbia and Bosnia-Herzegovina who reached safety in Anatolia were joined by Circassians and Kurds from Russia. They were assigned land in predominantly Armenian villages. Many such refugees (muhacir) experienced downward social mobility and resented Armenians’ relative prosperity. These population movements exacerbated land disputes and religious differences and made for an unstable situation in this economically underdeveloped region.[3]

Regional instability resurfaced a generation later. The victory of the self-styled Young Turks in 1908 alarmed Vienna by appearing to revive Ottoman claims on Bosnia, where a substantial Muslim population still lived. Austria’s hasty annexation of Bosnia inflamed Serbia in turn. In 1912 Serbia, Montenegro, Bulgaria and Greece joined forces in an attempt to rid Europe of the vestiges of Ottoman administration. Ethnic Turks fled from Western Thrace when it became clear that Greece contemplated Hellenisation. The violence inflicted on Muslim landlords and merchants in Macedonia by partisans caused a sudden influx of 180,000 refugees to Constantinople and other towns and cities during the first half of 1913. Greek merchants were attacked in turn.

When the anti-Ottoman coalition broke apart, Greece and Serbia sided with Turkey against Bulgaria. Tens of thousands of ethnic Bulgarian refugees fled from their homes in Thrace, Macedonia, Dobrudja and Anatolia to the relative safety of Bulgaria. The Second Balkan War concluded with substantial territorial gains in Macedonia for both Serbia and Greece. Furthermore, Bulgaria and Turkey agreed to the “voluntary and reciprocal” transfer of around 47,000 Christians from the borders of Eastern Thrace to Bulgaria and 49,000 Muslims from Western Thrace to Turkey. Turkey sanctioned a similar exchange of population with Greece and Serbia. Although the outbreak of war prevented the full implementation of these agreements, some orchestrated expulsions did take place, for example in western Anatolia where Greeks were required to make way for Muslim refugees. Population displacement prior to and during the Balkan Wars thus carried echoes of previous conflicts whilst also prefiguring later upheavals.[4]

Occupation and Flight from the Enemy↑

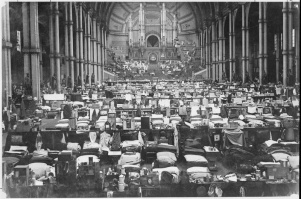

In the first months of the war, German and Austrian civilian populations fled from advancing Russian troops. When the tables were turned later in 1914 and in 1915, their counterparts in Russia followed suit, including tsarist officials who abandoned their posts in Poland. Civilians in Habsburg-ruled Galicia likewise sought to flee the Russian onslaught, often doubling or trebling the population of small towns in Hungary. The rapid Russian advance into Galicia and Bukovina provided the opportunity for ultra-nationalists to “liberate” or “reclaim” fellow Slav populations from Habsburg oppression. Galician Jews escaped for the relative safety of Vienna and other towns and cities.[5] At the outbreak of war, Greek, Armenian and Russian colonists fled their farms on the Kars plateau for the relative safety of Erevan or Tiflis, returning when the Turkish army withdrew.[6] Conflict between Habsburg troops and Italians produced the same result. In Western Europe, the occupation of Belgium and northern France prompted an exodus of civilians. Numbers grew rapidly in successive days and weeks, fuelled by rumours that the German army intended to forcibly conscript all men between the ages of twenty-eight and fifty. These fears were not unfounded. By the end of the year, around 1.5 million Belgians had become refugees.[7]

French civilians also left their homes to escape enemy bombardment, but many ordinary people also fled in fear that they might suffer atrocities at the hands of German troops who convinced themselves that franc-tireurs were concealed among the civilian population. On 15 September 1914 the French Minister of War Alexandre Millerand (1859-1943) banned the publication of such stories on the grounds that they “terrified the population and ran the risk of provoking the most deplorable exodus”. Within the zone of military operations the authorities tried to control the movement of civilians: residents of Longwy, Verdun, Epinal and Belfort who lived close to the front were evacuated as “useless mouths to feed”. They were followed soon afterwards by inhabitants of the departments to the north and east.[8]

The invasion of East Prussia by the Russian army in August 1914 caused the abrupt flight of at least 500,000 and perhaps as many as 800,000 civilians to Germany, sometimes in convoys, but more often in a less organised fashion. The second Russian advance, in October 1914, led the German high command to organise another evacuation, involving 350,000 civilians. Tsarist troops were finally dislodged in February 1915. Although reports of Russian atrocities in the first weeks of war were probably exaggerated, there was an element of truth in the rumours that circulated of Cossack brutality, particularly during the hasty Russian retreat in 1915, following which some refugees returned to their homes.[9]

The reverses suffered by the tsarist army in spring 1915 had a pronounced impact on the civilian population. In the western borderlands, people left their homes out of fear of being terrorised by enemy troops. Nor were these alarms misplaced: “rumours are rife that the Germans have behaved abominably towards the local population”. Another report concluded that, “on the borders of our Russian homeland is a ruthless scourge; the blood is flowing in Poland, Galicia, Lithuania, the Caucasus. The enemy does not spare the land it has seized; whatever cannot be taken is destroyed. The population flees in a great horde from wretched native towns and villages”. However, an additional factor was the behaviour of the Russian army. Within the extensive theatre of military operations the Russian high command was accused of pursuing a scorched earth policy and driving civilians from their homes. Sometimes civilians were conscripted in order to deny the enemy the use of their labour. “We didn’t want to move, we were chased away. We were forced to burn our homes and crops, we weren’t allowed to take our cattle with us, we weren’t even allowed to return to our homes to get some money”, in the words of one group of refugees.[10]

The costly military engagement between Italy and Austria-Hungary following Italy’s decision to enter the war in April 1915 was marked by the pre-emptive flight of ethnic Italians from Trento, Trieste, Istria and Dalmatia, who feared internment by the Austrian authorities. Italy called them “returnees” (rimpatriati, literally, “repatriates”). Those who remained behind were quickly evacuated from the front line by Italian commanders in the Trentino and in the east. Following the disastrous defeat of the Italian army at Caporetto in 1917, which led to the retreat of 1 million Italian soldiers, around 500,000 civilian refugees fled from Friuli and the Veneto. In Italy they encountered a fragile and divided society.[11]

Among other campaigns that resulted in the mass evacuation of civilians was the Brusilov Offensive in 1916, as a result of which many of the remaining German colonists fled Volynia in 1916 for the relative safety of the Reich.[12] Elsewhere, too, military engagements had similar outcomes, such as in Verdun where the offensive in early 1916 led to the evacuation of 45,000 civilians in a matter of weeks. The population of Rheims also dwindled rapidly. The German offensive in the spring of 1918 launched another mass exodus of around 200,000 people between March and August.[13]

Deportations and Organised Labour drafts on Enemy-Occupied Territory↑

The armies of the great continental empires enjoyed considerable latitude as they swarmed across enemy territory. Inevitably, their priority was the security of military personnel and assets, and how best to exploit local labour to gain an advantage over the enemy. In occupied East Galicia, an added factor was the anti-Semitism of Russian commanders and rank-and-file soldiers, who singled out Jews as dangerous “elements”. Military leaders and their subordinates thus tended to dictate policy, leaving politicians as bystanders. However, political strategy also preoccupied government officials, who looked upon ethnic minorities as potential instruments to undermine rival states and who envisaged economic reform as a means of gaining popular support, as in Galicia where the Central Powers and the tsarist state alike had Polish landlords in their sights. This was a complicated game to play.

In East Prussia the Russian occupation forces identified potential subversives at the outset. At least 15,000 German government officials and other civilians, men, women and children were deported (verschleppt) in the first phase of the war, either on the grounds that they were spies or to prevent them from serving in enemy uniform. After a lengthy ordeal in overcrowded goods wagons they ended up in the Volga region, in Central Asia or in Siberia, where the huge military camp in Krasnoiarsk housed 15,000 of these “prisoners” by 1916. It was a death-trap. Only in 1918 did survivors make their way home.[14]

In Galicia and Bukovina, the commander-in-chief Nikolai Nikolaevich, Grand Duke of Russia (1856-1929) and General Nikolai Ianushkevich (1868-1918), and the newly-installed governor Count Georgii Bobrinskii (1868-1928), claimed that they had restored these “Russian lands” to tsarist rule. Beginning in January 1915, entire Jewish communities were rounded up, ostensibly to “protect” the non-Jewish population from the consequences of collaborationist intrigue. By 1916 as many as 30,000 East Galician Jews were deported to the Russian interior, in addition to some 50,000 who were forcibly displaced in the region. Polish and Ukrainian ultra-nationalists were systematically taken hostage and deported from Galicia and Bukovina. Several dozen Ukrainian church leaders and other local notables were in time despatched to Siberia. One contemporary estimated that 120,000 civilians were deported by the occupation regime. Many ended up beyond the Urals. Taking his cue from provincial governors, who disposed of sweeping powers to remove individuals who threatened state security, Bobrinskii endorsed a policy of “purifying unreliable elements”, although he did not go far enough for the likes of Ianushkevich. Recent scholarship suggests that by confiscating Polish and Jewish property in Galicia the army hoped to curry favour with the local “Ruthenian” peasantry. Further attacks on Galician Jews followed the Brusilov offensive in 1916, although the harsh measures taken in 1914-15 were no longer so widespread.[15]

Occupation regimes made equally concerted efforts to compel civilians to work on their behalf in order to replace military conscripts and to supplement the domestic labour force. These compulsory labour drafts did not necessarily mean service in the factories and fields on enemy territory. In occupied Lithuania, for example, the German military regime (Land Ober Ost) decreed in mid-1916 that all men and women on occupied territory, whatever their age or state of health, were liable to work for the military administration. As a result, civilian labour battalions (Zivile Arbeiter Bataillone) deployed workers to help with the local grain harvest, collect timber, and on road building projects. Conditions were arduous. Arnold Zweig (1887-1968) described the regime as “a kind of Siberia”, but a German official simply retorted that “the Lithuanian is by nature given to whining”. Around 130,000 civilians in Lithuania were forced into these gangs, excluding those who were deported to Germany. The result was an increase in armed resistance by Lithuanian partisans, including men who deserted from the labour battalions. Their campaign only came to an end with Germany’s defeat.[16]

Part of the overall objective was to promote German settlement in the Baltic lands, something that reached its apogee in 1916-17 under the autocratic rule of Erich Ludendorff (1865-1937). Assessments of rural property-holding and of the characteristics of local farmers formed an important element of his overall project. In pursuit of a German “human wall”, Ludendorff and his staff pondered the expulsion of Lithuanian farmers and their replacement with German “fighting farmers” who would secure the territory “with sword and plough” and boost agricultural productivity.[17]

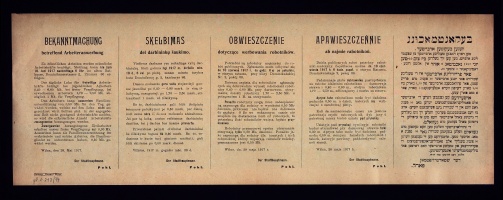

The deportation of foreign labour to be exploited for the benefit of the domestic war economy was particularly marked in Russian Poland, where the new German civilian administration recruited Polish workers, including Jewish tradesmen and artisans who had lost their jobs when the local economy collapsed in 1914. Later on they were sent to the Land Ober Ost to supplement the Lithuanian workforce. This pattern was repeated elsewhere. Germany put at least 120,000 Belgian civilians to work in the war economy, either by deporting them to Germany or compelling them to work in occupied France and Belgium in the same manner as deported Poles. In Lille, the German authorities deported 20,000 Belgian women and girls to Germany in humiliating circumstances; Belgians were still being deported in the last weeks of the war.[18]

Serbia constituted another crucible of displacement. The invading Habsburg army targeted Serbian guerrillas in order to forestall what they most feared, a levée en masse or uprising of the entire population. Thousands of Serbs were interned as a preventive measure, but a tug-of-war then ensued between the occupation regime, on the one hand, and the administration in Vienna whose officials cried out for extra labourers.[19] Bulgaria’s occupation of Macedonia following its entry into the war in September 1915 was accompanied by the mobilisation of adult males on occupied territory for the Bulgarian war effort, as well as the deportation of thousands of Serbs, Greeks and others, particularly from the professional elite, to Sofia and other destinations. Property belonging to Greek refugees was seized.[20] In May 1915 Italian troops occupied the territory of western Slovenia and proceeded to deport around 10,000 Slovenian and Croatian civilians from Posocje and Istria to destinations in the Italian interior. Likewise, Austria transferred ethnic Italians from the Trentino and the Julian Marches to internment camps such as Wagna in Styria, which by the end of 1915 accommodated more than 20,000 people. However, not all occupation regimes engaged in concerted deportation of this kind. In Romania, for example, the German military administration acknowledged that deportation was not worth the trouble, particularly when the local population accepted, albeit reluctantly, the need to supply grain and raw materials to the Central Powers after 1916.[21]

“Population Politics” – Deportations of the “Enemy Within”↑

The absence of significant restraint on the freedom of military manoeuvre had pernicious consequences for the conduct of internal politics during the First World War. “Enemy aliens” were rounded up and sent to internment camps. In addition, the doctrine of military security created an unstoppable momentum in multinational empires where ethnic minorities were deemed potentially subversive, particularly where members of the same ethnic group lived in a contiguous opposing state. This directly affected German subjects of the Tsar, Armenians who lived under Ottoman and Russian rule, Ukrainians and Poles who were distributed between the Russian and Habsburg empires, and Jews throughout Central and Eastern Europe.

Russian generals disposed of sweeping powers to enforce the resettlement of civilians where they deemed appropriate. Wartime regulations permitted the military authorities to assume absolute control over all affairs in the theatre of operations. The army had jurisdiction over Poland, Finland and the Baltic provinces. As the Russian army retreated, its rule extended to other parts of European Russia. This jealously guarded licence provided one of the main impulses behind population displacement. From the outset, the General Staff recommended that enemy aliens be interned and deported, in order to prevent them from enlisting in the opposing army. Russian commanders advocated “deportation without exemption” (pogolovnoe vyselenie) and described the result – the expulsion or deportation of around 300,000 civilian foreign citizens during the war – as “cleansing” (ochishchenie). These measures were extended to Bulgarian subjects following Bulgaria’s declaration of war on Russia in October 1915.[22]

German colonists in Russian Poland and in the southwest of Russia became the target of military wrath, notwithstanding their lengthy residence in Russia and protestations of loyalty. In August 1914 the Russian high command and the Ministry of the Interior drew up plans for their deportation. As a government official put it: “the colonists...live so detached an existence from the native Russian population that, all in all, they constitute a ready base for a German attack through our southern provinces”. Backed by a vitriolic press campaign, including suggestions for deporting them to uninhabited parts of the far north, around 420,000 men, women and children were unceremoniously deported from the Polish provinces in December 1914. Ianushkevich denounced them as fifth-columnists. Nor did the assault on persons and property come to an end in 1914. The great retreat in summer 1915 was accompanied by another wave of expulsions from the western and south-western provinces of Volynia, Bessarabia, Tauride, Ekaterinoslav and Kherson, with further mopping-up operations in 1916 to complete a systematic programme of deportation. General Aleksei Brusilov (1853-1926) forced a further 13,000 settlers out of Volynia during the June 1916 offensive, and ordered them to move to Penza, Riazan’ and Tambov. Those who protested that they were loyal subjects were rebuffed by the claim that they were being deported for their own protection. Refugees from Galicia were expected to take over their farms.[23] Military, economic and political imperatives thus provided contemporaries with a rationale for harsh measures.

The Russian army targeted other vulnerable minorities in an attempt to find scapegoats for military failure. Russian gypsies and Crimean Tatars did not escape unscathed, and Muslims in Kars and Batumi provinces were forced to hand over their farms to Armenian refugees in 1915. Jews suffered acutely. Russian generals confidently asserted that “the complete hostility of the entire Jewish population towards the Russian army is well established”. Russian troops, including Cossack soldiers far from home who encountered Polish Jews for the first time, mistook Yiddish for German, and this ignorance only reinforced the message from their superiors that Jews were not to be trusted. Expressions of patriotism by Jewish politicians were to no avail. The war provided their neighbours with an opportunity to denounce Jews for reasons of personal animosity and in the hope of some reward for turning “spies” over to the authorities. Such distorted preconceptions underpinned widespread attacks on Jews and Jewish property. As early as September 1914, a local army commander expelled the entire Jewish population from the small Polish fortress town of Novo-Aleksandriia (Pulawy), giving them just twenty-four hours’ notice. This was not an isolated instance. Using the likelihood of espionage as a pretext General Nikolai Ruzskii (1854-1918), commander of the northern front, ordered the entire Jewish population to leave Plotsk Province in January 1915. What began as sporadic and unsystematic actions in 1914 turned into methodical deportations in the spring of 1915, accompanied by mass looting. One estimate puts the total number of Russian Jews who were displaced at more than 600,000. When the Russian army targeted Jewish residents in the western borderlands, some politicians voiced their opposition, but to little effect.[24]

The intensification of antagonism reached its apogee in the Ottoman Empire. In 1913 officials established a new Directorate for the Settlement of Tribes and Immigrants, charged with finding refugees somewhere to live and conducting ethnographic investigations of Ottoman society to map political affiliations and discover the extent of “Turkishness”. One prominent victim of this pre-war downward social mobility, Mehmet Talat Pasha (1874-1921), posed the rhetorical question:

Government officials adopted a “five-ten percent” formula, whereby resettlement was expected to produce a maximum of one-tenth non-Turkish population in Anatolia and in the regions to which Armenians were deported.

A key issue in Ottoman demographic policy was the perceived threat to national security that arose following the Armenian Reform Act (the Yeniköy Accord) of 8 February 1914, whereby Britain, France, Germany and Russia compelled Turkey to agree to the division of Eastern Anatolia into two provinces with authority vested in a foreign inspectorate. This was the first step (as the Russian international lawyer Andrei Mandel’shtam (1869-1949) put it) “towards rescuing Armenia from Turkish oppression”, although official tsarist policy was far more cautious.[26] The Committee of Union and Progress regarded the agreement as a betrayal by Armenian leaders and as a fundamental threat to Ottoman territorial integrity and national security, and tore up the accord when Turkey entered the war in November 1914. War stoked fears of an insurgency by Armenian irregular forces in Eastern Anatolia and led to the close monitoring of local Armenian political leaders in order to deter “provocations”. The Russian military advance in 1915 revived Turkish fears of a breakaway Armenian state and of Russian colonisation. Instructions were issued to deport “bandits” and “deserters”, and to prevent Armenian men, women and children from leaving the country. In the menacing words of Talat Pasha, speaking to a German journalist, “those who were innocent today might be guilty tomorrow”.[27]

The stakes grew much higher in the following months. The Battle of Sarıkamış in January 1915 turned into disaster for the Ottoman army. It was followed by the struggle over the Dardanelles at Çanakkale (Gallipoli) and fears of the imminent loss of Constantinople itself. Tight restrictions were placed on the movement of Armenians of all ages. Uprisings in Van in the months of April and May led the state to issue a decree that provided for deportation where “security and military interests” demanded it. Secret instructions were delivered by special courier in May 1915 for the “total deportation” of Armenians from Zeytun, Erzerum, Bitlis and Van to the area around Damascus and Aleppo. In a coded telegram dated 29 August 1915, Talat Pasha wrote to provincial governors that:

The language reflected the animosity felt towards Armenians, who were described as “internal tumours” and “vermin”. It also reflected a precise statistical delineation of the numbers deported, the quality and quantity of the land they forfeited, the food and draft animals that could be handed over to the Turkish army, and the vacant property that could be assigned to Muslim newcomers, including refugees who had fled the fighting in the Caucasus. Muslim refugees were also settled on coastal properties that Greek villagers were forced to abandon in 1916-1917.[29]

Much of this became known to audiences in the USA and elsewhere thanks to organisations such as the National American Committee for Armenian and Syrian Relief and the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, in both of which James L. Barton (1855-1936) occupied a key role by encouraging all American missionaries from the Ottoman Empire who returned to the USA to complete a questionnaire in 1917 for submission to a US Presidential commission on aspects of the war. Missionaries disseminated bulletins and leaflets with titles such as The March of the Martyrs.[30] William Walker Rockwell (1874-1958), a Congregationalist minister and librarian of Union Theological Seminary between 1905 and 1942, was particularly active in promoting awareness of the crisis among the American public. He distinguished between a “zone of war” (resistance at Van and Zeitoun) and a “zone of panic” (affecting civilians in Harpoot and elsewhere). He described deportation by rail as “systematically planned and controlled by telegraph … undoubtedly with foreign expert advice”, whereas deportation on foot was left to local military commanders.[31] In his view deportation “should have been humanely carried out, with regards if not to feelings then at least to the rights of property, food [and] clothing”, adding that “the exiles would of course feel the wrench of abandoning the homes they would never see again. But might not a benevolent deportation provide other homes in a distant locality, where the exiles would learn to love, where they would become contented citizens?” In Diyarbekir, Erzerum and Trebizond, however, “expatriation usually meant extermination”.[32]

The total number of deported Armenians has been put at around 1.2 million. Following deaths from hunger and infectious disease en route from Anatolia, as well as massacres in temporary camps, only 300,000 Armenians were left alive in the Syrian provinces of the Ottoman Empire by the beginning of 1916, out of a total of 850,000 deportees. No significant local restraints were placed on Ottoman action. Although the German missionary Johannes Lepsius (1858-1926) denounced the deportations and massacres, as did the new German ambassador Paul Wolff-Metternich (1853-1934), their voices were drowned out in the general clamour for targeted action towards these “internal enemies”.[33]

The contrast with Russian policy towards Muslims in the Caucasus is striking. Although tsarist troops did not hesitate to punish local Muslim villagers, they stopped short of expelling them, despite recommendations from some local officials that Muslim civilians be deported to the Russian interior or sent to the Ottoman Empire at the end of the war. Russian provincial governors protested that they could not accommodate Muslim deportees, and the army opposed such action for fear of spreading infectious disease. Here, at least, military considerations acted as an obstacle rather than a spur to deportation. Meanwhile the Tsar’s closest advisers concluded that the case against his Muslim subjects in the Caucasus did not stack up.[34]

Elsewhere, the German encounter with the Baltic lands and with Poland helped to support a programme for the organised settlement of Germans throughout the region. This formed part of a “civilising” process, whereby “inferior” and “backward” Poles, Latvians and Lithuanians would be supplanted. Local resistance only served to encourage more purposeful and brutal actions on the part of the occupation regime whose spokesmen reminded critics of the brutal temporary Russian administration in East Prussia in the autumn of 1914. The so-called civilising mission was given a further lease of life following the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk in March 1918, when ethnic Germans were expected to leave Bolshevik Russian territory and settle in the Baltic as part of an enlarged German state. Austrian military leaders evacuated tens of thousands of Slovenians from the Isonzo (Soca) valley in the course of the war, and despatched around 100,000 ethnic Italians – subjects of the Habsburg Empire – to internment camps in Austria, Bohemia and Moravia.

Revolt, and Punitive Resettlement or Flight↑

No discussion of wartime evacuations would be complete without mentioning the drastic consequences for participants who took up arms against the state. The main instance is the 1916 revolt in Central Asia, where the actions of the tsarist state fell into a pattern familiar from the great revolts against Romanov rule in Poland in 1863 and in some parts of the Russian periphery in 1905 – namely the execution or internal banishment of ringleaders and their sympathisers.

The tsarist government attributed partial responsibility for the revolt in Central Asia to external intervention by Germans and Turks, but officials also took the view that Kazakhs could not, by virtue of their ethnicity, be trusted to be loyal members of the imperial polity. Repression was merciless. The regime deployed Cossack punishment squads as well as regular army troops who resented the fact that they were expected to fight the rebels rather than Germans or Austrians. When the protracted siege of Turgai was lifted in November 1916, its Kazakh inhabitants were unceremoniously deported, in terrible weather and without adequate clothing. Those who evaded capture crossed over into China, preferring exile to the risk of execution: estimates of this pre-emptive flight range from 250,000 to half a million. Many died en route. By the end of 1916 the revolt had subsided, although pockets of resistance continued well into 1917. The situation in the region changed in important respects following the February Revolution. At the end of March 1917 the Provisional Government proclaimed an amnesty for those who had taken part in the revolt. Land that had been seized after the revolt was returned to its original owners. Nonetheless, martial law continued in many districts and the government procrastinated over the issue of land that had been granted to Russian settlers prior to the war. Throughout the Civil War period and beyond the Basmachi (“bandits”) in the Fergana valley maintained a kind of guerrilla warfare against Soviet rule, protesting the requisitioning of food and – in an eerie echo of 1916 – the forced conscription of Muslim troops into the Red Army.[35] Here, then, was another example of the wartime link between mobilisation and population politics.

Aftermaths: Resettlement as Peace-making↑

Given the extensive wartime practice of deportation, the question arises as to whether military and civil authorities expected to reverse the process when the war came to an end. In the case of the Greek and Armenian population of the Ottoman Empire, the Committee of Union and Progress envisaged deportation as irreversible. The ambitions inherent in resettlement reached their apogee in Lithuania, where Poles, Lithuanians and Latvians were expected to give way to German settlers.[36] It is less clear whether tsarist authorities felt the same about the deportation of Germans, Jews and others in 1914-15, but there was a tendency to characterise them as “unassimilated” and by extension “unassimilable”. Of course, the October Revolution represented a dramatic change of course. In the short term, the Russian Civil War unleashed a fresh round of evacuations and deportations – the deportation of Terek Cossacks being a case in point – along with the creation of a revolutionary society according to Bolshevik blueprints.

As we saw earlier, organised population exchanges had been agreed upon before the outbreak of the First World War. Decisions to arrange for the transfer of population were implemented in Turkey and Greece under the terms of the Lausanne Peace Treaty in 1923. Arguments about the desirability of population exchanges continued long after the First World War, and are still being aired in some circles a century on. What the advocates of population exchange invariably discount is the abundant evidence of continued antagonism that the policy was designed to mitigate. Years after Lausanne, ethnic tensions persisted, as is evident from the demeaning characteristics that were attributed to Greeks from Anatolia who settled in Macedonia after 1923, and who were described as having been “baptised in yoghurt”. Thus “unmixing”, far from creating a more harmonious society, instead provoked further antagonism.[37] Elsewhere, too, the legacy of the First World War had unsettling implications. In Germany, for example, the assassination of Talat Pasha led to demands for the expulsion of all Armenians from German territory.[38]

Conclusion↑

The conduct of warfare directly entailed population resettlement, whether as a result of pre-emptive decisions to flee or of tactics pursued by military leaders and their political masters, who targeted people on occupied territory as well as homegrown minorities on grounds of national security. In Russia, critics of the army’s behaviour reckoned that only one in five displaced civilians had chosen to leave their homes in 1915; the rest were forced migrants. Tsarist deportations of Germans, Jews, Poles, Latvians and others were legitimised in terms of the risks posed by spies, deserters and opponents of tsarist rule. Spasmodic deportation soon gave way to more systematic resettlement. Brutal as these measures were, they did not culminate in extermination. Jews even experienced a kind of liberation as the infamous Pale of Settlement disintegrated and they were allowed to settle deep in the Russian interior. Nor did the tsarist state behave in a uniformly vicious fashion, even if individual military commanders were guilty of acting brutally towards those whom they deemed to be harmful.

If in the Russian Empire there was a degree of haphazardness about state policy, at least to begin with, deportations in the Ottoman Empire were far more calculated, as is suggested by the statistical precision with which officials loyal to the Committee for Union and Progress determined the maximum number of Armenians who were eligible for internal resettlement. In Russia organised deportation was not associated with the reorganisation of property relations, with the exception of measures taken against the German minority and some Muslim farms in the Kars and Batumi provinces. In the Ottoman Empire, on the other hand, the confiscation of property was part of an orchestrated campaign against the entire Armenian population that began with the use of demeaning linguistic terminology and ended with mass murder. Russian policy was determined primarily by arguments around military necessity, whereas Ottoman policy was driven by ideological certainty.

The notion of a “civilising mission” was embodied in the policies of the Land Ober Ost to “clean” the “unhygienic” native population of Lithuania. In the longer term, the doctrine of economic development took over from notions of “civilisation”, although as we have seen economic imperatives were also present during the war. Warfare provided opportunities to recast the relationship between population and territory, to reward key social groups in the short term and to embark on agricultural modernisation in the long term. Memories of wartime occupation and deportation contributed to a sense of “unfinished business”.

A generation after the end of the Great War, countries in Eastern, East Central and South East Europe witnessed a further concentrated round of resettlement. How far the policies instituted during the First World War served as a “blueprint” for brutal forced labour and cataclysmic deportation in the Second World War remains a question for further research.[39] To be sure, the Holocaust surpassed in aims and outcomes anything witnessed hitherto. But any suggestion that Nazi and Stalinist programmes of population resettlement marked a clear break with past practice is bound to be overstated in the light of what we know about the projects embraced by belligerent powers during the First World War.

Peter Gatrell, University of Manchester[40]

Section Editor: Holger Afflerbach

Notes

- ↑ Mann, Michael: The Dark Side of Democracy. Explaining Ethnic Cleansing, Cambridge 2005; Naimark, Norman: Fires of Hatred. Ethnic Cleansing in Twentieth-Century Europe, Cambridge 2001; Bloxham, Donald: The Great Unweaving. Forced Population Movement in Europe, 1875-1949, in Bessel, Richard / Haake, Claudia (eds.): Removing Peoples. Forced Removal in the Modern World, Oxford 2009, pp. 167-208.

- ↑ Holquist, Peter: To Count, to Extract and to Exterminate. Population Statistics and Population Politics in Late Imperial and Soviet Russia, in: Suny, Ronald G. / Martin, Terry (eds.): A State of Nations. Empire and Nation-Making in the Age of Lenin and Stalin, New York 2001, pp. 111-44.

- ↑ Mann, Dark Side of Democracy 2005, pp. 111-31.

- ↑ Akçam, Taner: The Young Turks' Crime Against Humanity. The Armenian Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing in the Ottoman Empire, Princeton 2012, p. 69; Adanır, Fikret: Non-Muslims in the Ottoman Army and the Ottoman Defeat in the Balkan War of 1912-13, in: Suny, Ronald Grigor/Göçek, Fatma Müge / Naimark, Norman (eds.): A Question of Genocide, 1915. Armenians and Turks at the End of the Ottoman Empire, New York 2011, pp. 113-25.

- ↑ von Hagen, Mark: War in a European Borderland. Occupations and Occupation Plans in Galicia and Ukraine, 1914-1918, Seattle 2007, pp. 20-1.

- ↑ Price, Morgan Philips: War and Revolution in Asiatic Russia, London 1918, pp. 184-5.

- ↑ Gatrell, Peter: Refugees, in 1914-1918 online.

- ↑ Horne, John / Kramer, Alan: German Atrocities. A History of Denial, New Haven 2001, pp. 175-86, quotation on p. 184; Nivet, Philippe: Les réfugiés français de la Grande Guerre, ‘les Boches du Nord’, Paris 2004, pp. 71-2.

- ↑ Gause, Fritz: Die Russen in Ostpreussen, Königsberg 1931, pp. 40-79; Horne / Kramer: German Atrocities 2001, p. 79; Liulevičius, Vėjas Gabriel: War Land on the Eastern Front. Culture, National Identity, and German Occupation in World War I, Cambridge 2001, pp. 38-9; Liulevičius, Vėjas Gabriel: Precursors and Precedents. Forced Migration in Northeastern Europe during the First World War, in: Nordost-Archiv 14 (2005), pp. 32-52.

- ↑ Gatrell, Peter: A Whole Empire Walking. Refugees in Russia during World War I, Bloomington 1999, pp. 15-16; Sanborn, Joshua A.: Military Occupation and Social Unrest. Daily Life in Russian Poland at the Start of World War I, in Alexopoulos, Golfo/Hessler, Julie/Tomoff, Kiril (eds.): Writing the Stalin Era. Sheila Fitzpatrick and Soviet Historiography, New York 2011, pp. 33-58.

- ↑ Gatrell Peter/Nivet, Philippe: Refugees, in: Winter, Jay (ed.): Cambridge History of the Great War, Volume 3, Chapter 8, Cambridge 2014.

- ↑ Sammartino, Annemarie H.: The Impossible Border. Germany and the East, 1914-1922, Ithaca 2010, p. 35.

- ↑ Gatrell / Nivet: Refugees 2014.

- ↑ Gause, Die Russen 1931, pp. 236-82 (figures on p. 246); Liulevicius, War Land 2001, p. 40; Tiepolato, Serena: La deportazione di civili prussiani in Russia, 1914-1920, in: Bianchi, Bruna (ed.): La violenza contro la popolazione civile nella Grande guerra. Deportati, profughi, internati, Milan 2006, pp. 107-25; Tooley, T. Hunt: World War I and the Emergence of Ethnic Cleansing in Europe, in: Várdy, Steven B./Tooley, T. Hunt (eds.): Ethnic Cleansing in Twentieth-Century Europe, Boulder 2013, pp. 63-97. The compendium by Fritz Gause (1893-1973) contains an extensive bibliography of works in German and Russian.

- ↑ “Ruthenian” was the term used to describe the Ukrainian-speaking population of Galicia and Bukovina who were regarded as kin of Ukrainians who lived under Tsarist rule. See Prusin, Alexander: Nationalizing a Borderland. War, Ethnicity, and Anti-Jewish Violence in East Galicia, 1914-1920, Tuscaloosa 2005, xii, pp. 48-62; von Hagen, War in a European Borderland 2007, pp. 32-34, 74; Holquist, Peter: The Role of Personality in the First (1914-1915) Russian Occupation of Galicia and Bukovina, in: Dekel-Chen, Jonathan (ed.): Anti-Jewish Violence. Rethinking the Pogrom in European History, Bloomington 2010, pp. 52-73; Bakhturina, A. Iu.: Politika rossiiskoi imperii v Vostochnoi Galitsii v gody pervoi mirovoi voiny [The Politics of the Russian Empire in East Galicia during the First World War], Moscow 2000, pp. 194-5; Lohr, Eric: Nationalising the Russian Empire. The Campaign Against Enemy Aliens during World War I, Cambridge 2003, p. 215, fn. 25.

- ↑ Quoted in Liulevicius, War Land 2001, p. 74; Westerhoff, Christian: ‘A Kind of Siberia’. German Labour and Occupation Policies in Poland and Lithuania During the First World War, in: First World War Studies, 4/1 (2013), pp. 51-63.

- ↑ Liulevicius, War Land 2001, pp. 95-6; von Hagen, War in a European Borderland 2007, p. 61.

- ↑ De Schaepdrijver, Sophie: La Belgique et la première guerre mondiale, Berlin/New York 2004, pp. 221-30.

- ↑ Gumz, Jonathan E.: The Resurrection and Collapse of Empire in Habsburg Serbia, 1914-1918, Cambridge 2009, pp. 89-104, 193-5.

- ↑ Opfer, Björn: Im Schatten des Krieges. Besatzung oder Anschluss - Befreiung oder Unterdrückung? Eine komparative Untersuchung über die bulgarische Herrschaft in Vardar-Makedonien 1915-1918 und 1941-1944, Münster 2005, pp. 75-6, 116-7, 120. The territory of Vardar Macedonia had been assigned to Serbia by the Treaty of Bucharest (1913) that ended the Second Balkan War.

- ↑ Mayerhofer, Lisa: Making Friends and Foes. Occupiers and Occupied in First World War Romania, 1916-1918, in: Jones, Heather/O’Brien, Jennifer (eds.): Untold War. New Perspectives in First World War Studies, Leiden 2008, pp. 119-50.

- ↑ Lohr, Nationalising the Russian Empire 2003, p. 123, pp. 126-7, 162-3; Nelipovich, S. G.: General ot infanterii N. N. Ianushkevich. ‘Nemetskuiu pakost’ uvolit’ i bez nezhnostei. deportatsii v Rossii 1914-1918 gg. [Infantry General N.N. Ianushkevich: German filth must be cleared out without showing tenderness: deportations in Russia, 1914-1918], in: Voenno-istoricheskii zhurnal [The Journal of Military History (in Russian)], 1 (1997), pp. 42-53; von Hagen, War in a European Borderland 2007, p. 29.

- ↑ Lohr, Nationalising the Russian Empire 2003, pp. 130-37, 149; Nelipovich, S. G.: V poiskakh ‘vnutrennego vraga’. Deportatsionnaia politika Rossii 1914-1915, in: Pervaia mirovaia voina i uchastie v nei Rossii 1914-1918, Volume 1, Moscow 1994, pp. 51-64; Bakhturina, Politika rossiiskoi imperii [The Politics of the Russian Empire] 2000, pp. 190-1; Vakareliyska, Cynthia M.: Due Process in Wartime? Secret Imperial Russian Police Files on the Forced Relocation of Russian Germans during World War One, Nationalities Papers, 37/5 (2009), pp. 589-611.

- ↑ Gatrell, A Whole Empire Walking 1999, pp. 16-17; Lohr, Nationalising the Russian Empire 2003, p. 138, pp. 146-7, 150-2; Sanborn, Military Occupation 2011, p. 51.

- ↑ Quoted in Üngör, Uğur Ümit: The Making of Modern Turkey. Nation and State in Eastern Anatolia, 1913-50, Oxford 2011, p. 45; see also Dündar, Fuat: Pouring People into the Desert. The ‘Definitive Solution’ of the Unionists to the Armenian Question, in: Suny / Göçek / Naimark (eds.), A Question of Genocide 2011, pp. 276-84.

- ↑ Quoted in Akçam: Young Turks' Crime Against Humanity 2012, p. 130; Holquist, Peter: The Politics and Practice of the Russian Occupation of Armenia, 1915-February 1917, in: Suny / Göçek / Naimark (eds.), A Question of Genocide 2011, pp. 151-74.

- ↑ Quoted in Mann: Dark Side of Democracy 2005, p. 155.

- ↑ Quoted in Akçam: Young Turks' Crime Against Humanity 2012, p. 135.

- ↑ Akçam: Young Turks' Crime Against Humanity 2012, pp. 68, 115, 201, 231, 357-61, and the map of deportation routes at pp. xxxiv-v; Dündar, Pouring People into the Desert 2011.

- ↑ A leaflet, To the Friends of Humanity (1916?) spoke of a “process of extermination … wiping out an entire people”, MRL2, Series 1, Box 1, Folder 1, Near East Relief Committee Records, The Burke Library Archives, Columbia University Libraries, at Union Theological Seminary, New York. American missionaries also described “complete extermination” in Diyerbekir. William S. Dodd, letter dated 8 September 1915, as above, Folder 5, as above. A statement in August 1916 from W.W. Peet (a missionary attached to Bible House, Constantinople since 1877) spoke of what “appears to be a governmental principle to allow them to die of hunger … systematic annihilation through hunger”, as above Folder 7. See also Barton, James L.: ‘Turkish Atrocities’. Statements of American Missionaries on the Destruction of Christian Communities in Ottoman Turkey, 1915-1917, Ann Arbor 1998.

- ↑ Notes in MRL2, Series 1, Box 2, Folder 4, as above.

- ↑ Rockwell’s notes are in MRL2, Series 1, Box 2, Folder 7, as above.

- ↑ Akçam, Young Turks' Crime Against Humanity 2012, pp. 258-9, 270.

- ↑ In the wake of the Russian advance into Anatolia in 1916, Tsarist officials described ‘repatriated’ refugees as ‘agricultural pioneers’. Notes made by Dr. Samuel G. Wilson, Erevan, 25 December 1915, Folder 4, as above. See also Holquist, Politics and Practice 2011, pp. 159-63.

- ↑ Buttino, Marco: Politics and Social Conflict During a Famine. Turkestan Immediately After the Revolution, in: Buttino, Marco (ed.): In a Collapsing Empire. Underdevelopment, Ethnic Conflicts, and Nationalisms in the Soviet Union, Milan 1993, pp. 257-77; Olcott, Martha Brill: The Kazakhs, Stanford 1995, pp. 121-37.

- ↑ Liulevicius, War Land 2001, pp. 89-112.

- ↑ Üngör, The Making of Modern Turkey 2011; Kontogiorgi, Elisabeth: Population Exchange in Greek Macedonia. The Rural Settlement of Refugees 1922-1930, Oxford 2006.

- ↑ Anderson, Margaret Lavinia: Who Still Talked about the Extermination of the Armenians? German Talk and German Silences, in: Suny/Göçek/Naimark (eds.), A Question of Genocide 2011, p. 216.

- ↑ Opfer, Im Schatten des Krieges 2005; Westerhoff: A Kind of Siberia 2013.

- ↑ I am grateful to Peter Holquist and Christian Westerhoff for their willingness to share work in advance of publication. Thanks are also due to Betty Bolden and Brigette Kamsler at the Burke Library and Archives, Union Theological Seminary, New York.

Selected Bibliography

- Bakhturina, A. I︠U︡.: Politika Rossiiskoi Imperii v Vostochnoi Galitsii v gody Pervoi mirovoi voiny, Moscow 2000: AIRO-XX.

- Bianchi, Bruna (ed.): La violenza contro la popolazione civile nella Grande guerra. Deportati, profughi, internati, Milan 2006: UNICOPLI.

- De Schaepdrijver, Sophie: Military occupation, political imaginations, and the First World War, in: First World War Studies 4/1, 2013, pp. 1-5.

- Gatrell, Peter: A whole empire walking. Refugees in Russia during World War I, Bloomington 2011: Indiana University Press.

- Holquist, Peter: The role of personality in the first (1914-1915) Russian occupation of Galicia and Bukovina, in: Dekel-Chen, Jonathan L. (ed.): Anti-Jewish violence. Rethinking the pogrom in East European history, Bloomington 2010: Indiana University Press, pp. 52-73.

- Liulevicius, Vejas Gabriel: War land on the Eastern front. Culture, national identity and German occupation in World War I, Cambridge 2000: Cambridge University Press.

- Lohr, Eric: Nationalizing the Russian Empire. The campaign against enemy aliens during World War I, Cambridge 2003: Harvard University Press.

- Prusin, Alexander Victor: Nationalizing a borderland. War, ethnicity, and anti-Jewish violence in east Galicia, 1914-1920, Tuscaloosa 2005: University of Alabama Press.

- Suny, Ronald Grigor / Göçek, Fatma Müge / Naimark, Norman M. (eds.): A question of genocide. Armenians and Turks at the end of the Ottoman Empire, Oxford; New York 2011: Oxford University Press.

- Westerhoff, Christian: Zwangsarbeit im Ersten Weltkrieg. Deutsche Arbeitskräftepolitik im besetzten Polen und Litauen 1914-1918, Paderborn 2012: Schöningh.