Introduction↑

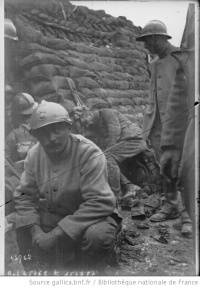

Foot soldiers represented every army’s basic offensive arm in 1914. Their pre-war training focused primarily on marksmanship, the bayonet and discipline. Pre-war infantry tactics emphasized successive attack waves using speed and ferocity to achieve battlefield objectives. Modern industrial weaponry such as breech-loading artillery, machine guns and bolt-action rifles granted tremendous advantages to the defender during the First World War. Furthermore, most armies employed an elastic defense by 1917. This defense-in-depth tactic, introduced by the Imperial German Army in late 1916, involved defenders allowing attackers to capture lightly manned forward trenches so they could decimate them with machine gun fire and counterattacks from well-fortified rear trenches. Attackers grappled with the tactical challenges of surviving “no man’s land,” dislodging an entrenched enemy, and restoring mobility to the battlefield. The rigid mass infantry assault tactics from the previous century resulted in heavy losses against superior defensive firepower in 1914. Unable to move forward, armies entrenched by 1915 and developed trench warfare tactics for the purpose of advancing from one trench to the next in the face of intense firepower. These tactics resulted in only modest territorial gains in 1915 and 1916. By the last two years of the war, however, most tactical doctrines featured more sophisticated infantry techniques for breaking the trench warfare stalemate, such as flexible formations, fire-and-maneuver and infiltration. Eventually, armies integrated advanced weapons and combined arms into these new offensive tactics.

Flexible Formations↑

By 1917, all armies were replacing ridged mass infantry attack formations with smaller, more flexible columns and skirmish lines for the purposes of maneuverability and safety from enemy fire. Lieutenant General Ivor Maxse (1862-1958) made flexible formations a permanent feature of British Army infantry doctrine when he became Inspector General of Training in 1918. Maxse advocated for platoons to advance in columns with five to six yards between each soldier. United States Army tactical publications prescribed small, flexible, single or double file infantry columns instead of long rigid lines when traversing ground under enemy fire in 1918.

Fire-and-Maneuver↑

Opposing artillery, machine guns and barbed wire made it necessary to support offensive infantry maneuvers with firepower. Fire-and-maneuver involved one group of soldiers directing fire against an enemy position while another group maneuvered to converge upon that position from the flank or rear. The fire element suppressed the defenders as the maneuver element attacked and neutralized them. Early in the war, Imperial German Army infantry assault teams took turns firing and advancing. One group of soldiers drew enemy fire while the other moved forward. By 1917, the French Army called for attackers to support one another with suppressing fire as they moved from cover to cover until they were near enough to engage the enemy in close combat.

Infiltration↑

Armies started experimenting with infiltration tactics in 1915. The purpose of infiltration was for infantry to take advantage of the successes of an attack and sidestep the failures. Exploiting breaches as rapidly as possible overwhelmed defenders and prevented them from regrouping and counterattacking. Major Wilhelm Rohr (1877-1930) pioneered infiltration tactics in the Imperial German Army in 1916 and 1917. Mobile infantry units broke through weak points in enemy lines, attack units exploited these gaps, and fortification units consolidated gains. The Imperial German Army used these “storm trooper” tactics to advance up to forty miles in just a few days during the Spring Offensives in 1918. By 1917, French infantry assault tactics called for platoons to advance in surges. The first surge neutralized enemy defensive positions and machine guns. The second surge penetrated enemy lines and captured ground. The third surge consolidated territorial gains. United States Army infantry doctrine described the first assault surge circumventing enemy strong points and leaving them for subsequent attack surges. The first surge held captured ground until reinforcements arrived. The second assault surge avoided stacking behind units that were stalled by enemy resistance and passed through breaches in the enemy line.

Advanced Weapons and Combined Arms↑

Four years of trial and error on the battlefield led the armies of the First World War to fuse new offensive infantry tactics with advanced weapons in their attempts to break through and exploit strong defenses. The Imperial German Army armed its assault teams with grenades, portable machine guns and flamethrowers by 1916. United States Army tactical doctrine combined automatic rifles, grenades and mortars with fire-and-maneuver. American automatic riflemen suppressed enemy strong points while attackers used grenades and stokes mortars as they outflanked them. Infantry eventually became part of an increasingly sophisticated combined arms scheme that included artillery, tanks and aircraft. The Imperial German Army introduced the creeping barrage in 1916. A creeping barrage involved the infantry advancing behind a protective curtain of artillery fire. Over 300 tanks supported the British Army’s minor breakthrough at Cambrai in 1917. French Army doctrine in 1917 described aircraft providing support for the infantry by observing, strafing and bombing enemy targets on the ground. By the end of the First World War, infantry tactics had moved far beyond the 19th century and began to reflect those of the Second World War.

Jeffrey LaMonica, Delaware County Community College

Section Editor: Mark E. Grotelueschen

Selected Bibliography

- Foley, Robert: Learning war’s lessons. The German army and the Battle of the Somme 1916, in: The Journal of Military History 75/2, 2011, pp. 471-504.

- Griffith, Paddy: Battle tactics of the Western Front. The British Army's art of attack, 1916-18, New Haven 1994: Yale University Press.

- Grotelueschen, Mark E.: The AEF way of war. The American army and combat in World War I, Cambridge; New York 2007: Cambridge University Press.

- Gudmundsson, Bruce I.: Stormtroop tactics. Innovation in the German Army, 1914-1918, New York 1989: Praeger.

- Krause, Jonathan: Early trench tactics in the French Army. The Second Battle of Artois, May-June 1915, Farnham 2013: Ashgate.

- Samuels, Martin: Command or control? Command, training, and tactics in the British and German armies, 1888-1918, London 1995: Frank Cass.

- Stachelbeck, Christian: Militärische Effektivität im ersten Weltkrieg. Die 11. Bayerische Infanteriedivision 1915-1918, Paderborn 2010: Schöningh.