Overview↑

Brazil was the main immigration country for German-speaking immigrants to Latin America. From the 1820s to the 1930s, around 200,000 of them arrived in Brazilian ports. In Southern Brazil, German-speaking peasants settled as farmers and came to constitute a large population over time. Middle-class merchants and industrialists formed another important group in the cities and founded German-speaking societies and newspapers there. German pastors, teachers and diplomats were sent by German societies and authorities to Southern Brazil in order to work for the preservation of Deutschtum (Germanness) and strengthen German economical and political influence in the region. They founded schools and churches, and tried to preserve the German language.

The German Peril↑

These activities provoked skepticism among certain Brazilian politicians and intellectuals who criticized the slow assimilation of the immigrants and the attempts to preserve Deutschtum. Around 1900, Brazilian newspapers even issued a warning against the alleged “German peril” (perigo alemão). Following U.S. American and French propaganda, they expressed the fear that Germany could annex Southern Brazil. The most influential text was “The Allemanism in the South of Brazil” by Sílvio Romero (1851-1914) from 1906. Romero and others cited colonialist texts from Germany in order to prove their argument. In turn, the German-speaking elites in Brazil accused the Brazilians of being nativist.

On 26 November 1905, the so-called “Panther-incident” aggravated the situation: Crew members of the German gunboat “Panther” which was visiting the Brazilian coast were searching for a deserted mariner in Itajaí, Santa Catarina state and arrested him under dubious circumstances. The Brazilian press condemned the incident as a violation of Brazilian sovereignty. Germany denied these reproaches but had to apologize officially to the Brazilian government.

German Immigrants and the War↑

The entanglements between Germany and the German-speaking elites in Brazil re-asserted themselves when World War I broke out. Many German and Austrian nationals were called up immediately and had to return to Europe. The majority of the German-speaking press declared their solidarity with the German Empire, reported extensively about the war and published propaganda against the British and French, using German press agencies like Transocean.

The events in Europe led to an enforced identification with Deutschtum. German-speaking Brazilians organized meetings, rogation services and collection campaigns for the German Red Cross. Various local societies and newspapers advertised German and Austrian-Hungarian war bonds which were purchased frequently. Also the Kriegsnotspende (urgent war donation) was promoted, and teachers at German-speaking schools even collected funds in classroom.

Of course, this did not mean that every immigrant or descendant of immigrants was a German nationalist and supported the war. On the contrary: When the Helvetian pastor and envoy of the German Red Cross Gottlieb Zimmerli tried to unite all immigrants from Central and Northern Europe in the Germanischer Bund für Südamerika (Germanic Union for South America) in 1916 in order to support the Central Powers, the most important German-speaking societies in Southern Brazil refused to participate. A sharp conflict occurred between the influential Federation of German Societies in Porto Alegre and the Bund, since the German-speaking elites were not interested in being instrumentalized for political aspirations. They saw themselves as Brazilians and tried to avoid every action that could provoke nativist reactions.

Conflicts and Riots↑

Their hesitance was with good reason: Prior to and during World War I, various propaganda publications, written by famous writer Graça Aranha (1868-1931) among others, renewed the idea of the German peril and connected it with the war. These texts suggested that the German immigrants could be a threat for national security because they showed German national symbols in public and were organized in shooting associations.

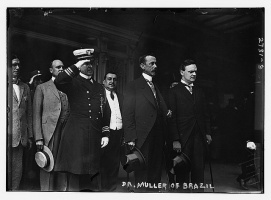

Germanophile politicians constituted only a minority, among them Foreign Minister Lauro Müller (1863-1926) who had German-speaking ancestors, and João Dunshee de Abranches (1867-1941) who published pro-German propaganda texts that denounced the German peril as an U.S. American myth. Another Germanophile was diplomat Manoel de Oliveira Lima (1867-1928), whose diplomatic post in London was refused by the Brazilian senate due to his political stance.

Everyday life, too, was influenced more and more by tensions, due to the sympathy which the majority of the Brazilian society had with and for the Allies. In 1915, the Liga Brasileira pelos Aliados (Brazilian League for the Allies) was founded and organized demonstrations and propaganda against the Central Powers. Prominent members were the writer José Veríssimo (1857-1916) and the politician Rui Barbosa (1849-1923) who also joined the Liga da Defesa Nacional (League for National Defense) which was founded the following year and tried to strengthen Brazilian patriotism and demanded the armament of Brazil.

When the Brazilian ship Paraná was torpedoed by German submarines on 5 April 1917, Brazil broke off diplomatic relations with the German Empire on 11 April and confiscated all German ships that anchored in Brazilian ports. Anti-German protests occurred in the big cities, and in Porto Alegre, the capital of the southern-most state Rio Grande do Sul where the most German-speaking immigrants lived, a mob destroyed around 300 German and German-Brazilian houses and businesses between 14 and 16 April. Among them were the “Germania,” the most prestigious German clubhouse, and the editorial offices of the newspaper Deutsche Zeitung. Riots also occurred in other regions of Rio Grande do Sul.

Declaration of War and Nationalization Measures↑

After German submarines had sunk another three Brazilian ships, Brazil declared war against Germany on 26 October 1917. Again, demonstrations and riots against Germany and German-speaking Brazilians took place, this time in the cities of Curitiba and Pelotas. That same year, many companies with German names renamed themselves in order to continue their businesses.

The Brazilian government issued several laws that banned German-speaking activities in the country. German-speaking schools, church services and newspapers were prohibited and German-speaking societies were shut down. While this nationalization policy was not implemented everywhere, it still led to a rupture of German-speaking cultural life and German efforts to preserve Deutschtum in Brazil until 1919 when the bans were lifted.

Aftermath↑

After the war, the German-speaking Brazilian elites continued to stand solidly behind Germany. They sent aid packages to Germany and participated in the Ruhrspende (Ruhr donation) when France occupied the Ruhr region in 1923. The German-speaking press condemned the Treaty of Versailles and discussed the fate of the Germans abroad (Auslandsdeutsche). In Porto Alegre, former German soldiers founded a German Veterans' Association (Deutscher Kriegerverein) and erected a monument commemorating the killed German soldiers.

Frederik Schulze, Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster

Reviewed by external referees on behalf of the General Editors

Selected Bibliography

- Lesser, Jeff: Immigration, ethnicity, and national identity in Brazil, 1808 to the present, Cambridge 2013: Cambridge University Press.

- Luebke, Frederick C.: Germans in Brazil. A comparative history of cultural conflict during World War I, Baton Rouge 1987: Louisiana State University Press.

- Proctor, Tammy M.: 'Patriotic enemies'. Germans in the Americas, 1914-1920, in: Panayi, Panikos (ed.): Germans as minorities during the First World War. A global comparative perspective, Burlington 2014: Ashgate, pp. 213-233.

- Silva, Haike Roselane Kleber da: Entre o amor ao Brasil e ao modo de ser alemão. A história de uma liderança étnica (1868-1950) (Between love to Brazil and the way to be German. The history of an ethnic leadership (1868–1950)), São Leopoldo 2006: Oikos Editora.

- Skidmore, Thomas E.: Black into white. Race and nationality in Brazilian thought, New York 1974: Oxford University Press.