Early Life↑

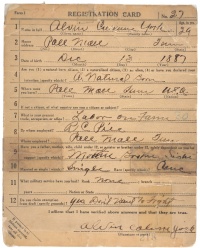

Albert Cullum York (1887-1964), one of eleven children, was born into a poverty-stricken family in the Appalachian backcountry of eastern Tennessee. While still in his teenage years, York had to support his family by taking on blacksmithing and labor jobs after the death of his father. During his early adulthood, York had regular brushes with the law due to his penchant for heavy drinking and violent behavior. In January 1915, York, who had regularly attended church, converted and joined the Churches of Christ in Christian Union. As a consequence, he abandoned his hedonistic lifestyle and in time became a respected leader in his local church. After receiving a draft notice in June 1917, he requested an exemption as a conscientious objector, citing the Christian Bible’s injunction against killing. The exemption board denied York’s appeals, and he was inducted into the army in November 1917.

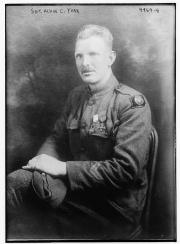

Military Service↑

Training↑

Alvin York embarked to Camp Gordon, Georgia to join the 328th infantry, 82nd division.[1] During his training, he continued to struggle to reconcile his beliefs with a soldier’s duty to kill. York shared his doubts with his battalion commander, Major George Buxton (1880-1949), who quoted Scripture to support the concept of fighting as part of a just war. Only after a period of home leave, devoted to prayer and fasting, did York reconcile his beliefs with his duty to fight.

Overseas, York’s division completed its final training with the British. The 82nd division defended the Woëvre region from June to August 1918, where Private York earned promotion to corporal for his leadership of an automatic rifle team. Afterwards, the 82nd division fought in the St. Mihiel offensive during September 1918.[2]

Meuse-Argonne↑

On 7 October 1918, the 82nd division entered the Meuse-Argonne offensive, attacking to relieve the “Lost Battalion” of the 77th division.[3] However, Corporal York’s battalion’s attack near Châtel-Chéhéry on 8 October 1918 stalled under concentrated machine gun and artillery fire. York’s platoon, commanded by Sergeant Bernard Early (1893-1976?), was ordered to take a patrol to outflank the enemy machine guns holding up the advance. After some initial success, the American patrol was hit with German machine gun fire during an attempt to withdraw with some prisoners. Corporal York, protected by a fold in the ground, began to kill the German machine gunners with unnervingly accurate rifle fire, while calling on the rest to surrender. Faced with a German counterattack, he killed the entire group of six men with a semiautomatic pistol, after which the surviving German officer surrendered with an estimated eighty to ninety men.[4] York gathered up his surviving American riflemen, and using the enemy officer as a shield, swept up additional prisoners while returning to friendly lines. Corporal York personally killed twenty-five enemy soldiers with a pistol and rifle, while the patrol successfully broke the enemy defenses, with the capture of four officers and 128 men, leaving some thirty machine guns abandoned on the battlefield.[5]

With his experiences in combat deeply affecting him, York obtained permission to return to the battlefield in a fruitless attempt to rescue survivors. Maintaining his religious conviction, he also prayed for the dead and wounded on both sides.[6] Shortly thereafter, Corporal York earned promotion to sergeant and received the Distinguished Service Cross. During a postwar review of valor awards, an investigative panel determined that Sergeant York’s actions merited a Medal of Honor, which was awarded on 18 April 1919. When asked by the investigating general how he had accomplished such a feat, York replied “it was not man-power but it was divine power that saved me.”[7]

Postwar Life and Controversy↑

The American Expeditionary Forces made no effort to publicize Sergeant York’s exploits, but a reporter learned of the story, and talked his way into walking the battlefield with York and the investigative team. The resulting Saturday Evening Post article in April 1919 made Sergeant York a powerful cultural symbol for Americans, a devout but reluctant citizen-soldier, whose prowess with the rifle outmatched the professional soldiers of the Kaiser’s army. However, some members of York’s patrol disputed the story, stating that they had also played a significant role in the engagement; assertions that the investigating board rejected.[8] The army discharged York in mid-1919 after a tour of New York City and Washington, D.C., where the public feted him as a hero. York rejected opportunities to profit from his fame, and instead turned to activism to improve the lot of his home region.

The controversy over York’s exploits widened in the 1920s with German articles that minimized York’s accomplishments and the extent of the German losses.[9] During the interwar period, York’s efforts to improve the infrastructure and education of his home region were marred with debt and controversy. In a reversal from his prewar pacifism, York eventually clashed publicly with prominent isolationists like Colonel Charles Lindbergh (1902-1974) over United States policy towards the rising tide of fascism in the 1930s. York’s shift in attitude towards war readiness was reflected in the Sergeant York film. Released shortly before the Pearl Harbor attack in December 1941, the movie garnered numerous Academy Awards and boosted military recruitment. For York, the movie worsened his financial woes, enmeshing him in a years-long dispute with the Internal Revenue Service over unpaid taxes.

During World War II, York obtained a major’s commission in the army’s signal corps, but his poor physical condition limited his wartime service to stateside training camp visits and war bond rallies. His postwar years were marked by additional financial woes, and a rapid decline in his health before his death on 2 September 1964.[10]

Harold Allen Skinner Jr., United States Army Reserve

Section Editor: Lon Strauss

Notes

- ↑ American Battle Monuments Commission: 82d Division, Summary of Operations in the World War, Washington, D.C. 1944, p. 1.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 2, 7-8.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 17.

- ↑ Skeyhill, Tom (ed.): Sergeant York. His Own Life Story and War Diary, New York 2018, p. 218.

- ↑ Mastriano, Douglas: Alvin York. A New Biography of the Hero of the Argonne, Lexington 2014, pp. 107-114.

- ↑ Lee, David C.: Sergeant York. An American Hero, Lexington 1985, p. 43.

- ↑ Mastriano, Alvin York 2014, pp. 134-137.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 139-140.

- ↑ Lee, Sergeant York 1985, pp. 42-44.

- ↑ Mastriano, Alvin York 2014, pp. 215-216. In 2014, historian Douglas V. Mastriano released an updated biography about Alvin York, in which analysis of German and American primary source documents, and battlefield archaeological surveys, were used to corroborate York’s version of the events of 8 October 1918.

Selected Bibliography

- American Battle Monuments Commission: 82d division, summary of operations in the world war, Washington, D.C. 1944: United States Government Publishing Office.

- Lee, David D.: Sergeant York. An American hero, Lexington 1985: University Press of Kentucky.

- Mastriano, Douglas V.: Alvin York. A new biography of the hero of the Argonne, Lexington 2014: University Press of Kentucky.

- Mastriano, Douglas V.: Thunder in the Argonne. A new history of America's greatest battle, Lexington 2018: University Press of Kentucky.

- Skeyhill, Tom (ed.): Sergeant York. His own life story and war diary, New York 2018: Racehorse Publishing.