Introduction↑

The First World War coincided with a Progressive Era of domestic reform within the United States that included a seventy-year struggle for equal suffrage, industrial expansion and extensive immigration and migration. American participation in the conflict challenged the notions of men as protectors and women as the protected. Women claimed expanded rights of female citizenship through employment, voluntary service to the state, and woman suffrage. Other activist women used their voices to challenge the United States participation in the war. Wartime activism contributed to enhanced civic rights for women and, for many, a transnational approach to activism followed the conflict.

Women’s Role in Peace Movement↑

The United States officially observed the first years of the war in Europe from 1914 to April 1917 as a neutral nation, but many residents identified with the Allied cause. The preparedness movement sought to ready young Americans for war through military drill and mobilization in schools and communities. Preparedness advocates argued that women could best serve the nation as “patriotic mothers” who raised their children to support and defend the nation.[1] Other women, including those who were involved in the Progressive Era peace movement, challenged preparedness with the view that women suffer the violent consequences of war and should organize to oppose it. Women involved in the Socialist Party and organized labor movements most often viewed war as an aid to capitalist profits and imperialism.[2]

When war began in Europe in the summer of 1914, 1,500 American women protested in a silent march through the streets of New York City. Frustrated by the lack of response from male colleagues in the peace movement, Fannie Garrison Villard (1844-1928), Crystal Eastman (1881-1928), and Madeline Z. Doty (1877-1963) of New York began to organize what would become the first all-female peace organization in the United States, the Woman’s Peace Party.[3] Once the United States entered the war in 1917, female pacifists established legal assistance for male conscientious objectors, draftees, and those who violated wartime restrictions on civil liberties such as free speech. These women helped to establish a “peace culture” that “flourished” in the face of powerful political pressures to militarize America.[4]

During the conflict the United States Congress, executive branch, and judicial system supported anti-civil liberties legislation and policies, including the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918 that removed freedoms of speech and criminalized challenges to the war effort and the draft. In this repressive climate, women who did not conform to the strictures of patriotic motherhood were prosecuted and persecuted as disloyal and dangerous. New York anti-war activist Emma Goldman (1869-1940) believed that the military draft was the antithesis of democracy and created the No Conscription League to educate men and women about the draft and to support conscientious objectors. She was imprisoned and eventually deported. Marie Equi (1872-1952), M.D. of Portland, Oregon, received harsh treatment from the Justice Department for her open loving relationship with another woman in addition to her critique of the war and was sent to San Quentin prison. Kate Richards O’Hare (1877-1948) made claims that the Wilson administration was exploiting women by sending their sons to war; this garnered her a conviction in North Dakota.[5]

Many U.S. women were involved in the post-war peace and disarmament movements and then developed a transnational identity and approach, working above and across national borders with international labor organizations, women’s groups, and medical humanitarian relief. In 1919 the Women’s Peace Party became the United States section of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom.[6]

Female Participation in the Preparedness Movement↑

At the same time that some U.S. women worked to oppose the war in Europe and military preparedness, others joined associations that militarized women into shooting clubs and paramilitary organizations. Groups such as the Women’s Section of the Navy League and the National League for Women’s Service embraced the role of the patriotic mother in their preparedness activities.[7] Other female supporters of military preparedness took a different view of female citizenship. They hoped to create female army units and embrace the traditional male citizen’s obligation to take up arms to serve the nation.

Other women interested in preparedness emphasized that war brought violent consequences for women and that women faced intimate violence in war and peace. Self-defense was, for them, a right of female citizenship and a challenge to male violence.[8] The largest of the over thirty-nine U.S. women’s rifle and paramilitary organizations was New York’s American Women’s League for Self-Defense (AWLSD), organized in 1916. Women members engaged in cavalry and infantry training. Many preparedness groups sponsored summer camps along the lines of the Plattsburg camps that trained college and business men in these skills. Popular women’s magazines noted group activities. The Delineator, a magazine popular for patterns and recipes before the war, featured a “women’s preparedness” column throughout 1917 with news of training camp activities around the country.[9]

Female Voluntarism and Wartime mobilization↑

When the United States entered the conflict in April 1917, the administration needed the loyalty of a divided nation, including the vital support of women on the home front. Women’s clubs had been flourishing in the United States Progressive Era since the 1890s, and the Woman’s Committee of the United States Council of Defense, headed by former National American Woman Suffrage Association president Anna Howard Shaw (1847-1919), harnessed women’s energy and linked the networks of women’s clubs already in place with this umbrella organization. They supported the military with the production of knitted goods and bandages, food conservation, and fundraising.[10]

Hundreds of thousands of U.S. women worked with voluntary agencies on the home front, and over 6,000 women volunteered for service abroad, including work with the Red Cross, the Young Women’s Christian Association (Y.W.C.A.), the Jewish Welfare Board, and the American Library Association. Women involved in the Commission for Training Camp Activities worked to identify venereal disease as a wartime problem and staffed Y.W.C.A. Hostess Huts and canteens at home and in France in an effort to police sexuality to help “make men moral.”[11]

Woodrow Wilson's (1856-1924) administration and the leaders of these groups put strong pressure on U.S. women to volunteer for wartime service. “Coercive volunteerism” framed female citizenship in terms of absolute loyalty to the nation but also provided a civic role for patriotic women’s service. Women who knitted and rolled bandages were also providing free labor for the military. And under the direction of the United States Food Administration, “kitchen soldiers” conserved vital commodities for the War effort.[12]

Wartime propaganda in posters, songs and news accounts combined with organizational policies defined American women who volunteered for service abroad as patriotic mothers and sisters. The Red Cross, Salvation Army, the Young Men’s Christian Association (Y.M.C.A.) and the Y.W.C.A. placed men in positions of administrative authority and decision making, and reserved female managerial posts for older women. Women who worked in canteens and in other direct voluntary work with soldiers faced “a contradictory set of expectations in regard to their conduct.” Supervisors encouraged them “to be pleasing to the men, as long as their interest appeared impersonal.” But officials were “quick to condemn” women for actions that could be interpreted as flirtatious or sexual in nature.[13] Such behavior was a violation of the code of patriotic motherhood and sisterhood.

Women of Color and Women in Minority Communities↑

The First World War created a context for women who were members of racial and ethnic minority communities to establish claims for citizenship and civic rights through wartime service. The years from 1916 to 1918 marked years of strength and influence for African American clubwomen who “combined prowar sentiments and antiracist protests” to claim full citizenship in the “unusual political space” brought on by wartime. The National Association of Colored Women provided support for women “in war work, financial assistance, and institutional guidance” and across the nation.[14] African American women supported black troops and their families with knitting, supplies, and fundraising, and established local branches of the Emergency Circle of Negro War Relief. African American women also filed lawsuits to challenge racial segregation in employment and restaurant and lunch counter service and protested the East St. Louis Riot of 1917 with a vigorous public-awareness campaign, silent marches and prayer meetings.[15] In Los Angeles, California, women worked within ethnically segregated auxiliaries of the Red Cross. Japanese American and Jewish women established auxiliary sections and at Brownson House, a settlement house under Catholic auspices, Mexican American women organized for Red Cross service. African American women worked within the Harriet Tubman and the Phyllis Wheatley Red Cross auxiliaries.[16]

African American women who served in France with segregated African American units challenged the racial and gendered hierarchies of the war. In their work with the Y.M.C.A., Addie Waites Hunton (1866-1943) and Kathryn Johnson (1878-1955) provided support services for African American troops, and challenged government segregation working as both “race women and cultural ambassadors.” In Two Colored Women with the American Expeditionary Forces (1920), Hunton and Johnson recounted the important contributions of African American soldiers and female relief workers in the face of racial discrimination.[17] Hunton used the paradigm of patriotic motherhood but also subverted it to “foster” in the men under her motherly care in France “a political consciousness that was critical of the nation” and made a claim for African American women’s service on equal terms with white women and with men.[18]

Women Physicians↑

In the United States, members of the Medical Women’s National Association (MWNA), established in 1915, worked across the war years to gain officer status for female physicians in the Army Medical Corps. Though their efforts were not successful, many women doctors expressed their desire for service as part of their claims for a more complete citizenship and professional identity.[19] Women’s organizations established all-female medical units for wartime service in France. The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) sponsored the Women’s Oversea Hospitals with two units in France and members of the MWNA staffed and funded two French units and dispensaries under the auspices of the American Women’s Hospitals.[20] At least seventy-six other women physicians served at the home front and with voluntary organizations overseas by the close of the conflict in November 1918. Fifty-five women physicians served in the army medical corps as temporary contract surgeons: eleven served overseas and forty-five worked in U.S. states and territories, including Puerto Rico.[21]

Physician and suffrage activist Esther Pohl Lovejoy (1869-1967), from Portland, Oregon, was the first woman to serve on the American Red Cross Commission to France. With the backing of U.S. women’s organizations, including the Woman’s Committee of the Council of National Defense, she worked at a Paris settlement house and investigated conditions for French women refugees. She identified the particular violence against women that came with modern warfare, and sought to link the work of U.S. women physicians with their counterparts in Europe and elsewhere. In 1919 she was an organizer and first president of the Medical Women’s International Association, and she developed the American Women’s Hospitals into a consequential medical humanitarian relief organization in the post-war years.[22]

Women Nurses↑

There were far more female nurses in the United States than there were women physicians. Nurses’ medical skills were in high demand by the U.S. government and voluntary organizations, but their claims for military rank were not entirely successful by the close of the conflict. The War Department had organized the Army Nurse Corps in 1901 and the Navy Nurse Corps in 1908, while the American Red Cross was the reserve for the military nursing corps during the war. Over 21,480 women served in the Army Nurse Corps during the War, 10,660 of them with the American Expeditionary Force abroad, and some 1,500 women served with the Navy Nurse Corps by November 1918.[23]

National nursing leaders were molding a profession based not only on training and skill, but also on a class- and race-based gender code of respectability. Their professional vision focused on training schools for women nurses that would separate graduates from unskilled and poorly paid domestic workers. Leaders worked to create a respectable cadre of nurses who were daughters of the middle class or women whose nursing training would give them middle class status. They emphasized a formula of selfless service, sexual purity, loyalty and obligation, all traits that leaders hoped would bring public acceptance of nursing professionalism. Nursing continued to be considered women’s work during the war.[24]

In the United States, white nurses were the only group of women employed by the military for the entire length of the conflict. African American nurses worked for the length of the war to gain inclusion into the Red Cross and Army Nurse Corps, led by New York’s Adah Thoms (1870-1943). With the crisis of the influenza pandemic in the fall of 1918, eighteen African American nurses were accepted into the Army Nurse Corps for service in two training camps for African American soldiers, Camp Sherman in Ohio and Camp Grant in Illinois.[25] The Army Nurse Corps had 134 deaths and the Navy Nurse Corps had nineteen during the period of the war, many from the influenza pandemic.[26]

Nurses and their supporters mounted a campaign to change military regulations so that all army nurses would be commissioned as officers, from the entry level of second lieutenant to the rank of major for the Superintendent of the Army Nurse Corps. Nursing leaders and advocates for suffrage and women's rights organized the Committee to Secure Rank for Nurses in 1918. In 1920 the War Department decided to create “relative rank” for U.S. military nurses, providing for semi-officer status. They could wear the insignia of office but did not receive the same pay as male officers and did not have the authority to command men.[27]

Women in Other Military Jobs↑

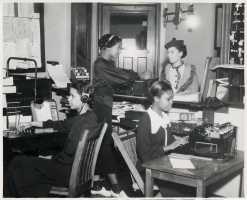

Over 12,000 women worked for the United States Navy and Marine Corps as Yeomen (F) in clerical and recruiting positions and in naval intelligence. Yeomen (F) challenged U.S. naval policy, including the provision for health care for women in the military. Some women requested and were granted release from duties to care for children and parents. But the navy did not adjust policies to provide for childcare for women on the job, and pregnant women were discharged.[28] Several thousand other women worked for the U.S. Army abroad and in the States as clerical workers and telephone operators as part of the Signal Corps.[29] The Army Medical Corps employed 2,000 women physical and occupational therapists – known as Reconstruction Aides – as civilian employees, 300 of them in France.[30]

U.S. Women Workers on the Home Front↑

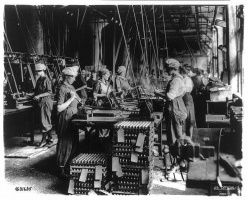

The First World War also expanded female opportunities for wage work on the United States home front. The war merged with ongoing Progressive Era debates and activism about protective labor legislation for women, equal pay for equal work for women and men, and workplace safety issues for all workers. The war also coincided with a maturing industrial system in America, vast immigration and migration, and challenges to the industrial system by labor unions, Socialists, and other reformers.[31] Women workers during the war challenged gender stereotypes as they made claims on the wartime state for safe workplaces and equal wages with men. They increased the visibility and may have increased the acceptance of women in the wage workforce. The U.S. Department of Labor created the Women in Industry Service to develop and implement wartime standards for women workers in industry such as the principles (if not the realization) of equal pay for equal work and a ten-hour workday. The service became the permanent Women’s Bureau of the U.S. Labor Department in 1920.[32]

The United States participation in the World War brought some 1 million women into the wartime workforce. This represented a growth in the number of women working for wages and also an expansion of the kinds of jobs available, particularly in manufacturing. Women working in railroad jobs, for example, expanded from 31,400 in 1917 to 101,785 the month before the Armistice, working in the roundhouse as sweepers and cleaners, worked the docks, and as machinists and helpers in the machine shop. In addition, women joined labor unions in large numbers with almost 400,000 women organized by 1920. Women stenographers, railroad workers, and telephone and telegraph operators engaged in wartime strikes for better working conditions. Women also shaped management decisions. The U.S. Women’s Bureau reported that twelve plants had hired African American women as supervisors “because their black employees had demanded it of them.”[33]

The World War helped to fuel the Great Migration of African Americans from the South to Northern and Midwestern cities. African American women came singly, as heads of households, or with nuclear and extended families to cities such as New York, Chicago, and Detroit in search of work and an escape from the sharecropping system and poverty of the South. Supported by black women’s clubs and organizations such as Chicago’s Urban League, African American women found work as domestics, in laundries, and in factories, in railroad yards and meatpacking plants. Over the course of the war a few edged their way into clerical jobs in Chicago’s Sears, Roebuck and Company and in Detroit’s automobile plants as inspectors. [34]

The Mexican Revolution and active recruiting from U.S. agribusiness, mining, and railroads brought many Mexicanas and their families to the Southwest. Women worked for wages in urban areas and in agriculture, nurtured their families, and created communities in these wartime workplaces. Women who crossed the U.S. border as single mothers often experienced heightened scrutiny by immigration officials. Provisions of the Immigration Act of 1917 including a head tax, and a test for literacy increased the challenges for Mexican women who sought work in the United States. [35] Immigrant women from Europe were vulnerable on the job to increased scrutiny and hostility as loyalty and “100 percent Americanism” framed wartime policies in the United States.[36]

Some 20,000 women from cities and college campuses joined the Women’s Land Army of America to replace male farmworkers who had gone to war. Coalitions of women’s organizations, including the Y.W.C.A., administrators of women’s colleges, and suffrage groups supported their work. Members of the Women’s Land Army, known as “farmerettes,” dressed in pants and worked from plowing and planting to weeding and harvesting, engaging the admiration of many farm families in the process. They received equal pay for their work with male farmworkers.[37]

Suffrage Movement↑

The years of the First World War and its immediate aftermath witnessed the close of a seventy-two year struggle to achieve woman suffrage in the United States, from the Seneca Falls, New York Women’s Rights Convention in 1848 to the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution in 1920. When the nation entered the First World War in April 1917, eleven U.S. states and one territory provided full voting rights for women.[38] During the final year of the war both houses of the United States Congress approved an amendment to the U.S. constitution that provided for women’s full voting rights. This Nineteenth Amendment was ratified on 26 August 1920.[39]

Historian Sarah Hunter Graham found that “America’s participation in the war both helped and hindered the suffrage cause.” Members of the moderate National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) used the war to their advantage by engaging in patriotic voluntary service that increased their visibility and popularity, thus giving national leaders increased leverage with male politicians as suffrage momentum increased. But the war also hindered the suffrage cause. The wartime emergency suspended lobbying in Washington for a period and war work diverted some of NAWSA’s attention away from suffrage.[40]

During the war leaders of NAWSA “found a nonmilitant lever with which to pressure the government to grant woman suffrage.”[41] Beginning with her 1915 ascendancy to the presidency of NAWSA, Carrie Chapman Catt (1859-1947) inaugurated her “Winning Plan” that combined state-by-state efforts to win voting rights for women with an activist program to pass a woman suffrage amendment to the U.S. Constitution.[42] Catt, a pacifist, decided on a middle ground for NAWSA during the war years: members would work for both woman suffrage and the war effort.

In Washington, D.C. the NAWSA Congressional Committee’s headquarters became a gathering and meeting place for women on the staff of the U.S. Food Administration, the War Department, and relief and nursing groups. NAWSA contributed to Red Cross drives, War Savings Stamp and Liberty Loan Drives. [43] In local communities across the nation, NAWSA supporters followed suit. For example, members of the Dallas, Texas Equal Suffrage Association, affiliated with NAWSA, linked wartime suffrage activism with traditional views of female propriety and community volunteerism. White women activists in this conservative city blunted potential opposition by campaigning for suffrage with familiar symbols and rituals, blending patriotism with political action in county fairs, victory gardens, and Red Cross activity.[44] Members of the Oregon Equal Suffrage Alliance, who had been voting citizens since 1912, sponsored wartime food conservation activities and made their organization a clearinghouse for women’s war work.[45]

The conflict also provided a forum for the more radical National Woman’s Party (NWP) to highlight what they considered the hypocrisy of fighting to make the world safe for democracy when U.S. women could not vote. Members of the National Woman’s Party (NWP) led by Alice Paul (1885-1977) and Lucy Burns (1879-1966), focused entirely on the suffrage cause during the conflict. Members picketed the White House; some 200 protesters were arrested, and many went on hunger strikes and were force-fed by prison officials. Their tactics created some suffrage enemies among legislators and the public, perhaps slowing acceptance of female suffrage.[46] Some historians counter that the radical action and visible protests of the NWP in picketing the White House, made the Wilson administration more anxious to deal with the moderate NAWSA and therefore helped the suffrage cause.[47] After the war the NWP worked for the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, and supported an Equal Rights Amendment to the United States Constitution.[48]

The Nineteenth Amendment did not enfranchise all women. Many Native American women did not have U.S. citizenship until the 1924 Native American Citizenship Act. First generation Asian American women could not become naturalized citizens, and therefore could not vote, until after the Second World War. And federal legislation in place from 1907 to 1922 and upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in Mackenzie v. Hare (1915) mandated that U.S. citizen women who married non-citizen men lost their U.S. citizenship and took on the citizenship of their husbands. They were therefore ineligible to vote.[49] The wartime movement for voting rights was nonetheless one important step toward full citizenship for women in the United States.

Conclusion↑

Women in the United States had many approaches to work, service, and protest during the First World War. Many claimed a more complete female citizenship through working for the vote and service to the state during wartime, including military service. The war became a watershed in women’s wage work from farm to factory to office. Activists in the movement for woman suffrage were divided over support for the conflict, and radical action and moderates’ wartime service both contributed to the achievement of the Nineteenth Amendment enfranchising women in 1920.

Kimberly Jensen, Western Oregon University

Section Editor: Edward G. Lengel

Notes

- ↑ Steinson, Barbara J.: American Women’s Activism in World War I, New York 1982; Kennedy, Kathleen: Disloyal Mothers and Scurrilous Citizens. Women and Subversion During World War I, Bloomington 1999.

- ↑ Early, Frances H.: A World Without War. How U.S. Feminists and Pacifists Resisted World War I, Syracuse 1997.

- ↑ Kuhlman, Erika A.: Petticoats and White Feathers, Westport 1997, pp. 37-39. In 1919 the Women’s Peace Party became the United States section of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. See Kuhlman, Petticoats and White Feathers 1997, p. 119.

- ↑ Early, A World Without War 1997, p. 28 and passim.

- ↑ Kennedy, Disloyal Mothers and Scurrilous Citizens 1999.

- ↑ Kuhlman, Petticoats and White Feathers 1997, p. 119, Jensen, Kimberly and Kuhlman, Erika (eds.): Women and Transnational Activism in Historical Perspective, Dordrecht 2010.

- ↑ Steinson, American Women’s Activism 1982.

- ↑ Jensen, Kimberly: Mobilizing Minerva. American Women in the First World War, Urbana 2008, pp. 36-59.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 42–45, 54, 60–76.

- ↑ Brownell, Penelope: The Women’s Committees of the First World War. Women in Government, 1917-1919, Ph.D. diss. Brown University 2002.

- ↑ Bristow, Nancy K.: Making Men Moral. Social Engineering During the Great War, New York 1996 and Gavin, Lettie: American Women in World War I. They Also Served, Niwat 1997.

- ↑ Capozzola, Christopher: Uncle Sam Wants You: World War I and the Making of the Modern American Citizen, New York 2008, pp. 83-103.

- ↑ Zeiger, Susan: In Uncle Sam’s Service: Women Workers With the American Expeditionary Force, 1917-1919, Ithaca 1999, pp. 51–76, quote p. 67.

- ↑ Brown, Nikki: Private Politics and Public Voices. Black Women’s Activism from World War I to the New Deal, Bloomington 2006, p. 2, p. 9.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 1-29.

- ↑ Dumenil, Lynn: Women’s Reform Organizations and Wartime Mobilization in World War I-Era Los Angeles in The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 10/2 (2011), pp. 235-37.

- ↑ Brown, Nikki: Private Politics and Public Voices, Bloomington 2006, pp. 84-107.

- ↑ Plastas, Melinda: A Band of Noble Women. Racial Politics in the Peace Movement, Syracuse 2011, p. 44.

- ↑ Jensen, Mobilizing Minerva 2008, pp. 75-97.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 98-115.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 86-88.

- ↑ Jensen, Kimberly: Oregon’s Doctor to the World. Esther Pohl Lovejoy and a Life in Activism, Seattle 2012, pp. 122-44.

- ↑ Stimson, Julia C.: The Army Nurse Corps, in The Medical Department of the United States Army in the World War, Pt. 2 of vol. 8, Washington DC 1927; Dock Lavinia L. et al.: History of American Red Cross Nursing, New York 1922; Schneider, Dorothy and Schneider, Carl: Into the Breach. American Women Overseas in World War I, New York 1991; Zeiger, In Uncle Sam’s Service 1999, pp. 104-136; Jensen, Mobilizing Minerva 2008, pp. 119-20.

- ↑ Jensen, Mobilizing Minerva 2008, pp. 118-19.

- ↑ Clark Hine, Darlene: The Call That Never Came. Black Women Nurses and World War I, An Historical Note, in: Indiana Military History Journal 8 (1983), pp. 23–27.

- ↑ Stimson, Army Nurse Corps 1927, p. 311.

- ↑ Jensen, Mobilizing Minerva 2008, pp. 120-41; Zeiger, In Uncle Sam’s Service 1999, pp. 110-11.

- ↑ Ebbert, Jean and Hall, Marie-Beth: The First, the Few, the Forgotten. Navy and Marine Corps Women in World War I, Annapolis 2002.

- ↑ Zeiger, In Uncle Sam’s Service 1999, pp. 77-103.

- ↑ Gavin, American Women in World War I 1997, pp. 101-28.

- ↑ Cott, Nancy F.: The Grounding of Modern Feminism, New Haven 1987, pp. 117-42; Kessler-Harris, Alice: In Pursuit of Equity. Women, Men and the Quest for Economic Citizenship in 20th Century America, New York 2001, pp. 19-63.

- ↑ The Women’s Bureau, Harvard University Library Open Collections Program, Women Working, 1800-1930: http://ocp.hul.harvard.edu/ww/womensbureau.html. (retrieved: 11 November 2012).

- ↑ Weiner Greenwald, Maureen: Women, War and Work. The Impact of World War I on Women Workers in the United States, Westport 1980, quotes p. 93, p. 42.

- ↑ Brown, Carrie: Rosie’s Mom. Forgotten Women Workers of the First World War, Boston 2002, pp. 69-94, p. 149.

- ↑ Ruiz, Vicki: From Out of the Shadows. Mexican Women in Twentieth-Century America, New York 1998, pp. 8-13.

- ↑ Kennedy, Disloyal Mothers and Scurrilous Citizens 1999.

- ↑ Weiss, Elaine F.: Fruits of Victory. The Woman’s Land Army of America in the Great War, Washington D.C. 2008.

- ↑ (Wyoming 1890; Colorado 1893; Idaho and Utah 1896; Washington State 1910; California 1911; Oregon, Kansas, and Arizona, 1912; Montana and Nevada, 1914; the Territory of Alaska, 1913) and some other states provided for local school, tax and bond, and presidential election-only suffrage. From 1917 to 1918 four other states secured full suffrage for women (New York, 1917; Michigan, South Dakota and Oklahoma, 1918), and eleven additional states (North Dakota, Nebraska, Rhode Island, 1917; Indiana, Maine, Missouri, Iowa, Minnesota, Ohio, Wisconsin and Tennessee, 1919) enacted presidential election-only suffrage.

- ↑ Wyoming Territory enacted woman suffrage in 1869; Utah Territory provided for woman suffrage in 1870, the U.S. Congress removed it over the controversy with the Mormon Church and polygamy and it returned with statehood in 1896. Washington Territory passed woman suffrage legislation in 1883 but this was struck down in Territorial Supreme Court decisions in 1887 and 1888. See National American Woman Suffrage Association, Victory: How Women Won It: A Centennial Symposium 1840-1940 New York 1940, pp. 161-166, p. 172.

- ↑ Hunter Graham, Sarah: Woman Suffrage and the New Democracy, New Haven 1996, pp. 99-127, quote p. 99.

- ↑ Hunter Graham, Woman Suffrage and the New Democracy 1996, p. 105.

- ↑ The Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution ratified in 1868 after the American Civil War established a national U.S. citizenship. Thereafter any person born or naturalized in the United States was a citizen of the United States and the federal government had power to protect citizens. But when women tried to vote in the presidential election of 1872 based on the Fourteenth Amendment they were denied, and the U.S. Supreme Court in Minor v. Happersett (1875) found that voting was not one of the “privileges and immunities of citizenship.” Women activists therefore worked state by state to achieve the vote and also to create a constitutional amendment prohibiting discrimination in voting rights by sex.

- ↑ Hunter Graham: Woman Suffrage and the New Democracy 1996, p. 93.

- ↑ York Enstam, Elizabeth: The Dallas Equal Suffrage Association, Political Style, and Popular Culture: Grassroots Strategies of the Woman Suffrage Movement, 1913-1919, in: The Journal of Southern History 68/4 (2002), pp. 817-848.

- ↑ Jensen, Oregon’s Doctor to the World, pp. 120-21.

- ↑ Hunter Graham, Woman Suffrage and the New Democracy 1996, pp. 99-127.

- ↑ See, for example, Lunardini, Christine A.: From Equal Suffrage to Equal Rights. Alice Paul and the National Woman’s Party, 1910-1928, New York 1986.

- ↑ Stevens, Doris: Jailed for Freedom, Salem 1990, reprint of 1920 ed.; Lunardini, From Equal Suffrage to Equal Rights 1986; Cott, Grounding of Modern Feminism 1987, pp. 53-81.

- ↑ Lewis Bredbenner, Candice: A Nationality of Her Own: Women, Marriage and the Law of Citizenship, Berkeley 1998.

Selected Bibliography

- Bristow, Nancy K.: Making men moral. Social engineering during the Great War, New York 1996: New York University Press.

- Brownell, Penelope Noble: The women's committees of the First World War. Women in government, 1917-1919, Providence 2002: Brown University.

- Brown, Nikki L. M: Private politics and public voices. Black women's activism from World War I to the New Deal, Bloomington 2006: Indiana University Press.

- Capozzola, Christopher Joseph Nicodemus: Uncle Sam wants you. World War I and the making of the modern American citizen, Oxford; New York 2008: Oxford University Press.

- Dumenil, Lynn: Women's reform organizations and wartime mobilization in World War I-era Los Angeles, in: The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 10/2, 2011, pp. 213-245.

- Early, Frances H.: A world without war. How U.S. feminists and pacifists resisted World War I, Syracuse 1997: Syracuse University Press.

- Ebbert, Jean / Hall, Marie-Beth: The first, the few, the forgotten. Navy and marine corps women in World War I, Annapolis 2002: Naval Institute Press.

- Enstam, Elizabeth York: The Dallas Equal Suffrage Association, political style, and popular culture. Grassroots strategies of the woman suffrage movement, 1913-1919, in: The Journal of Southern History 68/4, 2002, pp. 817-848.

- Gavin, Lettie: American women in World War I. They also served, Niwot 1997: University Press of Colorado.

- Graham, Sara Hunter: Woman suffrage and the new democracy, New Haven 1996: Yale University Press.

- Greenwald, Maurine Weiner: Women, war, and work. The impact of World War I on women workers in the United States, Westport 1980: Greenwood Press.

- Jensen, Kimberly: Mobilizing Minerva. American women in the First World War, Urbana 2008: University of Illinois Press.

- Jensen, Kimberly: Oregon's doctor to the world. Esther Pohl Lovejoy and a life in activism, Seattle 2012: University of Washington Press.

- Kennedy, Kathleen: Disloyal mothers and scurrilous citizens. Women and subversion during World War I, Bloomington 1999: Indiana University Press.

- Kuhlman, Erika A.: Petticoats and white feathers. Gender conformity, race, the Progressive peace movement, and the debate over war, 1895-1919, Westport 1997: Greenwood Press.

- Lunardini, Christine A: From equal suffrage to equal rights. Alice Paul and the National Woman's Party, 1910-1928, New York 1986: New York University Press.

- Steinson, Barbara J: American women's activism in World War I, New York 1982: Garland Publishing.

- Stimson, Julia C.: The Army Nurse Corps, in: Surgeon-General's Office / Lynch, Charles (eds.): The medical department of the United States Army in the world war, volume 8 part 2, Washington, D.C. 1927: Government Printing Office.

- Weiss, Elaine F: Fruits of victory. The Woman's Land Army of America in the Great War, Washington, D.C. 2008: Potomac Books.

- Zeiger, Susan: In Uncle Sam's service. Women workers with the American Expeditionary Force, 1917-1919, Ithaca 1999: Cornell University Press.