Introduction↑

During the Great War, West Africans were mobilized and conscripted for military service on an unprecedented scale. Europeans relied heavily on conscripted West Africans for the conduct of war in the region. This article will examine how the British and French mobilized and recruited West African soldiers, deploying them for service in the West African campaigns. It illustrates how the heavy deployment of West Africans was key to the outcome of the campaign in the region. The focus will be on the two campaigns of Togo and Cameroon. In discussing the latter, the German military conscription of Cameroonians is examined, as well as recruitment efforts by the Allies. The article ends by discussing the impact of mobilization and recruitment on the region.

Mobilization, Conscription and Deployment of British and French West Africans↑

West Africa was an important arena in World War I. Two German West African colonies, Togo and Cameroon, became targets for Allied military onslaughts. The German economic and material transformation of Togo made it a desirable asset for the Allies. For strategic reasons, and perhaps by far the most important, the Allies desired to cut off German communications by seizing the powerful transmission stations in Togo and Cameroon. Seizing these stations frustrated German naval operations while helping the Allies; it was an act that was crucial for the global outcome of war.[1] France in particular had imperial scores to settle with Germany over West African territories. Taking Togo and Cameroon thus became part of settling those scores. Even Great Britain had not forgiven Germany for going behind its back to annex Cameroon in 1884. Thus, at the outbreak of war, German attempts and diplomatic efforts to deter the Allies from extending confrontations to Africa came to naught. These British and French imperial aims, according to historian Brian Digre, gave Britain and France the chance to repartition Africa. Finally, the Allies were convinced that conquering and depriving Germany of its West African territories would damage Germany's morale and cut it off from vital supplies necessary for the conduct of war. Against this backdrop West Africa became one of the early theatres of confrontation in WWI. But how would war in those two German West African colonies, both sandwiched between British and French colonies, be fought and won? For very practical reasons this required mobilization, recruitment and the use of British and French West Africans.

British West Africa↑

British West African colonies included Nigeria, Ghana, Sierra Leone and the Gambia. Soldiers from these colonies served in two military formations: the West African Regiment in Sierra Leone and the West African Frontier Force (WAFF). These forces were led exclusively by British officers.[2] Whereas the West African Regiment was part of a regular army administered by the War Office, the WAFF was controlled by the Colonial Office. The WAFF was raised chiefly from the Hausa groups of the west coast, judged by the British to be a "warlike Mahommedan race not purely negroid."[3] In 1914, the WAFF numbered over 8,000 soldiers, mainly Africans, with fewer than 400 British. Nigerians in the force alone numbered over 5,000.[4] As existing British West African forces were insufficient, Britain soon began to recruit more men. In the Gold Coast, Britain mainly recruited from peoples of the northern territories and from neighboring French territories. This recruitment occurred largely via compulsion, with the complicity of chiefs acting on the orders of the recruiting officers. Although Britain's declared policy had been to recruit only volunteers, colonial officials inevitably turned to forcing the chiefs to supply soldiers when the need for reinforcements became acute.

Gold Coast West Africans resisted recruitment efforts. In the Central and Western Provinces, recruitment efforts largely failed, as potential recruits fled into the bush. Besides their reluctance to be sent to faraway places to fight, cocoa farming was a more attractive occupation. Desperate in their recruitment efforts, British officials often threatened the chiefs to meet quotas. They even accelerated marriages in order to secure the young men's enlistments. "Every man, who wanted an unmarried girl who wanted him, was assured of a favourable decision before the Commissioner even if the girl's father was reluctant to part with her."[5] Still, recruitment targets were not met. Many chiefs refused to cooperate and many recruits deserted.

In Nigeria, British recruitment policies were similar. By September 1918, 17,000 Nigerian combatants had participated in the Cameroon and East African campaigns. Over 4,000 Nigerian troops also served along Nigeria's borders with Cameroon and inside Nigeria itself.[6] Although British policy before the war had been to recruit volunteers, this changed dramatically during the war, so that although Britain did not adopt a formal policy of conscription in West Africa, as did France, it coerced large numbers of Nigerians into military service. In Nigeria the British relied mainly on traditional rulers for recruits. In some cases, this worked particularly well, since some rulers took advantage of the situation to supply recruits in return for political gains. The Emir of Yola, wanting to gain control of territory that extended to German north Cameroon, provided soldiers who assisted in the British attacks on Garoua (Cameroon) in 1914/15. However, the majority of rulers who complied with recruitment demands did so under duress. Rulers in and around Zungeru and along the Cross River flatly refused to comply, including many in Yoruba land and south-western Nigeria.[7]

On the whole, for services in West Africa and beyond, the various regiments of the British WAFF provided about 70,000 men. Nigeria provided the most, followed by the Gold Coast.[8] Although many British West Africans volunteered, many more were coerced, often through the intermediation of traditional authorities. Such recruitment methods often caused high rates of desertion.[9]

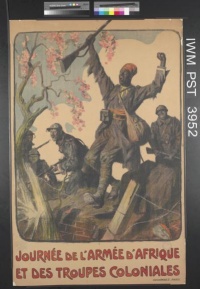

French West Africa↑

France recruited 178,000 men in the region during the war, in addition to the 31,000 under arms in 1914. About 135,000 served overseas, with over 30,000 killed. Recruitment often provoked flight. Many inhabitants in Guinea, Ivory Coast and Dahomey fled to neighboring British colonies.

Coercion was an integral part of French methods, often channeled through colonial administrators and African intermediaries. Unorthodox and punitive methods were employed, with colonial officials often imprisoning uncooperative chiefs and taking the parents or other relatives of potential recruits hostage. Villages which refused to comply risked having their crops and livestock destroyed by the colonial government. However, monetary incentives were also given to chiefs and recruitment agents for meeting recruitment targets. By 1914, Europeans in West Africa had identified men from certain areas as warlike and suitable for combat. In Senegal, for instance, these were mostly the people of the interior. Over 90 percent of West Africans recruited in Senegal during the war were from the so-called warlike races.

France's great losses in the early days of the war intensified recruitment, so that from August 1914 to October 1915 over 32,000 more West Africans were recruited. General Charles Mangin (1866-1925), the chief advocate of recruiting West Africans, told the French Minister of War in August 1915 that France could raise 300,000 more recruits from West Africa. In October 1915 the French government decreed that the colonial administration provide 50,000 new soldiers.[10]

Recruitment of French West Africans was haphazard. Recruits received insufficient training, leading to a high mortality rate. Men who had come seeking work on the docks of Dakar were simply conscripted.[11] France launched a successful drive for recruitment in 1918 under the African deputy, Blaise Diagne (1872-1934). Commissioned by Georges Clemenceau (1841-1929) to lead the drive for recruitment in the AOF, and aided by new incentives and new persuasive methods of recruitment, Diagne and the colonial administration enlisted 63,000 new recruits for the French army by the end of August 1918.[12] Recruits were deployed in Togo and Cameroon.

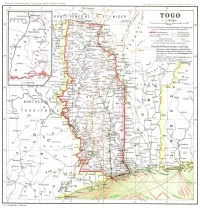

The Togo Campaign↑

After recruiting and mobilizing African troops, Britain prepared to invade Togo, targeting the transmission station at Kamina. The French followed suit, but with the intent of gaining more West African territories.[13] Nevertheless, the Allies agreed on a joint military action.

The Gold Coast Regiment of the WAFF led the attack on Togo. This infantry Regiment had fewer than fifty Britons but more than 1,500 Africans.[14] France engaged 1,300 well-trained West Africans. Pitted against over 5,000 Allied troops was a German militarized police force of barely 1,200 Africans. In addition to this numerical imbalance, the Allies had far superior and more modern weapons. Predictably, the Allied operations quickly proved successful, lasting only two-three weeks. By 6 August 1914, French West African police had already crossed into Togo. The town of Lome quickly surrendered to the British.

Beginning on 9 August, the French recruited 500 Togolese chieftains and over 600 of their people as auxiliary cavalry, together with fifty-six police with whom they advanced on the north-eastern part of Togo, clearing the way for a company of tirailleurs to advance in cooperation with the British Gold Coast troops.[15] From Lome, the British advanced on Kamina with a large number of local recruits but encountered considerable German resistance.[16] At a railway bridge at Togblekove on 12 August 1914, Gold Coast born Sergeant-Major Alhaji Grunshi fired the first shot by a soldier of a British unit in World War I. The Allies then pursued German forces further inland, engaging a German force at the Battle of Khra around 23/24 August. The German West African troops, who had dug trenches and prepared for war, dealt a severe blow to the Allied West African troops.[17]

Although the Germans were quite successful at Khra, their lack of local support soon forced them to retreat. By 25 August the Germans unconditionally surrendered Togo to the Anglo-French force.[18] On 28 August, British and French officials concluded a partition arrangement. The Gold Coast British administration, reluctant to add a "worthless and costly" African colony to the British West African possessions, chose to only gain the western districts of Togo, leaving the eastern districts (60 percent) and Kamina to France.[19]

The Togo campaign validates the importance of West Africans and the role that the lack of local support for the Germans played in the Allied victory. During the campaign, the Allied African troops gave a good account of themselves. At the same time, the consequence was the hostility of large numbers of Africans towards the Germans.[20] The West African soldiers in the German force frequently deserted to join the Allies, thereby frustrating German war efforts. At one point, 180 German Togolese soldiers surrendered to the British with their weapons.[21] The frequent desertion by African soldiers from the German to the Allied camp has eluded the attention of historians as an important aspect of the German defeat and Allied victory in African campaigns of the war.

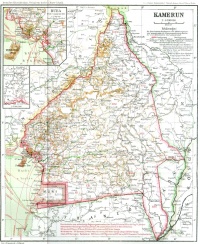

The Cameroon Campaign↑

Once the Allies decided to invade German Cameroon, both they and the Germans faced certain military realities that necessitated the recruitment and use of locals. Therefore, to fully appraise the background of Allied and German military conscription in the campaign, it will be necessary to firstly discuss the military difficulties that impeded military operations in the territory.

The Allies were unfamiliar with the bush and forest terrain. Moreover, the Cameroon climate was "probably very nearly the worst in West Africa."[22] Other difficulties included an absence of roads, rivers without bridges and often without fords, swamps that made artillery fire impossible, violent and aggressive animals, prolonged marches, and a recurrent shortage of supplies.[23] However, the Allies possessed a numerical superiority over the Germans and had a superb spying system facilitated by local cooperators. They obtained Cameroonian recruits who had a better knowledge of the terrain and knew how to conduct warfare on their own territory.

For the Germans, their greatest military impediment was a lack of munitions, artillery and shortage of men. Additionally, the Germans complained of a wide-spread system of espionage, which they said the British carried out even before the commencement of war, partly through English officers who happened to be making pleasure trips through the Cameroons, and partly through English merchants who, according to a German non-commissioned officer, "sent bribes to the natives even just before the war." However, the Germans possessed a far better knowledge of the terrain and had adapted local military strategies necessary for warfare in the Cameroons. In any case, given the various difficulties for the European belligerents, reliance on Cameroonian recruits and local strategies became urgent.

German Wartime Military Conscription↑

Prior to the outbreak of confrontations, the German force in Cameroon comprised only 1,550 Africans and 185 Germans.[24] In total, the Germans would recruit over 90 percent of their Cameroonian soldiers during the war.

As the Allies prepared to invade Cameroon, Governor Karl Ebermaier (1862-1943) found himself in a quandary. He had inherited an aggrieved population, caused by German colonial brutality. Seeking to make amends, Ebermaier made a somewhat belated concession on the flogging of Cameroonians, and issued a declaration that was presumably regarded as a magnanimous and liberal piece of policy and a volte-face. The declaration, promising to abolish corporal punishment and to reward Cameroonians who remained faithful to the German cause also threatened severe punishment to subversives.[25] With such carrots and sticks, the Germans began to search for wartime conscripts. Recruits were drawn continuously from the Beti area in Yaounde, whose chief, Charles Atangana (1880-1943), remained 'loyal' to the Germans throughout the war.[26] Following Ebermaier's declaration, the German North Cameroon resident, Hauptmann Karl von Crailsheim (1880-1947), solicited the aid of the Muslim leaders of Garoua.[27] Attempting to invoke religious sentiments, the Germans circulated letters amongst the northern Muslim community claiming that this was a religious war pitting Christianity against Islam, with they (the Germans) fighting for the cause of Islam.[28]

Previously, German religious propaganda had begun to make gains. As early as August-September 1914, the Lamido of Garoua provided hundreds of warriors armed with rifles.[29] Successful German conscription in the north, coupled with the intensive military build-up at Garoua, posed a real challenge to the Allies and protracted the war there until 10 June 1915, when a confluence of British and French forces forced them to surrender the town. Additionally, in August 1914 the Germans in the Mandara region recruited about 135 local fighters, in addition to those that had been conscripted prior to the war. These recruits, together with about 200 other local soldiers and a few German officers, held back Allied attacks in Mora until February 1916.[30]

Further down in the Bamenda western grasslands of the North West, German recruiters utilized strong rulers to find recruits. Some of these rulers quickly picked their undesirable subjects, suddenly making recruitment a form of punishment. The traditional leader of the Kom ethnic grouping, Fon (or King) Ngam, provided the Germans with more than 500 men, most of whom were new Christian converts who had become rebellious against traditional authority.[31]

The Germans set up wartime training centers, offering limited training to the new recruits, who thus had to have their own skills. From February-March 1915, the Germans in the grassland area spent time training recruits at the military station in Bamenda. Earlier, further up in the north, the Germans had established a training center at Banyo. When war broke out, the Germans in Banyo quickly conscripted 100 Cameroonians from the Banyo training center and used them to hold Banyo from being captured by the numerically superior Allied troops until 24 October 1915.[32]

Recruits also brought their personal military experiences and expertise; in addition to fighting, they constructed fortifications in the forests and dug trenches – both aspects typical of warfare in Cameroon. In Bakumba, a mountainous and thickly forested place in the Cameroon-Nigeria Cross River area, recruits cleared a distance of one kilometer around the village, after which they turned the village into a fortified position by erecting cover, building timber fortifications, and digging trenches.

As the war progressed, the Germans found ways of wooing Cameroonians into military conscription. At one point in the Edea region between Douala and Yaounde, the Germans bribed potential recruits and retained new ones by offering them rewards such as slaves, the right to pillage, and a free hand to rape seized women.[33] The practice of Europeans offering seized women to their African soldiers, or condoning and promoting African male sexual violence against African women as a payoff for military services in the colonial army was not new.[34]

Terrified by German wartime conscription, General Charles Macpherson Dobell (1869-1954), Commander in Chief of British actions in West Africa, panicked in April 1915 that German African new recruits constituted "an addition to the hostile fighting strength" of the Germans.[35] In January 1915, the Commander-in-Chief of French troops in West Africa had expressed concern over the German mobilization and recruitment of locals as a factor for protracting the campaign in the territory.[36]

Allied Wartime Military Recruitment↑

In September 1914, a joint Anglo-French force of 12,000 men invaded German Cameroon. This force comprised mainly West Africans from different Allied West African colonies and a few from the Belgian Congo. Other British and French forces from neighboring colonies separately invaded other parts of Cameroon.[37] Although these Allied troops entered Cameroon with a general policy not to recruit from the local populace, they soon realized that local recruits were indispensable, particularly for logistic functions, garrisoning, and for helping to navigate unfamiliar terrain. In April 1915, British naval officers at Dipikar began to inspect thirty Cameroonian levies composed of Kribis and Pangwes and armed with French and British obsolete rifles. These levies were made to guard Allied blockhouse defenses in the area in case of a German attack. It is not reported whether these levies received any European military training, but it is unlikely that they did. These small levies denied the Germans the use of the road to Ayamekem from the interior and served as a shield for Allied troops at Ayamekem, who were then able to launch successful attacks on the Germans. At the neighboring Campo village, twenty other levies were garrisoned at a camp that contained 200 refugees displaced by the Germans. In addition to their guard role, the levies carried out rifle training with ammunition supplied by the British Royal Navy.[38]

Cameroonian soldiers deserting the German camp, as well as those captured, were sometimes incorporated into the Allied force. This British practice of re-recruiting African deserters from the German army would be repeated, as occurred in 1918 during the East African campaign, when the British recruited almost an entire battalion of prisoners and deserters from the German Defense Force, to take up combat roles against the same Germans.[39]

The Allies also drew recruits from the pool of wartime refugees, especially those displaced from their homes by the advancing German soldiers. At one point in January/February 1915, about 4,000 German displaced Cameroonian refugees converged at Allied outposts in Edea, 2,000 or more at Kribi, a large number at the Nyong River entrance and another large number at Campo. The British took advantage of the situation so that while protecting the refugees, they recruited and armed a handful to repel the advancing Germans.[40]

The recruitment and engagement of Cameroonians in the Cameroon campaign was a decisive factor in that campaign. The peculiarity of the terrain made the use of local fighters especially important. Even European military officers were compelled to borrow and adapt skills and tactics applicable to local topography. Indeed, the nature of Cameroon forced a British Colonel to "adopt a system of tactics applicable both to bush and mountain warfare."[41] The effectiveness of Africans in the campaign cannot be overstated.

On the whole, the Allies, with a huge numerical advantage of West African and Cameroonian soldiers over the Germans, were able to defeat the Germans by February 1916. Beginning on 27 September 1914, the Allies seized the important coastal town of Douala and the Germans moved further inland. Battle after battle ensued, and with massive support from local recruits, town after town fell to the Allies, despite strong German resistance. By January 1916, British and French West African forces closed on the Germans in Yaounde, forcing Governor Ebermaier and his remaining German soldiers and subjects to surrender Cameroon and exit to Rio Muni through the South. Britain and France then divided Cameroon. As had happened in Togo, Britain gave France most of Cameroon, as it did not want to add more "worthless" territory, instead exchanging it for African territories elsewhere.

The Impact of European Military Recruitment on West Africa↑

Because of European needs for reinforcements, the entire West African region became increasingly militarized. In Nigeria, the need for reinforcements turned attention away from the Hausa and Yoruba, who in the first decade of the century had constituted over 80 percent of the colonial military force. Colonial officials now turned to "pagan groups" in south-eastern Nigeria, particularly the Ibos, so that by 1916, the Hausa and the Yoruba constituted less than 50 percent of new recruits.[42]

Unprecedented mobilization of West Africans adversely affected the region's internal labor markets.[43] Although the contribution of British West Africa was much smaller than that of British East Africa, it represented the largest and most sustained program of recruitment in West African history. The Gold Coast alone provided 16.7 percent of the nearly 70,000 British West African soldiers in the war.[44] Because of the mobilization and recruitment campaigns, however, the Nigerian economy suffered as locals rebelled against recruitment and deserted. Laborers involved in road and railway construction deserted en masse for fear of conscription. The military practice of impressing commercial laborers also disrupted industrial and agricultural production.[45] Young men and women who should have been working in the farms were seized. Recruitment also greatly affected the Gold Coast’s economy. While fear of conscription interfered with the free flow of labor and farming activities, N.A. Cox-George thinks that there is little evidence to support the contention that recruitment "depleted" the able-bodied and skilled in the ranks of the agricultural labor force.[46] However, military recruitment in the Gold Coast posed a serious threat to the mining industry. Since most of the labor force in this sector had come from the traditional northern areas for recruitment, labor forces fell during the war from a total of 17,400 in 1914 to 10,800 in 1918.[47]

Conscription of West Africans rekindled raids that had been typical of the slave trade era. The methods of forced recruitment, such as raids conducted by African recruiting agents to capture and imprison young men before presenting them as "volunteers," were "clearly reminiscent of the slave trade, despite the fact that the eradication of slavery was supposedly one of the proudest achievements" of the colonizers.[48]

Harsh military conscription policies, especially in the French West African colonies, destabilized local populations and caused refugee problems. By 1918, between 15,000 and 18,000 immigrants from French neighboring territories had entered the Gold Coast. Some were enlisted by the British, but most were employed in mines and on roads.[49] In the Cameroons, conscription by the Germans caused serious problems. As German recruiters combed villagers for young men, villagers often ran to Allied camps for protection while others fled into the bush. Consequently, a refugee problem ensued. Many refugees ended up in plantation camps, either in Cameroon or in neighboring countries.[50]

Recruitment and conscription attempts sometimes led to organized resistance against the Europeans; European attempts to end such resistance caused the loss of more African lives. In 1915, 200 Ibo (Nigeria) lives were lost as the government brutally suppressed resistance to recruitment. In northern Nigeria, wartime recruitment also contributed to violence, when as many as 200 rebels and three dozen unarmed men and women - including many Baloguns – were killed by colonial officials to quell the resistance.[51] Generally, resistance and violence was less intense in British than in French West Africa. According to David Killingray,

Roger Thomas sees this as an oversimplification, and demonstrates that as the war progressed and the need for reinforcements became urgent, the British Gold Coast government frequently carried out a de facto conscription policy that caused a great deal of resistance and violence.[53]

Conclusion↑

In the West African campaign of WWI, West African soldiers sacrificed themselves on battlefields. This enabled the Allies to score their first victory of the war in Togo and to proceed to win in Cameroon. Although some West Africans fought for Germany, the vast majority fought on the side of the Allies and played an integral part in the Allied victory. There is still much to learn about the West African campaigns of the war. The pattern for historians writing on the African campaigns has been to adopt a social-labor history approach that largely views African soldiers in the war as appendages of the colonial state. This approach is insufficient to understand the Cameroon West African campaign, in which over 90 percent of Cameroonians fighting for either the Germans or the Allies were recruited during wartime and began fighting without any European training. They possessed military skills and experiences of their own which they used to conduct the war, in the course of which they forced the European belligerents to conduct the war on their own terms. That Cameroonian soldiers brought their personal experiences to bear on the war is one powerful piece of evidence for the importance of Africa to the history of the First World War and for the importance of the war to the history of Africa.

George N. Njung, Baylor University

Section Editors: Melvin E. Page; Richard Fogarty

Notes

- ↑ British National Archives (hereafter referred to as BNA), ADM 186/607, p. 158.

- ↑ BNA, ADM 186/607, "Naval Staff Monographs, Vol. 2", pp. 157-158.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 158.

- ↑ Farwell, Byron: The Great War in Africa, 1914-1918, New York London 1986, pp. 35-36.

- ↑ Killingray, David: Military and Labour Policies in the Gold Coast during the First World War, in Page, Melvin E. (ed.): Africa and the First World War, New York 1987, p. 161.

- ↑ Matthews, James K.: Reluctant Allies: Nigerian Responses to Military Recruitment 1918, in Page, Melvin E. (ed.): Africa and the First World War, New York 1987, p. 95.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 96-9.

- ↑ Killingray, Repercussions 1987, p.46.

- ↑ Barret, John: The Rank and File of the Colonial Army in Nigeria, 1914-18, in The Journal of Modern African Studies, 15/1 (1977), p. 112.

- ↑ Fogarty, Richard S.: Race and War in France: Colonial Subjects in the French Army, 1914-1918, Baltimore 2008, pp. 27-30.

- ↑ Page, Melvin E.: Introduction: Black men in a White Man's War, in Page (ed.), Africa and the First World War 1987, p. 4.

- ↑ Fogarty, Race and War 2008, pp. 50-51.

- ↑ Grove, Eric J.: The First Shots of the Great War: The Anglo-French Conquest of Togo, 1914, in The Army Quarterly and Defence Journal, 106 (1976), p. 309.

- ↑ Report on the Gold Coast Volunteers for 1913, BNA, CO 96/546.

- ↑ Grove, The First Shots 1976, pp. 313-14.

- ↑ Naval Operations in the Cameroons, 1914, BNA, ADM 186/607, p. 159.

- ↑ Moberly, F.J. (Brig.-General): History of the Great War Based on Official Documents: Military Operations, Togoland and the Cameroons, 1914-1916, London 1931, p. 319.

- ↑ Naval Monographs; The Inception of the Cameroons Expeditionary and Preliminary Movements, The Togoland Expedition 1914, BNA, ADM 186/607, p. 59.

- ↑ Moberly, Military Operations 1931, pp. 40-41.

- ↑ Grove, The First Shots 1976, p. 322.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 322-323.

- ↑ Major General Charles Dobell, Factors affecting Military Operations in the Cameroons, BNA, ADM 137/224 p. 267.

- ↑ Bond, Edward: The Conquest of the Cameroon, in The Contemporary Review, 109 (January 1916), p. 620.

- ↑ Naval Operations in the Cameroons, 1914, BNA, ADM 186/607, p. 158.

- ↑ BNA, CO 879/117, p. 49.

- ↑ For the 'loyalty' of the Beti of Cameroon to the Germans throughout the war, see Quinn, Frederick: The Impact of the First World and its Aftermath on the Beti of Cameroun, in Page (ed.), Africa and the First World War 1987, pp. 171-185.

- ↑ Barkindo, Bawuro M.: The Mandara Astride the Nigeria-Cameroon Boundary, in Asiwaju A.I. (ed): Partitioned Africans: Ethnic Relations Across Africa's International Boundaries 1884-1984, London 1985, p. 36.

- ↑ Stoecker, Helmut: Loyalty to Germany in Cameroon 1914-1930 in Ndumbe, Kum'a III (ed.): Africa and Germany from Colonisation to Cooperation 1884-1986 (The Case of Cameroon), Yaounde 1986, p. 332.

- ↑ Eyong Tabe, Kennedy: Kamerunian Participation in the First World War, 1914-1916, University of Buea-Cameroon MA Thesis, Buea, 2001, p. 107.

- ↑ "Annual report General File," Ba 1919 (1), File # 53/1920, Cameroon National Archives, Buea (hereafter referred to as CNAB).

- ↑ See de Vries, Jacqueline: Catholic Mission. Colonial Government and Indigenous Response in Kom (Cameroon), Leiden 1998, p. 34.

- ↑ BNA, ADM 137/339, p. 351.

- ↑ Fuller (British Senior Naval Officer), Report on naval and military operations in Kribi and Edea, Great Batanga and the Nyong, Campo, Garua, Dschang, Ekok, Harman's Farm, BNA, ADM 137/224, p. 16.

- ↑ See, for example, Moyd, Michelle: "'All people were Barbarians to the Askari': Askari Identity and Honor in the Maji Maji War, 1905-1907." in Giblin, James and Monson James (eds.): Maji Maji. Lifting the Fog of War, Leiden 2010, pp. 149-179.

- ↑ BNA, ADM 137/224, p. 264.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 454.

- ↑ Clarke, West Africans, p. 11.

- ↑ BNA, ADM 137/224, pp. 550-551.

- ↑ Iliffe, John: Honour in African History, Cambridge 2005, p. 230.

- ↑ Fuller, Report on naval and military operations, p. 16.

- ↑ Dobell, Report on Military Operations, p. 197.

- ↑ Barret, John: The Rank and File of the Colonial Army in Nigeria, 1914-18, in The Journal of Modern African Studies, 15/1 (1977), pp. 106-107.

- ↑ Killingray, Military and Labour Policies 1987, p. 152.

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Matthews, Reluctant Allies 1987, p. 109.

- ↑ Cox-George, N.A.: Studies in Finance and Development. The Gold Coast (Ghana) Experience 1914-1918, in Public Finance, 13 (1958), p. 155.

- ↑ Killingray, Military and Labour Policies 1987, p. 163.

- ↑ Fogarty, Race and War 2008, p. 30.

- ↑ Killingray, Military and Labour Policies 1987, p. 164.

- ↑ Sundiata, Ibrahim K.: From Slavery to Neoslavery. The Bight of Biafra and Fernando Po in the Era of Abolition, 1827-1930, Madison 1996, p. 125.

- ↑ Mathews, Reluctant Allies 1987, pp. 102-103.

- ↑ Killingray, Military and Labour Policies 1987, p. 163.

- ↑ Thomas, Roger: Military Recruitment in the Gold Coast during the First World War, in Cahiers d'Études Africaines, XV/57 (1975), pp. 57-58.

Selected Bibliography

- Barrett, John: The rank and file of the colonial army in Nigeria, 1914-18, in: The Journal of Modern African Studies 15/1, 1977, pp. 105-115.

- Clarke, Peter B.: West Africans at war, 1914-18, 1939-45. Colonial propaganda and its cultural aftermath, London 1986: Ethnographica.

- Farwell, Byron: The Great War in Africa, 1914-1918, New York 1986: Norton.

- Fogarty, Richard: Race and war in France. Colonial subjects in the French army, 1914-1918, Baltimore 2008: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Gorges, Edmund Howard: The Great War in West Africa, London 1930: Hutchinson & Co.

- Grove, Eric J.: The first shots of the Great War. The Anglo-French conquest of Togo, 1914, in: The Army Quarterly and Defence Journal 106, 1976, pp. 308-323.

- Killingray, David: Military and labour policies in the Gold Coast during the First World War, in: Page, Melvin E. (ed.): Africa and the First World War, New York 1987: St. Martin's Press, pp. 152-170.

- Matthews, James K.: Reluctant allies. Nigerian responses to military recruitment 1914-18, in: Page, Melvin E. (ed.): Africa and the First World War, New York 1987: St. Martin's Press, pp. 95-114.

- Moberly, F. J.: Military operations. Togoland and the Cameroons, 1914-1916, London 1931: His Majesty's Stationery Office.

- Page, Melvin E. (ed.): Africa and the First World War, New York 1987: St. Martin's Press.

- Quinn, Frederick: The impact of the First World and its aftermath on the Beti of Cameroun, in: Page, Melvin E. (ed.): Africa and the First World War, New York 1987: St. Martin's Press, pp. 171-185.

- Strachan, Hew: The First World War in Africa, Oxford; New York 2004: Oxford University Press.