The War of Others↑

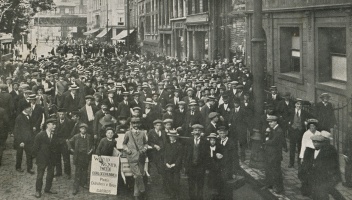

The week before the outbreak of the war was a nervous one, even in the Netherlands. In Germany and the United Kingdom, the declaration of war meant the end of uncertainty and clearly marked a new phase. In the neutral Netherlands, the declaration of general mobilisation on 31 July had a comparable effect. People gathered in the streets, looking for news and company. In a couple of days some 200,000 men, a vast amount of military equipment and ammunition, vehicles and horses were transported – mostly by train – to their destination.

People were excited, worried, and nervous, but it seems that they were generally calm, at least in public space, and they were exhorted and exhorted each other to remain calm. Patriotic enthusiasm was considered undesirable, though war enthusiasm also inspired Dutch artists, scientists, and intellectuals in the summer of 1914. Like their counterparts in belligerent countries, some of them welcomed the war which they expected would have a regenerative effect on society.[1] Another group of intellectuals that would gain momentum during and after the war opposed the dehumanising character of the war and argued for a spiritual revolution. Marjet Brolsma has qualified them aptly as “humanitarian idealists”.[2] This article will focus on popular reactions to the war, distinguishing between different segments of the population as far as available research allows. It will discuss if and to what extent the Dutch considered the First World War a war of others, both during and after the conflict.

Public debate in contemporary journals was not so much characterized by war enthusiasm but, as Ismee Tames has argued, should be considered a manifestation of a specific form of cultural mobilisation. It was not initiated and stimulated by the state, but was primarily bottom-up. In the Dutch case the aim of the mobilisation was not support of the war, but neutrality.[3] Public opinion leaders discussed the origins of the war, but also the position, role, and identity of the country.

The outbreak of the war, especially the German invasion of neutral Belgium, was a profound shock for Dutch faith in international law. In the first few months the value of international law would be an important theme in public debate. Besides, public opinion leaders were preoccupied with the numerous writings from famous German scientists and intellectuals, rejecting Germany’s responsibility for the outbreak of the war. In early 1915 the contemporary historian and commentator G.W. Kernkamp qualified this as the “disease” of the German scholars.[4]

Meanwhile, the arrival of refugees, especially in October 1914, made it clear that neutrality did not automatically mean that Dutch society would be entirely protected from the consequences of the war. Dutch citizens, keen to have a non-military but active role in the international conflict, enthusiastically embraced the opportunity to provide aid to the refugees. A second non-military role was that of unofficial “observer”, urging the belligerents to uphold international law. Especially in 1914 several Dutch journalists who reported from the battle zone in Western Europe in 1914, acted as critical commentators. One of them was Lambertus Mokveld (1890-1968), who intervened and complained with German authorities. His book about the alleged myth of franc-tireurs appeared in English in 1917 as The German Fury in Belgium. This publication made Mokveld an important player in the propaganda war between Germany and the Entente.

War and Peace↑

Prior to 1914 the Netherlands was a small state whose citizens relied on neutrality to keep them out of a potential future war. Neutrality was primarily considered essential for the country’s independence and for overseas trade; but, in the course of the 19th century, the concept of neutrality was increasingly seen as an aspect of Dutch identity. Military aspirations were not part of the self-image, which was reinforced and emphasized with the two Peace Conferences in The Hague in 1899 and 1907. However, the Third Peace Conference, planned for 1914 and later postponed to 1915, did not materialize. Although the outbreak of the war was a blow for the peace movement, it proved remarkably resilient. Within weeks of the opening of the hostilities, a new anti-war organization was established which aimed to unite the different pacifist movements. The Dutch Anti-War Council (Nederlandsche Anti-Oorlogsraad, NAOR) built on the ideals of the earlier peace conferences by focusing on international cooperation, arms control, and arbitration.

Initially the NAOR was rather successful in mobilising support predominantly in middle and higher-class circles. By July 1915 one thousand organisations had joined the NAOR. This added up to some 30,000 individuals organised in 150 local groups throughout the country. In the course of the war, however, when the immediate threat of hostilities crossing the Dutch border had subsided, the growth of the NAOR halted.[5]

The NAOR did not succeed in attracting socialist groups or individual workers and farmers. The Social Democratic Workers’ Party (SDAP) was divided on the issue of pacifism. The right wing supported the views of the NAOR, whereas for the left wing NAOR’s pacifism was not radical enough. The SDAP did not join the NAOR and officially rejected abolition of the army. Instead, it wanted to transform the existing professional army into a people’s army including general conscription for men. The party’s support for the liberal government’s policy to safeguard neutrality meant that it also supported the mobilisation. For ideological reasons – one had to be able to wage a potential class war – the SDAP did not embrace the principle of non-violence.[6]

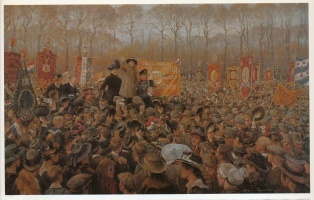

Revolutionary socialists, syndicalists and anarchists were more radically pacifist, and as such against the idea of a people’s army. They considered the mobilisation an undesirable militarisation of society. Their demonstrations attracted substantial audiences. In the spring of 1915 authorities intervened in the political work of revolutionary socialists. They banned revolutionary dailies and disbanded independent mobilisation groups.[7]

In June 1915 discussions in parliament about an extension of the conscription law (Landstormwet) reinvigorated antimilitarist activism. In September the first edition of the manifesto for refusal of military service, drafted by the Christian Socialist Bart de Ligt (1883-1938), was circulated. Refusing military service became one of the focal although controversial and not successful points of the antimilitarist agitation of the revolutionary left. Although keeping some 200,000 men in active duty meant a strain on the army itself, on state resources, infrastructure, economy, and family life, the vast majority of the population considered the mobilisation useful to keep the country out of the war. Instead of supporting the antimilitarist agitation for a general demobilisation, they argued for a partial demobilisation.[8] In a country that had given itself a special mission to bring peace into the world, activism for peace and peaceful ends manifested itself during the war years in new forms across the political spectrum. However, none of the groups succeeded in mobilising broad support.

Pro- or anti-German↑

For most Dutch, reflecting on the war entailed reflecting on the activities of the belligerents. Most importantly, from their perspective, was an understanding that to be “neutral” during the war involved being careful with their opinions. As a result, the question of whether a position was inherently pro or anti-German dominated many public discussions. Discussions often focused on propaganda and especially on alleged Dutch contributions to German propaganda. Both neighbouring belligerents were actively trying to influence Dutch public opinion. The British approach and communications were much more similar to the Dutch discourse with a focus on law, civilization, reason, and other liberal moral values. As a result, it soon became difficult for Dutch opinion-leaders to define national – and neutral – identity by using the concepts used by one of the main belligerents.[9]

In 1915 developments in the war marked the beginning of a new phase. In particular, the escalation of the war at sea had a large and lasting impact on public opinion in the Netherlands. The Dutch began to consider themselves victims of the war. During the entire conflict, nothing would infuriate the Dutch more than the aggression and obstruction of the freedom of movement at sea. Attacks on neutral ships went straight to the heart of the maritime Netherlands.

The dominant emotion in response to these attacks was anger combined with a sense of powerlessness and humiliation. The attacks were perceived as a violation of international law and discussed in terms of murder.[10] In May 1915 the German attack on the British passenger vessel Lusitania elicited fierce responses. The openly pro-German agitation of the journal De Toekomst was strongly criticized. As Tames and others have shown, the journal was accused of being an instrument in the German propaganda efforts.[11] J.A. van Hamel (1880-1964), professor of criminal law and editor of a liberal weekly, increasingly exposed the pro-German activity of the journal and thus mobilised a substantial number of intellectuals who were also worried about German influence on the Netherlands. Van Hamel warned that the German scientific influence was the deliberate first step towards political annexation. In public debate, the focus shifted from law and justice to national independence.[12]

The Small Nation↑

The emphasis on the nation and on alleged national characteristics led to a number of attempts to mediate between the belligerents. A well-known example is the attempt of the Dutch writer, psychiatrist, and utopian socialist Frederik van Eeden (1860-1932) who, as one of the humanitarian idealists, was motivated to provide moral guidance to intellectuals in the belligerent countries. In late 1916/early 1917 he met with the German envoy in The Hague and had a meeting in London with the British prime minister in an attempt to bring about a peace conference between the main belligerents. Van Eeden’s attempts remained without result.[13] Others attempted to mediate as well, including foreign minister John Loudon (1866-1955) and prominent businessman Anton Kröller (1862-1941). From 1917 on, the NAOR Board focused on international relations and activities. They were involved in several mediation attempts, which seem not to have been very successful.

Powerlessness regarding the war in general and the war at sea with its violations of international law in particular, was frustrating and made many people extremely angry. It confronted the country with its status as a small power. As the war progressed, the public mood became increasingly depressed. An all-time low was reached in late February 1917, when German submarines torpedoed seven Dutch grain ships. The country felt squeezed between the belligerents and there was little one could do, except filing diplomatic protests against violations of neutrality and international law. That these protests were not very successful added to the sense of despair. The anger, frustration, and hurt pride made some people nostalgic for the 17th century, when the Netherlands was one of the major powers the world had to reckon with. This nostalgia demonstrates that it could no longer be denied that the country was not in the position to change the course of events. The only thing one could do was wait for the war to end.[14]

The War as a Spectacle↑

As a generalisation, it seems justified to state that the majority of the Dutch was neither antimilitarist nor pacifist. They were not easily attracted to military matters and military aspirations. There was a consensus that the armed forces were necessary for self-defence, but nothing more than that. However, new scholarship gives enough reason to nuance these statements. The military historian Wim Klinkert for instance has argued convincingly for a more realistic (self-)image of the Netherlands which does justice to its military tradition and experience. In this context, Klinkert highlights the temporary militarisation of society and preparation for war.[15] Additionally, Conny Kristel has demonstrated that there was a widespread curiosity for the way the war was being fought.[16]

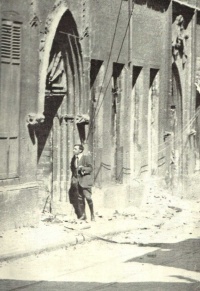

In the early days of the war, citizens in the southern part of the country were keen to watch the military operations, equipment, and logistics from the hills south of the city of Maastricht. People were aghast, but also fascinated. Some of them even audaciously crossed the border to see the hostilities with their own eyes and to speak with both Belgian and German soldiers. Especially the German armed forces had a tremendous appeal.[17]

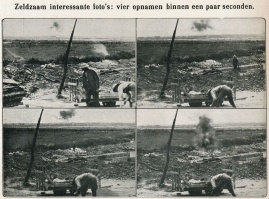

In the first few months of the war contemporaries were particularly impressed by the German artillery which was used against Belgian fortified cities such as Liège and Antwerp. Journalists reporting from Belgium desperately searched for words to transmit their experiences with the German guns. People seemed to realize that warfare had entered a new era, in which existing strongholds had become useless.[18] Generally people seemed extremely interested in the weapons that were being used in the war. Throughout the conflict the illustrated press would provide ample food for this inexhaustible curiosity with extremely detailed and vivid information about new weapons, such as the tank, the submarine, the zeppelin, and the airplane. Given the popularity of illustrated journals it seems justified to conclude that the Dutch were not just curious but outright fascinated by the actual warfare.[19]

People were also curious about the individual experiences of soldiers and other military personnel. Eyewitness accounts were very popular. As the war continued, newspapers and journals did not refrain from publishing bloodcurdling eyewitness accounts from the front. Instead, they were happy to make these type of accounts available to the public because they appreciated their authenticity. After the opening phase of the war, it was difficult for editors to meet the public’s interest for personal accounts due to many restrictions. For obtaining information about the war, media were almost entirely dependent on foreign newspapers and press agencies in the belligerent countries.[20]

This situation also explains the huge public interest in moving images from the front. Especially the British film Battle of the Somme which was screened in the autumn of 1916 attracted large crowds in Dutch cities. The over-the-top-scene, which shows soldiers climbing out of the trenches onto the battlefield, was – and to a certain extent still is – the visual climax of the film. It is striking that the documentary pays ample attention to all kinds of weaponry, especially guns. Reviews emphasized the film’s realism and authenticity, which allegedly brought the audience close to the front experience, if only in their imagination. Interestingly, in the neutral Netherlands the film was largely interpreted as propaganda for neutrality and pacifism, whereas in the United Kingdom it was considered a call for continuing support for the war.

Remembering the War↑

Neutrality also impacted how citizens commemorated and remembered the war years. The first commemoration events focused exclusively on the national experience of mobilisation. Two private associations, “Our Army” and “Our Fleet”, joined forces to erect a monument to honour and commemorate the efforts and sacrifices of the Dutch armed forces in the years 1914-1918. In 1921 the monument was unveiled in Scheveningen, on the coast near The Hague.[21] Initiated by “Our Fleet” in 1922 a monument commemorating the 58 marines who died in or as a result of the war at sea was unveiled in Den Helder in the northern part of North Holland. Den Helder is the main base of the Dutch navy.[22] Both monuments refer to the Dutch military efforts to safeguard neutrality and the Dutch victims of the war at sea. As such they appealed to a very specific segment of the population, those with an affiliation with and sympathy for the armed forces.

In 1924 an initiative was launched to commemorate mobilisation on a national scale. This seems to have engaged larger groups of the population. On 31 July 1924 church bells tolled, speeches were given, and people convened in all major cities. The next day a ceremony was held at the Scheveningen monument and a dinner was given with speeches that were broadcast on the radio.[23] This initiative was a private one in military circles with only moral support from the authorities. During the ceremonies of 31 July and 1 August, officers and ministers emphasized that the armed forces had safeguarded neutrality. They were clearly trying to convince the Dutch to continue to support the defence of neutrality. Thus, as Harmen Meek argues, the memory of the mobilisation was instrumentalised for contemporary political purposes.[24] In any case, remembrance was still oriented towards neutrality, and not towards the mass scale suffering in the belligerent countries.

This national initiative would remain a one-time event. Some mayors and others, especially students, youth leagues, and socialists, were very critical of the military character of the ceremonies. They advocated commemorations that would pay more attention to the mass suffering in belligerent societies and reject military violence. In the same period, the spiritual inspiration of humanitarian idealists and political activism of the SDAP went increasingly hand-in-hand.[25] More and more young people from different political and religious affiliations became activists against what they perceived as a war culture. They were extremely critical of any military display. Consequently, they shifted the focus of the commemoration from mobilisation to peace.[26]

The peace movement has deeply impacted public memories of the First World War as it developed since 1924. The long-term effects of the war became increasingly visible in public opinion. The primary political aim of the peace movement was disarmament. The Never-War-Again-Federation (Nooit-Meer-Oorlog-Federatie, NMOF) in particular, established in December 1924, used such a politicized memory of the war as it aimed to unite different organisations under one umbrella. Women and youth were the most active and most conspicuous groups. The NMOF emphasized the unprecedented meaninglessness and madness that in their view had characterized the war. The peace movement was very apt at using the memory of the war for the benefit of a pacifist discourse.[27] The NMOF organised an annual commemoration of the Armistice on 11 November. This alignment with commemorations in the former belligerent countries symbolizes a shift from commemoration with a focus on the mobilisation in the Netherlands to an emphasis on the war itself.[28]

During the early 1930s, the iconic image of a senseless war began to dominate public memory of the war. Foreign novels, pamphlets, and flyers fed the pacifist memory of the war and reached large audiences. After 1933 international developments made people less susceptible to the pacifist message. Although annual commemoration events continued until the late 1930s, contemporary political issues increasingly dominated the events.[29]

After 1945↑

The Second World War destroyed the “never again” ideal. This time the Netherlands would not remain neutral. After 1945 the monument in Den Helder became the venue for the commemoration of the naval victims of the Second World War. The original references to the First World War had become unreadable. The general public came to consider the monument to refer to the marine victims of the Second World War. This shows rather strikingly that after 1945 the First World War disappeared from sight as a result of the impact of the Second World War.[30] After 1989 the First World War gradually re-appeared in public discourse and in publications. In 2006 the war was included in the official canon of Dutch history, which reflects and supports the growing presence of the war in popular culture.

Today Huis Doorn, the castle where the Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941) stayed in exile until his death, is the only state-sponsored museum focusing on the First World War. For the centenary of the war, the museum created a permanent exhibition on the impact of the First World War on the Netherlands. Generally, the centenary saw a boost in public attention for the First World War.[31]

A remarkable initiative was launched regarding the Belgian Monument (Belgenmonument) near Amersfoort which was built during the war by military internees and refugees to express their gratitude to the Netherlands for the relief provided. The current refugee crisis has awakened memories of the refugees of 1914. In 2019 a Museum for Hospitality will be opened dedicated to the history of the monument and the history of refugees in the Netherlands in the 20th century.[32] However, there is no official ceremony commemorating the mobilisation or the end of the First World War. Although historians have rediscovered the First World War since 1989, as Kees Ribbens concluded in 2016, a long-term identification with the First World War seems unlikely.[33]

Conclusion↑

For the Netherlands the Great War was strictly speaking a war of others. The country did not participate militarily in the conflict and was relatively powerless. As a result, the substantial toll of a sustained general mobilisation, the actual war, and its impact on belligerent societies have largely disappeared from public memory. Today, for the majority of the Dutch the First World War is a war of others. This view does not match the experiences and views of contemporaries. The war urged not only intellectuals and public opinion leaders to reflect on the position of the Netherlands in the world. Additionally, there was a deep curiosity for information about the war, including details of actual warfare. The Dutch shared this fascination with the population of the main belligerents. However, the neutral position of the Netherlands in the conflict was decisive for the conclusions drawn. Although the First World War was a war of others for the Dutch, they were more than merely neutral bystanders.

Conny Kristel, NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies

Section Editors: Samuël Kruizinga; Wim Klinkert

Notes

- ↑ Kieft, Ewoud: Tot oorlog bekeerd. Religieuze radicalisering in West-Europa 1870-1918, PhD dissertation 2011. See also Kieft, Ewoud: Oorlogsenthousiasme. Europa 1900-1918 [Converted to War. Religious radicalisation in Western Europe 1870-1918], Amsterdam 2015.

- ↑ Brolsma, Marjet: Het humanitaire moment. Nederlandse intellectuelen, de Eerste Wereldoorlog en de crisis van de Europese beschaving (1914-1930) [The Humanitarian Movement. Dutch Intellectuals, the First World War and the Crisis of European Civilisation (1914-1939)], PhD dissertation 2015.

- ↑ Tames, Ismee: Oorlog voor onze gedachten. Oorlog, neutraliteit en identiteit in het Nederlandse publieke debat [War on our Minds. War, neutrality, and idenity in Dutch Public Debate], Hilversum 2006, pp.169-171. See also Tames, Ismee: War on our Minds. War, neutrality and identity in Dutch public debate during the First World War, in: First World War Studies 3/2 (2012): pp. 201-216.

- ↑ Blaas, P.M.B.: Geschiedenis en nostalgie. De historiografie van een kleine natie met een groot verleden. Verspreide historiografische opstellen [History and Nostalgia. The historiography of a small nation with a large past. Dispersed historiographical papers], Hilversum 2000, p. 113.

- ↑ Riemens, Michael: De passie voor vrede. De evolutie van de internationale politieke cultuur in de jaren 1880-1940 en het recipiëren door Nederland [The passion for peace. The evolution of the international political culture in the years 1880-1940 and the reception by the Netherlands], Amsterdam 2005, pp. 96-97; Moeyes, Paul: Buiten schot. Nederland tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog 1914-1918 [Out of range. The Netherlands during the First World War 1914-1918], Amsterdam 2001, p. 237.

- ↑ Riemens, De passie voor vrede [The passion for peace] 2005, p. 97; Moeyes, Buiten schot [Out of range] 2001, p. 240.

- ↑ Blom, Ron / Stelling, Theunis: Niet voor God en niet voor het Vaderland. Linkse soldaten, matrozen en hun organisaties tijdens de mobilisatie van ’14-’18 [Not for God and not for the Fatherland. Leftist soldiers, sailors and their organisations during the mobilisation of 1914-1918], Soesterberg 2004, p. 448.

- ↑ Blom / Stelling, Niet voor God en niet voor het Vaderland [Not for God and not for the fatherland] 2004, pp. 58-59, 1012.

- ↑ Tames, Oorlog voor onze gedachten [War on our minds] 2006, pp. 139-144.

- ↑ Kristel, Conny: De oorlog van anderen. Nederlanders en oorlogsgeweld, 1914-1918 [The war of others. The Dutch and the violence of war, 1914-1918], Amsterdam 2016, pp. 91-121.

- ↑ Tames, Oorlog voor onze gedachten [War on our minds] 2006, pp. 58-97.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 157-167.

- ↑ Brolsma, Marjet: Frederik van Eeden. Zelfbenoemde vredesapostel [Frederik van Eeden. Self-proclaimed apostle of peace] in: Boterman, Frits / Labrie, Arnold / Melching, Willem (eds.): Na de catastrofe. De Eerste Wereldoorlog en de zoektocht naar een nieuw Europa [After the catastrophe. The First World War and the search for a new Europe], Amsterdam 2014, pp. 213-225, esp. pp. 347-350.

- ↑ Kristel, De oorlog van anderen [The war of others] 2016, pp. 107-118.

- ↑ Klinkert, Wim: Van Waterloo tot Uruzgan. De militaire identiteit van Nederland [From Waterloo to Uruzgan. The military identity of the Netherlands], Amsterdam 2008, pp. 6, 23, 27.

- ↑ Kristel, De oorlog van anderen [The war of others] 2016, pp. 122-164.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 55-60.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 59-65.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 138-147.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 127-128.

- ↑ Schulten, Paul / Kraaijestein, Martin: Nederlandse gedenktekens van de Eerste Wereldoorlog [Dutch Memorials of the First World War], in: Binneveld, Hans et al. (eds.): Leven naast de catastrofe. Nederland tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog [Living next to the catastrophe. The Netherlands during the First World War], Hilversum 2001, pp. 163-178, esp. p. 167.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 164.

- ↑ Meek, Harmen: Mobilisatie- of Wapenstilstandsherdenking. Publieke oorlogsherinneringen in het interbellum in Nederland [Commemorating mobilisation or armistice. Public memories of war in the Netherlands during the interwar period], in: Tijdschrift voor Geschiedenis 124/1 (2011), pp. 48-63, esp. p. 52.

- ↑ Ibid., p. 53.

- ↑ Brolsma, Het humanitaire moment [The humanitarian moment] 2015, pp. 237-239.

- ↑ Meek, Mobilisatie- of Wapenstilstandsherdenking [Commemorating mobilisation or armistice] 2011, pp. 53-54.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 55-57.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 58-60.

- ↑ Ibid., pp. 60-62.

- ↑ Schulten / Kraaijestein, Nederlandse gedenktekens [Dutch memorials] 2001, pp. 166-167.

- ↑ Ribbens, Kees: Commemorating a foreign war in a neutral country. The Political Insignificance of World War I Memory in the Netherlands, in: BMGN 131/3 (2016), pp. 87-98, esp. pp. 93-96.

- ↑ Hulsman, Bernard: Een wedstrijd om de Eerste Wereldoorlog tot leven te brengen [A contest to bring the First World war to life], in: NRC Handelsblad, 28 Oktober 2016.

- ↑ Ribbens, Commemorating a foreign war 2016, p. 98.

Selected Bibliography

- Abbenhuis, Maartje: The art of staying neutral. The Netherlands in the First World War, 1914-1918, Amsterdam 2006: Amsterdam University Press.

- Blom, Ron / Stelling, Theunis: Niet voor God en niet voor het Vaderland. Linkse soldaten, matrozen en hun organisaties tijdens de mobilisatie van '14-'18 (Not for God and not for the fatherland. Leftist soldiers, sailors and their organisations during the mobilisation of ’14-’18), Soesterberg 2004: Uitgeverij Aspekt.

- Brolsma, Marjet: 'Het humanitaire moment'. Nederlandse intellectuelen, de Eerste Wereldoorlog en de crisis van de Europese beschaving (1914-1930) (thesis) (‘The humanitarian moment’. Dutch intellectuals, the First World War and the crisis of European civilisation (1914-1930)), thesis, Amsterdam 2015: Universiteit van Amsterdam.

- Brolsma, Marjet: Frederik van Eeden. Zelfbenoemde vredesapostel (Frederik van Eeden. Self-proclaimed apostle of peace), in: Boterman, Frits / Labrie, Arnold / Melching, Willem (eds.): Na de catastrofe. De Eerste Wereldoorlog en de zoektocht naar een nieuw Europa (After the catastrophe. The First World War and the search for a new Europe), Amsterdam 2014: Nieuw Amsterdam, pp. 213-225.

- Kieft, Ewoud: Tot oorlog bekeerd. Religieuze radicalisering in West-Europa 1870-1918 (Converted to war. Religious radicalisation in Western Europe 1870-1918), thesis, Utrecht 2011: Utrecht University.

- Klinkert, Wim / Kruizinga, Samuël / Moeyes, Paul (eds.): Nederland neutraal. De Eerste Wereldoorlog 1914-1918 (The neutral Netherlands. The First World War 1914-1918), Amsterdam 2014: Boom.

- Kristel, Conny: De oorlog van anderen. Nederlanders en oorlogsgeweld, 1914-1918 (The war of others. The Dutch and the violence of war, 1914-1918), Amsterdam 2016: De Bezige Bij.

- Lobbes, Tessa: Designing a peaceful world in a time of conflict. The Dutch writer Frederik van Eeden and his mission as an internationalist during World War I, in: Ayers, David / Hjartarson, Benedikt (eds.): Utopia. The avant-garde, modernism and (im)possible life, Berlin 2015: Walter de Gruyter & Co, pp. 59-71.

- Meek, Harmen: Mobilisatie- of wapenstilstandsherdenking. Publieke oorlogsherinneringen in het interbellum in Nederland (Commemorating mobilisation or armistice. Public memories of war in the Netherlands during the interwar period), in: Tijdschrift voor geschiedenis 124/1, 2011, pp. 48-63.

- Moeyes, Paul: Buiten schot. Nederland tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog, 1914-1918 (Out of range. The Netherlands during the First World War 1914-1918) (3 ed.), Utrecht 2014: De Arbeiderspers.

- Ribbens, Kees: Commemorating a ‘foreign’ war in a neutral country. The political insignificance of World War I memory in the Netherlands, in: BMGN - Low Countries Historical Review 131/3, 2016, pp. 87-98.

- Riemens, Michael: Een vergeten hoofdstuk. De Nederlandsche Anti-Oorlog Raad en het Nederlands pacifisme tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog (A forgotten chapter. The Dutch Anti-War Council and the Dutch pacifism during the First World War), Groningen 1995: Wolters-Noorhoff.

- Riemens, Michael: De passie voor vrede. De evolutie van de internationale politieke cultuur in de jaren 1880-1940 en het recipiëren door Nederland (The passion for peace. The evolution of the international political culture in the years 1880-1940 and the reception by the Netherlands), Amsterdam 2005: De Bataafsche Leeuw.

- Roodt, Evelyn de: Oorlogsgasten. Vluchtelingen en krijgsgevangenen in Nederland tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog (War guests. Refugees and prisoners of war in the Netherlands during the First World War), Zaltbommel 2000: Europese Bibliotheek.

- Schulten, Paul / Kraaijestein, Martin: Nederlandse gedenktekens van de Eerste Wereldoorlog (Dutch memorials of the First World War), in: Binneveld, Hans / Kraaijestein, Martin / Roholl, Marja (eds.): Leven naast de catastrofe. Nederland tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog (Living next to the catastrophe. The Netherlands during the First World War), Hilversum 2001: Verloren, pp. 163-178.

- Tames, Ismee: Oorlog voor onze gedachten. Oorlog, neutraliteit en identiteit in het Nederlandse publiek debat 1914-1918 (War on our minds. War, neutrality and identity in Dutch public debates 1914-1918), Hilversum 2006: Verloren.

- Tames, Ismee: 'War on our minds'. War, neutrality and identity in Dutch public debate during the First World War, in: First World War Studies 3/2, 2012, pp. 201-216.