Introduction↑

Before 1914, German towns and villages had been plastered with monuments to the dead soldiers of 19th-century conflicts. By the time war broke out, these works were deemed to be outdated or even tasteless. In an effort to improve the artistic quality of future memorial projects, central and provincial administrations set up special advice centres. At the same time, a grass-roots movement to create iron-nail "war landmarks" (Kriegswahrzeichen zum Benageln) emerged in 1915 and 1916; these were propaganda spectacles that increasingly took on a commemorative role. However, military defeat rendered these embryonic war memorials obsolete. The Ehrenmale (a term coined to distinguish them from the pre-1914 Kriegerdenkmale) which sprung up after 1918 were sombre monuments that became focal points of both personal mourning and political mobilisation. However, the contrast between the personal and the political should not be exaggerated: a large grey area divided the two, and it was precisely this grey space into which the memorial makers were venturing. Displays of revanchism were not as prevalent as some scholars have suggested even though they created a great deal of noise, notably at the Tannenberg memorial in East Prussia.

Agents of Remembrance↑

Commemorative networks linked five main players: memorial committees, veterans, families, artists, and the state. In collaboration with artists, second- and third-order elites within civil society played the most active and creative part. The general public, notably the bereaved families, had a say too, but in some cases consultation was a mere formality. The organising committees were normally the driving force behind the memorialisation of the war. Their composition was intended to make them representative of the local community as a whole, although local worthies and public-spirited individuals who were seen (or saw themselves) as representing communal interests were often taken to be representative. In any case, the committees remained answerable to the public whose support (financial and moral) was vital to sustain the virtual consensus of need.

The input of veterans was critical in communal commemorations, for they regularly sat on memorial committees. They were equally prepared to seize the initiative in building local war monuments. Despite this, the veterans rarely spoke with one voice. A dividing line ran between the traditional Kriegervereine (and their umbrella organisation, the Kyffhäuserbund) on the one hand, and the Kampfbünde or Wehrverbände, newly founded paramilitary associations which were themselves split along the borders of different socio-political milieux, on the other. The aspect of war commemoration was built into the associational life of war veterans. Certainly, the majority of those who came home from war remained aloof from the veterans’ movement. Nevertheless, the membership figures of the German associations are impressive, particularly when compared to British associations.

Memorial committees entrusted the actual memorial design to architects or sculptors who had won public competitions or been directly invited to create First World War memorials. Most designers were prepared to conform to the expectations of their clients, but managed to retain their artistic independence within the limits set by the popular taste. However, the issue of good taste brought further agents into the commemorative arena. Artistic institutions issued advisory circulars urging local committees to consult a competent artist instead of a monumental mason or a landscape gardener. The state, too, saw the need to ensure that commemorative monuments met basic aesthetic standards. The Reichskunstwart (Reich Art Custodian), a senior civil servant attached to the ministry of the interior, made generic recommendations, as did the advice centres set up by state and provincial governments during the war. In Prussia, for instance, consultation was, in theory, mandatory – refractory communities faced stiff fines – but was, in reality, rarely enforced. The advice centres, composed largely of civil servants, church officials, art historians, and artists, preferred cooperation over confrontation in order to maintain the consensus built up around a memorial scheme. Strong voluntary initiative and a reluctant state were thus the basic ingredients of war remembrance at the local level.

Weimar’s politicians did not try to impose a national monument from the top. In 1924, Reich President Friedrich Ebert (1871-1925) announced the state’s wish to realise a Reichsehrenmal. This unleashed a prolonged, highly localised debate about the form and location of the national memorial. Ebert’s vision did not materialise during the Weimar years. However, the public discussion shows that the social organisation of war remembrance was decentralised. Even though the Reich Art Custodian acted as the governmental coordinator and spokesperson, the vast majority of the roughly three hundred proposals that reached him originated from civil society, its local communities and voluntary associations. However, the nationwide discussion, recorded and reported by the Reich Art Custodian, influenced local discourses of commemoration in its turn. Hence, collective memories arose out of a dialogue between high politics and vernacular culture; from a dialogue between agents working within state institutions and civil society.

Unknown Soldiers↑

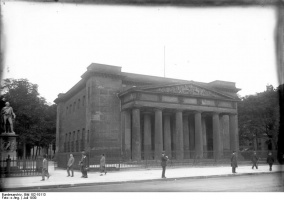

The burial of the Unknown Soldier in Paris and the Unknown Warrior in London on 11 November 1920 set a precedent for a new type of national war memorial throughout Europe in the inter-war period. Germans, too, felt the need to bring their dead home and put them to rest, at least symbolically. The Reich Art Custodian stimulated discussion about a German Unknown Soldier. In an article published in the left-liberal Berliner Tageblatt in summer 1925, he suggested interring an "Unknown Dead Man" in the River Rhine as a memorial to all of Germany’s fallen. The location had symbolic significance: it was supposed to connect the war dead to the golden treasure of the Nibelungen. Both the proposed site and the idea itself proved controversial, and alternative proposals for Reich memorials at Bad Berka or in the capital, Berlin, did not include the symbol of the Unknown Solider.

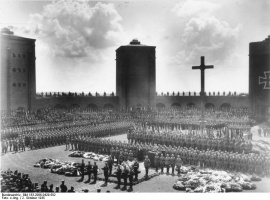

Due to regional rivalries and political factionalism, the entire project of a German national or Reich memorial did not get off the ground until after the Nazis had come to power. In October 1935, Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) personally declared the Tannenberg memorial a Reich memorial. Ultra-conservative groups, however, had laid the foundation stone as early as 1924. Built in a style reminiscent of the castles of the Teutonic Knights, the memorial’s architecture appeared to protect the grave erected at its centre. The bodies of twenty unidentified German soldiers from the Eastern Front were entombed underneath a huge metal cross. Tannenberg constitutes a German transformation of the Anglo-French tradition. The Unknown Soldier – who originally represented the recovery and restoration of the individual – had been turned into a symbol of the völkisch community.

The inventors of the mass grave at Tannenberg imagined therein a new community of the dead. However, the twenty unknown German soldiers did not rest in peace. Under the regime of Adolf Hitler, who fancied himself the incarnation of the Unknown Soldier, all twenty were reburied as part of a scheme to redesign the memorial. In 1935, Tannenberg was re-launched as the mausoleum of the recently deceased hero of the battle of 1914, Paul von Hindenburg (1847-1934). The dead were thus subsumed into the cult of military leadership. Already deprived of their individuality, they were now subjected to the oligarchy of commemoration. At Tannenberg, the notion of elite heroism superseded the idea of equality of sacrifice which had been intrinsic to the genuine Unknown Soldiers in Paris and London.

Stefan Goebel, University of Kent at Canterbury

Section Editor: Christoph Nübel

Selected Bibliography

- Goebel, Stefan: The Great War and medieval memory. War, remembrance and medievalism in Britain and Germany, 1914-1940, Cambridge; New York 2007: Cambridge University Press.

- Hettling, Manfred / Echternkamp, Jörg: Deutschland. Heroisierung und Opferstilisierung. Grundelemente des Gefallenengedenkens von 1813 bis heute, in: Hettling, Manred / Echternkamp, Jörg (eds.): Gefallenengedenken im globalen Vergleich. Nationale Tradition, politische Legitimation und Individualisierung der Erinnerung, Munich 2012: Oldenbourg.

- Mosse, George L.: Fallen soldiers. Reshaping the memory of the world wars, New York 1990: Oxford University Press.

- Schneider, Gerhard: In eiserner Zeit. Kriegswahrzeichen im Ersten Weltkrieg. Ein Katalog (1 ed.), Schwalbach 2013: bd-edition.

- Winter, Jay: Commemorating war, 1914-1945, in: Chickering, Roger / Showalter, Dennis / Van de Ven, Hans (eds.): The Cambridge history of war. War and the modern world, volume 4, Cambridge 2012: Cambridge University Press, pp. 310-326.

- Ziemann, Benjamin: Contested commemorations. Republican war veterans and Weimar political culture, Cambridge; New York 2013: Cambridge University Press.