Introduction↑

The fighting forces of all nations suffered terrible losses during the Great War. Some nine million soldiers were killed on the battlefields, while millions of civilians died through direct attack, disease brought on by malnutrition, and even genocide.[1] For Canada, a country of not yet eight million, the Canadian Expeditionary Force’s (CEF) 61,122 wartime dead was a tremendous shock. Several thousand more Canadians died in the war’s aftermath, and Newfoundland’s deaths (not a part of Canada during the war but now included in the country’s wartime dead since it joined the Confederation in 1949) add to the ghastly toll. These fatalities were especially devastating since Canada’s previous war, the South African War of 1899-1902, saw 7,368 Canadians serve with 270 dying in the conflict.[2] This article will explore the Canadian wartime and postwar deaths, and provide some analysis of the available sources and statistics.

Background↑

Canadian casualty figures are difficult to determine in part because of incomplete sources and the normal vagaries of record-keeping in times of war. It is generally said that 66,000 Canadians were killed in total, and this is the figure most frequently used by the Canadian government in official documentation. This article seeks to be more accurate and it will try to provide a source for each figure. Other scholars may further refine the figures, but at least there will be a roadmap of sources.

Most of the accepted Canadian statistics from the First World War come from G.W.L. Nicholson’s (1902-1980) 1962 official history, The Canadian Expeditionary Force.[3] This late date for an official history was the result of an earlier project, headed by Colonel A.F. Duguid (1887-1976), which produced only a single volume from a planned eight-volume series, and that only in 1938.[4] Duguid’s failed history stifled the writing of the Great War in Canada for many decades. A rapidly-produced official medical history published in 1925 by Sir Andrew Macphail (1864-1938), a wartime doctor and a respected man of letters, was flawed and poorly reviewed.[5] It was polemical, rushed, and based on a small sampling of official records. Its statistics were soon proven to be uneven and they are little used today. However, Nicholson’s First World War book has stood for more than fifty years and it is the foundational text for all subsequent histories, even if historians have modified, edited, and rewritten large parts of it. Nicholson’s maps and statistics have had the most enduring value.

Canada’s Wartime Military Fatalities↑

Canada’s wartime military fatal losses are as follows, with more contextualizing information provided below. The statistics presented are for those who served and perished in the Canadian Expeditionary Force, Royal Canadian Navy, and Canadians who died in the British flying services.

| Service | Deaths |

| Canadians serving in the Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1914-1920 | 59,544[6] |

| Canadians serving in the Royal Canadian Navy | 190[7] |

| Canadians serving in the British flying services | 1,388[8] |

| Total war deaths for Canadians in uniform | 61,122 |

Table 1: Canada's Wartime Military Fatalities.

While Newfoundland was not part of Canada during the First World War, 1,305 Newfoundlanders were killed during the war.[9] Most Newfoundlanders served in the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, but also in the Royal Navy and in forestry units. Several thousand also enlisted in Canadian units and some like Private Tommy Ricketts (1901-1967) were awarded the Victoria Cross for uncommon valour on the battlefield. Since Newfoundland joined Confederation, the Newfoundland war effort has become incorporated into that of Canada, and Newfoundland’s wartime deaths are usually added to Canada’s, albeit with the above caveat. If the Newfoundland figures are added to Canadian deaths (61,122), then the total is 62,427. But there are additional deaths that are included in the total losses, with deaths extending to 1921 or 1922 depending on the source. The 61,122 figure of Canadian deaths does not include the tens of thousands of Canadians who joined the British army and navy, as well as other nations’ forces of whom an unknown number perished. There is no complete record of these Canadians, but it is thought that as many as 40,000 served and several thousand were likely killed.[10]

Number Who Served↑

In Canada, 619,636 men and women were attested during the war and officially served in the Canadian Expeditionary Force. The women were all nurses; 3,141 enlisted and 2,504 served overseas. Statistics of death vary, but at least 46 died, including twenty-one killed as a result of direct enemy action.[11] The 619,636 figure does not include those who enlisted in the Royal Navy, directly into the Royal Flying Corps, or other Imperial services.[12] Of those who enlisted, 424,589 served overseas as part of the CEF.

Another 8,826 Canadians sailed with the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) during the war, along with 673 Royal Navy and Royal Navy Reserve officers for a total of 9,499 sailors. The RCN expanded rapidly during the war to meet the crisis at sea, especially on the east coast, and it grew from a handful of aged warships to 134 commissioned vessels by war's end. The newest naval official history, The Seabound Coast, notes 190 men in RCN service were killed in action or accidents. The figure included those killed in uniform in the devastating Halifax Explosion of December 1917 that destroyed much of the crucial naval city, a blast that killed more than 1,600 civilians.[13] While millions of Canadians worked in support of the war, in factories, businesses, and on farms, there are no statistics related to civilian wartime-related deaths. Nor is there a casualty figure for those 3,000 or so Canadians in service with the Royal Navy, but some did not live to see the end of the war. In fact, the first Canadians to die on active service were four Canadian sailors aboard HMS Good Hope, a British armoured cruiser sunk on 1 November 1914 at the Battle of Coronel.[14]

While Canada had no independent Canadian flying service until the last months of the war, 13,160 Canadians served as aircrew in the flying services, plus 9,652 as ground crew. Many of these men had initially enlisted with the CEF, later transferring into the flying services, and so most were counted in the 619,636 figure. In 1980, the Canadian First World War air force official history, S.F. Wise’s (1924-2007) Canada’s Airmen, revealed after exhaustive research that 1,388 Canadians were killed. Almost a third, 32.9 percent, died in accidents, reflecting the hazards of flying and training.[15] Another 1,130 were injured or wounded, with 377 becoming prisoners of war.

Cause of Fatalities↑

Most soldiers died in battle. Of the 425,000 Canadians who served overseas, 51,748 soldiers and nursing sisters were killed in action or died of their wounds. Their lives ended in all manner of grisly ways, although artillery was the great killer of the war, with 58 percent of casualties from all causes.[16] However, losses to small arms fire, primarily it is thought from machine gun bullets, rose in 1918, as German artillery was overpowered in sophisticated counterbattery fire and defenders relied on machine guns. Poison gas also led to more casualties from mid-1917, with its heavier and frequent use, especially mustard gas. There is no accepted figure for the number of Canadians killed by gas.

While all deaths were tragic, it was revealed publicly towards the end of the 20th century that twenty-five Canadians were executed by firing squad, most of them for running away from the front and being Absent Without Leave.[17] These deaths were seen as particularly awful by later Canadians who grew up being taught about the futility of the war.

All but forgotten by Canadians were the thousands of deaths from disease. Unlike the South African War, where more Canadian soldiers died from disease than bullets, the opposite marked the First World War. Advances in preventative medicine and surgery, along with fastidious attention to preventative measures related to human waste and sanitation, kept the losses manageable.[18] “The great, outstanding feature of the War,” wrote McGill University’s Dr. George Adami (1862-1926), who served overseas, “has been the triumph of preventative medicine.”[19] While trench fevers transmitted by lice and other ailments plagued the soldiers, most did not succumb in any sort of widespread death, save for the Spanish flu in 1919 (which will be discussed below). Nonetheless, 7,796 Canadians died of disease or were killed in accidents, the latter including everything from being kicked by horses, to falling down stairs, to being run over by vehicles.[20]

In all, some 50,000 Canadians were killed by the Spanish Influenza in 1918 and 1919, almost reaching the ghastly figure of wartime dead over four years.[21] Inaccurate record keeping in this time of tremendous crisis has not allowed historians to pinpoint the exact number of deaths. Macphail reported 776 deaths to service personnel from the flu, but this is likely an underestimation.[22]

Distribution of Fatalities↑

The losses at the front were not distributed evenly, with the front-line infantry and machine-gunners in the greatest danger. They suffered the vast majority of casualties, just as they formed the largest part of the Canadian infantry divisions. Of the roughly 345,000 Canadians that went to France, 236,618 rank and file passed through the 50 Canadian infantry battalions (two were broken up) that served in France and Belgium.[23]

The four Canadian divisions, with a full strength of around 18,300 to 21,000 depending on the point in the war, had tens of thousands of additional soldiers pass through them in the course of the war due to constant casualties. The 4th Division had 50,306 rank and file attached to it; the 3rd Division, 55,634; the 2nd Division had 59,186; and the 1st Division, in theatre the longest since February 1915, had 71,492 rank and file serve in the Old Red Patch. These figures do not include officers.[24] On the Somme, the infantry arm accounted for 93 percent of the deaths in action.[25] From August 1916, when the Canadian Corps reached its maximum strength of four divisions, to November 1918, the corps lost on average 6,041 men killed, evacuated for wounded, injury, or illness, or transferred per month.[26]

While there was a constant wastage in the trenches to shell, snipers and disease, the set-piece battles resulted in the greatest slaughter of soldiers. The first day of the Battle of the Vimy Ridge, 9 April 1917, was the single bloodiest day of the war, with over 2,500 dead, and in all of Canadian military history.[27] The Hundred Days campaign, a series of battles from Amiens on 8 August 1918 to the liberation of Mons on 11 November, cost a staggering 45,835 casualties, about 18 percent of the total battle casualties.[28] Even successful battles or campaigns resulted in crippling losses. At Vimy in April 1917, the casualty rate for Canadian forces committed was 16 percent and 13 percent at Amiens in August 1918.[29]

The numbers of casualties listed below come from Nicholson’s official history. Historians have generally accepted them, although there have been some re-evaluations. The casualty figure includes wounded and dead and the ratio was usually 3 to 1, although it could go as low as 2 to 1 as on the Somme. The Second Battle of Ypres casualties of 6,714 would equate to about 2,200 fatalities.

| Battle or Campaign | Dates | Casualties

|

| Second Battle of Ypres† | 15 April – 3 May 1915 | 6,714 |

| Festubert | 15 - 25 May 1915 | 2,468 |

| St Eloi Craters | 4 -16 April 1916 | 1,373 |

| Mount Sorrel | 2 - 13 June 1916 | 8,000 |

| Somme | 31 August - 18 November 1916 | 24,029 |

| Vimy Ridge | 9 - 14 April 1917 | 10,602 |

| Hill 70 | 15 - 25 August 1917 | 9,198 |

| Passchendaele | 26 October - 10 November 1917 | 15,654 |

| Hundred Days | 8 August – 11 November 1918 | 45,835 |

† includes the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry serving with the British Army

Table 2: List of Casualities as recorded in 1920.[30]

Losses for the battles listed above were tabulated in the 1920s by the Department of National Defences’ Historical Section for the battles’ delineated time period. For example, the Battle of Vimy Ridge is considered to have been fought from 9 to 14 April, but several thousand Canadians were killed or wounded in the four months preceding it, which was filled with heavy raiding on the enemy lines, dangerous training, and the usual wastage in holding the trenches.

Died of Wounds↑

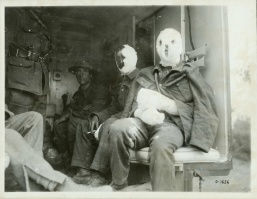

If soldiers died in the planning and preparation for the official battles, there were also soldiers who were wounded in battle and who later died of wounds. 172,950 members of the Canadian Expeditionary Force were wounded (plus another 1,130 airmen). Of this CEF total, 138,166 suffered non-fatal battle casualties, with the rest being accidents and injuries not associated with combat.[31] Some of the wounds were light in nature, ranging from broken bones to bullets passing through flesh or a scalp wound. Other wounds were horrifying in their severity, forever maiming and crippling. Statistics showed that 93 percent of those who reached medical treatment survived their injuries, but many wounded were lost or unreachable and never passed through the medical system, thereby indicating a much lower survival rate.[32] This was especially true when terrain was muddy and cratered, such as the Somme and Passchendaele battlefields, or during fighting retreats like Second Ypres, St. Eloi, and Mount Sorrel and other failed attacks, where the wounded were left unattended in No Man’s Land.

The wounded who received medical care generally survived, but many had their lives cut short or significantly diminished. There were some 11,536 recorded cases of gas poisoning, although many more men suffered from unrecorded gas attacks, especially during 1918 when it polluted the battlefield.[33] Many of these soldiers died of their wounds long after the Armistice of 11 November 1918. Their deaths were surely a result of the war.

Grief, Missing, and Loss↑

Grief from deaths overseas pervaded Canada – there were few families that did not experience loss directly or indirectly. Telegrams and letters starkly informed next of kin of a loved one killed. Official documentation confirmed a soldier, sailor, nurse, or aviator’s fate, but families often held out that these were wrong, or a case of confused identification. Rarely a reprieve came in the form of a letter from a loved one still alive; most often, the soldiers were indeed killed, although some family members maintained hope for years. The deceased soldier’s possessions were sent home and families treasured letters, a few photographs, and their memories. Fellow soldiers and superiors might write the next of kin about their loved ones and the manner of their deaths.

Some soldiers’ deaths could not be confirmed. Nicholson provides a final total of 4,434 missing for all ranks.[34] This was a tally made well after the war, as the number reported missing were far higher in the immediate aftermath of battle. For instance, following the Battle of Ancre Heights on 1 October 1916, where the Canadians attacked and were driven back from Regina Trench, the Canadian Corps reported that 21 percent of its casualties were men missing.[35] After a battle or raid, soldiers did not return to their units, and it was presumed they were killed or taken prisoner. Some 3,847 Canadians became guests of the Kaiser.[36]

The missing remained in a purgatory: neither officially dead nor living – simply disappeared. Families hoped for news. It rarely came. Occasionally, a man might turn up in a German prisoner of war camp or their body found and identified. More often, after many months or years, a missing man was declared killed. There were no bodies and therefore no graves. In other cases, bodies were recovered during battlefield clearances but with no identification, hence the numerous graves with only “A Solider Known unto God.” On the Somme in 1916, 55 percent of all the Canadian fatalities have no known graves.[37] After the war, their names were captured on monuments. The Menin Gate monument, erected in Ypres, contains 6,940 Canadian missing soldiers, those who died on Belgian soil and have no known graves.[38] The Vimy Monument contains the names of 11,285 missing who died in France with no known graves. 1,011 Canadians are buried at Tyne Cot on the Passchendaele battlefield, some with or without graves and names. Other airmen are listed on the Arras Flying Services memorial.

Total Fatalities↑

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission, which was charged with caring for the Commonwealth’s war dead, used 31 August 1921 as the official end of the war to calculate the war’s dead. From 4 August 1914 to 31 August 1921, it lists 64,962 Canadian and Newfoundlander fallen in its care. Tim Cook's research in Shock Troops revealed that, of these, 3,792 of the dead passed away from 1919 to 1921.[39] These were men who died from injuries, illness, flu, and misfortune in waiting to return to Canada, or before being demobilized. It also includes those whose wounds during the war meant they were still under medical treatment and passed away.

Canada’s ornate Books of Remembrance are held in the Peace Tower at the House of Commons in Ottawa. The memorial books were started in the early 1930s and contain the names of Canada’s killed wartime personnel. The books contain the names of 66,755 Canadians and Newfoundlanders who were killed during the Great War. The number continues to grow as the Department of Veterans Affairs discovers new veterans who died of their war wounds before the cut-off date of 30 April 1922. While it is not clear from the records why Canada’s cut-off date for the war’s dead differed from the CWGC, the two sets of figures are different. Any Canadian or Newfoundlander who served overseas, and who died up to 30 April 1922, were included in the books, even though some of these veterans died with no identifiable wartime injury. Newfoundland’s wartime dead is usually cited as 1,305, but there are 1,656 dead listed in the Newfoundland Book of Remembrance.

The total number of CEF enlistments amounted to 32.2 percent of the military-age men in Canada and the total Canadian deaths excluding Newfoundland recorded up to 1922 were 3.38 percent of the military-age cohort.[40] Of those that served in the CEF, 10.5 percent died in the war, while the corresponding percentage for those who reached overseas was 15.1 percent.

Conclusion↑

Canada’s total wartime military dead for those who served in a Canadian uniform range from 61,122 (and 62,427 if Newfoundland is included) to 66,755 Canadians and Newfoundlanders listed in the Books of Remembrance. These figures do not include those who served in the other armed forces or those who died of their wartime wounds after 30 April 1922.

Tim Cook, Canadian War Museum

William Stewart, Independent Scholar

Reviewed by external referees on behalf of the General Editors

Notes

- ↑ Ferguson, Niall: The Pity of War, New York 1999, p. 295; Eksteins, Modris: Memory and the Great War, in: Strachan, Hew (ed.): The Oxford Illustrated History of the First World War, Oxford 1998, p. 307.

- ↑ Miller, Carman: Painting the Map Red. Canada and the South African War, 1899-1902, Montreal 1993, p. 429.

- ↑ Nicholson, G.W.L.: Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1914-1919, Montreal 2015 (1962).

- ↑ Duguid was overwhelmed by the task and a host of other issues that fell to his small historical section, and while his researchers arranged the millions of pages of documentation and tried to make sense of the mass of information, he made little headway into the writing. See Cook, Tim: Clio's Warriors. Canadian Historians and the Writing of the World Wars, Vancouver 2006.

- ↑ Macphail, Andrew and Canada. Dept. of National Defence. Historical Section: Official History of the Canadian Forces in the Great War, 1914-19. The Medical Services, Ottawa 1925.

- ↑ Nicholson, Canadian Expeditionary Force 2015, p. 548. This figure includes Canadians killed in France and Belgium, as prisoners of war, in Britain and Canada, and in other theatres of war such as Siberia, North Russia, Palestine, Bermuda, St. Lucia, and while travelling at sea.

- ↑ Johnston, William et. al.: The Seabound Coast. The Official History of the Royal Canadian Navy, 18967-1939, volume I, Toronto 2010, pp. 723-24.

- ↑ See Wise, S. F.: Canadian Airmen and the First World War, vol. 1, Toronto 1980, p. 645.

- ↑ For the Newfoundlanders, see Nicholson, Gerald W. L.: The Fighting Newfoundlander. A History of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, Carleton Library Series, Montreal 2006, pp. 508-9 and Steele, Owen William and Facey-Crowther, David R.: Lieutenant Owen William Steele of the Newfoundland Regiment. Diary and Letters, Montreal et al. 2002, p. 13.

- ↑ Love, David W.: A Nation in the Making. The Organization and Administration of Canada’s Military in World War One, Ottawa 2011, p. xv.

- ↑ Toman, Cynthia: Sister Soldiers of the Great War. The Nurses of the Canadian Army Medical Corps, Vancouver 2016, p. 110.

- ↑ LAC, Records of the Department of National Defence (RG 24), 10-47E, v. 1843, Scott to Secretary, Office of the High Commissioner, 3 September 1930; Sharpe, C.A. : Enlistment in the Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914-1918. A Regional Analysis, in: Journal of Canadian Studies 18/4 (1983-84), pp. 17-19.

- ↑ Johnston, The Seabound Coast 2010, pp. 723-4.

- ↑ Elson, Bryan: First to Die. The First Canadian Navy Casualties in the First World War, Halifax 2010.

- ↑ See Wise, Canadian Airmen 1980, p. 645.

- ↑ Strong, Paul / Marble, Sanders: Artillery in the Great War. Barnsley 2011, e-book, loc 55.

- ↑ Morton, Desmond: When Your Number's Up. The Canadian Soldier in the First World War, Toronto 1993, p. 250; Iacobelli, Teresa: Death or Deliverance. Canadian Courts Martial in the Great War, Studies in Canadian Military History, Vancouver 2013.

- ↑ See Cook, Tim: Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Canadian Medical Officers in the Great War, in: Craig, Stephen / Smith, Dale C. (eds.): Glimpsing Modernity. Military Medicine in World War I, Newcastle upon Tyne 2015, pp. 34-59.

- ↑ Morton, When Your Number's Up 1993, p. 204.

- ↑ Nicholson, Canadian Expeditionary Force 2015, p. 548.

- ↑ Humphries, Mark Osborne: The Last Plague. Spanish Influenza and the Politics of Public Health in Canada, Toronto 2013, p. 128.

- ↑ Macphail and Canada. Dept. of National Defence. Historical Section, Official History 1925, p. 266.

- ↑ Figures from LAC, RG 24, v. 1820, file GAQ 5-14, The Canadians in the Great War.

- ↑ LAC, RG 24, v. 1821, file GAQ 5-16, Total and average number of other ranks who passed through the four divisions infantry battalions.

- ↑ Stewart, William F.: The Canadians on the Somme, 1916. Canada's Neglected Campaign, Wolverhampton Military Studies, Solihull (forthcoming 2017), Table C.7 Death by Arm/Branch.

- ↑ Holt, Richard Gottfrid Larsson: Filling the Ranks. Recruiting, Training and Reinforcements in the Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914-1918, PhD dissertation, University of Western Ontario 2011, p. 451.

- ↑ See Cook, Tim: Vimy. Battle and Legend, Toronto 2017.

- ↑ Schreiber, Shane B.: Shock Army of the British Empire. The Canadian Corps in the Last 100 Days of the Great War, Westport 1997.

- ↑ Stewart, William F.: The Embattled General. Sir Richard Turner and the First World War, Montreal et al. 2015, p. 96.

- ↑ Nicholson, Canadian Expeditionary Force 2015.

- ↑ Nicholson: 548; Nicholson, Canadian Expeditionary Force 2015, p. 548.

- ↑ Morton, When Your Number’s Up 1993, p. 181.

- ↑ On Canadian gas casualties, see Cook, Tim: No Place to Run. The Canadian Corps and Gas Warfare in the First World War, Vancouver 1999.

- ↑ Nicholson, Canadian Expeditionary Force 2015, p. 548.

- ↑ LAC, RG 9, v 4813 Canadian Corps GS War Diary, Summary of Operations, 7 October 1916, RG9 III-D-3 v4813, LAC.

- ↑ Vance, Jonathan: Objects of Concern. Canadian Prisoners of War through the Twentieth Century, Vancouver 1994, p. 254.

- ↑ Stewart, The Canadians on the Somme (forthcoming 2017), Table C.6 Identified Graves and Missing.

- ↑ This number is different in many sources, but this figure comes from the Department of Veterans Affairs website. Online: http://www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/remembrance/memorials/overseas/first-world-war/belgium/Menin.

- ↑ Figures compiled from the CWGC database. See Cook, Shock Troops 2008, p. 618.

- ↑ Note these figures are the upper bounds as substantial numbers of those who served in the CEF came from the United States and other countries, while the population numbers refer only to those residing in Canada. Ongoing research suggests the figure of Americans who enlisted in the CEF amounted to 60 to 90,000 men. Sharpe, Chris: Enlistment in the Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914-1918, in: Canadian Military History 24/1 (2015).

Selected Bibliography

- Cadigan, Sean T.: Death on two fronts. National tragedies and the fate of democracy in Newfoundland, 1914-34, Toronto 2013: Allen Lane.

- Cook, Tim: No place to run. The Canadian Corps and gas warfare in the First World War, Vancouver 1999: University of British Columbia Press.

- Cook, Tim: Vimy. The battle and the legend, Toronto 2017: Allen Lane Canada.

- Cook, Tim: Shock troops. Canadians fighting the Great War, 1917-1918, volume 2, Toronto 2008: Viking Canada.

- Cook, Tim: At the sharp end. Canadians fighting the Great War, 1914-1916, volume 1, Toronto 2007: Viking Canada.

- Godefroy, Andrew B.: For freedom and honour? The story of the 25 Canadian volunteers executed in the First World War, Nepean 1998: CEF Books.

- Humphries, Mark Osborne: The last plague. Spanish influenza and the politics of public health in Canada, Toronto; Buffalo 2013: University of Toronto Press.

- Iacobelli, Teresa: Death or deliverance. Canadian courts martial in the Great War, Vancouver 2013: University of British Columbia Press.

- Johnston, William Cameron: The seabound coast, Toronto 2010: Dundurn Press.

- Macphail, Andrew: Official history of the Canadian forces in the Great War 1914-19. The medical services, Ottawa 1925: Acland.

- Morton, Desmond: When your number's up. The Canadian soldier in the First World War, Toronto 1993: Random House of Canada.

- Nicholson, Gerald W. L.: Canadian Expeditionary Force, 1914-1919. Official history of the Canadian army in the First World War, Ottawa 1962: R. Duhamel.

- Toman, Cynthia: Sister soldiers of the Great War. The nurses of the Canadian Army Medical Corps, Vancouver 2016: University of British Columbia Press.

- Vance, Jonathan F.: Death so noble. Memory, meaning, and the First World War, Vancouver 1997: University of British Columbia Press.

- Vance, Jonathan Franklin William: Objects of concern. Canadian prisoners of war through the twentieth century, Vancouver 1994: University of British Columbia Press.

- Wise, S. F.: Canadian airmen and the First World War, Toronto 1980: University of Toronto Press.