Introduction – Finance and War, the French case↑

Finance and war issues have long been mutually coextensive: states needed finance mostly to fund war, while one of war’s main aims was access to tributes, taxes or plunder. The effect of military spending upon the state’s size was limited during the 19th century in Western Europe, and opened the opportunity to non-military public expenses growth, thanks to a long period of relative peace.[1] Nevertheless, this relative decline in military spending was not as pronounced and as beneficial to state finance in France as in most neighbouring countries, for two main reasons: slow demographic growth and lost wars. Indeed, from 1813 on, France was defeated in many conflicts – 1813-1814, 1815, 1870-1871 – and ended up burdened by huge payments to its opponents, to which new military expenses added, particularly in the decades following its 1871 defeat (Table 1).[2]

| |

|

|

||||

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| France | |

|

|

|

|

|

| Italy | |

|

|

|

|

|

| Russia | |

|

|

|

|

|

| United Kingdom | |

|

|

|

|

|

| Austria-Hungary | |

|

|

|

|

|

| Germany | |

|

|

|

|

|

| Total | |

|

|

|||

Table 1: The costs of the “armed peace” to the larger European nations, 1873-1913, in million dollars[3]

Thus, when France faced the possibility of a European war in the early 1910s, it bore the largest public debt in the world, but also a strong experience regarding war finance. Moreover, many measures had already been planned or even implemented in order to fund the war, preserve the French payment system and avoid a dire financial crisis in case of a general conflict. From this perspective, World War I (WW1) finance in France started years ahead of August 1914 through provisions and planning. Nevertheless, all plans were overwhelmed by the unexpected costs and length of the conflict. At the end of the war France implemented a disastrously inefficient financial policy, wasting many of the benefits of a costly victory. These issues were heavily documented during the interwar period thanks to political skirmishes, parliamentary debates, American foundations and persistent financial conflicts between foes but also between former allies.

War finance on the eve of WW1↑

In 1913, the French state was heavily indebted, over 33 billion French francs (FF),[4] a debt accumulated for a great part to prepare for colonial and continental war or to pay for defeat. To be sure, the cost of this debt was limited due to the huge amount of French savings and the general trust towards French public finance, mirrored in the low interest rates paid by the state on its debt. Moreover, as the second (next to London) financial market in the world, and the first for public securities, Paris offered the best possible financial conditions to the French state. Nevertheless, the amount of fiscal resources devoted to debt interest payments stood at 34 percent in 1913. Worse though, the increase in military expenses following the first Moroccan crisis, in 1905, had led to temporary measures and special Treasury accounts that dissimulated the real budgetary conditions. The rising international tensions after 1911 further increased military expenses, while Parliament proved incapable of voting a budget on schedule. The state functioned mainly upon “provisional twelfth”, i.e. monthly sums calculated from the previous year’s budget before the current year’s budget was voted. The situation got worse in 1913, with the “three years” law extending compulsory military service. All this led to the accumulation of over 1.2 billion French francs in floating debt to be consolidated. This process was hampered by political strife over tax issues, crucially the tax on rentes – the French state perpetually consolidated loans that had been tax-free since 1797. Finally, a consolidation loan was offered to the public in July 1914 (Table 4). It was too late to tidy up public finance, but left the syndicated banks burdened with unsold rentes when the crisis broke out. Besides, this explains why from 1911 on budget figures are both contradictory and unreliable, a situation that further deteriorated during the war, until 1926/1928 (Table 2).

But this liability side was somehow balanced by a favourable asset side, partly the result of the slow French demographic movement and partly the result of a voluntary policy. Thanks to the fertility decline and a thrifty mentality, which led to a long-term balance of payment surplus, France was the second creditor nation with over 45 billion francs in foreign assets in 1914.[5] This position had already been used to settle foreign transactions in 1870 and fund the 1871 Emprunt de libération nationale, and in 1914 the foreign securities portfolio was seen as a major asset to collateralize or finance foreign loans.[6]

| |

|

|

||||||||||

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1911

|

4.7

|

|

|

|

|

4.7

|

4.5

|

|

|

|

4.5

|

0.2

|

| 1912

|

4.9

|

|

|

|

|

4.9

|

4.7

|

|

|

|

4.7

|

0.2

|

| 1913

|

5.1

|

5.1

|

5

|

|

|

|

5

|

0.1

|

||||

| 1914

|

4.2

|

3.9

|

1.9

|

0.5

|

0.05

|

10.55

|

2

|

6.5

|

0.5

|

1.4

|

10.4

|

0.15

|

| 1915

|

4.1

|

1.2

|

8

|

6.7

|

2.8

|

22.8

|

2.5

|

14.7

|

3.1

|

1.8

|

22.1

|

0.7

|

| 1916

|

4.9

|

2.4

|

12.4

|

5.8

|

8.8

|

34.3

|

2.8

|

23.9

|

6.8

|

3.3

|

36.8

|

-2.5

|

| 1917

|

6.6

|

5

|

12.6

|

5.7

|

11.9

|

41.8

|

4.1

|

28.7

|

7

|

4.8

|

44.6

|

-2.8

|

| 1918

|

7.2

|

4.8

|

3.7

|

22.5

|

8.7

|

46.9

|

5.4

|

36.1

|

8.1

|

7

|

56.6

|

-9.7

|

| 1919

|

11.6

|

8.4

|

26.2

|

7.3

|

11.3

|

64.8

|

9.2

|

18.2

|

18.9

|

7.9

|

54.2

|

10.6

|

| 1920

|

20.1

|

0.8

|

3.5

|

35.5

|

-0.5

|

59.4

|

11.4

|

7.6

|

27.4

|

11.7

|

58.1

|

1.3

|

| 1921

|

23.1

|

-2

|

10.3

|

9.1

|

2.7

|

43.2

|

9.9

|

6

|

24.1

|

11.1

|

51.1

|

-7.9

|

| 1922

|

24.2

|

24.2

|

7.7

|

5

|

22.6

|

13.6

|

48.9

|

-24.7

|

||||

| 1923

|

27.7

|

27.7

|

6.5

|

4.8

|

21.7

|

12.8

|

45.8

|

-18.1

|

||||

| 1924

|

31.1

|

31.1

|

|

|

|

|

40.2

|

-9.1

|

||||

Table 2: General outlook on state expenses and resources, 1911-1924, in billion French francs[7]

Caption: (a) Banque de France and Banque de l’Algérie; (b) rentes and Crédit national included. These figures are a best-guess: many expenses were reported from one year to the other, and the global matching between expenses and resources was extended over several years thanks to Treasury special accounts and operations and various bank advances and short-term loans, most of which do not appear here. It is not even possible to arithmetically balance resources and expenses over several years because of the biases introduced by the war and post-war inflation.

Another “liability” was the Banque de France (BDF). Its metallic reserve was by far the world’s largest, although it still contained a large proportion of silver, and its ability to circulate a large number of banknotes under the inconvertibility regime had been fully demonstrated between 1870 and 1878.[8] This huge “war chest” was supplemented by the also very large gold and silver circulation and hoardings in France, also the world’s largest.[9] Consequently, the BDF had been at the heart of war planning in three different directions. First, innovative credit provisions had been designed to fund credit-based supply stocks in military strongholds through discount (revolving-credit) mechanisms. Second, the 3 July 1877 law, a clear by-product of the Franco-Prussian war, allowed requisitions (of animals, vehicles and so on) to be paid for by Treasury bonds, a provision partially enforced from August 1914 to January 1915, when full monetary payments were resumed.[10] Third, secret provisions between the state (Treasury) and the BDF had been negotiated in 1890 and renewed every six months.[11] A longer-term convention was negotiated in the aftermath of the 1911 crisis to provide 2.9 billion francs in short-term credits to the state in case of a war outbreak, and to circulate low-denomination banknotes to make for the eventual vanishing of fine silver and gold coins from circulation.[12] As Bernard Serrigny wrote, doubtlessly echoing contemporary beliefs: “This power of the Banque constitutes our true war chest,”[13] echoing the inaugural speech of Georges Pallain (1847-1923) as the BDF’s governor, 4 January 1898: “in case of national alarm, [the BDF is] the supreme guarantee of the patria’s salvation.”[14]

Contrary to Norman Angell’s idea that a general war was economically impossible because the economy rested on trust-dependent credit,[15] some contemporary authors concluded the opposite. Serrigny thus wrote in 1909, about a French-German war to come, that “the fight as organized by the two opponents is economically and socially possible, but at the price of enormous sacrifices during the conflict and of very real sufferings after peace is concluded.”[16] But the author also tried to show, drawing from the 1871 German example, that an economically developed country would draw no economic profit from territorial gains. Thus, war, while becoming costlier, had to aim at other goals than wealth – an outcome that was overlooked before and during the conflict. Looking at the different ways to fund the war, Serrigny also correctly foresaw that taxes would not be up to the task. To most, the solution laid in debt flotation, both at home and abroad, but inflation played a key role.

War finance: from principles to expedients↑

The Treasury expenses between 1914 and 1919 (demobilization year) were above 200 billion francs (in nominal value) i.e. about twice the nominal value of the 1913 GDP and about six times the amount of total Treasury expenses in normal times. They were mainly military in nature. And this does not even account for war-related post-1919 expenses (see Table 2). The breakdown of Treasury receipts clearly reveals the perilous wartime experience of French finance.

The failure to raise taxes↑

When war broke out, fiscal reforms had already been implemented in relation to military expenses: taxation on financial assets was a key political issue in 1913-1914 and again during and after the war, the reason for several cabinet resignations. It was related to the income tax issue, fiercely debated in the years preceding the war, a measure finally adopted 15 July 1914. During the debates, few had failed to note that it had been adopted in the UK in 1798 to pay for the French wars. This most important fiscal innovation had to be implemented in a country at war, and thus came to play an important role only in the following years, as is apparent in Table 3. Indeed, as a percentage of all fiscal resources, the growth of income tax, that was first implemented to a very limited scale in 1916 and came to fruition in 1917, barely compensated the decrease of the “four old women” (namely, the taxes on real estate, taxes on movable property, patent (professional tax) and taxes on doors and windows). This means that the bulk of the fiscal effort came through new exceptional taxations – i.e. exceptional indirect taxes and war profits taxation.

| 1893 | 1903 | 1913 | 1914 | 1915 | 1916 | 1917 | 1918 | 1919 | 1920 | 1921 | |

| Direct taxes (a) | 497 | 542 | 647 | 658 | 553 | 579 | 625 | 362 | 361 | 289 | 551 |

| Indirect Taxes (b) | 2,000 | 2,061 | 2,889 | 2,293 | 2,260 | |

3,650 | 3,753 | 6,286 | 9,557 | 10,607 |

| Monopolies (c) | 632 | 798 | 1,035 | 931 | 852 | 943 | 1,109 | 1,154 | 1,631 | 2,502 | 1,711 |

| State property | 42 | 51 | 62 | 124 | 186 | 240 | |

284 | 100 | 144 | 113 |

| Income Tax | 33 | 201 | 513 | 869 | 712 | 1,645 | |||||

| War Profits Tax | 634 | 1,780 | 1,725 | 2,937 | 3,169 | ||||||

| Other and sundry | 197 | 216 | 470 | N/A | 466 | N/A | N/A | N/A | 1,543 | 2,240 | 2,898 |

| Total | 3,368 | 3,668 | 5,103 | 4,006 | 4,317 | 4,738 | 6,473 | 7,846 | 12,515 | 18,381 | 20,694 |

Table 3: Fiscal resources, in million French francs[17]

Caption: (a) the “four old women” (taxes on real estate, taxes on movable property, patent (professional tax), taxes on doors and windows,) and assimilated; (b) Registration, stamps, excise, customs, etc.; (c) Post office, matches, tobacco, powder, telephone and telegraph, etc. As indicated for Table 2, these figures must be taken cum grano salis.

The war profits taxation (extraordinary tax on supplementary war profits), though, did not aim only at raising the state’s revenues: it also was associated with the distribution of sacrifices among the population as well as a “moralizing” tax. It is a rare case of an important fiscal measure that was adopted by a unanimous Parliament, in face of growing public discontent against war profiteers. Its impact was important both from the point of view of state finances and of its redistributive effects. Albeit a complex system of annual and delayed payments, the taxes collected between 1916 and 1921 amounted to about 10 percent of French GDP; the unanticipated result of the failure to take inflation into account.[18] Nevertheless, taxes fell short of financing even the civil expenses between 1914 and 1922. War expenses had to be funded otherwise.

Debts: the orthodox way↑

Loans are a natural way to finance an exceptional event that exceeds normal receipts (or even reduce them) and that may be amortized on a longer period than the annual budget. But resorting to debt means also finding ways to please the savers and investors. There are three conditions for that: propose a high enough rate of return; offer a sound repayment guarantee; organize a securities market that allows easy liquidation. But as the war wore on, a fourth condition developed: the unit of value stability. It was thus a crucial circumstance for the success of French public loans that exchange rates were stabilized during the war, thanks to UK and US policy, although France developed a growing commercial deficit, especially with neutral countries and the United States. From 1915 to 1920, six loans were floated (Table 4).

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||

| |

|

|

|

||||||||

| National Defence | 25/11/1915 | 87.25

|

88.00

|

5

|

5.73

|

15,205

|

13,307,812

|

2,244

|

3,181

|

1,598

|

6,285

(47%)

|

| National Defence | 5/10/1916 | 87.50

|

88.75

|

5

|

5.71

|

11,514

|

10,082,453

|

3,693

|

956

|

8

|

5,425

(54%)

|

| National Defence | 26/11/1917 | 68.60

|

69.20

|

4

|

5.83

|

14,882

|

10,209,073

|

4,580

|

449

|

6

|

5,174

|

| National Defence | 20/10/1918 | 70.80

|

71.70

|

4

|

5.65

|

31,303

|

22,163,223

|

13,255

|

1,412

|

250

|

7,246

(33%)

|

| War Period Total | 72,904

|

55,762,560

|

23,772

|

5,998

|

1,862

|

24,130

(43%)

|

|||||

| Redeemable | 19/2/1920 | 100.00

|

101.00

|

5

|

5.75

|

15,941

|

15,940,678

|

8,226

|

612

|

67

|

7,035

(44%)

|

| Loan of 1920 | 20/10/1920 | 100.00

|

101.15

|

6

|

6.00

|

28,088

|

28,088,861

|

4,136

|

354

|

12,320

|

11,278

(40%)

|

| Post-War Period Total | 44,029

|

44,029,539

|

12,362

|

966

|

12,387

|

18,313

(42%)

|

|||||

| 3,5% Loan of 1914 | 7/7/1914 | 3.5

|

3.85

|

805

|

732

|

||||||

| Grand Total | 117,737

|

100,522

|

36,134

|

6,964

|

14,249

|

42,443

|

|||||

Table 4: Permanent War Loans (emprunts), 1915-1921, in million francs (unless specified)[19]

Caption: Price 1: price for full cash payment; Price 2: price for instalments payment; Yield calculated on cash payment. Modes of payment: 1: Paid in National Defence Treasury Bills (Bons de la Défense Nationale). 2: Paid in National Defence Bonds (Obligations de la Défense Nationale). 3: Paid in old Rentes etc. 4: Paid in cash (share of money value in cash, in percent). The “money value” column gives the gross receipt of the loan (neat value = gross value minus 1+2+3) and is in thousand francs. Yields are indicative.

As the table demonstrates, the proportion paid in cash declined steadily during the war, meaning that savers and investors were swapping debts, further reducing the net resources of the Treasury. Besides, the lowering in interest rate from 1915-1916 to 1917-1918 appears as purely nominal: since the securities were offered well below par, the actual yield was much higher. In sum, albeit vigorous propaganda,[20] interest rates rose and French investors swapped shorter-term lower-yield bonds for longer-term higher yields securities.

The second orthodox route to debt is to tap into foreign capital, a move the government would have resisted before the war, but which appeared to be necessary as soon as it broke out. The first reason was that the war provoked an immediate freezing of the international payments system operated in London: it was thus crucial to find resources directly in the supplying countries. Second, the sudden occupational shift of the population and the loss of ten of the most productive departments to the German forces led to a dramatic decline in output that had to be compensated for through imports, on an unprecedented scale. As soon as August 1914, loans proposals were made in the US, but the US government refused that JP Morgan lend to France. The British government stepped in and in the spring of 1915, the US government authorized France to float loans on Wall Street. From then on, foreign loans escalated, financed by massive foreign assets sales, while French gold was largely retained in France. Nevertheless, in the spring of 1917, French saleable assets were running short, and the US stepped into the alliance just in time to supplement declining private sources of funds (Table 5).

Henceforth, allied states’ loans clearly dominated and, after the war, France never found such a ready access to foreign markets as she had experienced in the wake of both 1815 and 1871 defeats, but relied on the strong relationship built with a few prominent banks, most notably JP Morgan. Indeed, foreign debt had become a handicap to any sound financial policy. By its sheer size it represented a permanent menace on the French franc exchange rate while exacting a huge cost on public finances, which forced the state to resort to unorthodox methods to fund its budget: money supply was centre stage.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| 31/7 1914 | 31/12 1921 | ||||||||||

| Funded Debt | |||||||||||

| Perpetual | 21,922

|

32,889

|

43,608

|

51,278

|

91,988

|

88,366

|

102,073

|

100,438

|

656

|

4,587

|

|

| Term | 10,658

|

11,384

|

11,139

|

11,172

|

11,188

|

6,378

|

33,307

|

43,793

|

292

|

2,638

|

|

| Total Funded Debt | 32,580

|

32,800

|

|

|

62,450

|

103,176

|

104,744

|

135,380

|

144,231

|

948

|

7,225

|

| Annual Increase | 220.00

|

11,473

|

10,474

|

7,703

|

40,726

|

1,568

|

30,636

|

8,851

|

|||

| Floating Debt | |||||||||||

| Bank of France | 3,900

|

5,000

|

7,500

|

12,500

|

17,150

|

25,600

|

26,600

|

24,600

|

738

|

||

| Bank of Algeria | 75

|

25

|

85

|

215

|

235

|

||||||

| Total Bank Loans | 3,900

|

5,075

|

7,525

|

12,585

|

17,365

|

25,835

|

26,600

|

24,600

|

738

|

||

| Annual Increase | 1,175

|

2,450

|

5,060

|

4,780

|

8,470

|

765

|

-2,000

|

||||

| Treasury Bills | 427

|

2,046

|

7,006

|

12,618

|

19,551

|

22,918

|

47,934

|

51,191

|

60,362

|

3,978

|

|

| Other | 1,181

|

752

|

140

|

171

|

211

|

504

|

1,639

|

1,880

|

2,987

|

99

|

|

| Total Treasury | 1,608

|

2,798

|

7,146

|

12,789

|

19,762

|

23,422

|

49,573

|

53,071

|

63,349

|

|

|

| Annual Increase | 1,190

|

4,348

|

5,643

|

6,973

|

3,660

|

26,151

|

3,498

|

10,278

|

|||

| Total Floating Debt | 1,608

|

6,698

|

12,221

|

20,314

|

32,347

|

40,787

|

75,408

|

79,671

|

87,949

|

18

|

4,815

|

| Total Internal Debt | 34,188

|

39,498

|

56,494

|

75,061

|

94,797

|

143,963

|

180,152

|

215,051

|

232,180

|

966

|

2,040

|

| Foreign Debt | |||||||||||

| USA Nation | 5,853

|

10,489

|

16,500

|

16,500

|

17,356

|

||||||

| USA Market | 207

|

400

|

2,323

|

3,330

|

3,064

|

1,929

|

1,246

|

1,190

|

56

|

||

| Total USA | |

400

|

2,323

|

9,183

|

13,553

|

18,429

|

17,746

|

18,546

|

56

|

||

| UK Nation | 726

|

3,354

|

7,897

|

10,594

|

11,463

|

11,979

|

14,279

|

||||

| UK Market | 303

|

845

|

1,766

|

2,127

|

1,891

|

2,147

|

1,930

|

1,728

|

01

|

||

| Total UK | |

1,571

|

5,120

|

10,024

|

12,485

|

13,610

|

13,909

|

16,007

|

01

|

||

| Other | 196

|

1,452

|

1,541

|

1,215

|

1,010

|

60

|

|||||

| Total Foreign Debt | 510

|

1,971

|

7,443

|

19,403

|

27,490

|

33,580

|

32,870

|

35,563

|

317

|

||

| Annual Increase | 1,461

|

5,472

|

11,960

|

8,087

|

6,090

|

-710

|

2,693

|

||||

| Grand Total | 34,188

|

40,008

|

58 465 | 82,504

|

114,200

|

171,453

|

213,732

|

247,921

|

267,743

|

966

|

12,357

|

| Annual Increase | 18,457

|

24,039

|

31,696

|

57,253

|

42,279

|

34,189

|

19,822

|

||||

Table 5: French national debt, million French francs, as of 31 December (unless specified)[21]

Caption: Foreign debt at historical value.

The monetary resource↑

As is shown in Table 2, long-term debts and fiscal resources could not meet the level of expenses necessitated by a total war over four years long. The difference was paid for by printing money and short-term debt – i.e. monetary resources – that led to inflation. The phenomenon was completely new, since it never took the accelerating pace of previous monetary crises (1719-1720, 1792-1797) leading to a final crash, but was kept in check by state controls, a circuit policy[22] and an enduring – if shaken – trust of the French people in their currency. Thus, money supply and prices increased about four-fold during the war, and 25 percent more during the post-war era, leading to Poincaré’s stabilization of the franc in 1928 at 20 percent of its pre-war value in gold.[23]

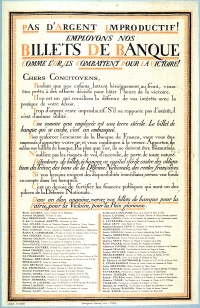

This resource came in three forms: first, a transitory one, was the use of Treasury notes to pay for military supplies, a very inconvenient payment system that was discontinued early in 1915; second, a very durable one that became a key political issue: the “advances” (renewable short-term loans) by the Banque de France and the Banque de l’Algérie (Tables 2 and 5); and third, the development of a floating debt, i.e. a short-term debt (three months to one year maturity) that became a natural outlet for the liquidity in excess within the French economy. The floating debt was transformed in a propaganda tool by the cunning name change that came in September 1914, which transformed overnight the Treasury Bonds in National Defence Bonds. The success was such that small denominations – as small as 5 and 20 FF – were decided in 1915, and a shorter maturity, one month, was introduced in April 1918. Thus, this short-term debt was essentially a roll-over debt that could be only partially consolidated into the annual perpetual flotation and necessitated enough public trust to have them redeemed and reissued at each fixed maturity.[24]

Conclusion: The post-war overhang: money, debts and reparations↑

| |

|

|

|

| 1914

|

40

|

55

|

5

|

| 1915

|

18

|

40

|

42

|

| 1916

|

14

|

43

|

43

|

| 1917

|

15

|

43

|

42

|

| 1918

|

15

|

48

|

37

|

| 1919

|

18

|

54

|

29

|

Table 6: Breakout of war finance resources[25]

It remains common to read that taxes financed 4 percent of French war expenses,[26] a good reason why inflation was untameable after the war. However the way this figure is calculated is problematic. Bertrand Blancheton, concentrating on 1914-1918, found that taxes accounted for 15 percent of public expenses, a close call to Georges Henri Soutou’s at 14 percent.[27] Secondary sources (Table 6) give comparable figures that considerably reduce the discrepancy between France and other warring countries. Nevertheless, this does not mean that the conflict did not entail large and enduring consequences on French finance. Three of them, among many, are outstanding and show that, in many respects, the French financial situation resembled more that of Germany than that of the UK.

First, the war proved very detrimental to the Paris financial market: it never recovered its former glory – it was even overtaken in quantitative terms by Amsterdam during most of the interwar period – but its relative decline reinforced the relative weight of the banking sector to the market finance sector, a trait that endured until today.[28] The birth of new banks, especially semi-public banks, during or immediately after the war (Crédit national,[29] BNFCE and Crédit populaire) reinforced that shift towards bank-based finance.

Second, the war was instrumental in the development of banking accounts in the French population. This stemmed first from the “circuit policy”, designed to sterilize excesses in the money supply in order to reduce the inflationary gap, a policy that was also furthered by the 1917 creation of “Chèques postaux” (Postal bank current accounts) and the payment of war pensions and damage reparations by checks. Thus, the monetary patterns strongly evolved, with the vanishing of gold and silver coins, and the growing use of banknotes and deposit money.

Third, monetary finance proved very durable. After the large debt issues of 1919 to 1924, the Crédit national had to rely, to pay for the war damages indemnities, upon the Treasury resources, which themselves were very much related to the BDF’s advances and the floating debt. Such large money issuance explains how France repaid its large internal debt: through inflation. From 1914 to 1919, prices had been multiplied by 3.6 to four, and in 1926, by about five,[30] i.e. the devaluation factor adopted by the 26 June 1928 stabilization law creating the new gold-based “Franc Poincaré”. These lessons of inflation-financed and erased debt were not to be lost a decade later.

Patrice Baubeau, Université Paris Ouest Nanterre / Institutions et dynamiques historiques de l'économie et de la Société

Section Editor: Nicolas Beaupré

Notes

- ↑ Durevall, Dick / Henrekson, Magnus: The Futile Quest for a Grand Explanation of Long-Run Government Expenditure, Journal of Public Economics, August 2011, volume 95(7-8), pp. 708-722. The question of a Wagner’s Law explanation of the growth of French public expenses has also been refuted by Delorme, Robert / Delorme, Christine: L’Etat et l’économie, Un essai d’explication de l’évolution des dépenses publiques en France (1870-1980), Paris 1983.

- ↑ See synthetic table in Occhino,Filippo / Oosterlinck, Kim / White, Eugene: How much can a victor force the vanquished to pay? France under the Nazi boot, Journal of Economic History, 68/1 (2008), table 2, p. 8.

- ↑ Fisk, Harvey Edward: French Public Finance in the Great War and Today: With Chapters on Banking and Currency, New York et al. 1922, p. 2. Both Japan and the Boer wars are deducted and colonial expenses included. Percentages may not add to 100 due to rounding.

- ↑ Truchy, Henri: Les finances de guerre de la France. Paris et al., 1926, p. 1.

- ↑ Girault, René: Place et rôle des échanges extérieurs, in Braudel, Fernaud / Labrousse, Ernest (eds): Histoire économique et sociale de la France, volume IV.1-2. Paris 1980, table p. 238.

- ↑ Serrigny, Bernard: Les conséquences économiques et sociales de la prochaine guerre: d'après les enseignements des campagnes de 1870-71 et de 1904-05, préface de Frédéric Passy, Paris 1909, p. 100.

- ↑ Fisk, French Public Finance in the Great War and Today 1922; Truchy, Henri: Les finances de guerre de la France, Paris et al. 1926; Germain-Martin, Louis: Les finances publiques de la France et la fortune privée (1914-1925), Paris 1925, p. 444.

- ↑ The 12 August 1870 law had two distinct provisions, the first one giving legal tender to Banque de France’s banknotes, and the second suspending banknotes convertibility into precious metals. The law of 1875 that planned the return to convertibility maintained the legal tender regime.

- ↑ Alphonse de Rothschild, in 1896. See Vignat, Régine: La Banque de France et l’Etat (1897-1920): la politique du gouverneur Pallain, unpublished PhD dissertation, December 2001, Nanterre University, 3 volumes, p. 813.

- ↑ Truchy, Les Finances de Guerre 1926, pp. 64-65.

- ↑ Vignat, La Banque de France, p. 146.

- ↑ Conventions du 11 novembre 1911 and secret addendum, Banque de France archives.

- ↑ Serrigny, Les conséquences, p. 119.

- ↑ Vignat, La Banque de France, p. 181.

- ↑ Angell, Norman: The Great Illusion, translated into French: La Grande Illusion. Paris 1910, pp. XX-331.

- ↑ Serrigny, Les conséquences, p. 11.

- ↑ Fisk, French Public Finance in the Great War and Today 1922, pp. 185-186.

- ↑ Hautcœur, Pierre-Cyrille: Taxation and the measurement of corporate profits. The case of the 1916 tax on war profits, working paper, PSE, May 2005.

- ↑ Fisk, French Public Finance in the Great War and Today 1922, p. 18 and Germain-Martin, Ibid., p. 179.

- ↑ di Jorio, Irène / Oosterlinck, Kim / Pouillard, Véronique: Advertising, Propaganda and War Finance: France and the US during WWI, working paper, 2006, p. 53.

- ↑ Fisk, French Public Finance in the Great War and Today 1922, pp. 26-28.

- ↑ Circuit policy: a financial policy that aims at financing the state through monetary issuance while preventing the inflationary impact of this issuance by funneling the extra money towards public debt. When the circuit is "closed", which is never perfectly achieved, all issued money comes back to the Treasury through bills and bonds net purchases. Such a policy implies some measure of financial repression: prices control, exchange rates control, foreign trade restrictions, etc.

- ↑ Blancheton, Bertrand: Le Pape et l’Empereur. La Banque de France, la direction du Trésor et la politique monétaire de la France (1914-1928), Paris 2001.

- ↑ Germain-Martin, Louis: Les finances publiques de la France et la fortune privée (1914-1925), Paris 1925, p. 150.

- ↑ Truchy, Les finances de guerre de la France 1926.

- ↑ Occhino / Oosterlinck /White, How much can a victor?

- ↑ Soutou, Georges-Henri: Comment a été financée la guerre”, in de La Gorce, Paul-Marie: La Première Guerre mondiale, volume 1, Paris 1991, p. 284.

- ↑ Baubeau, Patrice / Ögren, Anders: "Determinants of National Financial Systems: the role of historical events," in Baubeau, Patrice / Ögren, Anders (eds): Convergence and Divergence of National Financial Systems: Evidence from the Gold Standards, 1871-1971, London 2010, pp. 127-143.

- ↑ The Crédit national pour la réparation des dommages causés par la guerre (National credit for the repair of war-caused damages) is a state-controlled but publicly traded joint-stock bank created 1919. See Baubeau, Patrice et al.: Le Crédit national, Histoire publique d’une société privée, Paris 1994.

- ↑ Ibid.

Selected Bibliography

- Braudel, Fernand / Labrousse, Ernest (eds.): Histoire economique et sociale de la France, part 1-2, volume 4, Paris 1980: Presses universitaires de France.

- Delorme, Robert / Andre, Christine: L'etat et l'economie. Un essai d'explication de l'evolution des depenses publiques en France (1870-1980), Paris 1983: Éditions du Seuil.

- Durevall, D. / Henrekson, M.: The futile quest for a grand explanation of long-run government expenditure, in: Journal of Public Economics 95/7-8, 2011, pp. 708-722

- Fisk, Harvey Edward: French public finance in the great war and to-day, with chapters on banking and currency, New York; Paris 1922: Bankers Trust Co.

- Fridenson, Patrick: 1914-1918. L'autre front, Paris 1977: Editions Ouvrières.

- Hautcœur, Pierre-Cyrille: Was the Great War a watershed? The economics of World War 1 in France, in: Broadberry, Stephen N. / Harrison, Mark (eds.): The economics of World War I, Cambridge; New York 2005: Cambridge University Press, pp. 169-205.

- Lachapelle, Georges: Nos finances pendant la guerre; la gestion des finances publiques, les sociétés de crédit, la Bourse de Paris, la Banque de France, Paris 1915: A. Colin.

- Martin, Germain-Louis: Les Finances publiques de la France et la fortune privée (1914-25), Paris 1925: Payot.

- Occhino, Filippo; Oosterlinck, Kim; White, Eugene N.: How much can a victor force the vanquished to pay? France under the Nazi boot, in: The Journal of Economic History 68/1, 2008, pp. 1-45.

- Petit, Lucien: Histoire des finances extérieures de la France pendant la Guerre 1914-1919, Paris 1929: Payot.

- Serrigny, Bernard: Les conséquences économiques et sociales de la prochaine guerre. D'après les enseignements des campagnes de 1870-71 et de 1904-05, Paris 1909: V. Giard & E. Brière.

- Soutou, Georges-Henri: Comment a été financée la guerre, in: La Gorce, Paul Marie de (ed.): La Première guerre mondiale, Paris 1991: Flammarion, pp. 281-297.

- Truchy, Henri: Les finances de guerre de la France, Paris; New Haven 1926: Les Presses universitaires de France; Yale University Press.

- Vignat, Régine: La Banque de France et l'état (1897 - 1920), Paris Nanterre 2001: Université de Paris-Nanterre.