Introduction↑

The Belgian monetary system underwent important changes during World War I: the Société Générale, the biggest private bank in Belgium, took over as issuing house in place of the National Bank. Both German soldiers and the German administration used Marks in Belgium. Moreover, a range of German and Austro-Hungarian institutions and offices bought goods that were no longer available in their respective home countries. Some local Belgian authorities had printed their own emergency money to cope with the lack of means of payment in the beginning of the war. As a consequence, the monetary mass increased, while production decreased. This generated inflation.

The changes in the monetary system were initiated by the occupier: the Germans wanted to make Belgium, the occupied country, pay for the cost of the war. Therefore, when it became clear that the war would not be a short, swift operation, Belgian provinces were charged with war contributions, which were in reality paid by the issuing department of the Société Générale. The war not only created monetary instability, which was not resolved until 1926, but also impacted the relationship between the Société Générale, which positioned itself as a pillar of Belgian patriotism, and the National Bank.

Existing Research↑

The monetary history of the First World War was researched in the 1930s and 1940s as part of broader studies covering a longer time span.[1] The monetary situation during World War I had a prominent place in studies on the history of Belgium’s banks and also in a book on the Belgian franc.[2] André Hardewyn analyzed the German administration’s attempts to reform the obsolete Belgian taxation system in order to extract more from the occupied territory.[3]

This research takes a Belgian, as opposed to German, perspective of Belgian wartime finances. Reinhold Zilch recounted the history of the Belgian monetary system during the Great War in light of Germany’s war financing policy. His book was based on detailed archival research in Belgium and abroad and linked the monetary policy in Belgium to Germany’s difficulty financing its war. In short, the occupier was the prime actor. Zilch devoted much attention to German negotiations with Belgian actors, explaining that the German policy was based on the expectation of a short war. Germany would quickly win and vanquished states, such as Belgium, would have to pay reparations to Germany. Since the war lasted longer than expected, massive sums were needed to finance the war effort, which in turn threatened to destabilize the German monetary system. Therefore, the occupied territories had to pay war contributions. The aim of the Belgian monetary reforms was to create a mechanism to pay war contributions without harming the German monetary system.[4]

The Pre-war Belgian Monetary and Financial System↑

Belgium’s National Bank was founded in 1850. From a legal point of view, the bank was a private company with public functions: it served as exchequer and Belgium’s issuing house. The bank had offices in all the main cities and acted both as discount house and lender of last resort. It kept the Belgian gold reserve, which together with silver guaranteed the banknotes. In addition to the National Bank, big private Brussels-based banks formed the pillars of the financial system. These mixed banks were actively involved in industry both in Belgium and abroad (China, Russia, the colony of Congo). The Société Générale was the most important and was well integrated in international financial networks. The Caisse Générale d’Epargne et de Retraite (CGER), a state saving bank established in 1865, collected small savers’ deposits. Saving banks of the labour and peasant movements emerged in the late 19th century.[5]

The Monetary Chaos of the Invasion↑

In July/August 1914 a financial crisis broke out. Stockholders wanted cash, which resulted in a bank run. The Brussels and Antwerp stock exchanges closed their doors on 27 July 1914. As a result of this financial panic people lost faith in banknotes and wanted to exchange them for coins, causing a run on National Bank branches beginning in late July 1914. At the same time, the National Bank had to cope with an increasing demand for banknotes to fulfill the needs of private banks, which were confronted with clients who withdrew their money.[6] The public preferred coins over banknotes and hoarded them, leading to a lack of means of payment. Some local authorities responded by creating emergency money.[7]

Both the private sector and the state took measures to stop the bank run. The private banks in Brussels organized themselves into a consortium, a kind of mutual help to avoid one or more banks being forced to close its doors. The consortium, which existed throughout the war, was presided over by the Société Générale governor, underlining the bank’s leading role.[8] The government imposed the exchange rate for the banknotes, which could no longer be exchanged for gold or silver and had to be accepted as a legal means of payment. Bank deposits were blocked. Although these measures put an end to the bank run, the lack of ready money remained.[9]

The National Bank↑

A key issue for the monetary policy was the position of the National Bank. From the beginning of the invasion, the German military conflicted with the Belgian central bank. Invading troops seized money from the Hasselt and Liège branches and forced the Liège director to sign the banknotes in order to use them to buy or confiscate a range of goods for their troops. This behaviour was inspired by the German doctrine that the enemy had to pay for the war. To a certain extent, this confiscation could be based on the Hague Convention, with one important exception: private property could not be violated. From a legal point of view, the National Bank was a private company, but the Germans argued that the bank had a public function and therefore the indefeasibility of private property did not apply either to the bank’s money or its banknotes. The National Bank ordered the branch directors to hide or even destroy their money. Money from the central office in Brussels was moved to Antwerp and later to Ostend, including the finished but unsigned banknotes, CGER money and the currency printing blocks. By the end of September 1914 all of this material and the bank’s reserves, including its gold, had been transferred to the Bank of England in London.

Once it was clear that the war would continue, the Germans had to acknowledge a lack of money, needed for the troop provisions and military operations. Printing new banknotes was impossible. The Belgian population did not readily accept German Marks for political as well as economic reasons (an overrated forced exchange rate of 1.25 BEF) and the use of Marks was a burden for the Reichsbank. After Belgian occupation became a settled fact, it was decided that country’s economic activity should be stimulated to provide for German troops and ease social tensions. Belgium had to pay war contributions, for which banknotes were needed. The limited mode of exploitation became obvious in October 1914: local authorities were out of cash to cover the occupation costs and needed an advance from the National Bank. But the bank had stopped giving these advances in October 1914 to put an end to the plunder of the country. The outcome of the first Marne battle, which stopped the German advance, likely played a role too.

The National Bank also had to consider the needs of the Belgian population: a passive attitude of the National Bank hindered economic activity. The bank was exchequer and paid civil servants’ pensions and salaries. This explains why the bank finally reached an agreement with the German administration to open a special account for occupied territories’ public financial needs. Only the Belgian treasury could order payments and the occupying administration controlled the account. In return, the Germans promised not to confiscate bank property, including ready money. This agreement enabled the Germans to use the occupied territories’ income for expenses for the population or administration in accordance with the Hague Convention.

As far as the issuing of banknotes was concerned, the question was complicated by the fact that the gold and the blocks were not in the hands of the bank directors in Belgium. One director was also with the exiled government in Le Havre, which had declared that if necessary, the National Bank gold in London could be used to finance the war effort. Moreover a branch was opened in Le Havre. There was a risk that banknotes would be printed without taking the gold coverage rules into account, a situation which could lead to the dismissal of both directors and board in Belgium. A bank delegation therefore travelled to Le Havre and London to convince the Belgian government to transfer gold and the blocks back to Belgium. The proposal was rejected and as a result the National Bank could not issue banknotes for the rest of the war. The Germans also forbade the bank to issue further banknotes, but nonetheless needed an alternative to dispose of money to pay their war contributions. Different solutions were studied – there was no clear and unified vision – and negotiated together with the National Bank and the big private banks, especially the Société Générale. Once the option of creating Reichsbank branches in Belgium was rejected on political (this could be seen as the beginning of an annexation) as well as monetary (growth of the monetary mass leading to inflation) grounds, it was clear that a solution within the Belgian financial system framework had to be found. Since the National Bank was no longer an option, the private banking sector was the only alternative. Beginning in November 1914, private banks and politicians still in Belgium lobbied to give the right to issue banknotes to one of the private banks. A delegation of private bankers travelled to Le Havre to discuss this solution with the exiled government, which agreed and declared not to make use of the National Bank’s gold, banknotes or the printing blocks without the consent of the bank directors in occupied Belgium. The new issuing house would be obligated to finance Belgium’s war contribution to Germany.

The Société Générale as New Issuing House↑

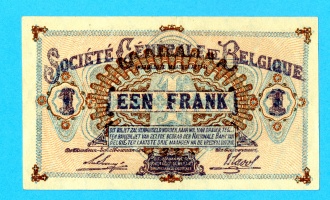

The Société Générale was awarded the right to print money. The bank had already played this role before the creation of the National Bank and had a network of branches and associated banks in the country. As leader of the banking consortium, the Société Générale had been heavily involved in decision-making on monetary policy and cooperated closely with the National Bank. Governor Jean Jadot (1862-1930) and director Émile Francqui (1863-1935) were involved in the negotiations to find a solution to the monetary problems. The journey to Le Havre was intended to secure political backing for the agreement with the National Bank to give the issuing privilege to the Société Générale. The Belgian financial world accepted this solution.

An additional department was established within the Société Générale to issue new banknotes. Since the department was a separate entity, the activities could be stopped at the armistice when the National Bank again assumed its role as issuing house. The Société Générale and the National Bank maintained close ties: the former wanted political backing while the latter wanted control over the department’s activities, since it would have to take over again after the war. In January 1915 the National Bank agreed to transfer its stock of German and other foreign currency to the Société Générale to cover the new banknotes. In return, the National Bank agreed to take over the department after the war including losses and profits. The National Bank continued its activities with the exception of discount and Lombard credit. The banknotes were produced in the National Bank’s printing establishment under the control of Reichsbank employees. The Germans accepted the close cooperation between the two banks, since it fostered trust in the new banknotes.[10]

Belgian War Contributions↑

For the Germans, the issuing house was not primarily a matter of maintaining economic activity in Belgium. They needed a solution for financing the war contributions. The Germans initially imposed a monthly contribution of 40 million BEF, raised to 50 million BEF in November 1916 and then in May 1917 to 60 million BEF. The total amounted to 2,280 million BEF, far exceeding Belgium’s pre-war tax income of 350 million BEF.[11] The nine provinces paid war contributions, a level of political decision-making that still worked normally and covered the whole territory with a limited number of interlocutors. The technique used to collect the contributions was the outcome of negotiations between the German administration and Belgian bank representatives. In fact, the provinces acted as intermediaries for the issuing department of the Société Générale. According to the mechanism developed in December 1914, the provinces paid the contributions with certificates issued for that purpose. The Société Générale took these certificates and paid the Germans with banknotes from its issuing department. The provinces’ certificates served as coverage for issuing banknotes in general. Some of the certificates were taken by the banks as the capital market expanded and banks disposed of the money to buy the certificates.[12] The public also bought certificates. Certain social groups such as farmers disposed of much cash.[13] Another backing for the banknotes was a special Société Générale account with the Reichsbank. The so-called ‘mass-products’ confiscated by the Germans were booked on this account. Payment would follow after the war but in the meantime the Société Générale bought the bonds. Since the material was destroyed in the war, this mechanism had an inflationary effect, which became clear in the total amount of banknotes issued by the Société Générale. In 1915 the total circulation of Société Générale’s banknotes amounted to 600 million BEF; in 1918 this had increased to 1,525 million BEF.

The National Bank banknotes were, with the exception of damaged copies, not withdrawn from circulation, but hoarded by the population following Gresham’s law that bad money drives good money out. Circulation decreased from 1,614 million BEF end 1914 to 1,250 million at the end of the war.[14]

| 1914 | 1,218 |

| 1915 | 1,805 |

| 1916 | 2,020 |

| 1917 | 2,241 |

| 1918 | 2,651 |

Table 1: The circulation of all Belgian banknotes shows the steady increase of monetary mass (in millions of BEF)[15]

The monetary circulation also increased due to the injection of German marks in the Belgian monetary system. German soldiers brought marks with them; marks were also used by the German administration to pay for goods before the Société Générale’s new issuing department began operations. As the war went on, marks were also used by a host of different offices and institutions in Germany and even in Austria-Hungary to buy products that had become scarce following the British blockade. Belgians wanted to be paid in cash rather than on an account. The estimates of the total amount of marks in Belgium on Armistice Day are between 2.4 and 6 billion marks, but four billion seems to be realistic.[16] This meant that there was much more German money than Belgian money in circulation, explaining the importance of the issue of the retreat and exchange of the German marks from the Belgian monetary system in post-war reconstruction. The Société Générale and the National Bank kept most of the marks since the Belgian population was not eager to have German money or use it to pay debts. The gold and foreign currency of the National Bank and the Société Générale that were transferred to Germany were paid with marks. In 1916 the level of gold coverage in the Reichsbank was critically low. The German administration put pressure on the National Bank and the Société Générale to transfer the marks to Germany and put them on a blocked account, which would be freed after the war at a fixed exchange rate of 1.25 BEF. Although the exchange rate was relatively favourable, the two banks rejected the proposal since it could be seen as a monetary annexation, but gave in after threatened with German sequestration: 1.5 billion marks were transferred to the Reichsbank. This decision had negative consequences: inflation was fuelled as banknote coverage decreased and for the Belgian public, assets in bank safes were no longer protected against German confiscation.

Conclusion: The Heritage of the War↑

There were two main financial consequences of the war for Belgium: the first related to inflation and the second institutional in nature. The new monetary system initiated by the Germans stimulated inflation in the Belgian economy. There were more banknotes circulating (conservative estimates point to a multiplication factor of 5.7),[17] which were not covered in the same way by gold or silver as before the war. This monetary expansion was one cause of the war inflation. Taking prices as an indicator for inflation, in 1918 the price level was four times higher than in 1913.[18] B. S. Chlepner gave a good summary of the link between the monetary situation and the ‘real’ economy. The fact that the public and the banks readily bought public bonds seemed to indicate that the country was rich. The opposite was true: the investment in bonds was not the product of savings but resulted from the fact that the country was taken from its stocks, material, production capacity and investment opportunities in industry, commerce and agriculture. All this was replaced by banknotes or public debts.[19]

Monetary reconstruction would become one of the central problems for post-war economic policy. The redesign of the banking world during the war also had political effects: the National Bank operated in the shadow of the Société Générale, which used the wartime turn of events to confirm its dominant position in the Belgian banking system and position itself as a pillar of Belgian patriotism by assuming the role of issuing house and supporting the National Committee for Aid and Food. This paved the way for the Société Générale’s post-war ‘national turn’, leading to conflicts over the National Bank’s role in the monetary system.

Dirk Luyten, Centre for Historical Research and Documentation on War and Contemporary Society and University of Ghent

Section Editor: Benoît Majerus

Notes

- ↑ Chlepner, B. S.: Le marché financier belge depuis cent ans, Brussels 1930; Baudhuin, Fernand: Histoire économuque de la Belgique. 1914-1939, 2 vol., Brussels 1946.

- ↑ Van der Wee, Herman/Tavernier, Karel: La Banque nationale de Belgique et l’histoire monétaire entre les deux guerres mondiales, Brussels 1975; Kurgan-Van Henternryk, Ginette: “De Société Générale van 1850 tot 1934” [“The Société Générale from 1850 to 1934”], in: Van der Wee, Herman (ed.): De Generale Bank. 1822-1997 [The General Bank. 1822-1997], Tielt 1997, pp. 69-203.

- ↑ Hardewyn, André: “Een ‘vergeten’ generale repetitie. De Duitse oorlogsbelastingen tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog” [“A ‘forgotten’ general rehearsal. The German war taxation in the First World War”], in: Cahiers d'Histoire du Temps Présent 6 (1999), pp. 183-210.

- ↑ Zilch, Reinhold: Okkupation und Währung im Ersten Weltkrieg. Die deutsche Besatzungspolitik in Belgien und Russisch-Polen, 1914-1918, Goldbach et al. 1994.

- ↑ Chlepner, Le marché 1930, pp. 72-112; De Belgische Spaarbanken. Geschiedenis, recht, economische functie [The Belgian Saving Banks : history, law, economic function], Tielt 1986.

- ↑ Chlepner, Le marché 1930, p. 113.

- ↑ Zilch, Okkupation 1994, p. 99.

- ↑ Kurgan-Van Hentenryk, De Société 1997, p. 186.

- ↑ Zilch, Okkupation 1994, p. 99.

- ↑ Zilch, Okkupation 1994, pp. 137-55.

- ↑ Baudhuin, Histoire 1946, vol. I pp. 41f.

- ↑ Zilch, Okkupation 1994, pp. 167-82.

- ↑ Chlepner, Le marché 1930, p. 114.

- ↑ Zilch, Okkupation 1994, p. 158.

- ↑ Janssens, Valery: De Belgische frank. Anderhalve eeuw geldgeschiedenis [The Belgian Frank : one century and a half history of money], Brussels 1976, p. 437.

- ↑ Zilch, Okkupation 1994, p. 212; Janssens, De Belgische 1976, p. 168; Baudhuin, Histoire 1946, vol. I p. 52.

- ↑ Janssens, De Belgische 1976, p. 168.

- ↑ Scholliers, Peter: Loonindexering en sociale vrede. Koopkracht en klassenstrijd in Belgie tijdens het interbellum [Wage index and social peace. Purchase power and class struggle in Belgium in the interwar period], Brussels 1985, p. 299.

- ↑ Chlepner, B. S.: Les finances, la monnaie et le marché financier, in: Mahaim, E. (ed.): La Belgique restaurée. Etude sociologique, Brussels 1926, pp. 393-504, p. 456.

Selected Bibliography

- Baudhuin, Fernand: Histoire économique de la Belgique, 1914-1939, 2 volumes, Brussels 1946: Etablissements Emile Bruylant.

- Chlepner, B. S.: Les finances, la monnaie et le marché financier, in: Mahaim, Ernest / Solvay, Ernest (eds.): La Belgique restaurée. Étude sociologique, Brussels 1926: M. Lamertin, pp. 393-504.

- Chlepner, B. S.: Le marché financier belge depuis cent ans, Brussels 1930: Falk fils.

- Hardewyn, André: Een 'vergeten' generale repetitie. De Duitse oorlogsbelastingen tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog (A 'forgotten' general rehearsal. The German war taxation in the First World War), in: Cahiers d'Histoire du Temps Présent/6 , 1999, pp. 183-210.

- Janssens, Valéry: De Belgische frank. Anderhalve eeuw geldgeschiedenis (The Belgian Frank. One century and a half history of money), Antwerpen, Amsterdam 1976: Standaard.

- Kurgan-Van Henternryk, Ginette: De Société Générale van 1850 tot 1934, in: van der Wee, Herman / Verbreyt, Monique / et al. (eds.): Die Generale Bank, 1822-1997. Eine ständige Herausforderung, Tielt 1997: Lannoo, pp. 69-203.

- Put, August Van (ed.): De Belgische spaarbanken. Geschiedenis, recht, economische functie (The Belgian saving banks. History, law, economic function), Tielt 1986: Lannoo.

- Scholliers, Peter, Centrum voor Hedendaagse Sociale Geschiedenis, Vrije Universiteit Brussel (ed.): Loonindexering en sociale vrede. Koopkracht en klassenstrijd in België tijdens het interbellum (Wage index and social peace. Purchase power and class struggle in Belgium in the interwar period), Brussels 1985.

- van der Wee, Herman / Tavernier, Karel: La Banque nationale de Belgique et l'histoire monétaire entre les deux guerres mondiales, Brussels 1975: Banque nationale de Belgique.

- Zilch, Reinhold: Okkupation und Währung im Ersten Weltkrieg. Die deutsche Besatzungspolitik in Belgien und Russisch-Polen 1914-1918, Goldbach 1994: Keip.