Introduction↑

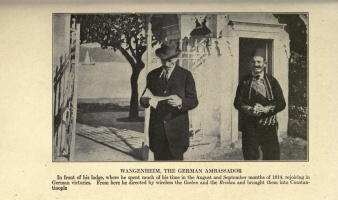

In order to form a general picture regarding the entry of the Ottoman Empire into the First World War, one must consider the actions and attitude of the German ambassador to the Ottoman capital, Baron Hans von Wangenheim (1859-1915).

The Peace Years, 1912-1914↑

Von Wangenheim became ambassador in October 1912, when German influence on the Ottoman government was diminished because of the German stance on the Albanian question and particularly because of Wilhelm II, German Emperor’s (1859-1941) positive attitude towards the relative Greek claims. From his arrival in Constantinople (Istanbul), von Wangenheim had to face the reservation and doubt of even the most prominent Germanophile among the leadership of the Young Turks, Enver Pasha (1881-1922).

With the arrival of the German military mission in the Ottoman capital in 1913, the Russian foreign minister, Sergev Sazonov (1860-1927), plainly accused the ambassador of demanding his dismissal. Nevertheless, the situation was truly different than perceived, as von Wangenheim’s involvement in the affair was not crucial. Moreover, von Wangenheim openly despised General Otto Liman von Sanders (1855-1929), having repeatedly asked the German government to relieve him of his duties. Furthermore, he was sympathetic to Russian claims about Constantinople and was open to the incorporation of the city and its surrounding area into the Russian Empire. Finally, it must be pointed out that the ambassador was in contact with and even helped Alexander Parvus (1867-1924), a Marxist activist and free agent, who showed signs of opportunism, to promote his plans to the German General Staff.

The Ottoman Empire enters the War↑

The Ottoman Empire was keen to secure an alliance with Germany and Austria-Hungary as a means of self-preservation, ensuring the expansion of the Ottoman territories and the protection of the empire from foreign territorial claims. However, before approaching the Germans, the Ottoman government persisted in establishing an alliance with Great Britain and France but found them unwilling. In this context, Enver Pasha, repeatedly tried to convince the German ambassador of the need for a German-Ottoman alliance, but von Wangenheim was strongly opposed. On the contrary, he was convinced that the Ottoman army was in a state of disarray and of no value, agreeing with the head of the German military mission in Constantinople, General von Sanders. Accordingly, in an official letter to Berlin on 18 July 1914 the German diplomat stated that in his opinion the Ottoman Empire was “undoubtedly still useless as an ally, being a burden to her allies and not offering them any advantage”[1]. Enver Pasha met the ambassador in secret on 22 July 1914, when his repeated offer for an alliance with Germany faced the staunch decline of von Wangenheim. However, the Kaiser’s view on the matter was completely different and he ordered the acceptance of the Ottoman offer, an act that led to the signing of a secret German-Ottoman alliance on 2 August 1914.

The Declaration of Holy War against the Allies↑

The Ottoman leadership appeared ready to use propaganda tactics and declared holy war (jihad) against the Allies, encouraged substantially by the Germans, thus capitalizing on the sultan’s role as caliph of Muslims globally. It was believed that in this way, native Muslims in the British and French colonial empires would rise up against their Christian rulers, but the results were disappointing. From the start, von Wangenheim opposed this scheme; he supported it only because of his loyalty to the Kaiser. Personally, he believed that in this way the Central Powers were in danger of alienating Italy, considering that its Muslim colonial subjects numbered in the millions. Furthermore, he was afraid of the spread of violence against the Ottoman Empire’s non-Muslim subjects. However, despite his oppositional thinking, the ambassador was actively involved in organizing guerrilla warfare and supporting and encouraging Islamic movements in the Russian provinces and in British-held Egypt in accordance with his country’s policy.

The Armenian Genocide↑

Because of the war, the so-called “Armenian question” reignited, ending with the Armenian genocide of 1915 by Ottoman authorities. Von Wangenheim believed that the Armenians did not pose a threat to the Ottoman state and that an Armenian rebellion was not at all imminent or feasible and that there were no such plans since 1908. Moreover, the German diplomat relayed a report to Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg (1856-1921), which was originally written by the German consul to Erzurum and suggested the existence of an Ottoman plan to provoke the Armenians into open rebellion. The diplomat was critical of Ottoman action against the Armenians and issued an official protest against their deportations on 4 July 1914.

However, the ambassador underestimated Ottoman plans regarding the Armenians and thus did not press the matter in his official correspondence with Berlin. It seems that he did not possess accurate information about the situation. In this context, the American ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, Henry Morgenthau (1856-1946), criticized von Wangenheim’s ambiguous attitude towards the genocide.

The scandal regarding the Armenian massacres, combined with the landings at Gallipoli, which he thought would succeed in reaching Constantinople, are recognized as the causes of the stress-provoked stroke that eventually killed him. The Austrian ambassador to the Ottoman capital attributed his colleague’s distress to the fact that he felt responsible for the entry of the Ottoman Empire into the war.

Christos Bouris, Independent Scholar

Section Editor: Pınar Üre

Notes

- ↑ Rogan, Eugene: The Fall of the Ottomans. The Great War in the Middle East, New York 2015, p. 40.

Selected Bibliography

- Aksakal, Mustafa: The Ottoman road to war in 1914. The Ottoman Empire and the First World War, Cambridge 2008: Cambridge University Press.

- Dadrian, Vahakn N: The Armenian question and the wartime fate of the Armenians as documented by the officials of the Ottoman Empire's world war I allies: Germany and Austria-Hungary, in: International Journal of Middle East Studies 341/1, 2002, pp. 59-84.

- Hosfeld, Rolf / Pschichholz, Christin (eds.): Das Deutsche Reich und der Völkermord an den Armeniern, Göttingen 2017: Wallstein Verlag.

- McMeekin, Sean: The Berlin-Baghdad express. The Ottoman Empire and Germany's bid for world power, Cambridge 2010: Harvard University Press.

- McMurray, Jonathan S.: Distant ties. Germany, the Ottoman Empire, and the construction of the Baghdad railway, Westport 2001: Praeger.

- Rogan, Eugene L.: The fall of the Ottomans. The Great War in the Middle East, New York 2015: Basic Books.