Introduction↑

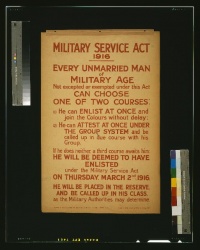

Britain had never before attempted to build and provide for an army of the size of the volunteer force which was rallied in the first sixteen months of the war. By 1916 it had become clear that the British government was ill-equipped to deal with the number of casualties returning from the Western Front. There was little provision to help ex-servicemen return to civilian life or to rehabilitate disabled men via training and employment. The new citizen army expected better care and, when the Military Service Act was passed in January 1916, the state was perceived to have assumed the role of caring for men who had served “King and Country,” although it took some time for the government to accept this responsibility. The Liberal MP James M. Hogge (1873-1928) was the driving force behind improving pay and conditions for men serving in the forces. He had already been instrumental in pushing for the Civil Liberties Act (1915) which stipulated that any debts incurred by servicemen whose army pay was below their civilian wage should be settled by the state. Using his advice column in the Edinburgh Evening News, Hogge went on to argue that the introduction of conscription invested the state with moral and legal obligations to care for servicemen on their return. Hogge also campaigned for ex-servicemen’s pensions. In January 1916 he declined a junior post in the newly established Ministry of Pensions and instead formed the Naval and Military War Pensions League. The aims of the League included eradicating inequalities in the granting and administration of war pensions, acting as a central point for the organisation of ex-servicemen and their dependents, and protecting and representing veterans’ interests in parliament. However, the League was not widely supported. Hogge’s radical politics, particularly his support for Scottish nationalism, had made him unpopular, as had his opposition to conscription and his open association with Conscientious Objectors. There were also concerns that veterans might mobilise themselves en masse and potentially become a threat to the social order.[1] Yet, by founding the Naval and Military War Pensions League, Hogge set the pattern for organised ex-servicemen’s activities.

Providing for Army Casualties↑

Throughout 1917 Hogge established new branches of the League across the United Kingdom. He maintained that veterans should not be regarded as charity cases who would be forced to rely on patchy local philanthropy and inadequate royal warrants and he continued to put pressure on the government in parliament. When members of the League demonstrated against the Military Service (Review of Exceptions) Act (1917), which planned to recall all men under the age of thirty-one even if they had already served and had been injured, a group of the League members from London’s East End established the National Federation of Discharged and Demobilised Sailors and Soldiers. They continued to oppose the Exceptions Act with the call of “every man once before any man twice.” Veterans’ pressure on the government increased further at the Abercromby constituency by-election in June 1917 when Frank Hughes, a disabled former private soldier, stood as a candidate for the National Federation of Discharged and Demobilised Sailors and Soldiers against Edward Stanely, Lord Stanley (1894-1938), the son of Edward Stanley, Lord Derby (1865-1948), the new Secretary of State for War. Although Hughes lost the election it forced the government to review the Exceptions Act. As a result of the inquiry the medical review boards and examinations were removed from the War Office and placed under the control of civilian committees. The Federation developed into a significant organisation, but concerns grew about the existence of concentrated groups of disgruntled ex-servicemen. Shortly after the Abercromby election, Lord Derby established a group called Comrades of the Great War with the support of parliament and the Army Council. As the Comrades sought to attract members and patrons from more privileged classes, it stood in opposition to the Federation and the Association, both of which had a more egalitarian outlook. While the former advocated a paternalistic approach to ex-servicemen, the latter groups wanted to address the issue of veterans’ rights and place their grievances before the public and parliament.

These developments attracted the attention of other public figures, most notably Horatio Bottomley (1860-1933), publisher of the populist national weekly John Bull, and the former naval officer and Independent MP Noel Pemberton-Billing (1881-1948). Bottomley had already antagonised the government and the War Office by publishing numerous criticisms of the neglect of British servicemen and their families. In 1917 he continued to publicise himself as “the servicemen’s friend,” printing articles critical of the Comrades which claimed that they were “the vehicles of a plot by privileged classes to undermine pressure tactics employed by the Federation.”[2] Bottomley approached Hogge with an offer of an annuity of £2,000 to the Federation, but the money was returned three months later when the working relationship between the two men ended acrimoniously. In 1917 Pemberton-Billing established the Vigilante Society, the declared aim of which was to raise moral standards in public life. He believed that the veterans’ movement was a powerful force which should be harnessed to improve British society and it was with this in mind that he founded the Silver Badge Party (SBP) in the summer of 1918. The outlook of the SBP was similar to that of the Vigilante Society: “conservative, imperialist and anti-semitic.”[3]

Suspicion and Surveillance↑

In the immediate post-war period, political activism of any type aroused government suspicions. Reflecting concerns that veterans’ groups were being infiltrated by enemies of the state, a range of potential dissidents – including German spies, Bolshevik sympathisers, Independent Labour Party members critical of the war effort, and anti-conscriptionists – were placed under surveillance by the Special Intelligence Branch of the Home Office in 1918. By the summer of 1918, the Association planned to field up to fifty candidates in the general election due to take place later that year. Only one of these candidates was voted into parliament, showing that the electorate preferred post-war unity over special interest parties.

However, after the Armistice, problems with demobilisation resulted in violent unrest and throughout 1919 there was a series of “Khaki Riots,” with the most serious disturbances occurring in June 1919. It was estimated that up to 300,000 veterans were receiving unemployment payments and, as David Lloyd George’s (1863-1945) plans to allow veterans to rent small farms failed, over 42,000 ex-servicemen emigrated to Canada and Australia. Widespread disillusionment among veterans acted as a catalyst for the founding of new groups. The Soldiers’, Sailor’s and Airmen’s Union, which advocated that men who had volunteered for service under the Derby Scheme should demobilise themselves by 11 May 1919, aligned themselves with the more radical fringe of the Federation to form the National Union of Ex-Servicemen (NUX), who wanted to join with the Labour Party and commit their organisation to social improvement for all sections of British society. An International Union of Ex-Servicemen (IUX) was formed by dissident Federation members in Glasgow and received support from political activists such as Sylvia Pankhurst (1882-1960) and the Scottish revolutionary John Maclean (1879-1923). The most radical of all the veterans’ groups, the aim of the IUX was to overthrow the capitalist system.

Division and Dissent↑

Post-Armistice organisations like the Soldiers’, Sailor’s and Airmen’s Union and the National Union of Ex-Servicemen felt that groups like the Federation, which were founded during the war, had not been effective in pressing for a new social order. There were also tensions within these organisations, particularly the Comrades, whose members began to challenge the authority of their executive in the spring of 1919. A demonstration for improved benefits for disabled servicemen in Hyde Park in May 1919 ended with a march towards Westminster where there were clashes with police. Grievances were passed to James Hogge, who warned parliament that the ex-servicemen were on the verge of anarchy. However, internal divisions within the groups continued to hamper the veterans’ cause. The NUX aligned with the Labour Party in December 1919, but the Socialists and Trade Unionists could not form an alliance because the Independent Labour Party had not supported the war effort which alienated many ex-servicemen. Fears over dilution also meant that relations between veterans and the trade unions would remain volatile throughout the 1920s.

In July 1919, the Federation, the NUX and the IUX boycotted the victory celebrations that marked the closing of the peace conferences and the formal end of the conflict. There were many instances of riots and arson attacks. Later that year the government made pensions a statutory right, instituted training programmes for the disabled and gave veterans preferential treatment at Labour Exchanges. Many ex-servicemen testified at a Select Committee on Pensions and the majority of their suggestions were accepted. By January 1920, when conscription in Britain ended, approximately 4 million men had been demobilised and of that number 90 percent were employed, leaving around 400,000 without work.[4]

But the British economy quickly began to stagnate as the post-war boom ended and financing ex-servicemen’s groups became problematic. The Officers’ Association was formed in 1920 by Earl Douglas Haig (1861-1928) and Countess Dorothy Maud Haig (1879-1939), Admiral of the Fleet David Beatty, Earl Beatty (1871-1936) and Marshal of the Royal Air Force Hugh Trenchard, Viscount Trenchard (1873-1956) and the city of London, to raise public subscriptions for former officers in need, but this merely added to the number of veterans’ groups, all of which were becoming increasingly isolated and struggled to keep their memberships active. After several months of negotiation, in the spring of 1921, the Association, the Comrades, the Federation and the Officers’ Association agreed to unite in order to form the British Legion. The IUX and NUX both declined to join and disbanded by the end of 1921.

The creation of the British Legion ended division and competition among ex-servicemen’s groups and the organisation became the single voice of British veterans. Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig was appointed its President, the Prince of Wales, later known as Edward VIII, King of Great Britain (1894-1972), became Patron, and a British Legion branch comprised of representatives from each political party was founded in the House of Commons. Haig desired that the creation of the British Legion would have a calming influence at a politically inflammatory time. By reproducing the camaraderie of the trenches he explained that the organisation would appeal to ex-servicemen who “realise the nobility of service, to enrol themselves to win the peace, even as they won the war.”[5] He admitted that “subversive tendencies are still at work” but that the concerns over potentially disruptive servicemen would be quelled by the Legion which would “foster the spirit of self-sacrifice which inspired servicemen to subordinate their individual welfare to the interests of the Commonwealth.”[6] Haig was determined to remain aloof from politics and that the Legion “should be Imperial and in no sense partisan.”[7] In its first year the membership of the British Legion numbered 18,106 and reached around 400,000 in 1938. Other new groups were founded, such as the Labour League of Ex-Servicemen (1927) and the Limbless Ex-Servicemen’s Association (1932), but none threatened the dominance of the British Legion which generally sought to avoid controversial domestic and foreign issues.

The British Legion and Remembrance in the Interwar Years↑

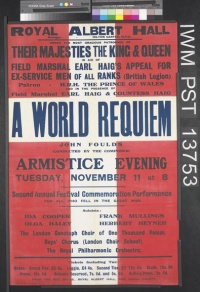

Once the wreath-laying and marching has finished, the national remembrance schedule concludes at the Royal Albert Hall with the British Legion’s “Festival of Remembrance.” The history of the Festival of Remembrance provides a fascinating insight into the debates over the ways in which the war was commemorated in the 1920s. The tradition of an annual concert on Armistice night began in 1921, the same year the British Legion began the mass production and sale of poppies. The first commemorative concert was staged at the Royal Albert Hall on Armistice Night 1923. It was organised by the Manchester-born cellist and composer John Foulds (1880-1939) and the musician Mary Maud MacCarthy (1882-1967). The centrepiece was Foulds’ World Requiem (Opus 60), which he had written from mid-1919 to April 1921. MacCarthy was an Irish-born professional violinist with links to prominent socialists and members of the Suffragette movement. The phrase “Festival of Commemoration” was first used by MacCarthy who was the driving force behind the Albert Hall Armistice Night concerts in the mid-1920s.

The World Requiem was the most ambitious composition Foulds would write in his career, both in terms of length and the unprecedented number of performers required. It was agreed that the royalties from the annual performances would be donated to the British Legion for an initial term of five years. The piece was intended to stand as a national musical monument to the dead of the First World War, with a presentation copy of the programme entitled, “A Cenotaph in Sound. In Memory 1914-18.” The citation in the score reads, “A tribute to the memory of the Dead – a message of consolation to the bereaved of all countries.” With a running length of approximately two hours, the World Requiem was written for 1,200 singers and instrumentalists. The piece used texts from multiple literary sources, including the Bible, Pilgrim’s Progress, Hindu poetry and some contemporary free verse.

The first performance in 1923 was attended by the George V, King of Great Britain (1865-1936) and Mary, Consort of George V, King of Great Britain (1867-1953), as well as by the Prince of Wales in his role as patron of the British Legion. In 1924 there were talks of performances of the World Requiem being arranged in Seattle, Vancouver, Sydney and Bombay, and broadcasts by the BBC. It was also known that Haig had requested that this would be a piece of music which could be performed simultaneously in the United Kingdom every Armistice Day. Ahead of the second “Festival Commemoration,” performance of the World Requiem at the Royal Albert Hall on Armistice Night 1924, the British Legion’s Appeal Department ran a campaign to encourage local musical groups to perform the World Requiem on Armistice Night throughout the United Kingdom. The Legion sent out a letter written by Haig which asked local choirs to establish and maintain annual Festival Commemoration Performances of all or portions of the World Requiem, in aid of the Haig Appeal for ex-servicemen of all ranks.

The relationship between the British Legion and Foulds appears to have broken down in the mid-1920s. The exact reasons for this remain unclear, but archival evidence appears to suggest that the financial cost to the Legion of putting on the Armistice concert had become a key concern. Fund-raising concerts were an important source of income for the British Legion during the first years of the organisation’s existence. In addition to the annual Festival of Remembrance concerts, the Legion also held regional and national band contests to bring in much needed revenue to the charity, with the results of the competitions and the amounts raised reported in the British Legion journal. As a result of the disagreement with Foulds, the World Requiem was not performed in the Royal Albert Hall on Armistice Night 1925, but a performance did go ahead at the Queen’s Hall.

Contested Remembrance↑

The British Legion obtained its Royal Charter in 1925. By this time the organisation believed the change from “Mafficking”[8] and uncontrolled rejoicing on 11 November had taken seven years to stabilise, but that the change had occurred and was seen as a “great opportunity”[9] for the organisation. The British Legion journal asserted that, “Never before has the whole Nation – nay the whole Empire – shown itself so completely in unison in its desire to do homage to the dead whilst assisting the living.”[10] In reality, people were less united on the question of commemoration, a fact revealed by a dispute between the Daily Mail and Daily Express set against a backdrop of class antagonism, unemployment, strikes and economic instability. While the Daily Mail supported the World Requiem and the solemn nature of all remembrance rituals, the Daily Express believed that the daytime commemorative ceremonies were sufficient to honour the dead and, in an echo of the motto of the British Legion, the evening should allow the nation to focus on the living. The Daily Express, owned by the Canadian magnate and former Minister of Information Max Aitken, Lord Beaverbrook (1879-1964), decided that the tone of previous celebrations had been too elitist and sombre.

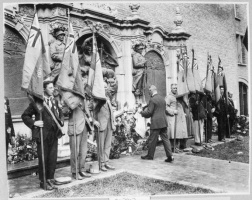

From 1927 the Daily Express secured the Royal Albert Hall for the annual Armistice Night concert. The paper’s two year tenure of the event marks a clear change in tone of the character of British national remembrance on Armistice Night. By 1927 the Home Office, the War Office and the Admiralty felt that the ex-service community should be more fully represented at the Cenotaph ceremony which had been held every November since 1920, and British Legion Headquarters were asked to organise an ex-service parade past the monument. In the same year, the Daily Express approached the Legion suggesting there should be a corresponding evening event – a reunion rally of ex-servicemen and women in the Albert Hall. The Legion’s National Executive Council agreed. The event would include the singing of congregational hymns and the demand for tickets was huge. Owing to this high demand, places had to be limited to those who had served in war areas and British Legion Headquarters allotted seats for the event by Divisions. Ultimately, as many as 10,000 veterans attended. Once the singing was finished the assembly filed out of the Albert Hall for a torch lit “All London” march to the Cenotaph. Led by the Prince of Wales, once the procession reached Knightsbridge the “immense column” was joined by a large number of veterans who had been unable to secure tickets for the Albert Hall and had instead gathered in Hyde Park. On the way to the Cenotaph the British Legion reported that the column had been joined by “enthusiastic and appreciative Londoners” which swelled the column’s numbers and was proof that “the people of London had risen in their masses to march with the British Legion.”[11] However, Armistice Night 1927 was the only time the running of the Festival was in the sole hands of the Daily Express. Serious concerns about the march and the Prince’s safety meant that the following year the event was organised by the British Legion’s General Secretary.

The British Legion from the Inter-war Period Onwards↑

The post-war period was a difficult time for the British Legion. High unemployment from 1921, particularly among ex-servicemen, was the Legion’s greatest post-war challenge. It was estimated that out of 2 million unemployed men, 600,000 were veterans. The Legion sought to protect vulnerable ex-servicemen and their families while at the same time trying to change the circumstances which caused the misery. British Legion branches established local Relief Committees in an attempt to support ex-servicemen and their dependents who would otherwise be reliant on the Poor Law. A loan scheme was founded to help veterans start their own businesses. Campaigning continued for disabled and shell-shocked soldiers to obtain pensions, a TB treatment centre was established and pilgrimages to the former battlefields were funded and organised.[12]

However, some historians have downplayed the significance and popularity of the British Legion in the immediate post-war period. Membership never exceeded 500,000, approximately 10 percent of the total number of British men who fought for Britain in the 1914-1918 period and a very small number in comparison to France where 3 million ex-servicemen joined a similar organisation.[13] Reasons given for this lack of popularity include the Legion’s determination to remain detached from politics, the perceived dominance of officers and the lack of success in its campaigning with the exception of the Poppy Appeal.[14]

The events of the Miners’ Strike and the General Strike in 1926 forced the Legion into committing to political action regarding pensions and employment policy which fundamentally changed its character. On 8 May 1926 the General Secretary Colonel Heath called upon members to help man national services including public transport. A statement printed in The Times “calls upon all ex-servicemen who saved the country in the war, to come forward once more and offer their services in any way that may be needed by the authorities.”[15] This led to a serious deterioration in the relationship between the Legion and the Officers’ Association. In January 1930 the Sunday Express attacked the Legion over its use of funds and argued that trading activities were being mismanaged. The charges followed the Legion’s National Executive Council’s summary dismissal of the Metropolitan Area Organizing Secretary after loss of funds in the area. The Sunday Express asserted that there might be flaws in the financial affairs of the Legion, particularly its investments in businesses, a number of which had failed. The paper also called for the disclosure of salaries of British Legion staff and subsistence allowances for disabled servicemen. John Jellicoe, Earl Jellicoe (1859-1935), who had served as Admiral of the Fleet during the war, was forced to respond and defend the financial security of the organisation in the strongest of terms.[16]

Conclusion↑

After the tumultuous interwar years the British Legion survived a second war. Today it continues to lead Britain’s national calendar of remembrance with the Poppy Appeal, the Remembrance Day march past the Cenotaph and the Festival of Remembrance concerts at the Royal Albert Hall. The British Legion continues to work for the benefit of all ex-servicemen and their dependents and offers support and guidance for those leaving the services as well as the injured and bereaved from more recent conflicts.

Emma Hanna, University of Kent

Section Editor: Edward Madigan

Notes

- ↑ Ward, Stephen (ed.): The War Generation: Veterans of the First World War, London 1975, pp. 10-12.

- ↑ Bottomley quoted in Ward, The War Generation 1975, p. 18.

- ↑ Ward, The War Generation 1975, pp. 18-20.

- ↑ Claxton, Major General P.F.: The Regular Forces Employment Association (National Association for the Employment of Regular Soldiers, Sailors and Airmen) 1885-1985, p. 21.

- ↑ DeGroot, Gerard: Blighty: British Society in the Era of the Great War, London 1996, pp. 344-345.

- ↑ DeGroot, Gerard: Blighty: British Society in the Era of the Great War, London 1996, pp. 344-345.

- ↑ DeGroot, Gerard: Blighty: British Society in the Era of the Great War, London 1996, pp. 344-345.

- ↑ British Legion Journal 5/6, December 1925, p.1. The term ‘Mafficking’ dates from Britain’s involvement in the Second Boer War (1899-1902) and refers to boisterous and uncontrolled rejoicing by the public after the news that the siege of the British-held town of Mafficking had been relieved in 1900.

- ↑ British Legion Journal 5/6, December 1925, p.1.

- ↑ British Legion Journal 5/6, December 1925, p.1.

- ↑ British Legion Journal 7/6, December 1927, p.1.

- ↑ Harding, Brian: Keeping Faith: The History of the Royal British Legion, Yorkshire 2001, pp. 69-87.

- ↑ DeGroot, Blighty 1996, p.345.

- ↑ DeGroot, Gerard: Back in Blighty: The British at Home in World War I, London 2014, pp. 344-345.

- ↑ Wootton, Graham: The Official History of the British Legion, London 1956, p.90.

- ↑ Wootton, Graham: The Official History of the British Legion, London 1956, pp. 328-329.

Selected Bibliography

- Barr, Niall: The lion and the poppy. British veterans, politics, and society, 1921-1939, Westport 2005: Praeger Publishers.

- Claxton, P. F. / Regular Forces Employment Association: The Regular Forces Employment Association (National Association for Employment of Regular Sailors, Soldiers and Airmen), 1885-1985, London 1985: Regular Forces Employment Association.

- De Groot, Gerard J.: Back in Blighty. The British at home in World War One, London 2014: Vintage Books.

- De Groot, Gerard J.: Blighty. British society in the era of the Great War, London; New York 1996: Longman.

- Gregory, Adrian: The silence of memory. Armistice Day, 1919-1946, Oxford; Providence 1994: Berg.

- Harding, Brian: Keeping faith. The history of the Royal British Legion, Barnsley 2001: Leo Cooper.

- Leed, Eric J.: No man's land. Combat & identity in World War I, Cambridge; New York 1979: Cambridge University Press.

- MacDonald, Malcolm: John Foulds. His life in music, Rickmansworth 1975: Triad Press.

- Mosse, George L.: Fallen soldiers. Reshaping the memory of the world wars, New York 1990: Oxford University Press.

- Ward, Stephen R. (ed.): The war generation. Veterans of the First World War, Port Washington 1975: Kennikat Press.

- Wootton, Graham: The official history of the British Legion, London 1956: Macdonald & Evans.