A Poorly Timed Epic↑

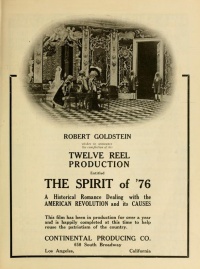

Robert Goldstein (1883-?), a son of German Jewish immigrants, opened a branch of his family’s costume firm in Los Angeles in 1912 to supply wardrobes to the burgeoning film industry. Following the success of David Wark Griffith’s (1875-1948) Birth of a Nation (1915), for which he was both the costumer and an investor, Goldstein sought to produce a similarly big-budget melodrama about the American Revolution.

The Spirit of ’76 was completed shortly before the United States entered World War I in April 1917. It premiered in Chicago on 28 May, but only after the head of the city’s police censorship board – concerned that the film would arouse antagonism toward Britain, now a wartime ally – insisted that Goldstein cut scenes depicting British atrocities.

Before the film opened in Los Angeles in November, Goldstein was required to host a private screening for officials concerned about its anti-British content. The picture was approved, but it was seized after only two public showings when it was discovered that Goldstein had, after the special screening, reinserted the atrocity scenes. Goldstein later admitted doing so to make the movie more exciting.

Arrest and Trial↑

Goldstein was arrested for violating the Espionage Act (enacted on 15 June 1917). On 4 December 1917, a federal grand jury indicted him on three counts, charging that he had willfully attempted to cause insubordination among United States military forces by inciting hatred of Britain and its soldiers, and that he had done so to aid the German government.

At Goldstein’s trial, which began on 3 April 1918, the avowedly anti-German presiding judge gave the prosecution wide latitude to make its case that the film was intended to aid the German cause and reflected Goldstein’s deep-seated anti-British and pro-German sentiments. With anti-German feeling at its height, and with movies not constitutionally protected as free speech at the time, the verdict was a foregone conclusion. Convicted on two counts, Goldstein was sentenced to ten years in prison (later commuted to three years) and fined $5,000.

Aftermath and Legacy↑

The severe sentence and resulting bankruptcy of Goldstein’s company sent a strong signal to the wartime movie industry that it should avoid making films that could run afoul of the government’s strictures against unfavorable depictions of the country’s allies.

In his landmark study establishing modern First Amendment theory, Freedom of Speech (1920), Harvard law professor Zechariah Chafee, Jr. (1885-1957) cited Goldstein’s prosecution as an example of how the Espionage Act operated to unjustly punish expressions of opinion. Modern commentators agree that Goldstein’s reinsertion of the atrocity scenes was foolish but not traitorous, and that he was a victim of the government’s overly zealous curtailment of civil liberties.

No print of the film has survived.

Mark Levitch, National Gallery of Art

Reviewed by external referees on behalf of the General Editors

Selected Bibliography

- Chafee, Jr., Zechariah: Freedom of speech, New York 1920: Harcourt, Brace and Howe.

- Fishman, Donald: George Creel. Freedom of speech, the film industry, and censorship during World War I, in: Free Speech Yearbook 39/1, 2001, pp. 34-56.

- Selig, Michael: United States v. motion picture film 'the spirit of ’76', in: Journal of Popular Film and Television 10/4, 1983, pp. 168-174, doi:10.1080/01956051.1983.10661939.

- Slide, Anthony: Robert Goldstein and 'the spirit of '76', Metuchen 1993: Scarecrow Press.

- Stokes, Melvyn: D. W. Griffith's 'The birth of a nation'. A history of 'the most controversial motion picture of all time', New York 2007: Oxford University Press.