Introduction↑

Jaroslav Hašek (1883-1923) is probably the most internationally esteemed Czech writer. This is almost solely due to his post-war epic novel Osudy dobrého vojaka Švejka za světové války (The Good Soldier Švejk), published as a series of popular readings between 1921 and 1923 (when Hašek died, leaving the story unfinished). The quality of the work was widely discovered in the second half of the 1920s when German translation and scenic adaptation paved the way for the book’s international career. Since then, it has primarily been interpreted as a powerful manifesto of pacifism, hence frequent comparisons to Erich Maria Remarque (1898-1970) or Henri Barbusse (1873-1935). However, almost simultaneously, another direction in the novel’s interpretation was taken by communist literary critics keen at reading the book as a radical left manifesto. This tradition, based on autobiographic reading of the novel, continued in the literary history of post-1945 Czechoslovakia and the rest of the Soviet bloc until 1989. In the long run The Good Soldier Švejk unveils special qualities as a historical source on the everyday Austro-Hungarian war effort, comparable to the The Last Days of Mankind by Karl Kraus (1874-1936). Despite the apocalyptic background of Hašek’s story, it remains a humorous novel.

The Good Soldier Švejk and its Author↑

The book’s somewhat chaotic plot consists of stories, scenes and gags united by the main character, Švejk, a Czech soldier of the 91st Infantry Regiment from České Budějovice (Budweis). The story starts in the aftermath of the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria-Este (1863-1914) and ends on the Galician front. With his down-to-earth attitude Švejk challenges the machinery of the Austro-Hungarian military bureaucracy while experiencing subsequent stages of “career”, from mobilization through military hospital, garrison arrest, service as an adjutant, transport to the front and even capture (ironically, not by the enemy).

Many a motif of this story corresponds to Jaroslav Hašek’s own wartime experience. Journalist and vagabond, he served in the 91st Regiment and, in 1915, got captured on the Galician front (apparently on his own will). In Russia he entered the Czechoslovak Legion, fought with it against his former comrades, became a propagandist and recruiting officer, but, in 1918, deserted to the Red Army. There, he became a political commissioner to the Fifth Red Army, in whose ranks he reached Siberia, only to return to Prague in December 1920.

Some details from Hašek’s biography and his œuvre represent a challenge in the face of scarce documentary sources but, even more so, because of his tendency to turn personal experience into storytelling. Notably, his Russian adventures never wholly materialized from the cloud of gossip and myths.

The Czechoslovak Context↑

Hašek’s antiheroic narrative did not conform to the Czechoslovak self-image petrified in the “legionary literature” (i.e. depicting the struggle of Czech and Slovak military units on the side of the Entente) by authors like Rudolf Medek (1890-1940), František Langer (1888-1965) or Josef Kopta (1894-1962). Nor did Hašek himself adhere to the rules of the writers’ guild. Deemed (rightly) a traitor to the national cause and a Bolshevik, he died as a marginal figure. In addition, the novel’s main figure seemed to confirm wartime, and mostly unfair, accusations against Czech nationals as especially prone to desertion. This unfavorable association petrified into the notion švejkovština, denoting subversion and unethical pragmatism allegedly characteristic of the Czechs.

International Career↑

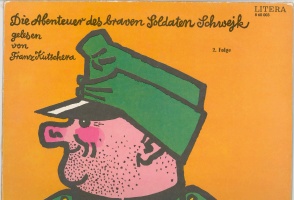

The international career of The Good Soldier Švejk was initiated by Max Brod (1884-1968) who first translated parts of the novel into German. Then, in 1926, the whole of it was published in Germany with the translation by Grete Reiner-Straschnow (1892-1944), which served as a basis for further translations (with some exceptions, i.e. the Polish 1931 translation by Paweł Hulka-Laskowski (1881-1946) was based on the Czech original). A boost to the novel’s popularity was given by Erwin Piscator’s (1893-1966) dramatization staged in Berlin in 1928. Since then, Hašek’s late success manifested itself in numerous new translations into almost all languages and many film versions, including the 1957 Czechoslovak production directed by Karel Steklý (1903-1987).

Wartime and Post-war Interpretations↑

Contrary to the critical reactions of the Czechoslovak public, the local communist movement consequently praised the artistic value of Hašek’s novel. Furthermore, in the eyes of the communist authors Zdena Ančík (1900-1972), Julius Fučík (1903-1943), Milan Jankovič and, most of all, Radko Pytlík, the novel unveiled political meanings as a "proletarian" narrative. Since 1955 Hašek’s œuvre has been meticulously collected and published in a series titled Spisy Jaroslava Haška; the lists of publications devoted to him are continuously monitored and published in the journal Česká literatura. Bertold Brecht (1898-1956) authored a dramatic piece on anti-Fascist Švejk’s fortunes during the Second World War (staged in 1957). In this vein, ironically, in the 1950s to 1980s, a communist interpretation concentrated not upon the novel itself but, rather, on its unwritten, potential following parts. Pytlík and other "Haškologists" in Czechoslovakia, the Soviet Union and elsewhere argued that, had he been able to, Hašek would surely have led his hero into the ranks of the Red Army. Since 1989 this tradition has been largely missing, giving way to a variety of interpretations and a vital tourist industry.

Maciej Górny, Deutsches Historisches Institut Warschau and Instytut Historii PAN im. Tadeusza Manteuffla

Section Editor: Tamara Scheer

Selected Bibliography

- Hanshew, Kenneth: Švejkiaden. Švejks Geschicke in der tschechischen, polnischen und deutschen Literatur, Frankfurt a. M. 2009: Lang.

- Měšťan, Antonín: Haškologie - eine neue bohemistische Disziplin?, in: Zeitschrift für Slavische Philologie 45/2, 1986, pp. 446-455.

- Parrott, Cecil: Jaroslav Hašek. A study of Švejk and the short stories, Cambridge; New York 1982: Cambridge University Press.

- Pytlík, Radko: Kniha o Švejkovi (A book about Švejk), Prague 1983: Československý spisovatel.