Literary-historical Aspects↑

Inspired by the sight of undernourished Armenian refugee children in Damascus, Franz Werfel (1890-1945) narrates, in his famous novel, the fate of several thousand Armenian villagers who fled from their imminent deportation to a nearby mountain and hid there until they could escape on naval vessels of the Entente over the sea. Although the novel was banned in Nazi-ruled Germany and in Turkey shortly after its publication in 1933, it played a significant role in making the deportations and massacres of at least several hundred thousand Ottoman Armenians generally known. Werfel's novel still takes a special position among literary treatments of genocide in general, as reflected in the reception of works by Edgar Hilsenrath, Jochen Mangelsen and Peter Balakian.[1] How controversially Werfel’s work is still received today becomes clear from the Turkish opposition to efforts at making a film adaptation of the novel.[2]

Historical Background↑

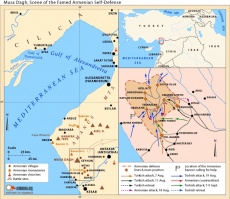

Werfel’s novel relies on documents about the resistance struggle surrounding a coastal mountain known as the Mountain of Moses or Musa Dagh (also spelled as Moussa Dagh, in today’s Turkish: Musa Dağı, Armenian: Mus(s)a Ler, Arabic: Jebel Musa or Gebel-Moussa, French: Mont Moïse), located in Cilicia, a region in south western Turkey adjacent to Syria.[3] The historical incident is unique as it represents one of only two successful attempts by Armenian communities to resist deportation and genocide (the other example is Van in eastern Turkey).[4] One of the earliest reports was penned by the Protestant pastor Digran Andreasian (1888-1961).[5] Andreasian had witnessed the deportations in Zeitun from which he was exempted by fortunate circumstance. He returned to his home village located at the foot of the Musa Dagh massif. He reported that on 30 July 1915 the inhabitants of altogether six adjacent Armenian villages had received an ultimatum from Ottoman officials to prepare for their deportation within a week. The majority of the villagers, altogether some five thousand individuals, decided to take their weapons, livestock and as much supplies as possible and escape to the Musa Dagh. There they established fortifications and organised their defence.[6]

The Ottoman troops failed repeatedly to overcome the resistance fighters. It is unclear to what extent German officers, namely Eberhard Count Wolffskeel von Reichenberg (1875-1954), were involved in these actions.[7] The count not only fought, like hundreds of other officers, in the German military mission, but even held the rank of chief of staff in the Ottoman army.[8] At Musa Dagh, in his function as chief of staff of the Eighth Ottoman Army Corps, he might only have taken the role of an observer, but he might have been involved in conducing the siege as well.[9]

After several weeks of siege, the escapees were running low on supplies and intensified their attempts to attract the attention of the Entente powers by raising two huge banners on the mountainous coastline as a call for help.[10] This finally caught the attention of a French cruiser, the Guichen, whose commander Jean Joseph Brisson (1868-1957) informed his superiors about the refugees’ request for humanitarian relief. After a telegraphic communication between French and British authorities, the rear admiral on the French flagship Sainte Jeanne d’Arc received permission to guide the Armenians to a refugee camp in Port Said in Eqypt.[11] On 12 and 13 September, the refugees boarded the French cruisers Guichen, Desaix, Amiral Charner, Destrées and Foudre while the French bombarded the Ottoman army positions on the shore.[12] According to Andreasian, a British ship was involved as well. On 14 September 1915, over 4,000 refugees arrived in British-ruled Port Said.[13]

In 1919, the refugees returned to their homes.[14] Prior to this, 600 of them, all young men, had already joined a French volunteer legion. The attempts to establish Cilicia as an autonomous region failed, but the villages at the Musa Dagh remained part of the French-ruled Sanjak of Alexandretta.[15] In the course of the Sanjak’s annexation to Turkey in 1939 (termed Hatay province thereafter), all returnees except the villagers of Wagef (Turkish: Vakıf) opted for flight again. Many settled in Anjar in Lebanon, others moved to the present-day Republic of Armenia.[16]

Hatice Bayraktar, Simon Fraser University

Section Editor: Alexandre Toumarkine

Notes

- ↑ See Eke, Norbert Otto: (1997). Zwei Versuche über das Unfaßbare des Völkermordes: Franz Werfels Die vierzig Tage des Musa Dagh (1933) und Edgar Hilsenraths Das Märchen vom letzten Gedanken (1989), in: Deutsche Vierteljahresschrift für Literaturwissenschaft und Geistesgeschichte, 71 / 4) (1997), pp. 701-723. Ohandjanian, Artem: Armenien - Der verschwiegene Völkermord, Wien, Köln, Graz 1989, pp. 222-232; and Karsten, Stefan: Der Völkermord an den Armeniern in Romanen von Werfel, Hilsenrath, Mangelsen und Balakian. Norderstedt 2007.

- ↑ Welky, David: Global Hollywood versus National Pride: The Battle to Film The Forty Days of Musa Dagh, in: Film Quarterly, 59 / 3 (2006), pp. 35-43.

- ↑ See Mahler-Werfel, Alma: Mein Leben. Frankfurt am Main 1960, p. 210; and Ohandjanian, Armenien - Der verschwiegene Völkermord, p. 224.

- ↑ Bloxham, Donald: The Great Game of Genocide. New York 2005.

- ↑ Toynbee, Arnold. (ed.): The Treatment of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire 1915-1916: Documents presented to Viscount Grey of Falladon, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs. London 1916, online: https://archive.org/details/treatmentofarmen001963mbp (retrieved: 15 December 2016).

- ↑ Ibid.

- ↑ Kaiser, Hilmar (ed.): Eberhard Count Wolffskeel von Reichenberg: Zeitoun, Mousa Dagh, Ourfa: Letters on the Armenian Genocide. Princeton, London 2004.

- ↑ See Bihl, Wolfdieter: Die Kaukasus-Politik der Mittelmächte. Wien, Köln, Graz 1975, p. 53. As well his 1985 book Die Armenische Frage im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Ohandjanian, Artem (ed.): 1915-1985: Gedanken über einen Völkermord. Wien 1985, pp. 177-178.

- ↑ On his role of observer see Dadrian, Vahakn Norayr: German Responsibility in the Armenian Genocide.Watertown, Massachusetts 1996, p. 136. And on the siege, see Hofmann, Tessa: Annäherung an Armenien: Geschichte und Gegenwart. München 2006, p. 102.

- ↑ Toynbee, Document 130, online: https://archive.org/stream/treatmentofarmen001963mbp#page/n553/mode/2up (retrieved: 15 December 2016).

- ↑ Kévorkian, Georges: La flotte française au secours des Arméniens en 1909 et 1915: les escadres des amiraux Pivet et Darrieus au Levant. Rennes 2008, pp. 71-89.

- ↑ See Kévorkian, p. 76 and Toynbee, Document 131.

- ↑ Toynbee, Documents 130 and 131 online: https://archive.org/stream/treatmentofarmen001963mbp#page/n553/mode/2up (retrieved: 15 December 2016).

- ↑ Hofmann, Tessa / Koutcharian, Gerayer: Diarbekir und Hatay: Flüchtlingsberichte, in: Pogrom: Zeitschrift für bedrohte Völker 12 /85 (1981), pp. 16-22.

- ↑ See Du Véou, Paul: La Passion de la Cilicie 1919-1922. Paris 1937. See also Kerr, Stanley E.: The Lions of Marash: Personal Experiences with American Near East Relief, 1919-1922. Albany, New York 1973.

- ↑ Hofmann and Koutcharian: Flüchtlingsberichte. For more details on the Armenians of the Musa Dagh and their resistance see Goušagdžean, Martiros / Matouran, P. (ed.): Housametean Mousa Leran [Collection of Memories of Mussa Ler]. Beirut 1970; Svazlyan, Veržine: Mowsa Leṙ. Yerevan 1984; Gyozalyan, Grigor Erevan M.: Mowsa Leṙan azgagrowt'yownẹ [Ethnograpy of Musa Dagh]. Yerevan 2001; Bloxham: The Great Game of Genocide; Ohandjanian, Artem: Armenien 1915, österreichisch-ungarische Botschaftsberichte beweisen das Genozid. Wien 2007; Gust, Wolfgang (ed.): Der Völkermord an den Armeniern 1915/16. Dokumente aus dem Politischen Archiv des deutschen Auswärtigen Amts. Springe 2005. See also Internet edition on www.armenocide.de.

Selected Bibliography

- Bloxham, Donald: The great game of genocide. Imperialism, nationalism, and the destruction of the Ottoman Armenians, Oxford 2005: Oxford University Press.

- Dadrian, Vahakn N.: German responsibility in the Armenian genocide. A review of the historical evidence of German complicity, Watertown 1996: Blue Crane Books.

- Eke, Norbert Otto: Zwei Versuche über das Unfaßbare des Völkermordes. Franz Werfels Die vierzig Tage des Musa Dagh (1933) und Edgar Hilsenraths Das Märchen vom letzten Gedanken (1989), in: Deutsche Vierteljahresschrift für Literaturwissenschaft und Geistesgeschichte 71/4, 1997, pp. 701-723.

- Hofmann, Tessa; Koutcharian, Gerayer: Diarbekir und Hatay: Flüchtlingsberichte, in: Pogrom. Zeitschrift für bedrohte Völker 12/85, 1981, pp. 16-22.

- Karsten, Stefan: Der Völkermord an den Armeniern in Romanen von Werfel, Hilsenrath, Mangelsen und Balakian, thesis, Lüneburg 2007: Universität Lüneburg.