Film Background↑

Battle of the Somme was a feature-length British documentary film, shot on the western front in June and July 1916 and released while the Somme battle was still in progress. In 1915 the British government effectively sold the film rights to the war on the western front to a small group of commercial news film companies. In peacetime a single one of them would have used a dozen cameramen to film a big sporting event like the Derby, but the War Office would only authorize two cameramen for the entire British front. General Headquarters (GHQ) in France was also cautious about what could be shown and the short official films released before July 1916 made little impact.

Recording the Somme↑

On the eve of the Somme battle the commercial cameramen at GHQ were Geoffrey Malins (1886-1940), an experienced newsreel photographer, and John Benjamin “Mac” McDowell (1878-1954), a senior film producer and director. Malins and McDowell were permitted to film the build-up to the Somme attack and on 1 July 1916 they were both in the front line for the start of the “Great Push.” Malins filmed the detonation of a huge mine under the German lines, which signaled the infantry attack and then filmed British troops in the distance advancing across no man’s land. McDowell also filmed the attack and was officially reported to have taken “considerable risks...notably from machine-gun bullets...when trying to cross ‘no man’s land’ behind the advancing infantry.”[1]

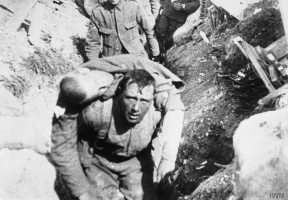

The two cameramen filmed widely over the next few days and on 10 July 1916 returned to London with two-and-a-quarter hours of negatives. Their footage was so striking that the influential producer Charles Urban (1867-1942) decided that it must be edited into a single feature documentary. Its climax would be the infantry attack from the trenches, which both Malins and McDowell had seen and filmed. But Urban faced a problem, for Malins had only filmed from a distance and McDowell’s attack footage was apparently unusable. It seems that Malins was thus sent back to France to recreate the attack at a British trench-mortar training school behind the lines, and film the vital missing close-ups.

Reception↑

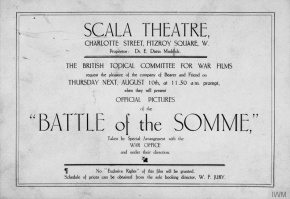

Urban’s completed film ran for over an hour and opened at thirty-four London cinemas on 21 August 1916, while the fighting was still in progress. It had a huge impact, pushing the boundaries of what was acceptable in British cinema. The shots of dead and wounded soldiers, spread throughout the film, lasted more than ten minutes and Malins’ brief staged close-ups were especially shocking, for they appeared to show British soldiers actually being killed. One London cinema manager became notorious for displaying the sign: “WE ARE NOT SHOWING THE BATTLE OF THE SOMME. THIS IS A PLACE OF AMUSEMENT, NOT A CHAMBER OF HORRORS.”[2]

Despite this controversy it was estimated that 1 million Londoners paid to see Battle of the Somme during its opening week. The Evening Star declared “that the Somme pictures have stirred London more passionately than anything has stirred it since the war. Everybody is talking about them. Everybody is discussing them. Everybody is debating the question whether they are too painful for public exhibition.”[3] During the first six weeks of general release Battle of the Somme was shown at 2,000 British cinemas and probably reached an audience in excess of 10 million. It went on to attract large audiences in allied and neutral countries.

Battle of the Somme is a remarkably accurate film, whose images appear in virtually every modern documentary about the war. Its staged sequences are still controversial, but these interventions were virtually unavoidable with only two cameramen and they amount to little more than a minute of screen time or less than the staged sequences in any modern television documentary of comparable length. The film is a fundamentally honest record of the battle’s opening days and in 2006 it was rightly entered into UNESCO’s “Memory of the World Register” as an historical document of world significance.

Nicholas Hiley, University of Kent

Section Editor: Catriona Pennell

Notes

- ↑ British Film Institute Library, London, Related Material 1504, “World War I: 4,” pp. 20-21.

- ↑ British Film Institute Library, London, Related Material 1504, “World War I: 2,” pp. 3-4 (copy of article from London Evening Standard, August 1916).

- ↑ Douglas, James: “The Somme Pictures – Are They Too Painful for Public Exhibition?”, The Star [London], 25 August 1916, p. 2.

Selected Bibliography

- Fraser, Alastair H. / Robertshaw, Andrew / Roberts, Steve: Ghosts on the Somme. Filming the battle, June-July 1916, Barnsley 2009: Pen & Sword Military.

- Hiley, Nicholas: 'Introduction' to the Imperial War Museum and Battery Press reprint of Geoffrey Malins’ 'How I filmed the war': How I filmed the war. A record of the extraordinary experiences of the man who filmed the great Somme battles, etc., London; Nashville 1993: Imperial War Museums; The Battery Press, pp. 15-50.

- Malins, Geoffrey H. / Warren, Low / Hiley, Nicholas: How I filmed the war. A record of the extraordinary experiences of the man who filmed the great Somme battles, etc., London; Nashville 1993: Imperial War Museums; The Battery Press.

- Reeves, Nicholas: Cinema, spectatorship and propaganda. ‘Battle of the Somme’ (1916) and its contemporary audience, in: Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 17/1, 1997, pp. 5-28.

- Williams, Hugh Noel: Sir Douglas Haig's great push. The battle of the Somme; a popular, pictorial and authoritative work on one of the great battles in history, illustrated by about 700 wonderful official photographs & cinematograph films and other authentic pictures, London 1916-1917: Hutchinson.