Introduction↑

This article will survey the effects of the First World War on Southern Africa, drawing from monographs as well as survey histories of the war and the region. The region’s history during wartime has been explored in several important books. A short introduction may be found in the relevant chapter of Ian van der Waag’s A Military History of Modern South Africa (2015). An excellent overview can be found in Bill Nasson’s Springboks on the Somme: South Africa in the Great War, 1914-1918 (2007) and also in his WWI and the People of South Africa (2014). The experience of South Africa’s African population is traced by Albert Grundlingh in Fighting Their Own War: South African Blacks and the First World War (1987). The experience of laborers in the British colony of Nyasaland, which is today called Malawi, is related by Melvin E. Page in The Chiwaya War: Malawians and the First World War (2000). Military and social aspects of the war in Southern Africa have been covered well in several books about the wider war in Africa. These include Hew Strachan’s The First World War in Africa (2004) and Africa and the First World War (1987), edited by Melvin E. Page.

Prelude to War in Southern Africa↑

Many historians believe that the First World War was the modern world’s watershed in which stable political, economic and social orders broke down under the strains of total war. Modern weaponry in the hands of land-hungry nationalists produced unprecedented dislocations, including forced mass migrations and famines. On the battlefields, industrialized slaughter caused many people to abandon faith in progress. Yet, in Southern Africa, the First World War did not produce such great transformations. Many of these transformations had actually already occurred in the 19th century, with significant instances of migration and famine, as well as the rise of new states that were often in conflict with each other. Territorial conquests by Europeans with industrial weaponry were marked by ever-higher levels of slaughter.

The 19th century was a time of significant transformation in Southern Africa. The early decades of the century witnessed the expansion of new indigenous states, such as the Zulu, Sotho, and Ndebele, as well as mixed-race polities like the Griqua. At the Cape, the transition from Dutch rule to British rule during the Napoleonic Wars, combined with the abolition of slavery in the 1830s, persuaded many Dutch farmers and herders, called “Boers,” to move into the interior, where they formed their own republics. British settlement in the Eastern Cape and Natal produced tension over access to land and labor, experienced most acutely in a long series of wars that pitted the British against the Xhosa and the Zulu. British settlement extended to Zimbabwe, where Ndebele and Shona independence was abrogated in the 1890s, resulting in their land being taken by the British South Africa Company and distributed to settlers. Polities in Zambia and Malawi lost their independence, too, while the French consolidated their hold on Madagascar. On Britain’s island colony of Mauritius in the southwest Indian Ocean, the abolition of slavery in the 1830s resulted in the importation of 452,000 indentured laborers from India by the time of the First World War. In the same time period, 111,000 indentured Indians migrated to the French island of Réunion, while 152,000 migrated to Natal. Population movements attributable to the problems of colonialism – and the consequent social and political tensions – formed the key theme of the region’s history in the century between the Napoleonic Wars and the First World War.

By the early 20th century, Southern Africa’s most important state was the Union of South Africa which had only been constituted in 1910. The union brought together the dominant British-ruled Cape Colony and the smaller British colony of Natal with the Afrikaner-led republics, the Orange Free State and the Transvaal, officially called the South African Republic. These colonies, over the course of the 18th and 19th centuries, had consolidated their own territories by defeating or containing Southern Africa’s indigenous states during a series of wars that were associated with settlement, famine and disease. Only a handful of polities remained separate from the union, having made special arrangements with the British to be ruled from London. These were the so-called “High-Commission Territories” of Basutoland (Lesotho), Bechuanaland (Botswana) and Swaziland. While independent, these states were closely linked to the union’s economy.

Political developments were driven to a large extent by changes in the Southern African economy. By the middle of the 19th century, a small capitalist economy had started to blossom in South Africa, based on the export of wine and wool, supplemented by the export of ivory and ostrich feathers. Capitalism developed further in the 1870s with the introduction of diamond mining in the vicinity of Kimberley, in the northern part of the Cape Colony, near the border with the Boer republic called the Orange Free State. Capitalism then grew to even greater significance with the advent of gold mining near Johannesburg in the South African Republic (or Transvaal). The growing city became a major global source of gold at a time when many currencies were linked to the metal. Mining gold near Johannesburg and diamonds in Kimberley drew laborers and engineers from Britain and Europe as well as the United States and Australia. African men also migrated to the mines from all over the region. At the diamond and gold mines, African mineworkers lived in barracks called closed compounds and were subject to various forms of coercion and surveillance.[1]

The gold mines were located in the independent Boer republic of the Transvaal which came to depend on British engineering and finance. Conflicts between Britons and Boers, fueled by aggressive actions by their governments, culminated in the South African War of 1899-1902, which pitted the Boer republics of the Transvaal and the Orange Free State against the British Empire. Initial Boer successes in battle were followed by a grinding, anti-guerrilla campaign by the British army in which the countryside was ringed by blockhouses, farms were torched and civilians were rounded up and placed in concentration camps where many of them died from disease and malnutrition. The Boer republics were forced to sign a peace treaty in 1902. The peace made possible negotiations for the unification of the two British colonies and the two Boer republics possible.

Even though the British won the war, the terms of the union were actually quite favorable to the Boers, in that rural votes were weighted more heavily than urban – and typically English-speaking – votes. The first union government was led by two former Boer generals, Louis Botha (1862-1919), a Transvaal landowner who served as the prime minister, and Jan Smuts (1870-1950), a Cambridge-educated attorney who served as the minister of the interior, defense, and mines. They recognized that under British oversight, white South Africans had many opportunities. These included the further development of mining, the regulation of the country’s African majority and the extension of Cecil Rhodes’ (1853-1902) vision, which involved the domination of the sub-continent by a unified, white-ruled South Africa that had close links to the British Empire.[2]

Further north, Rhodes’ British South Africa Company, chartered by the British government in 1889, was permitted to rule what is today Zambia and Zimbabwe, which then became known as Northern and Southern Rhodesia. In 1891, the company was given Malawi (then called Nyasaland). In the same year, the Portuguese government, which governed Mozambique, responded to the threat of British expansionism by allowing much of the colony to be governed by its own chartered companies. In the territories of both the British and Portuguese chartered companies, the slave and ivory trades were suppressed, ostensibly for humanitarian reasons, but with the intended consequence that African male labor would thus be freed for the South African gold and diamond mines.[3]

The new Union of South Africa supported mining by expropriating Africans. In the 1913 Natives Land Act, the government of Botha and Smuts outlawed black sharecropping on white lands while also restricting black buying and selling of land to 7 percent of the country. This was remarkable, as black people made up approximately 70 percent of the population and were mainly based in rural areas. The act had the effect of making rural blacks even more dependent and vulnerable. As more rural African men were forced to migrate to the mines to work, their cheaper wages often made them more attractive employees than white miners. The early years of the union saw increased white labor militancy and strikes which were met with police repression. Tensions between white and black laborers remained during the war years. The price of gold remained fixed at eighty-five shillings, even though the British Empire discontinued the gold standard. The British decided to pay for the war, in part, through inflation. Prices rose, stimulating South African agriculture and manufacturing. Yet the key industry, gold mining, could not increase prices, even though inflation caused a rise in costs. The mining industry could contain costs by replacing white workers with black workers but in the years before the war this strategy had inspired violent white strikes. During wartime, it was simply too politically risky to eliminate the “colour bar.”[4]

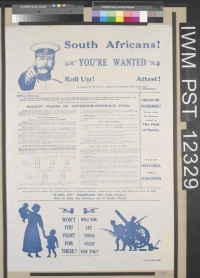

South Africa now had its own national government, yet in certain ways it remained dependent on Britain. The nominal head of government was a governor-general who was appointed by the British. The British also continued to control South Africa’s defense and foreign relations. These constitutional arrangements meant that in August 1914, Britain’s entry into the war automatically brought about the entry of South Africa. South Africa’s leaders saw the First World War as an opportunity to unify their nation, to expand their nation’s territory, and to demonstrate their worth to the British Empire. The leaders of non-European communities also voiced their support. The South African Native National Congress (SANNC), the forerunner of the African National Congress, famously voted to drop its campaign against the 1913 Natives Land Act until the end of the war, hoping that a pledge of loyalty would help their cause. However, the vote in the Congress was not unanimous. As Albert Grundlingh has discussed at length in his fine monograph, Fighting Their Own War, African responses to the war were highly variable, ranging from pledges of loyalty, to small strikes and rebellions to indifference. At the beginning of World War One, the British government withdrew its troops from South Africa, deploying them instead in European combat zones. South Africans now assumed responsibility for their own defense, subject to the oversight of the War Office in London. Some white South Africans feared that the departure of British troops might inspire a “native rising.” Many of the same voices hoped to continue to exclude Africans from armed service. African loyalty was still doubted by the Union of South Africa’s white leadership whose rural supporters, living in isolated communities, feared African retribution for a century of harsh treatment.

When Europeans initiated and prolonged the First World War on their own territory, they essentially did to themselves what people in Southern Africa had been experiencing for decades. In 1914, Europeans made themselves subject to the worst aspects of modernity by launching imperialist wars of aggression and conquest on their own continent. Many people from Southern Africa participated in the war, which ultimately accelerated the long-term effects of capitalism, imperialism and nationalism.

The Boer Rebellion of 1914↑

The outbreak of war presented Botha, Smuts and the union’s leadership with opportunities to strengthen their new state in the context of supporting the British Empire. Even so, continued ties to Britain remained a source of discomfort for a significant minority of Boer leaders. Longstanding antagonism between Boers and Britons, coupled with Britain’s harsh anti-guerrilla campaign during the war of 1899-1902, made it difficult for some to reconcile themselves to fighting a war on Britain’s side. Several of them remembered that in the run-up to the war of 1899-1902, the Boer republics received support from Germany. The test of Boer loyalty to the union government came when Britain declared war on Germany on 4 August 1914. Many South Africans of British descent supported the war, while Africans, Boers and Indians held various opinions. Botha and Smuts debated with their more reticent colleagues in the cabinet about Britain’s request for South African forces to invade German South-West Africa, today called Namibia. After a month the cabinet decided to grant Britain’s request but only if the South African parliament agreed and volunteer troops were used. During the cabinet deliberations, several well-known Boer military and political leaders began to plot a coup against British rule. When Britain declared war and South Africa’s government joined, those Boer dissenters declared independence and led 11,500 mounted soldiers on raids in rural areas in the hopes of sparking a widespread rebellion. Botha led loyal units against the rebels and succeeded in capturing or killing almost all of them.[5]

The South African Invasion of German South-West Africa↑

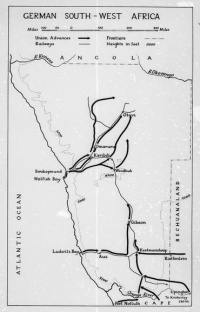

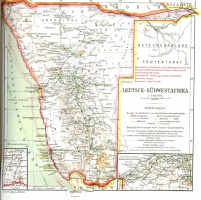

Botha’s main mission was to lead South African forces against the Germans in South-West Africa. The country occupies approximately twice the land area of Germany but German South-West Africa’s mainly arid environment ensured that the population was only about 200,000 whereas Germany’s was 65 million. 14,000 German settlers had immigrated to South-West Africa, attracted by farmland in the vicinity of Windhoek in the interior. Their settlement was made possible by a genocidal war that the German army fought between 1904 and 1908 against the Herero, local pastoralists who revolted against German rule. A German campaign reduced their number from 75,000 to 15,000 and took the lives of many thousands of their Nama and Baster neighbors as well. During the campaign the German army experienced 2,000 casualties. Some of the surviving German veterans went on to fight in the First World War and later to influence the Nazi party. The extent of the ideological and experiential connections has been contested.[6]

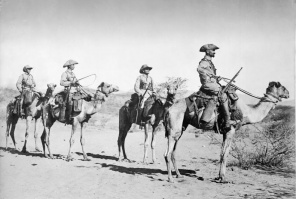

There were structural similarities between German South-West Africa and segregated South Africa. The German government in South-West Africa restricted citizenship to Europeans while also limiting racial intermarriage. Mining became an important industry in the region. As the war against the Herero was coming to a close, the Germans discovered diamonds near Lüderitz. The discovery produced a boom in mining while encouraging the development of towns and transportation. Labor was hard to find due to the recent genocide. The remaining Herero, Nama and Baster were typically required to work on settler farms so mineworkers had to be recruited from the Ovambo people in the far north near the border with Portuguese Angola. Despite these parallels, the Germans were particularly vulnerable to invasion from South Africa. Their 2,000 troops, 3,000 reservists and 500 police officers were not well prepared for war against fellow Europeans. They attempted to defend the colony as best as they could, though they certainly posed little threat to Britain’s colonies in Southern Africa which had numerically greater forces in the field and Britain’s navy controlling the coast.

British imperialist visions of conquest, coupled with the ambition of Botha, Smuts and other South Africans to unify their country by acquiring a sub-empire in the region, inspired an Allied attack on South-West Africa. The British navy landed a small South African force at Lüderitz. German forces, faced with the threat of naval gunnery, quite sensibly retired to the interior where they began to fight a delaying action. Meanwhile, at Sandfontein, near the border with South Africa, a force of 1,700 Germans captured three thousand South African troops who had been compromised by rebel Boers. To the north, another small German force with 500 troops skirmished with ten times as many Portuguese soldiers in Angola and succeeded in driving them away from the border region.[7] German successes were short-lived. Once the South African government succeeded in suppressing the Boer rebellion, it was able to turn its full attention to South-West Africa.

In early 1915, South Africa had 70,000 men in its armed forces with more than half of them ready to deploy to South-West Africa. Environmental conditions in South-West Africa limited the mobility of South African forces: water was particularly scarce, and, as the South Africans took control of the port of Swakopmund and began to advance on Windhoek, the capital in the interior, they found that the Germans had poisoned the wells. New wells proved slow to dig and yielded little water. Water had to be transported by ship and overland by motor vehicles. The South Africans hoped that their advance would follow the rail line from Swakopmund to Windhoek, but the Germans destroyed that as well. South African forces were forced to rebuild the railway as there was insufficient water and hay for mules to pull transport wagons and, in any case, the Germans had placed landmines on the roads.

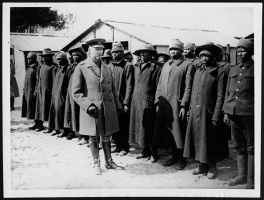

German forces executed strategic retreats, avoiding large-scale battles. What was left of the indigenous population hesitated to support their genocidal masters, hoping, along with the South Africans, to keep this conflict a “white man’s war.” That being said, in the final campaigns in South-West Africa, the South African force of 13,000 soldiers did employ 35,000 African laborers, including some from the adjacent High-Commission Territories. It was only in May 1915 that the South Africans, led by Botha, were able to capture Windhoek and its radio transmitting station. The Germans remained in control of the rest of the country but were forced to surrender in July. Combat casualties were very low compared to other theaters of the war and amounted to several hundred lost on both sides.[8]

The terms of the surrender were mutually advantageous. Botha’s government allowed the German reservists to return to their farms in the expectation that a South African administration of South-West Africa would depend on loyal settlers dominating the majority African people, just as in the union. This continuity meant that German settlers had little to regret about the change in administration though German national ambitions for an African empire had been thwarted. The lives of individual settlers remained much the same. Meanwhile, South African expansionists and nationalists received a boost. South-West Africa became integrated into the South African economy through investments in mines and other businesses as well as the development of railways, ports and roads. Nevertheless, the peace settlement of 1919 stipulated that South Africa could not incorporate South-West Africa. Instead, South Africa had to govern South-West Africa as a mandate of the League of Nations, a fig-leaf for the extension of settler colonialism.[9]

Southern African Labor in Wartime↑

The conquest of German South-West Africa was the main military campaign in Southern Africa during the war]]. In addition to the campaign, the Allies used Southern Africa as a ready source of labor and soldiers, thanks to the cooperation of settler leaders and colonial governments. These colonies had already been subject to exploitation before the war. Much of the land of Northern and Southern Rhodesia had been taken by the British South Africa Company to use for mining and agriculture. African protests against maladministration were seen in several violent rebellions, the most famous of which were the Ndebele and Shona Risings, or Chimurenga, of 1896-1897 in Southern Rhodesia. The leadership of the British South Africa Company, most prominently Cecil Rhodes, met the rebellion with ruthless suppression followed by some negotiation and the concession of reserved lands. In British Nyasaland, colonialism began with the establishment of Christian missions mid-century followed by the establishment of plantations for coffee, cotton and other crops. One African convert to Christianity, John Chilembwe (1871-1915), received an education at the Virginia Theological Seminary and returned, in 1900, to found his own mission. He noted the dissonance between Christian doctrines and colonial plantations and in 1914-1915 he led an unsuccessful revolt against labor recruitment practices.

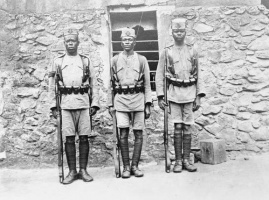

For African men, the experience of wartime recruitment was fairly similar to the recruitment of labor during the prewar years. Some volunteered for pay. Others found themselves coerced by colonial officials or chiefs who sought to meet government quotas. Some African men alternated working for both the Germans and the British, depending on the pay. The extent of recruitment for the British forces was vast. Workers were provided by the Union of South Africa as well as by all of Britain’s Southern African colonies: Basutoland, Bechuanaland, Southern Rhodesia, Northern Rhodesia, Nyasaland, Swaziland and even the island of Mauritius. The King’s African Rifles (KAR), a military unit unit that saw extensive service in East Africa, was composed mainly of British officers and African recruits from Uganda, Kenya, and Nyasaland, with some African men from Northern Rhodesia. African men from Northern Rhodesia also enlisted in the para-military Northern Rhodesia Police, which fought in East Africa throughout the war. The Rhodesia Native Regiment, which also fought in East Africa, was recruited in Southern Rhodesia, with most recruits having been migrant mine workers from Nyasaland and Northern Rhodesia.[10]

Generally speaking, white Southern African leaders and their British counterparts were uncomfortable with non-whites serving in combat roles, but there were significant exceptions. One such case involved the Cape Corps, a battalion made up of 1,000 soldiers from the Cape Colony’s so-called “coloured,” or mixed-race population, who fought in East Africa as well as Palestine. Another interesting exception involved soldiers in Zimbabwe. When the war began, white settlers formed the Rhodesia Regiment. Its first battalion supported South African units in the Boer Rebellion and in the conquest of South-West Africa, while the second battalion saw extensive service in East Africa. Disease diminished manpower, so, as Timothy Stapleton points out in his fine monograph, No Insignificant Part, the British High Commissioner in Cape Town and his subordinates in the government of the British South Africa Company decided, in 1916, to raise a regiment of African men. This was in spite of continuing white concerns about African restiveness. Initial recruitment focused on the Ndebele, as they were thought to be a more “martial race” than the Shona. A lack of manpower caused British and settler officials to rethink this policy, so that eventually the regiment included Shona, as well as migrant workers from Nyasaland, Northern Rhodesia, and Portuguese Mozambique. The unit was led by European officers and non-commissioned officers, who tended to reproduce the inequalities of colonial society within the regiment, from the time of its formation throughout its extensive service in the East Africa campaign.[11]

By contrast to the British, the French employed many African and Asian men as soldiers and bearers in both Africa and Europe alike. France’s principal colony in Southern Africa was Madagascar (the others being Réunion Island and the Comoro Islands). Madagascar, an island five-sixths the size of France with a wartime population of 3 million, contributed substantially to the French war effort. In the decade before the war, the French colonial government incorporated the leaders of the Merina kingdom into the colonial state’s bureaucracy as part of an effort to re-orient the economy toward production for export. As in British Southern Africa, the government encouraged efforts to develop mining and agriculture as well as settlement by Europeans. By 1913, the greatest profits were being made from rice-farming, grown mainly by settlers who benefited from government coercion of laborers. During the war, rice exports grew along with exports of graphite as well as lesser plantation crops such as vanilla and coffee. The war aligned the Madagascan economy even more closely with the needs of a colonial export-driven economy. To deliver more goods, Madagascan men were forced to serve thirty days out of the year on constructing roads and port facilities. During the First World War, Madagascar famously contributed troops to the French war effort. The first Madagascan men arrived in France in 1915 to work on roads and in factories. By 1916, Madagascan soldiers were serving in France in their own battalion, the Tirailleurs Malgaches (Madagascan Riflemen) with many others also serving in the heavy Artillery. Madagascan men were once thought not to be sufficiently warlike to serve to any great extent in the French army. Such racial stereotypes were susceptible to change thanks to the wartime need for recruits. All told, from 1916 to 1918, 41,000 Madagascan served, mainly in rear areas.[12]

French recruitment practices were also noted in Mauritius, Britain’s island colony in the Southwest Indian Ocean. Taken from France during the Napoleonic Wars, Mauritius was one of Britain’s most important sugar-producing colonies. In 1913, the island had 373,000 inhabitants living on only 2,040 square kilometers, making it easy to overlook compared to the rest of Southern Africa. Nonetheless, the island’s sugar-based economy was one of the most important in Southern Africa. In 1913, Mauritius imported the equivalent of 3.6 million pounds sterling annually, greater than the 3.4 million imported by Southern Rhodesia, Northern Rhodesia, and Nyasaland put together, while those three colonies together exported 1.1 million pounds compared to Mauritian exports valued at 3.3 million.[13] Mauritius had no indigenous inhabitants - the majority of Mauritians were descended from Indian indentured laborers who arrived after 1835 when the British freed the island’s African slaves. A small minority of Franco-Mauritians controlled the sugar estates while the more numerous Franco-African “Creoles” played a prominent role in the professions and the colonial bureaucracy. The British treated French-speaking Mauritians liberally, yet for some the war raised questions about the desirability of maintaining ties with London. Many Franco-Mauritians and Creoles noted that in France’s island colonies, such as the nearby island of Réunion, the descendants of the slaves who were emancipated in 1848 enjoyed full rights of citizenship, including the right, for men, to vote, while in Mauritius the property and income requirements of the 1886 constitution restricted voting to approximately two percent of the population – mainly wealthy planters and professionals as well as top civil servants. Mauritian Creoles noted that in Réunion, civic duties, in the form of military service, were balanced by civic privileges, such as male suffrage. During the war, a mainly Creole movement for the “retrocession” of Mauritius to France achieved some momentum but ultimately failed, thanks to British suppression combined with the dawning realization that if Mauritius became French again, the rival Indian majority was likely to be granted civic privileges. It was in this context that more than 500 Franco-Mauritian and British settlers volunteered for the war while a labor battalion of 1,700 Creoles, led by British regulars and Franco-Mauritian volunteers, served with imperial forces in Iraq. Laborers were in fact in greater demand at home in Mauritius. During the war, Britain was cut off from Central and Eastern European beet sugar and relied on plantations in Mauritius for its sugar supply. Sugar prices more than doubled and continued to rise through the early 1920s. While the Franco-Mauritian estates prospered, Indian peasants increased their income and bought small parcels of land to put under sugarcane cultivation. Indian merchants benefited from the war and extended their influence over trade on food and clothing. Wartime campaigns against endemic malaria did much to improve the health of Mauritians. It was only in 1923, when sugar prices collapsed, that the island began to experience economic difficulties.[14]

With a more diverse economy, a larger settler population and a much larger land mass, the Union of South Africa could afford to send many more troops and laborers to France. One of South Africa’s most famous units was the South African Native Labour Contingent which included 21,000 black African laborers recruited from throughout Southern Africa, including Bechuanaland, Basutoland and Swaziland. Members of the contingent served in France as lumberjacks, stevedores and construction workers from September 1916 to January 1918. As much as possible, they were kept apart from French civilians. They lived behind barbed wire in closed compounds that bore a close resemblance to the ones found at the diamond and gold mines in Kimberley and Johannesburg. At various points, laborers protested their treatment. The unit was most famous, though, for its involvement in a terrible accident. In February 1916, the S.S. Mendi was carrying 802 laborers to France. Just off the coast of England, the transport was rammed by another ship and sank, with a loss of 607 laborers, plus nine officers and non-commissioned officers and thirty-three crew members. A legend arose that while the ship was sinking, African men of many different backgrounds lined up on deck to perform a death-dance so that they could die a manful and culturally appropriate death that demonstrated pan-African unity. While this episode has been commemorated in paintings and speeches as a form of national sacrifice, it was not actually witnessed by any of the survivors.[15]

South African Soldiers in France↑

For white South Africans, a greater sense of unity grew out of the experience of their countrymen in France. In July 1915, the South African government began to form a brigade of white volunteers to serve in Belgium and France. Mainly consisting of English-speakers, they were trained in South Africa by British soldiers. In early 1916 the first components of the unit left for Egypt where they served with other colonial forces before being sent to France for the Somme offensive. The “Springbok Brigade,” as it was called, developed a peculiar style. Many volunteers traced their origins to Scotland so the soldiers dressed in kilts. They came to be known for singing in Afrikaans and Zulu while they cultivated a reputation as frontier marksmen. In France they were assigned to the British 9th Division, also known as the Scottish Division. During 12-15 July 1916, at the height of the Battle of the Somme, the Springboks were deployed to the front lines. The brigade attacked heavily fortified German positions at Delville Wood and the nearby town of Longueval. With artillery support, the 3,150 South Africans surged forward and found the Germans staging an orderly retreat. The Springboks secured their position as best as they could – it was especially difficult to dig trenches in the woods where tree roots got in the way of shovels. On 15 July, the South Africans were counter-attacked by a German force more than twice their size. German artillery fire hit South African positions with pinpoint accuracy, shredding trees and turning the woods into a storm of splinters. Communications and re-supply became extremely difficult. The battle raged for five days, with reinforcements pouring in on both sides. On 21 July, the South African Brigade withdrew with only 779 soldiers left. The Springboks suffered approximately 750 deaths as well as 1,500 wounded, missing or captured. These were some of the worst casualties suffered by any British brigade during the war. Their sacrifice did foster a greater sense of unity among English-speaking white South Africans and showed that their country could make an important contribution on the world stage. While the brigade did go on to fight in other battles, most notably at Passchendaele in 1917, it was Delville Wood that cemented its reputation. The battlefield is today the site of the Delville Wood Memorial, designed by Sir Herbert Baker (1862-1946) and dedicated in 1926. The memorial commemorates 10,000 South African deaths in all theaters of the war, including South-West Africa and East Africa.[16]

Southern Africans and the Campaign in East Africa↑

It was in the dreadful East African campaign that Southern African soldiers and laborers made their greatest contribution. At the start of 1916, the British appointed Jan Smuts to command British forces in eastern Africa. Smuts did not have training as a professional soldier. From his experience as an officer in the South African War of 1899-1902, he was familiar with the long-standing method of Boer warfare: the “commando” in which horsemen rode to the scene of battle, dismounted, fired, remounted and maneuvered. This type of formation, also called “mounted infantry,” was particularly well-suited to the terrain and the subtropical climate of South Africa. However, Smuts’ decision to rely on mounted Europeans for the campaign against Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck’s (1870-1964) African soldiers was disastrous for reasons that have much to do with two diseases which are prevalent in Tanzania and the other countries of central and eastern Africa: malaria and trypanosomiasis, or sleeping sickness. The first debilitates and kills people, the second debilitates and kills people and their animals, including horses and cattle. Children in malarial regions die in great numbers but those who survive and who continue to be exposed to the mosquitoes that spread the disease develop some resistance. Lettow-Vorbeck’s African soldiers had some resistance, while the Europeans under Smuts did not. British forces labored under the further disadvantage of understanding how to prevent these diseases less well than their German opponents. Smuts was sufficiently wedded to ideas about the superiority of Europeans that he did not initially consider the use of African troops himself, although later in the campaign African soldiers contributed significantly.[17]

Conditions in Eastern Africa brought manpower issues to the forefront. At the start of his 1916 campaign, Smuts had available 70,000 soldiers to him, including units from the Belgian Congo, Portuguese Mozambique and British Kenya as well as South Africa. Lettow-Vorbeck commanded 16,000 troops, most of them “askari.” Smuts captured the ports of German East Africa and waged a far-ranging campaign against the much smaller German force. By January 1917, when Smuts left East Africa to become a member of the War Cabinet in London, most of German East Africa was under nominal British control, satisfying Smuts’ imperialist ambitions. Nonetheless, German forces were still at large, proving that German imperialism still had some vitality.[18]

The German campaign showed that the Portuguese in Mozambique were quite vulnerable. The two countries went to war officially in March 1916. Portugal dispatched 5,000 poorly armed and poorly trained soldiers to Mozambique to defend the border with German East Africa and to take an area on the border known as the Kionga Triangle. In September 1916, cross-border fighting resulted in more than a thousand Portuguese deaths and political embarrassment. Portuguese reinforcements were sent yet could not prevent another German invasion in November 1917. The forces of Lettow-Vorbeck entered Mozambique and neighboring colonies almost at will.[19]

The British and South Africans, together with their Portuguese allies, met with little success. In 1917, Smuts was replaced first by a British major-general, Reginald Hoskins (1871-1942), commander of the King’s African Rifles, who understood local conditions better than Smuts and worked to replenish his exhausted forces. In June, acting on the advice of Smuts, the British government mistook rebuilding for inaction and replaced Hoskins with Jacob van Deventer (1874-1922), an Afrikaner amateur like Smuts. Unlike Smuts (and like Hoskins), van Deventer was less interested in territorial expansion and more interested in destroying German forces.

German officers continued their guerrilla campaign and pillaged African villages and raided Portuguese and British bases for much-needed supplies. Portuguese and British efforts failed repeatedly to capture or eliminate the Germans. In the final weeks of the war, with little more than 100 German soldiers and 1000 African askari remaining under his command, Lettow-Vorbeck crossed into Northern Rhodesia. There, the British South Africa Company had presided over several years of strain and privation; now the appearance of the Germans began to inspire a revolt that was only averted because the war ended in Europe. Lettow-Vorbeck was obliged to surrender on 25 November.

The East African campaign had a devastating effect on local economies. More than 270,000 men were conscripted in North-Eastern Rhodesia alone, with thousands taken from the other British colonies as well as Portuguese Mozambique. Laborers in military service died at the rate of 2 percent every month. Villages emptied of men suffered from hunger and disease as crops were not cultivated and sleeping sickness spread. Conditions were worsened by the influenza epidemic of 1918 and even by an outbreak of plague. To add insult to injury, wartime inflation persuaded colonial rulers to impose higher taxes. The stricken people of the region became so destitute that many were seen wearing animal skins and tree-bark.[20] As Africans starved, the small German force challenged the British Empire and South African forces on the battlefield.

The East African campaign taxed manpower reserves throughout Southern Africa, thanks in large part to environmental conditions. The presence of tsetse flies and sleeping sickness necessitated the use of African porters, even though porters and soldiers alike succumbed in great numbers to malaria and intestinal diseases. The British Empire deployed a total of 110,000 soldiers to East Africa, many of them recruited from Uganda, Kenya and Nyasaland, as well as from the ranks of African soldiers who had fought for the Germans. The South African government refused to allow its own African men to serve as soldiers, except for the 1st Battalion of the Cape Corps, which spent most of 1916-1917 in the theater and lost 165 men. Out of the total number of African soldiers, over 10,000 died, mostly from disease. A total of 1 million porters were recruited from all around Eastern and Southern Africa and these, too, died at approximately the same rate of 10 percent with about 100,000 total deaths.[21]

Conclusion↑

The First World War did not persuade the indigenous people of Southern Africa of the beneficence of colonial settlers, administrators and soldiers. Nor did it serve the purpose of producing a greater sense of unity in any of the colonies, except among some white settlers in South Africa. Some of these would try to remember the war as a meaningful sacrifice but for most Southern Africans who died, this was not the case. The war exacerbated social patterns in Africa that were already familiar from the mining revolution and the imperial conquests of the late 19th century. While men left home, basic production was done increasingly by women as well as by children and the elderly. Cities expanded as wartime job opportunities arose. Certain industries, such as diamond mining, were disrupted. Gold mining continued, even if under strain, while farming experienced growth and manufacturing boomed. Prices rose, which fostered unrest and even strikes and rebellions in some places.

Many Southern Africans, like many Europeans, hoped that enduring wartime circumstances might bring them benefits when the war was over in the form of greater freedom and prosperity. In general, these hopes were not satisfied. Grundlingh points out that conventional interpretations of the war in Europe and the United States emphasize the ways in which wartime stresses led governments and ruling classes to rely more heavily on working classes, thus giving the working classes more opportunities and leverage. In Southern Africa, the colonial system of segregation and exploitation remained largely unchanged.[22]

William Kelleher Storey, Millsaps College

Section Editors: Melvin E. Page; Richard Fogarty

Notes

- ↑ Trapido, Stanley: Imperialism, Settler Identities, and Colonial Capitalism: The Hundred-Year Origins of the 1899 South African War, in Ross, Robert / Mager, Anne Kelk / Nasson, Bill: The Cambridge History of South Africa, 1885-1994. Volume 2, Cambridge 2010, pp. 66-101.

- ↑ Marks, Shula: War and Union, in: Ross / Mager / Nasson, The Cambridge History of South Africa 2010, pp. 157-210.

- ↑ Vail, Leroy: The Political Economy of East-Central Africa. In: Birmingham, David / Martin, Phyllis (eds.): History of Central Africa. Volume 2, New York 1983, pp. 205-209.

- ↑ Freund, Bill: South Africa: The Union Years, 1910-1948 – Political and Economic Foundations, in: Ross / Mager / Nasson, The Cambridge History of South Africa 2010, pp. 211-253.

- ↑ Nasson, Bill: Springboks on the Somme: South Africa in the Great War, 1914-1918, Johannesburg 2007, pp. 35-59.

- ↑ Baranowski, Shelley: Nazi Empire: German Colonialism and Imperialism from Bismarck to Hitler, Cambridge 2011, pp.46-60; Madley, Benjamin: From Africa to Auschwitz. How German South West Africa Incubated Ideas and Methods Adopted by the Nazis in Eastern Europe, in: European History Quarterly, 35/3 (2005), pp. 429-464.

- ↑ Portugal was allied with Britain but did not declare war on Germany until March 1916.

- ↑ Nasson, Springboks on the Somme 2007, pp. 63-87; Strachan, Hew: The First World War in Africa, Oxford 2004, pp. 61-92. A more extensive account is available in the article entitled South African Invasion of German South West Africa (Union of South Africa)

- ↑ Cruise, Adam: Louis Botha’s War. The Campaign in German South-West Africa, 1914-1915, Cape Town, 2015.

- ↑ Page, Melvin E.: The Chiwaya War: Malawians and the First World War, Boulder 2000; Strachan, First World War in Africa 2004, pp. 93-184; Nasson, Springboks on the Somme 2007, pp. 157-161.

- ↑ Stapleton, Timothy J.: No Insignificant Part. The Rhodesia Native Regiment and the East Africa Campaign of the First World War, Waterloo 2006, pp. 19-52.

- ↑ Gontard, Maurice: Madagascar pendant la première guerre mondiale, Tananarive 1969; Razafindranaly, Jacques: Les soldats de la grande île. D’un guerre à l’autre, 1895-1918, Paris 2000; Fogarty, Richard S.: Race and War in France. Colonial Subjects in the French Army, 1914-1918, Baltimore 2008, pp. 39-40, 65, 67, 89-90.

- ↑ Mitchell, B.R. (ed.): International Historical Statistics. Africa, Asia, and Oceania 1750-1993, Third edition, London 1998, pp. 525-528.

- ↑ Toussaint, Auguste: History of Mauritius. W. E. F. Ward (trans.), London 1977, pp. 84-88. Simmons, Adele: Modern Mauritius: The Politics of Decolonization, Bloomington 1982, pp. 29-32.

- ↑ Nasson, Springboks on the Somme 2007, pp. 157-170; Clothier, Norman: Black Valour: The South African Native Labour Contingent, 1916-1918, and the Sinking of the Mendi, Pietermaritzburg 1987, pp. 58, 72; Grundlingh, Albert: Mutating Memories and the Making of a Myth: Remembering the SS Mendi Disaster, 1917-2007, in: South African Historical Journal 63/1 (2011), pp. 20-37.

- ↑ Nasson, Springboks on the Somme 2007, pp. 123-156.

- ↑ Strachan, First World War in Africa 2004, pp. 123-125.

- ↑ For further details, please see the articles in this encyclopedia on East and Central Africa and South Africa and the German East Africa Campaign.

- ↑ De Meneses, Filipe Ribeiro: Portugal, 1914-1926: From the First World War to Military Dictatorship, Bristol 2004, pp. 39-47.

- ↑ Vail, Political Economy of East-Central Africa 1983, pp. 230-231.

- ↑ Nasson, Springboks on the Somme 2007, pp. 89-122, 157. Strachan, First World War in Africa 2004, pp. 93-184.

- ↑ Grundlingh, Albert: Fighting Their Own War: South African Blacks and the First World War, Johannesburg 1987, pp. 168-71.

Selected Bibliography

- Baranowski, Shelley: Nazi empire. German colonialism and imperialism from Bismarck to Hitler, Cambridge; New York 2011: Cambridge University Press.

- Clothier, Norman: Black valour. The South African Native Labour Contingent, 1916-1918, and the sinking of the Mendi, Pietermaritzburg 1987: University of Natal Press.

- Farwell, Byron: The Great War in Africa, 1914-1918, New York 1986: Norton.

- Gontard, Maurice: Madagascar pendant la première guerre mondiale, Tananarive 1969: Éditions universitaires.

- Grundlingh, Albert M.: Mutating memories and the making of a myth. Remembering the SS Mendi disaster, 1917-2007, in: South African Historical Journal 63/1, 2011, pp. 20-37.

- Grundlingh, Albert M.: Fighting their own war. South African Blacks and the First World War, Johannesburg 1987: Ravan Press.

- Killingray, David: The war in Africa, in: Horne, John (ed.): A companion to World War I, Chichester; Malden 2010: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 112-126.

- Marks, Shula: War and union, 1899-1910, in: Ross, Robert / Mager, Anne Kelk / Nasson, Bill (eds.): The Cambridge history of South Africa, 1885-1994, volume 2, Cambridge 2011: Cambridge University Press, pp. 157-210.

- McLaughlin, Peter: Ragtime soldiers. The Rhodesian experience in the First World War, Bulawayo 1980: Books of Zimbabwe.

- Meneses, Filipe Ribeiro de: Portugal 1914-1926. From the First World War to military dictatorship, Bristol 2004: Hiplam.

- Nasson, Bill: Springboks on the Somme. South Africa in the Great War, 1914-1918, Johannesburg; New York 2007: Penguin.

- Page, Melvin E.: The Chiwaya war. Malawians and the First World War, Boulder 2000: Westview Press.

- Page, Melvin E. (ed.): Africa and the First World War, New York 1987: St. Martin's Press.

- Razafindranaly, Jacques: Les soldats de la Grande île. D'une guerre à l'autre, 1895-1918, Paris 2000: L'Harmattan.

- Ross, Robert / Mager, Anne Kelk / Nasson, Bill (eds.): The Cambridge history of South Africa, 1885-1994, volume 2, Cambridge 2011: Cambridge University Press, online: http://public.eblib.com/EBLPublic/PublicView.do?ptiID=713027 (Retrieved 2014-08-13 12:09:18).

- Simmons, Adele: Modern Mauritius. The politics of decolonization, Bloomington 1982: Indiana University Press.

- Storey, William Kelleher: The First World War. A concise global history (2 ed.), Lanham 2014: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Strachan, Hew: The First World War in Africa, Oxford; New York 2004: Oxford University Press.

- Toussaint, Auguste: History of Mauritius, London 1977: Macmillan.