Introduction: From Peace to War↑

Russia entered the Great War while confronting the fundamental challenges of industrialization and modernization. Her vast peasantry, freed from serfdom in 1861, hovered somewhere between waxing private land ownership and traditional communal holdings. The expanding industrial economy beckoned rural dwellers to the cities, where new workers hung between city and village life. Many maintained membership in their village communes and some (in waning numbers) still travelled back and forth with the seasons. Russia’s middle classes, always more abundant than commentary has recognized,[1] rapidly expanded in size, self-awareness, and assertiveness, and challenged the entrenched privilege of the Russian nobility in terms of their wealth, and the monopoly that the nobility held over the officer corps and bureaucracy. Most tellingly, the most active noble families were transforming themselves into an educated professional and business class, or in other words, into the upper middle class. Russia indisputably entered the war with a society in extreme flux, with numerous social issues neither solved nor addressed. Even so, economic historians have pointed out that real wealth among all population segments was growing. Without major military conflict, Russia’s path could have been (and has been) evaluated as positive rather than negative, her problems associated with waxing growth and change, rather than with the too freely deployed concept of “backwardness.”

Social conflict is defined here as 1) manifestations of conflict between or among classes, or 2) anti-government or anti-war sentiment connected to social class or ethnicity. During the months prior to the war, the most obvious realm of social conflict concerned industrial workers who for over two years had engaged in strike action and demonstrated against the regime and its perceived partners, namely, the entrepreneurs, and proprietors of the industries where, in the workers‘ view, they labored for long hours for inadequate pay. Even so, simple class conflict does not wholly account for the pre-war situation. With the complicity of revolutionaries, workers did partake in protests and strikes, however, less well known is that Russia’s pre-war bourgeoisie, and the political parties that represented them, showed considerable sympathy for the workers’ welfare. For example, they bitterly criticized the government for the Lena Goldfields massacre of workers (April 1912), supported the 1912 workers’ health insurance law, and often urged the government in the newspapers to ameliorate the plight of the workers’, at a time when the regime itself aggressively pursued repression rather than accommodation.[2] These circumstances problematize over-simplified depictions of the era’s social problems.

The outbreak of total war altered the conditions of Russian life for many, as was the case in other involved nations. The government utilized patriotism in the early phases of the war to suppress worker unrest and, at the same time, drove socialist parties, their newspapers, and numerous labor unions, as well as other worker-oriented organizations, out of existence or deep underground. The strike movement of 1912-1914 abruptly halted with the outbreak of the war and socialist commentators noted that anti-government and anti-war propaganda began to be met with hostility, or at least fell on deaf ears. As the war approached, peasant unrest was at a low level and, with a few exceptions during early mobilization, remained so for the war’s duration.[3] For roughly a year, the exigencies of war wrought social peace or a facsimile thereof.

From Social Peace to Social War↑

High casualties, inflation and food shortages, the massive mobilization of workers and peasants, the government’s perceived incompetence, and the tsarist family's unpopularity shattered the fragile social peace. Many gradually disconnected patriotism for Russia from loyalty to the regime. By summer of 1915, socialists inside and outside the factories noticed a growing openness to anti-government agitation, which prompted greater efforts to reach urban laborers, peasants, and soldiers.[4] Anti-war Social Democrats, Socialist Revolutionaries, and anarchists, repeated certain themes in oral and printed materials throughout the empire and at the fronts. They proclaimed (in composite):

The growing wave of worker strikes and demonstrations throughout Russia leading up to the February Revolution (from roughly 35,000 strikers during July-December 1914 to almost 1,200,000 during 1916 and nearly 250,000 during January 1917) suggest that these proclamations were carefully listened to.[6]

From mid-1915 on, a deep class cleavage fractured Russian society. The issues that split society concerned attitudes towards the war and the government presiding over it. Russia’s nobility, the entrepreneurial and professional bourgeoisie, and considerable segments of the intelligentsia, supported the government and the war. On the other hand, over time workers, peasants (in the military and in the village), and the radical intelligentsia, opposed the war and held the government responsible for 1) entry into the war, 2) the poor conduct of the war, and 3) the tightening wartime repression. The issue’s complexity goes further. A significant numbers of peasants and soldiers, along with portions of Russia’s working classes, and parts of the radical intelligentsia, remained patriotic and/or hesitated to back the idea of revolution during the war. Many asserted the desire to settle with the tsarist regime after the war. Later on, especially by mid-1916, many normally patriotic Russians came to support the downfall of the tsarist regime - or at least of Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia (1868-1918) - on the premise that another more popularly based government would more effectively pursue the war effort. The “defeatism” of Vladimir Lenin (1870-1924), and some radical Socialist Revolutionaries, remained an abstract strategy rather than a template for revolutionary propaganda (public calls for Russia’s “defeat” did not occur). Even theoretical discussions construed “defeat” as the defeat (and downfall) of Russian tsarism rather than of the Russian nation at the hands of her foes.[7] The anti-war socialist slogan “Turn the international war into a civil war” exemplified this approach.

Wartime Workers↑

This complex web of attitudes towards the war found its best illustration in the campaign to create workers’ committees in association with the War-Industries Committees (WICs). WICs were instituted in mid-1915 as an entrepreneurial initiative to aid the government in its initially ineffective efforts to increase military production. The concept of organizing WIC workers’ committees spurred a huge debate among socialists and workers. Naturally, patriotic worker and socialist elements backed the idea of coordinating worker-entrepreneurial efforts, whereas anti-war socialists divided into two groups: those who opposed the idea outright and those who wished to create the workers’ groups as a (in this case legal) forum for anti-war, anti-government, and anti-capitalist discussions. After lengthy discussions, workers’ groups united in factories and cities throughout Russia’s industrial regions. As some had predicted, their official status allowed the election campaigns for WIC workers’ groups and the elected groups themselves to serve as forums for open expression of opinion and, often, condemnation of the government and the war, whereas patriotic voices were lost in the rising chorus of revolutionary sentiment.[8] The radical nature of the debates is illustrated by the mandate given by one large Petrograd plant to its designated participants in an upcoming conference of worker delegates to the WIC workers’ groups: “The conference is illegal. ...We have only come in order to announce in the name of the organized proletariat ... [that we will] take part in no voting in order not to give any grounds to maintain that we recognize the conference as legal.” At the conference itself (November 1915), a moderate socialist who favored the workers’ groups proclaimed: “You should announce that [until the summoning of an All-Russian Workers’ Congress] we are against taking part in the defence of Russia...We must counterpose our organizations to those of the bourgeoisie and the Black Hundreds [extreme rightist organizations, meant here to signify the nobles].”[9] In no other public organization in wartime Russia could such rhetoric be heard. By no means did all workers or WIC workers group members share these extreme views: some workers were patriotic and wished to delay revolutionary activities until after the war, and WIC workers groups in some localities functioned as originally intended. Worth mentioning in this regard is that literate workers (and peasants) who entered the armed forces had opportunities for advancement and workers in some war-related industries were draft exempt and received wage increases that outran inflation. Nonetheless, very few workers supported tsarism and their public and private discourse turned steadily against the war, a reality that opened up the potential for increasingly anti-government stances as the war dragged on.

Wartime Peasants and Soldiers↑

Although somewhat more difficult to discern and measure, the peasantry’s attitudes towards the war and regime also played a role, which was perhaps the most crucial role of all. Endemic peasant unrest between 1901 and 1908, along with widespread soldiers’ revolts (most of Russia’s armed forces consisted of drafted peasants) during 1906-1907, weakened the tsarist regime’s cherished idea of peasant loyalty. Even so, with their usual fortitude, peasants for the most part calmly faced the outbreak of war; the drafting of endless lines of young males, and the burden of fighting at the fronts under the harsh conditions of supply shortages and heavy casualties. By mid-1916, this staunchness began to waver - not, however, in terms of peasant unrest in the village. With massive numbers of peasants in uniform at the front and in garrisons all over Russia, villagers tilling the soil would hardly punish their own family members and co-villagers by sabotaging food production. Despite the mass drafting of horses for military usage, conscientious toil plus favorable weather led to adequate wartime harvests until 1917’s shortfalls (earlier perceived shortages reflected transportation problems and the diversion of foodstuffs to the fronts).[10]

The shift in peasant attitudes appeared in a different way - in waxing soldier unrest at the fronts and in garrisons throughout Russia, keeping in mind that the vast majority of soldiers were of peasant origin, as were most workers. It was, in the end, a soldiers’ mutiny in Petrograd garrisons that on 27 February (12 March - New Style) 1917 transformed worker and student demonstrations into an overthrow of the regime. Especially during 1916 and early 1917, anti-war and anti-regime propaganda appeared widely at the fronts, not to mention garrisons where access was easier. In mid-1916 the Northern Front army headquarters reported that: “propaganda of all socialist parties has intensified considerably. ...The aim is to convince the troops to stop the war and fight the government.” One leftist socialist at a September 1916 Moscow WIC workers’ group conference proclaimed: “Let government spokespersons conceal the unrest throughout the armed forces ...neither workers nor soldiers are deceived.” Indeed, by early 1917 the commanding general of one front characterized his armies as “pitiful nests of propaganda.“[11] The result was the soldiers’ revolt in Petrograd and the joy with which frontline soldiers, who had already often ceased obeying officers’ orders, received the news of tsarism’s fall.

Wartime students and intelligentsia↑

Students, especially at universities, technical schools, and gymnasiums (high schools for students preparing for the university) also played a role. Their history has not yet received serious attention and, of course, strictly speaking they were not a class. By the 1900s they issued from a variety of social backgrounds and, upon graduation, would have further filled the ranks of Russia’s burgeoning middle and upper-middle classes. Patriotic monarchist and liberal student groups existed and organized pro-government demonstrations in an around schools during the war, although socialist groups, despite government repression, had greater success as suggested by the size and number of their demonstrations, not to mention early and massive student involvement in the late February disturbances in Petrograd.[12] This too was natural: continuation of the war confronted male students with entry into the army for a cause that many felt was lost, for a government they did not trust.

Closely related to Russia’s students were the Russian intelligentsia, a term that signified educated persons (regardless of social background) who were critical of the tsarist regime. Institutions of higher learning served as training grounds (both with regard to education proper and initiation into revolutionary politics) for the radical intelligentsia. Here the story is less clear. Much of the intelligentsia of the capitals and other large cities tended toward wartime patriotism and wished to delay revolutionary work until after the war’s end, a stance with unclear potential since victorious tsarism would be, if anything, more assertive and less susceptible to overthrow.[13] Even so, this group provided numerous staunch critics of government and war of all radical tendencies. Eventually, the intelligentsia’s tolerance of the wartime tsarist regime waned as by late 1916 most persons of this status pushed for an overthrow of the regime in favor of a democratic government, which, presumably, some still felt would more effectively wage war.

Ethnicity and Class: a dangerous intersection↑

Recent scholarship has noted the relative success of the late Tsarist regime in establishing a modicum of ethnic and religious tolerance for the empire’s minorities. For instance, the non-ethnic designation Rossisskii had already begun to supplant the ethnic term Russkii in the official lexicon and all political parties to the left of the small anti-Semitic Black Hundreds and Nationalists, had planks in their programs condemning racial and religious discrimination. Consequently, at the war’s outbreak, leaders of non-slavic and non-Orthodox communities adhered to the idea of a multi-ethnic Russian state and urged participation in the mobilization and support for the government in its war efforts.[14] Most populations acquiesced. This did not, however, alter the reality that over the long term the Russian state’s intolerance, as evidenced by its earlier harsh Russification programs, had yielded a steady stream of non-slavic recruitment into revolutionary activism. Alongside Slavs, revolutionary parties contained numerous persons of Baltic, Polish, Armenian, Georgian, Tatar, and, above all, Jewish descent.

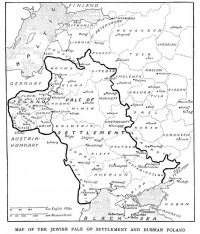

Because of their numbers and positions in their respective parties, Jewish revolutionaries are of special note. By law, Jewish populations, excepting only individuals of high education and wealth, found themselves restricted to the Baltic provinces, Poland, and, of course, Belorussian and Ukrainian territories, where they also suffered from periodic pogroms (violent and often deadly anti-semitic attacks). Further laws restricted them from farming and set quotas for their acceptance into universities. Consequently, most young Jewish men and women had limited options: become tradespersons or, more frequently, laborers in industry. Like other workers throughout the Russian Empire, they also entered anarchist, Social Democratic, and Socialist Revolutionary parties, not to mention the ethnic-oriented Bund (Jewish Social Democrats) and Zionist-Socialists. Operating under double repression - as Jews and as workers - their special dedication to the radical cause often resulted in their rise to leadership positions in disproportionate numbers, an unintended consequence of the Tsarist regime’s anti-semitic policies. Like others, initially many Jewish socialists took a patriotic stance by supporting the government, or at least not actively agitating against it until the war’s end.[15] Later, when sentiment among workers hardened against the government, Jewish activism, like that of other radicalized minorities, weighed heavily on the regime.

The February Revolution: Russia's last social consensus↑

During the year before the February Revolution any semblance of societal cohesion disappeared. A last attempt, led by the Progressist Block, a coalition of liberal and moderate parties with ties to socialist groups, to create broad social consensus by creating a government based upon the State Duma (Russia’s elected legislative body), also faltered This was primarily because of a lack of nerve on the part of moderate Duma leaders to act precipitately during wartime, and a deep-seated (and justified) fear of the revolutionary left’s hold over large segments of the population. As post-February 1917 events would reveal, a genuinely parliamentary government (either with or without a constitutional monarchy) also would have found it difficult to establish the modicum of social consensus necessary to govern. But the rise to power of the State Duma prior to the regime’s overthrow would unquestionably have altered the political-social equations, with unpredictable, perhaps favorable, results. This, of course, did not occur and instead of agreement on a parliamentary government, a different consensus swept across all class lines - the desire to replace Russia’s rulers: Nicholas II of Russia and his wife Alexandra Feodorovna, Empress, consort of Nicholas II (1894-1917), along with the ministers they had appointed. Unfortunately, just below this consensus lay utter disagreement about everything else. Should Russia have a constitutional monarchy or none at all? Should Russia strive for victory in the war, take a non-active role in the war, or resign from it entirely? Should Russia move on to a peasant-worker government with socialist leadership, or establish a government upon West European models?

Deciding Russia’s Future↑

In reality, the overthrow of the Tsarist regime on 27 February 1917 (12 March—New Style) exhausted the consensus. The Provisional Government (a carefully crafted liberal-moderate socialist compromise consisting mostly of liberal politicians) received a tentative mandate to govern until the summoning of a Constituent Assembly. Radicals, including Left Socialist Revolutionaries, Bolsheviks, other leftist Social Democrats and anarchists in Petrograd began at once to call for its end in favor of a government of laborers based upon soviets (elected councils). Most observers at first deemed this an insignificant (and shameful) phenomenon among a handful of malcontents. The wave of exultation at the regime’s overthrow seemed to promise the rise of a democratic Russia on the basis of multi-class compromise. Even so, within a month all the above mentioned disagreements about the war and Russia’s future, unresolved and unaddressed by the late February compromise, rose inevitably to the fore. Like the conservatives they had replaced, liberals and moderate socialists in and around the Provisional Government wanted to lead the country to a victory over her wartime enemies; unlike the conservatives, they also wanted to lead the country toward membership in the cohort of parliamentary states. Regardless, workers, peasants, soldiers, students, and the radical intelligentsia wanted instead to build a socialist government that promised human equality and viewed the war as the principal obstacle.[16] Pre-February stances on the war and the idea of a revolution during the war delineated post-February positions, with class largely designating where one stood along both the old and new barricades. Another revolution loomed and a civil war that would eventually decide Russia’s future.

Michael S. Melancon, Auburn University

Section Editors: Boris Kolonit͡skiĭ; Nikolaus Katzer

Notes

- ↑ Dowler, Wayne: Russia in 1913, DeKalb 2010, pp. 95-97 provides a discussion of the historiographical problem of Russia’s allegedly “missing” middle classes.

- ↑ Melancon, Michael: Unexpected Consensus: Russian Society and the Lena Massacre, April 1912, in: Revolutionary Russia 15/2 (2002), pp. 1-52; and McReynolds, Louise: The News Under Russia’s Old Regime, Princeton 1991, especially pp. 224-225, 248-251, and 286.

- ↑ Melancon, Michael: The Socialist Revolutionaries and the Russian Anti-War Movement 1914-1917, Columbus 1990, pp. 54-74, 158-163; Kir’ianov, Iu.: Sotsial’no-politicheskii protest rabochikh Rossii v gody Pervoi mirovoi voiny (iiul’ 1914 – fevral’ 1917 gg.) [Socio-political protest of Russian workers during the years of the First World War (July 1914 – February 1917)], Moscow 2005, pp. 13-14; Kir’ianov, Iu.: Rabochie iuga Rossii 1914 – fevral’ 1917 [Workers of South Russia 1914-February 1917), Moscow 1971, pp. 220-223; Retish, Aaron: Russia’s Peasants in Revolution and Civil War: Citizenship, Identity, and the Creation of the Soviet State, 1914-1922, Cambridge 2008, pp.26-28; Sanborn, Joshua: The Mobilization of 1914 and the Question of the Russian Nation: A Re-examination, Slavic Review, 59/2 (2000), pp. 274-278.

- ↑ Melancon, Socialist Revolutionaries, pp.74-111; Kir’ianov, Sotsial’no-politicheskii protest [Socio-political protest], pp. 19-23; Kir’ianov, Rabochie iuga [Workers of South Russia], pp. 223-276.

- ↑ See Melancon, Socialist Revolutionaries, pp. 70, 104, 126.

- ↑ Kir’ianov, Sotsial’no-politicheskii protest [Socio-political protest], pp. 183-184.

- ↑ Melancon, Socialist Revolutionaries, pp. 19, 22-27, 77-78, 171, 176-179.

- ↑ Siegelbaum, Lewis: The Politics of Industrial Mobilization in Russia, 1914-1917, New York 1983, pp. 159-82; Melancon, Socialist Revolutionaries, pp. 91-100, 106, 198, 221.

- ↑ Melancon, Socialist Revolutionaries, pp. 96-97.

- ↑ Retish, Russia’s Peasants in Revolution, pp. 22-63; Antsiferov, Alexis: Russian Agriculture during the War, New Haven 1930, pp. 118-128, 142-150.

- ↑ Melancon, Socialist Revolutionaries, pp. 113-131; 217.

- ↑ Melancon, Socialist Revolutionaries, pp. 63-64, 109-110, 133-134, 222-223, 238-278; Atsarkin, A.: Zhizn’ i bor’ba rabochei molodezhi v Rossii 1900-1917 [Life and Struggle of Worker Youth 1900-1917], Moscow 1976, pp. 168-178.

- ↑ Melancon, Socialist Revolutionaries, pp. 62-70, 163-166; 192-195, 252-253.

- ↑ Sanborn, The Mobilization of 1914, pp. 267-89; Sanborn, Joshua: Drafting the Russian Nation: Military Conscription, Total War, and Mass Politics, 1905-1925, DeKalb 2003, pp. 74-82.

- ↑ Jahn, Hubertus: Patriotic Culture in Russia during World War I, Ithaca 1995, p. 113; Lohr, Eric: Nationalizing the Russian Empire: The Campaign against Enemy Aliens during World War I, Cambridge, MA 2003, pp.84-85, 140-142, 201n.

- ↑ Melancon, Socialist Revolutionaries, pp. 226-278; Melancon, Michael: Rethinking Russia’s February Revolution: Anonymous spontaneity or socialist agency, in: The Carl Beck Papers 1408 (2000); From the Head of Zeus: The Petrograd Soviet’s Rise and First Days, 27 February-2 March 1917, in: The Carl Beck Papers 2004 (2009).

Selected Bibliography

- Antsiferov, A. N. / Bilimovič, Aleksandr Dmitrievič: Russian agriculture during the war, New Haven 1930: Yale University Press.

- Antsyferov, Aleksei Nikolaevich / Bilimovich, Aleksandr Dmitrievich / Batshev, Mikhail Osipovich et al.: Russian agriculture during the war. Rural economy, New Haven 1930: Yale University Press.

- Atsarkin, Aleksandr Nikolaevich: Zhizn' i bor'ba rabochei molodezhi v Rossii. 1900-oktiabr' 1917 g. (Life and struggle of worker youth 1900-1917), Moscow 1976: Mysl'.

- Dowler, Wayne: Russia in 1913, DeKalb 2010: Northern Illinois University Press.

- Jahn, Hubertus: Patriotic culture in Russia during World War I, Ithaca 1995: Cornell University Press.

- Kir'ianov, Iurii Ilоich (ed.): Rabochie Iuga Rossii 1914-fevral' 1917 g. (The Workers of Southern Russia, 1914-February 1917), Moscow 1971: Nauka.

- Kir'ianov, Iurii Ilоich / Tiutiukin, S. V.: Sotsial'no-politicheskii protest rabochikh Rossii v gody Pervoi mirovoi voiny. Iiul' 1914 - fevral 1917 gg. (Socio-political protest of Russian workers in the years of the First World War. July 1914-February 1917), Moscow 2005: Institut rossiiskoi istorii RAN.

- Lohr, Eric: Nationalizing the Russian Empire. The campaign against enemy aliens during World War I, Cambridge 2003: Harvard University Press.

- McReynolds, Louise: The news under Russia's old regime. The development of a mass-circulation press, Princeton 1991: Princeton University Press.

- Melancon, Michael S.: Rethinking Russia's February revolution. Anonymous spontaneity or socialist agency?, Pittsburgh 2000: University of Pittsburgh.

- Melancon, Michael S.: The socialist revolutionaries and the Russian anti-war movement, 1914-1917, Columbus 1990: Ohio State University Press.

- Melancon, Michael S.: From the head of Zeus. The Petrograd Soviet’s rise and first days, 27 February-2 March 1917, in: The Carl Beck Papers in Russian and East European Studies/2004 , 2009, pp. 78.

- Melancon, Michael S.: Unexpected consensus. Russian society and the Lena Massacre, April 1912, in: Revolutionary Russia 15/2, 2002, pp. 1-52.

- Pearson, Raymond: The Russian moderates and the crisis of tsarism, 1914-1917, London; Basingstoke 1977: Macmillan.

- Retish, Aaron B.: Russia's peasants in revolution and civil war. Citizenship, identity, and the creation of the Soviet state, 1914-1922, Cambridge; New York 2008: Cambridge University Press.

- Sanborn, Joshua A.: The mobilization of 1914 and the question of the Russian nation. A reexamination, in: Slavic Review 59, 2000, pp. 267-289.

- Sanborn, Joshua A.: Drafting the Russian nation. Military conscription, total war, and mass politics, 1905-1925, DeKalb 2003: Northern Illinois University Press.

- Siegelbaum, Lewis H.: The politics of industrial mobilization in Russia, 1914-17. A study of the war-industries committees, New York 1983: St. Martin's Press.