The Creation of the Schutztruppe↑

“Schutztruppe” was the official name for the German colonial armed forces in the “protectorates” of German East Africa, German Southwest Africa and Cameroon. When the German Reich became a colonial power in 1884/85, no provision was made for the creation of national military formations in the German colonies. Chancellor Otto von Bismarck’s (1815-1898) idea was to have all instruments of power established and financed solely by the trading companies active in these territories. But the companies either refused to do so, as in Togo and Cameroon, or invested so little in their troops that these represented no serious power factor. In 1889, native resistance in East and Southwest Africa forced Bismarck to finally agree to the creation of a colonial troop force. Though financed by the state, these troops were organised under private law, for officially, the administration of both colonies still rested with the trading companies. All German members of the armed forces had to resign and sign contracts of employment directly with the commanders Hermann Wissmann (1853-1905) and Curt von François (1852-1931). After the so-called “Araber-Aufstand” (Abushiri Revolt) had been quelled and the German Reich had subsequently taken over the administration of East Africa, the “Wissmann-Truppe” was the first formation to be transformed into a “Kaiserliche Schutztruppe” (Imperial Protection Force) on 22 March 1891.

The original plans did not include a transformation of the police forces in Togo, established in 1885, or those in Southwest Africa and Cameroon, established in 1891. Increasingly frequent violent conflicts with native tribes, however, revealed the deficiencies of the existing instruments of power. Therefore on 3/4 May 1894 the Chancellor issued orders to re-organise all police forces in Southwest Africa and Cameroon after the model of the German East African Schutztruppe. The change of name was officially announced by Wilhelm II, German Emperor (1859-1941) on 9 June 1895. In 1894 the police force in Togo was also re-organised with the intention of transforming them into a Schutztruppe at a later date. But the planned transformation was delayed again and again and finally abandoned in 1900.

Organisation and Composition of the Schutztruppe↑

The Schutztruppe formed a third military branch alongside the army and the navy. As an institution of the Reich they were, like the navy, subordinate only to the supreme command of the Emperor. On the organisational and disciplinary level the Schutztruppe were at first attached to the “Reichsmarineamt” (German Imperial Naval Office) and on the administrative level to the Colonial Department of the Foreign Office. Conflicts over responsibility led to a transfer of the administration of all matters concerning the Schutztruppe to the Colonial Department in 1896 and then to the “Reichskolonialamt” (Colonial Office of the Reich) in 1907, while the Emperor ceded some of his authority to the Chancellor. Supreme commanders in the colonies were the governors. These were authorised to deploy the Schutztruppe as they saw fit for military purposes as well as for purposes of civil administration, though only after consultation with the respective commanders. The commanders of the Schutztruppe had the sole authority over all military matters such as training, discipline and equipment. This created a constellation, unusual in the German Reich, where an officer reported to a civil servant.

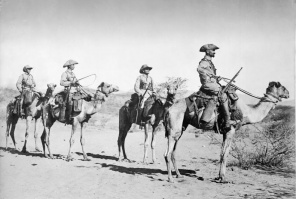

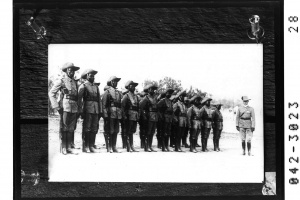

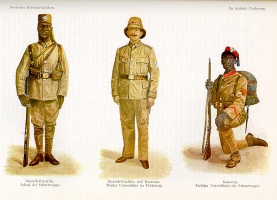

Modelled on the “Wissmann-Truppe”, the Schutztruppe in Cameroon and German East Africa were composed of German officers and non-commissioned officers as well as African soldiers. Because German Southwest Africa was the only German settler colony in Africa, however, the lower ranks of the Schutztruppe there consisted of German soldiers, too. All applicants for colonial service were volunteers who had to fulfil formal criteria such as being fit for the tropics and free of debt to be accepted. The term of service was two years in Cameroon, two and a half in East Africa, and three and a half in Southwest Africa. Service in the colonies was coveted because of the high pay and the chance to take part in combat and thus be promoted sooner and decorated with a medal.

During the 1890s, the African members of the Schutztruppe were primarily recruited in the colonies of other European powers; later the majority came from the colonies themselves. Most soldiers – called Askari in German East Africa – volunteered to join the colonial armed forces and enlisted for a specific period of time, usually between two and five years. The considerably higher potential earnings than in other occupations and their inherent social prestige attracted many African men to the profession of soldier. The soldiers had to subject themselves to a rigid discipline, though. Unlike common soldiers in the German Reich, Africans could be punished with beatings for the slightest offense, but this was not specific to the Schutztruppe. The racial hierarchy and corporal punishment that the African personnel under German command experienced were also common in other colonial armies in Africa, for instance in the British King’s African Rifles (KAR) or the Belgian Force Publique.

The Tasks and Strength of the Schutztruppe↑

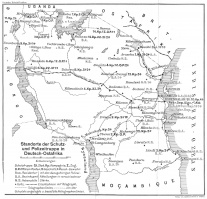

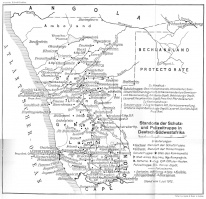

According to the “Schutztruppengesetz” (Schutztruppe Act), the Schutztruppe were supposed to guarantee “public order and safety” in the overseas territories – that is, to serve more or less as a police force – and to fight the slave trade (non-existent in Cameroon and Southwest Africa). In reality, though, the Schutztruppe’s main task in their early years was to extend the German territory, at first mostly limited to the coast, by force. The length of this stage of conquest varied in the three colonies: in German East Africa it lasted from 1891 to 1902, in German Southwest Africa from 1894 to 1903/04, and in Cameroon from 1894 to 1908. In order to achieve these objectives, the Schutztruppe had to wage a number of wars. The East African colonial armed forces alone undertook some eighty major subjugation campaigns between 1891 and 1902.

When the conquest phase was over, two major acts of resistance led to the biggest crisis in Germany’s brief colonial history. In January 1904, first the Hereros and then the Namas rebelled against the German colonial rule in German Southwest Africa; in 1905, around twenty tribes in East Africa followed suit. Both the Herero-Nama War and the Maji-Maji War ended only after massive reinforcements of the Schutztruppe arrived in Africa and years of heavy fighting. In response to these “rebellions”, extensive reforms were introduced, among them relieving the Schutztruppe of all administrative duties in 1906. In addition, the execution of minor retributive operations was delegated to the police forces existing in all colonies, while the Schutztruppe were to focus on enhancing their military capabilities. This included, in addition to an intensification of military training, the establishment of two permanent carrier corps in East Africa and Cameroon and the creation of a signals unit in East Africa.

The permanent state of war in the colonies forced the Reichstag in Berlin, which had to approve the Schutztruppe’s budget on an annual basis, to regular increase it. From a total of 736 Germans and 1,914 Africans serving in the three colonial armed forces in 1895, the numbers grew to 2,432 Germans and 4,122 Africans in 1914. In addition, in times of crisis the Schutztruppe could expect massive short-term reinforcements. During the Herero-Nama War, for example, at times more than 15,000 German soldiers fought in Southwest Africa.

Conduct of War of the Schutztruppe↑

As a rule, the Schutztruppe waged their wars against the native tribes with the utmost brutality and in contempt of international laws of armed conflict. The Schutztruppe generally made no distinction between combatants and non-combatants, which means that even women and children frequently became victims of the hostilities. Since the African tribes tended to avoid open battle, the Schutztruppe usually employed a scorched earth strategy. The idea was to force the opponents to surrender by the systematic destruction of their natural resources. During the Herero War in 1904, the Schutztruppe temporarily even practiced a type of genocidal war which killed between 65,000 and 80,000 people.

Despite their superior weaponry – equipment included, in addition to relatively modern breechloaders, machine guns and artillery – the Schutztruppe were frequently forced to accept defeat. On 17 August 1891, the colonial armed forces suffered the biggest disaster in their history when an expedition corps, commanded by Emil Zelewski (1854-1891) and consisting of three companies, ran into a Hehe ambush near Rugaro in German East Africa and was almost completely annihilated. Ten German officers and non-commissioned officers, including Zelewski, 291 Askari and ninety-six carriers died.

The Schutztruppe in World War I and Their Disbandment↑

Though national defence was not explicitly listed among the duties of the Schutztruppe, the German colonies, in case of war against another European colonial power, were not to be given up without a fight. Corresponding instructions for the event of war had been issued a few years before the outbreak of World War I, stipulating that the Schutztruppe, reinforced by African and German reservists, were to retreat fighting into the interior and maintain their positions there, if possible until the end of the war, which was not expected to last more than three months. It was hoped that this would improve the chances of regaining the colonies in possible peace negotiations.

All three branches of the Schutztruppe fought longer than expected. In German Southwest Africa, the Schutztruppe only surrendered to the South African troops, which outnumbered them, on 15 July 1915. Some border skirmishes whose outcome had been favourable to the Germans and the revolt of part of the Boer population in South Africa had delayed the attack on the colony by several months. In Cameroon, too, the colonial armed forces managed, by means of sporadic counter-attacks, to delay the advance of the Belgian, British and French units, whose attacks came from all sides but were often uncoordinated. The Germans profited from the difficult terrain of the country, which was a greater obstacle to the attackers than the defenders. When the main force of the Schutztruppe faced encirclement, they crossed the border into neighbouring, neutral Spanish-Guinea and let themselves be interned there in late February 1916.

In German East Africa, the commander of the local Schutztruppe, Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck (1870-1964), refused to follow the existing orders. He favoured open warfare and had the neighbouring Belgian and British colonies attacked immediately after the outbreak of the war. His intention was to force the Allies to transfer as many soldiers as possible from Europe to Africa to protect their overseas territories in order to relieve the German troops on the Western Front. This plan failed, however, since the Allies mainly deployed soldiers from the colonial territories in East Africa. By repelling a British attempt to land in the port of Tanga in early November 1914, the Schutztruppe were able to delay the invasion of German East Africa by almost a year and a half. In March 1916, the Allies started a new major offensive and finally managed to conquer the whole colony by November 1917. Still Lettow-Vorbeck refused to surrender and continued to fight in the neighbouring Portuguese and British colonies. Only when he learned of the end of the war on 13 November 1918 did Lettow-Vorbeck give up the fight.

After the German defeat in World War I and the ensuing loss of its colonies, Germany had no more need of a colonial armed force. On 10 November 1919, the Schutztruppe of Southwest Africa and East Africa were officially disbanded, and on 31 March 1920 the Schutztruppe of Cameroon was dissolved.

Thomas Morlang, Ruhr Museum, Essen

Section Editor: Michelle Moyd

Translator:

Selected Bibliography

- Bührer, Tanja: Die Kaiserliche Schutztruppe für Deutsch-Ostafrika. Koloniale Sicherheitspolitik und transkulturelle Kriegführung, 1885 bis 1918, Munich 2011: Oldenbourg.

- Hoffmann, Florian: Okkupation und Militärverwaltung in Kamerun. Etablierung und Institutionalisierung des kolonialen Gewaltmonopols 1891-1914, volume 2, Göttingen 2007: Cuvillier.

- Kuß, Susanne: Deutsches Militär auf kolonialen Kriegsschauplätzen. Eskalation von Gewalt zu Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts, Berlin 2012: Ch. Links Verlag.

- Morlang, Thomas: Askari und Fitafita. 'Farbige' Söldner in den deutschen Kolonien, Berlin 2008: Ch. Links Verlag.

- Moyd, Michelle: Violent intermediaries. African soldiers, conquest, and everyday colonialism in German East Africa, Athens 2014: Ohio University Press.