Biography↑

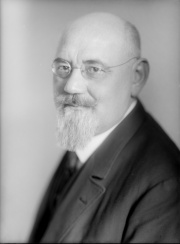

Karl Renner (1870-1950) was born on 14 December 1870 in Unter-Tannowitz in Moravia, then part of the Habsburg Empire. His father was a peasant, who in 1885 had to auction off his farm by public sale. The humiliation and pauperisation of his family had a formative influence on Renner. He studied law at Vienna University and finished his studies in 1898. During his studies he became active in the labour movement. Together with Otto Bauer (1881–1938) and Gustav Eckstein (1875–1916), he founded the theoretical social democratic monthly Der Kampf and became one of the leading theoreticians of Austro-Marxism. He was employed at the library of the Austrian Parliament (Reichsrat), where he reached the secure position of a civil servant. In 1907 he was elected as a Social Democrat to the Austrian parliament, representing the heavily industrialised constituency of Neunkirchen in Lower Austria.

Renner’s Position at the Beginning of World War I↑

On the eve of World War I Renner was one of the younger members of the Social Democratic Parteivorstand (National Executive Committee). The party leadership agreed to a policy of non-resistance to the war mainly for two reasons. The first was the fear that a Russian victory over Germany would mean a victory for Tsarist despotism. The second was the fear that open resistance would lead to the suppression of the labour movement, thus nullifying what the de facto party leader Victor Adler (1852–1918) and many others beside him considered as their life’s work.

Renner kept some distance from the openly Germanophile line of leading politicians and party journalists like Friedrich Austerlitz (1862–1931), Engelbert Pernerstorfer (1850–1918) and Karl Leuthner (1869–1944). According to Julius Deutsch (1884–1968), Renner was at first even counted among the oppositionist anti-war left, together with Friedrich Adler (1879–1960), Robert Danneberg (1885–1942), Gabriele Proft (1879–1971) and others. This position was also reflected in his first articles after the outbreak of the war in the party’s magazine, Der Kampf, in December 1914 and in speeches at internal party gatherings (Reichskonferenz). Renner deplored that the war had come about but argued that the party could not have done anything to stop it. He outlined his view that the task of the party leadership now was to defend the material interests of the proletariat and wait for better times. But this brief flirtation with the left opposition soon came to an end.

The Ablest Apologist of “War Marxism”↑

Renner’s stature grew as soon as he came around to a position that differed from both the anti-war left and the deutschnational (German national) right. His was not a nationalistic Pan-Germanism. Renner not only defended but celebrated the survival of the Habsburg Monarchy as the triumph of the Nationalverband (a community of nations) over the nation-state. Renner argued that the supranational Habsburg state had shown its superiority over the nation-state and he saw the war as the logical conclusion of a development of capitalism that would lead to a new society, where the role of the industrial workers would be enhanced. The tendency of the Habsburg state to intervene in the economy in wartime was doing the work of socialism. Renner expected this growing influence of the state on the economy (“Durchstaatlichung der Wirtschaft”) to continue after the war and concluded that this would be the form through which practical socialist aims could be achieved.

Though not as deutschnational as others in the party, Renner still looked up to German Kultur (and by extension also Austrian Kultur) as exemplifying a superior society compared to the alternatives to the west and east. Especially remarkable in this context are his attacks on the Entente Powers, whom he condemned as imperialists. Renner thus became the most important proponent of what the socialist theoretician Karl Kautsky (1854–1938) would later label “Kriegsmarxismus” (“War Marxism”). The rapprochement between the Social Democratic parties in Germany and Austria and the monarchical Hohenzollern and Habsburg states in Renner’s view was not a short-lived mariage de circonstance, but rather the truly Marxist road to socialism, avoiding both the Scylla of Russian despotism and the Charybdis of liberal-capitalist imperialism of the Western powers.

In the discussions on war aims in the Austrian Parteivorstand, Renner strongly supported annexations in the east, calling territories hitherto controlled by Russia Annexionsland (“land fit for annexation”). Renner also became one of the proponents of plans for a radical political and economic restructuring of Central Europe associated with Friedrich Naumann (1860–1919) and the catchphrase Mitteleuropa (Central Europe).

In October 1916, Renner was drafted into the military and served in an administrative function in the Ministry of War. In December 1916, Renner became member of the Office of the People’s Food Supply (Amt für Volksernährung). In June and August 1917, Renner was offered a ministerial post in the Austrian government by two successive prime ministers but declined both times after consulting the party’s executive.

The Lueger of Social Democracy?↑

In the middle of this development, the sensational murder of the Austrian Prime Minister Karl Graf Stürgkh (1859–1916) by Friedrich Adler on 21 October 1916 led to a change in the political climate of the Habsburg Monarchy that also gradually reduced Renner’s influence in the party. At his murder trial, Adler fiercely attacked Renner, singling him out as the symbol of the moral and political decay of Austrian socialism. He accused him of being “the Lueger of social democracy”, and thus invited comparison with the founder of Austrian political antisemitism, who had also been seen as an unprincipled opportunist by his adversaries.

At the party conference in October 1917, the first since 1913, Renner found himself in the role of the accused, criticized by the anti-war left, led by Proft and Danneberg. The conference ended in a compromise but showed the lingering resentment between anti-war and pro-accommodation-to-the-war delegates. Victor Adler’s party management skills carried the day, as he managed to placate the accommodationist majority without pushing the left opposition out of the party. This juggling act also meant that Renner, who for the anti-war left was the living embodiment of everything that was wrong with the party, had to be ever so subtly retired from too public a role as the voice of Austrian Social Democracy.

Renner’s Publications↑

Renner’s most influential works were Österreichs Erneuerung (The Renewal of Austria), a three-volume collection of articles from the Arbeiterzeitung and other newspapers published in 1916 by the party’s own publishing house, and Marxismus, Krieg und Internationale, published in 1917 by the German social democratic publishing house Dietz. Ironically, the latter was dedicated in its first edition to Otto Bauer, who would become the head of the left anti-war faction inside the party after his return from Russian captivity in autumn 1917 and a strong critic of Renner’s stance during the war.

Renner’s Role as Head of the New Republican Government↑

The gradual breakdown of the Habsburg Monarchy in the summer and autumn of 1918 brought Austrian Social Democracy into government for the first time in its history. On 21 October 1918, the members of parliament from mainly German-speaking constituencies of the old Reichsrat declared themselves to be the German-Austrian provisional national assembly. Victor Adler, though ailing, was at the forefront of negotiations and became Foreign Secretary. On the verge of death, Adler installed Otto Bauer as his second-in-command in the Foreign Office. As a member of the new German-Austrian executive branch, the Staatsrat (Council of State), Renner was nominated only to a seemingly secondary role as Leiter der Staatskanzlei (Head of the State Chancellery), officially tasked with taking the minutes of the Staatsrat but also part of its five-person executive committee (Staatsratsdirektorium).

Through sheer hard work Renner soon made himself indispensable. He turned his bureaucratic position into the role of chairman of the executive branch – the office of Staatskanzler (State Chancellor) was thus carved out by Renner during the autumn and winter of 1918/1919. Renner was also instrumental in formulating the National Assembly’s proclamation of the Austrian Republic on 12 November 1918 and its first provisional constitution. However, his influence in the party had already peaked. Momentum was now firmly with the anti-war left around Friedrich Adler, Otto Bauer, Robert Danneberg and centrists like Karl Seitz (1869–1950), who would go on to lead the party in the 1920s and 1930s but who had to tread a careful course – most members of the party elite had, like Renner, after all subscribed to a policy of compromise with the Habsburg state in the years from 1914 to 1918.

Paul Dvorak, Universität Wien

Section Editor: Tamara Scheer

Selected Bibliography

- Brügel, Ludwig: Geschichte der österreichischen Sozialdemokratie, volume 5, Vienna 1925: Wiener Volksbuchhandlung.

- Deutsch, Julius: Geschichte der deutschösterreichischen Arbeiterbewegung: Eine Skizze, Vienna 1922: Wiener Volksbuchhandlung.

- Hannak, Jacques: Karl Renner und seine Zeit: Versuch einer Biographie, Vienna 1965: Europa-Verlag.

- Nasko, Siegfried: Karl Renner: zu Unrecht umstritten? Eine Wahrheitssuche, Salzburg 2016: Residenz.

- Rauscher, Walter: Karl Renner: ein österreichischer Mythos, Vienna 1995: Ueberreuter.

- Saage, Richard: Der erste Präsident. Karl Renner - eine politische Biografie, Vienna 2016: Paul Zsolnay Verlag.