Introduction↑

Whenever possible, scholars of popular religion recapture the individual expressions of religious belief using inherently impressionistic or even pointillist portrayals.[1] Proper historical contextualization helps, but often quickly spreads into the realm of folklore, myth and superstition – or simply unverifiable anecdotes. Despite the inherent difficulties in trying to convey personal religiosity, one must attempt to better understand the mindsets of the individuals who lived through the conflict. In particular, one must examine popular religion beyond states’ instrumental intentions. For religious believers, existential questions of the human condition were not ultimately determined by whether their states won or lost the war.[2]

Historiographically speaking, much of the literature on popular religion concentrates on Christianity, though there are indications that this is changing. This article will reflect both the historiographic imbalance, as well as point the way toward future global developments. One can think of popular religion during the war as a model of concentric circles, with official organized religion as the center of the model. Thus, popular religion has both centripetal and centrifugal tendencies related to established institutions and practices.[3] Complicating narrative frameworks, the problematic secularization thesis causes interpretive difficulties for an assessment of popular religiosity during the war.[4] In the grand narrative of secularization, the Great War was a moment of hypermodernity, accentuating the disenchantment of the modern world that had begun in the Early Modern Era and the Age of Enlightenment: anything beyond rational materialism was simply a legacy of medieval superstition, out of place with large-scale social trends. Therefore, when discussing “culture,” there is a tendency to associate cultural representations with modern artistry and avant-garde culture.[5]

Nevertheless, one must reconcile avant-garde trends with popular beliefs and evolving traditions, recognizing that the Great War moved religious tradition both backward and forward in a complicated process.[6] In some ways, the Great War witnessed an incredible return to the past, deep into the archaic and primeval recesses of the human mind. Hellish, barren battlefields defied the imagination. People struggled to understand the conflict in any way they could. Rumors, myths, folklore, magic, metaphysics and legends were deeply embedded in cultures. Sometimes these practices had partially archaic and unknowable roots.[7] Thus, drawing on deep and sophisticated historiogaphies of popular religion, the ancient, medieval and early modern eras prove insightful when applied to the Great War’s mobilization of belief.[8] In other ways, however, the Great War moved religious tradition forward into new realms, such as the rise of the liturgical movement and youth movement in Catholicism or the rise of dialectical theology in Protestant circles.

One must also account for subjective perspectives and relativism. The use of the loaded term “superstition,” for example, depended greatly on context. For a committed rationalist, belief in anything metaphysical was classified as superstition; thus, in the minds of its opponents, the Catholic Church, for example, was a prime target. Within the context of Catholic tradition, however, “superstition” could mean any metaphysical belief outside of approved doctrine, such as when the Church condemned spiritualism as a form of black magic.

An analysis of popular religion during the Great War confronts an immense twofold problem: first, there is the issue of individual believers’ subjectivity, an attempt to “peer into hearts” that will always end at an impassable border.[9] Second, there is the problem of empirical evidence, for as Annette Becker has written:

Thus, the study of popular religion during the Great War presents special problems of evidence. Studies of churches and official religion can rely on more empirically accessible sources of public religiosity such as communion statistics, burial records, bureaucratic reports (from both military and religious administrative sources), and the written words of clerics in the public sphere. Above all, this last source has dominated religious histories of the First World War, written from top-down elite perspectives of clerics writing in a bellicose theology of “just war.” Studies of popular religion, however, must necessarily draw on a wealth of sources that do not lend themselves to empirical representation, and in some cases represent a single individual’s interpretation of events, viewed decades afterward and impossible to verify. Nevertheless, the presence of alternative narratives lends much strength to a more varied popular religious experience. Thus, the study of popular religion augments standard cultural representations of religion: beyond the views of either the established churches or religion’s cultured despisers.

Doubt↑

From the outset, one should acknowledge that religious mobilization and popular belief included the doubters and deniers, as well as those believers who were repelled by forms of public religiosity. At one extreme of the belief spectrum, the Great War reaffirmed atheism and caused some religious people to lose their faith entirely. Contrary to popular stereotypes of religion during wartime, there certainly were atheists in the foxholes. The immense horrors of battlefield carnage also caused religious soldiers to lose their faith. Believers on the home front lost faith, too, as their loved ones vanished and social suffering continued. The loss of belief was perhaps most starkly represented in the writings of soldiers close to mass death and destruction in battle. The archetypically horrific landscape of the Western Front trenches served as the potent symbol of a loss of faith, the shattered illusions of the pre-1914 world. Struggling to convey the impossible and wrestle with the possibility of God’s absence (or non-existence), the English artist Paul Nash (1889-1946) succinctly described his impressions of the trench setting:

On the other side of the trenches, the German expressionist poet Alfred Lichtenstein (1889-1914), killed in battle in the war’s opening months, wrote a “Prayer before Battle” which predated many of the war poets’ waning enthusiasm for war, satirizing the notion of religious believers praying for their own protection as well as the deaths of their enemies:

Such poetry also helped to delegitimize the notion of collective sacrifice. As Paul Fussell has argued, the teleological portrayal of movement was from “initial enthusiasm to final cynicism.” Fussell highlighted the case of the British writer Charles Edward Montague (1867-1928) and his aptly named memoir, Disenchantment. Using religious leaders as prime examples of corrupt authority and hierarchy, Montague wrote that, “in the first few weeks of the war, most of the flock had too simply taken on trust all that its pastors and masters had said.” Later, “they were out to believe little or nothing – except that in the lump pastors and masters were frauds.”[13] Montague wrote earthy descriptions of the de-glorification of war: “Battles have no aureoles now in the sight of the young men [who] … have seen the trenches full of gassed men, and the queues of their friends at the brothel-door in Béthune.”[14]

Besides the effect of rampant bodily destruction, extended human suffering could cause people to lose faith. Hunger, poverty and illness became highly visible public phenomena, especially in countries that were losing the battle of economic mobilization. As nothing seemed to intervene to stop the social suffering, people began to doubt the existence of a metaphysical reality, and more so the idea that Providence could favor their side.

Atheism was rarely officially acknowledged in official statistics and must be considered as part of the spectrum of more widespread public agnosticism. A survey of the British 38th Division’s nearly 15,000 troops identified only three self-proclaimed atheists. Similarly among the U.S. 82nd Division, only twenty-four out of 32,468 soldiers identified themselves as atheist. Personal narratives of individual’s religious attitudes were highly variable and should be contextualized in terms of their recoverable inner thought-worlds. In what Richard Schweitzer has described as the “making of an atheist,” for example, the British soldier Arthur Graeme West’s (1891-1917) highly personal journey to atheism took place over a long period of time. A few months before West’s death in combat in April 1917, he recorded as part of his spiritual odyssey:

Especially in light of repeated, sustained exposure to battle, such attitudes were dominant among modernist portrayals in literature and art, particularly among the literate middle and upper classes. While important, such attitudes will not be discussed further here, but these beliefs need to be relativized among an outpouring of other forms of popular religious belief.

Ideology and State Mobilization↑

The various combatant states used religious belief to muster support, harnessing enthusiasm for victory in an increasingly total war. Phrases as “Gott mit uns,” “Dieu est avec nous” became fiery slogans of exclusionary belief in the cause’s righteousness. Drawing from religious inspiration, the phrases nonetheless had considerable social power, even among those who did not hold traditionally observed religious practices. Even supposedly universalistic, evangelizing religious people such as Catholics often descended into national polemics. Especially prominent, Catholic clergy in France and Germany used their religious belief to accuse the other side of being the force that was trying to destroy civilization.[16]

Most famously encapsulated in the “Spirit of 1914,” this mythologized nostalgic period of the war’s early phase retained a quasi-metaphysical meaning even among declared groups that were hostile to religion. The “Spirit of 1914” (also known as the “Ideas of 1914,” “August Days,” or “August Experiences”) encapsulated the idea that at the beginning of the war, in a headlong rush of popular devotion to a unified state aim, each combatant state believed that national unity in a just war of defense against aggression now transcended previous divides of religion, class, party and other identities. Despite recent scholarly deconstructions of the myth, the idea became powerful immediately during the war and continued long into the 20th century.[17] Although all combatant states had some version of this myth, it was most acute in Germany, the “modernist nation par excellence,”[18] which had developed so quickly into an industrialized Great Power and sacrificed so much to the war effort in an ultimately unsuccessful cause. The heightened nostalgia of 1914 corresponded to deepening desperation after 1918, as Germans sought to understand how their sacrifices could have been in vain. Most infamously, militant groups such as the Nazis used the “stab-in-the-back” myth (Dolchstosslegende) to argue that the collective will to victory was real, but it had been steadily undermined throughout the conflict by supposed “inner enemies,” particularly Jews and socialists who were portrayed as disloyal to the nation. Drawing especially on the slaughter of university students at Langemarck early in the war, nostalgic militarists argued that the only way to avenge the heroic sacrifice of the war dead was to continue fighting against the “inner enemies,” the “November criminals” who had engineered a false peace settlement that would have to be rewritten through a new round of aggressive war.[19] Nationalistically inclined religious believers, especially in Protestant circles in Germany, particularly contributed to the “origin, spread, and dissemination” of the “stab-in-the-back” myth.[20]

Bereaved and aggrieved peoples existed among both winners and losers. Even among nations that won the war, widespread bereavement could lead to aggression as survivors thought that they had to defend the war’s gains, and so honor the dead for their sacrifice.[21] Other soldiers, however, thought that the only way to honor their dead comrades was to renounce war and violence totally. Although there were transnational elements of reconciliation across national borders, especially between Germany and France, the problem of war sacrifice was most acute in Germany. Benjamin Ziemann’s study of war veterans in Germany showed the existence of a dedicated pacifist, left-wing veterans’ lobby that supported the Weimar Republic, thus challenging hegemonic collective remembrances of veterans’ groups as inherently militaristic. These veterans renounced war and denounced the soldiers and civilians who had agitated for it during 1914-1918, as well as those who sought another war to avenge the unfavorable outcome.[22] Religiously motivated popular mobilization could renounce war, too. As Gearóid Barry has shown, in the interwar era, Catholic veterans like Marc Sangnier (1873-1950) made battlefield pilgrimages while attending their peace congresses in the 1920s. Veterans thus used their Catholic faith as a source of pacifist healing. These peace congresses would be influential in laying informal networks of transnational association that helped the Christian Democratic parties foster European reconciliation in the post-1945 era.[23]

Besides the “Spirit of 1914,” combatant states used popular religious enthusiasm in a wide variety of other ways. Across national boundaries, states such as Britain and Germany tapped into medieval Christian imagery and language to reinforce the notion that combat was chivalrous, noble, and an honorable defense of tradition. By appropriating this trope, states attempted to counter the atomizing industrial brutality of modern mechanized war.[24]

Visual imagery played a huge role in the state instrumentalization of popular religious belief. Among all the powers, imagery of Christ, the cross and the saints was used on enlistment posters to get soldiers to join in the crusade to save civilization, similarly encouraging civilians to buy war bonds or become nurses. Propagandists from the Entente Powers drew heavily on images of destroyed churches and cultural sites in northern France and Belgium (such as the library at Louvain), reinforcing the notion that the enemies were barbarians bent on destroying civilization itself.[25] Battlefield legends such as the supposed crucifixion of a Canadian sergeant by German forces helped to focus outrage on the enemy, convincing soldiers that they were involved in a just war, suffering in imitation of Christ.[26]

Adaptation of Traditional Religion↑

The Great War was a moment of modernity when traditional religious practice confronted industrial destruction that threatened existing orders. Yet even in the paramount modernist centers of capital cities, traditional religious practices endured and were strengthened. Seen through working-class religion in the Southwark district of wartime London, four groups of extensive familial letter correspondence demonstrated “intensification, adaptation, and continuity rather than transformation” of pre-war religious beliefs. Family-based religious life in these cases included regular chapel attendance and a deep commitment to faith.[27]

Going into battle, Christian believers carried a copy of the Bible or short Biblical extracts with them. The opening verses of the Gospel of John were a frequently used text:

Additionally, Psalm 91, known as the “Soldier’s Psalm” in many countries, was also a prominent selection, including such passages as:

The power of scripture was especially reinforced each time the pages of text saved the soldier from being wounded by bullets or shrapnel. Significant both symbolically and physically, soldiers often carried Bibles in pockets directly over their hearts, and these practices gave a few more layers of protection in a vital area. In other cases, extracts of the verses were placed inside a scapular or amulet and worn around the soldier’s neck or carried inside a pocket, and thus physically close in times of distress.[29]

Military doctors and army psychologists observed numerous soldiers attempting to ward off bullets and shells, believing that metaphysical will and talismanic action could alter physical laws. For believers this sometimes included chanting prayers, uttering religious exclamations, and performing religious rituals such as caressing rosary beads while praying. Even when trying to minimize the legitimacy of persisting religiosity at the battlefront, most of the military psychological studies agree that in the heat of battle, soldiers’ personal beliefs, rites and actions were often explicitly Christian. At a basic level these psychological studies reported that the Lord’s Prayer, the “Our Father,” was the most frequent form of protective prayer, but Catholics also used the “Ave Maria.”[30] Although these canonical prayers were officially sanctioned forms of religiosity, masses of believers practiced their faith through these prayers in situations of extreme need. For the believing soldier, religious conviction provided a way of coping with the harsh pressures of combat. Especially in the face of repeated exposure to death, for the believing soldier who survived battle, religion also provided a rationalization of the course of events.[31]

Tensions between establishment and popular religion were perhaps most acute in the conflicts over charismatic figures with mass followings. Right in the heart of central London at the Church of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, the Anglican Vicar Dick Sheppard (1880-1937) declared the location to be the “Church of the Ever Open Door,” ministering in particular to homeless transients, beggars, the destitute, and especially to grievously wounded soldiers with nowhere else to turn. Although such actions were probably closer to the ideal of charity practiced by Jesus Christ, church authorities were troubled by Sheppard’s ideas, which, in their minds, allowed vagrants to create unsafe and unhygienic conditions in a sacred space continuously in action and thus never a place of true spiritual repose. After beginning the war as a chaplain at a military hospital in northern France, Sheppard’s personal spiritual journey led him to become a voice for the downtrodden and an outspoken pacifist in the interwar period. He advocated a non-institutional church and repeatedly clashed with religious and civil authorities over such issues as militaristic commemoration of the war dead.[32]

Potentially more troublesome and unsettling to male church leaders were female visionaries such as Claire Ferchaud (1896-1972) and Barbara Weigand (1845-1943), who implicitly or explicitly challenged traditional patriarchal structures of religion. Both of these visionary mystics drew on popular understandings of the Catholic Cult of the Sacred Heart. In their respective national contexts of France and Germany, Ferchaud and Weigand, demonstrated the transnational power of adapting a common Catholic belief, viewed both nationally and locally. Their ecstatic visions and prophesies attracted large followings of believers who granted the seers a degree of authority that threatened established churches’ claim to sole leadership. Church and state repression ensued, especially suspicious of female authority figures.[33]

Sexuality formed one of the most potent ways in which mass populations challenged traditional religious behavior, especially in extra-marital relations, some of which was state-sanctioned in the form of military brothels and rapes of defenseless citizens in occupied areas. Perhaps the case of peasant soldiers in Russia showed the most potential for destabilization of traditional sexuality, facing not only the mass destruction of Great War, but the new mores of the militantly atheistic Bolshevik regime. Studies of Russian peasant soldiers indicated that old religious codes could be violently displaced, with soldiers especially exercising newfound sexual freedom with abandon. As Leonid Heretz described it:

Of course, as Heretz pointed out, such behavior occurred in other armies, too.[34]

Particularly in Protestant countries, enthusiastic evangelicals tried to seize on the notion of the war as an opportunity for widespread social revival. The heavily Protestant contingents of the Anglophone armies in the British Commonwealth as well as the United States became prime breeding grounds for attempted moral crusades. Alcohol, gambling, and extra-marital sexual relations were all key sites of conflict between the “chapel/pub dichotomy.” Urbanization and industrialization had made these key issues in modern society’s attitude toward religion.[35] But one should not assume that religion was unpopular simply because the evangelicals’ longed-for full-scale revival never took place.

Indeed, one should resist the temptation to assume that pleasures of the flesh and material interests predominated as a matter of course. Many times they surely did, sometimes for religious believers. However, wartime behavior needs to be seen in the context of larger 20th-century trajectories. Overall, as Michael Snape has argued in his study of religion in the British Army during the era of the two world wars, it is best to view religion as a source of “diffusive Christianity,” where religious behavior formed a blurry spectrum of belief and practice in everyday life.[36]

Supernatural↑

Deeply rooted in pre-modern modes of thought, belief in supernatural phenomena reflected a two-fold power dynamic in which human agency was passive and active, and sometimes fluctuating between both poles. Fatalism encouraged the belief that destiny was preordained to the point where a soldier could not escape bullets or shells that figuratively had “his name on it.” However, in a contrary manner, other people believed that by performing carefully programmed rituals and actions such as touching a talisman, they could alter fate for the individual human being as well as others. Thus, as Jay Winter has written:

Not only outside of the established Churches, soldiers adapted religious motifs to their own personal practice, which sometimes bordered on the superstitious. The French veteran and Catholic peace activist Marc Sangnier, for instance, treasured a small wooden crucifix given to him by a nun in a convent near the Sangnier family retreat. The nun’s brother had been killed in a bombardment, and the treasured crucifix became a talisman for Marc, a visible connection to the “communion of souls.” To ward off death, Sangnier kissed the crucifix during heated times in battle.[38] The crucifix form, its reminder of the Catholic Church’s communion of all believers, and Sangnier’s personal talismanic practice underscore that official and popular religiosity were related and not necessarily opposed, based on context and individual practice.

For believers, supernatural phenomena occurred both on the battlefield and at home. Soldiers and civilians claimed to see apparitions of religious figures such as the Virgin Mary and Jesus Christ walking on battlefields, hovering over the skies or appearing at home. In one of the most famous episodes, the “Angel of Mons” appeared above the battlefield, an apparition to protect British soldiers from advancing German columns in August 1914. Drawing on medieval British memory, the tale probably drew upon legends which publicized the return of dead men from the Battle of Agincourt.[39] Similarly, on the Eastern Front in September 1914 in a forest near Augustów in modern Poland, Russian soldiers saw an apparition of the Virgin Mary with the Christ child. The legend was reported in eyewitness reports published in Russian newspapers:

In addition to apparitions of the Virgin Mother, Russian peasant soldiers often claimed to see a legendary “White Horseman,” a shadow of a rider who protected soldiers from death in forthcoming battles. Such associations tapped into a blend of Biblical tradition (Apocalyptic Battle on a White Horse found in Revelations 6:2 and 19:11-16), traditional stories of sainthood (especially the story of St. George), as well as popular myths - in this case the military cult of Mikhail Skobelev (1843-1882), a charismatic general from Russia’s campaigns in Central Asia and the Balkans in the 1870s and 1880s.[40] Religious believers on the home front would claim that a visit from a supernatural figure meant that a loved one was either protected from harm or was dead but assured of comfort in the spiritual hereafter.

More concretely, another famous episode involved the Madonna of Albert Cathedral, which became a focal point of attention near the British front lines on the Somme. Located at the top of the cathedral tower, the statue of the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child had received a direct shell hit, which bent the statue at a right angle to the church spire, hanging precipitously from the tower. The statue seemed to defy gravity, and British soldiers constructed a popular story that the war would end on the day that the Madonna finally fell to the ground. This resulted in some soldiers actually shooting at the statue to hasten its collapse, which finally occurred only in 1918 during the British bombardment of German forces that had captured Albert in 1918 as part of Erich Ludendorff’s (1865-1937) Spring Offensive.[41]

Perhaps the most famous wartime apparition of the Virgin Mary occurred in Fátima, Portugal, in 1917. The Fátima apparitions highlighted many themes of popular religion throughout the centuries: appearances to children, usually girls from poor rural backgrounds, in this case, Lúcia dos Santos (1907-2005) and her two cousins, Francisco Marto (1908-1919) and Jacinta Marto (1910-1920). The apparitions began on 13 May 1917 and continued on the 13th of every month through October 1917, eventually gathering audiences of tens of thousands of pilgrims claimed to have seen the vision. The apparitions included interpreted prophecies of an even greater war to come, visions of hell, and the need to repent for sins. The Fátima apparitions also coincided with miraculous celestial phenomena, including a “Miracle of the Sun” which involved a prophesied high-noon appearance of the sun through a veil of clouds and rain on 13 October 1917. The Fátima visions left a popular religious legacy after the Great War that influenced Catholics across the world, perhaps most notably Pope John Paul II (1920-2005). After John Paul II survived an assassination attempt on 13 May 1981, the anniversary of the original apparition, the Pope attributed his survival to the Virgin Mary’s intervention. John Paul II even made a pilgrimage to Fátima, leaving on the statue of the Virgin one of the bullets that had been removed from him.[42]

Apparitions often took the form of the ghost of a dead comrade or relative visiting believers. In the believer’s mindset, this happened to assure the living that the dead were in peace, but these apparitions could also help the living. One prominent episode of supernatural contact occurred to Will Bird (1891-1984) of the 42nd Battalion, perhaps the most famous front-line Canadian soldier. After the Battle of Vimy Ridge in April 1917, Bird sought shelter in rear-area trenches and fell asleep. He was awakened by the firm “warm hands” of his brother Steve, missing in action and presumed killed in 1915. Steve beckoned Will away from his resting place to a new location where he thought he had been sleepwalking or hallucinating; he promptly fell asleep again. When his comrades awoke Will the next day, they were amazed to find him alive: his former location had been completely destroyed by a direct hit from a high-explosive shell, which dismembered the bodies of other nearby soldiers such that his friends had been combing through the body parts attempting to identify him. Will recounted the experience to others, aware that he sounded delusional, but he believed that his dead brother had intervened to save his life.[43]

Spiritualism↑

Other Great War participants took a more active role in attempting to contact the dead, most famously through the phenomena known as spiritualism. As Jay Winter noted in his classic work, spiritualism contained both secular and religious variants. Even some avowed secularists nonetheless believed that some form of the human personality lived on after physical death. Spiritualism was a diverse phenomenon that included true believers, curious observers, the mentally deranged, and schemers attempting to defraud the gullible. Numerous individuals published volumes of materials and held séances, and spiritualistic societies carried the discussions into the public sphere. Perhaps the most famous evangelist of the spiritualist phenomenon was the creator of Sherlock Holmes, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859-1930), who lost his son, brother and brother-in-law during the war. The First World War was the “apogee of spiritualism in Europe,” which lost public appeal in the 1930s and largely did not continue into the Second World War and the post-1945 period. As Winter has argued, spiritualism and the attempt of the living to contact the dead reflected the “universality of bereavement in the Europe of the Great War and its aftermath” thus highlighting the adaptation of older more traditional forms of consoling practices, designed to allow the survivors to grieve and adequately mourn the dead.[44]

Religious spiritualism often occurred at the margins of established church doctrines, though the Catholic notion of intercessory saint cultures helped to blur boundaries. Officially, the Catholic Church denounced spiritualism and any form of attempting to contact the dead as sinful, a form of “black magic” and “superstition.” Nevertheless, individual Catholics exercised their own beliefs freely, sometimes directly contradicting their Church’s established prohibitions.[45]

Individualized Experiences and the Varieties of Folklore↑

Beyond famous personalities like Arthur Conan Doyle, ordinary soldiers and civilians used a wide variety of physical items in the belief that they could influence metaphysical reality. Talismans and amulets found numerous forms during the war, sometimes including lockets of hair, rings from loved ones or personal items associated with family members or local religious sites. Many of these objects adapted traditional forms such as the cross. The items were used for a variety of purposes, usually to ward off injury and death. While holding such objects, people uttered incantations of all kinds trying to avert disaster and return home to a state of peace.[46]

Soldiers went to war bearing religious medals of saints, while home front believers similarly invoked saints as intercessors to protect their loved ones fighting. The pre-Christian and pagan elements of Catholic and Orthodox religious cultures allowed an easier conceptual shift for religious believers to embrace a wide variety of talismanic practices designed to ward off evil.[47] Soldiers and their families carried objects of belief that blurred the boundaries between religion and superstition. The plethora of saints allowed believers to invoke the protection of specific intercessors, such as St. Barbara for artillery and miners, St. George for cavalry or St. Joseph for engineers.[48] Traditional religious items, such as rosaries, were constructed out of war materials at hand. One example was a rosary constructed by Italian prisoners of war (POWs) in the internment camp of Katzenau in Linz. The soldiers formed a cross of copper by using the fragments of detonated artillery shell casings. For the rosary chain, the POWs used cartridge casings from 6.5 mm bullets of the Mannlicher-Carcano Model 91 rifle, with rosary beads of lead balls from shrapnel shells.[49] Partially reacting against pre-war state-sponsored secularism, the case of a traditional Catholic country like Italy demonstrated that superstition blurred the line between official forms of religion and more popular religious devotion.[50]

Postcards formed one of the most visible and popular traces of religious belief on a large scale. Many showed Jesus Christ standing watch over soldiers in the trenches, sometimes leading them in battle, or comforting the dying on the battlefield. The symbolism of the dying Christ on the cross was juxtaposed in explicit comparison with dying soldiers. Other postcards highlighted religious symbols and sites, sometimes as tokens of believers’ tourism intermingled with a pilgrim’s devotion to the faith. Some postcards invoked the saints as patrons that would protect the believer and in some cases harm the enemy. More personally, postcards of churches and religious sites (even destroyed ones) served as souvenirs, allowing visitors to claim that they represented a bit of culture in a world gone mad. Such acts, demonstrated to the receiver, asserted that the visitor was a defender and respecter of culture.[51]

A wide variety of saints made an appearance in religiously themed art and literature. Some were explicitly co-opted for national purposes, such as St. Michael in the service of Germany or Joan of Arc (1412-1431) for France.[52] Indeed, Joan of Arc represented a fascinating case of a popular religious figure enshrined in French national mythology but not yet an official saint in the Catholic pantheon. Joan had become a famous figure for her steadfast devotion to keeping the English invaders off French soil, which was ironic when Joan was pressed into service for French Catholics in 1914, now alongside their English comrades. Despite French Catholicism’s self-representation as the “eldest daughter of the Church,” the Vatican had severed diplomatic relations with the French state in 1905 after the Third Republic’s passage of an official separation of church and state. Joan’s beatification had occurred in 1909, though it was the Great War that enormously helped her cause for sainthood. Through the sufferings of the First World War, and its successful conclusion, the French belief in a union sacrée and a divinely ordained victory increased dramatically. Riding on a tide of postwar religious-national enthusiasm, in 1920 Pope Benedict XV’s (1854-1922) canonization of Joan of Arc enormously helped France mend fences with the Vatican.[53] Transnational symbols and religious cults like the Sacred Heart were co-opted for national purposes, especially in Catholic France, where devotees created imagery that put the Sacred Heart image at the center of the French national flag.[54]

Popular religion drew on family bonds, solidifying connections between battlefront and home front. Highly personal stories of family belief took many forms, sometimes quite pointed and with earthy descriptions of practice. In July 1915, Minna Falkenhain wrote to her husband who was currently serving as a German soldier in Russia:

The old woman’s advice was explicit. Frau Falkenhain specified:

Religiously charged letters from home formed a major source of connection between soldiers and the home front. Variously called protective letters, chain letters, snowball letters, etc., these letters formed a part of prayer networks, often with miraculous promises, some supposedly reaching back several centuries in origin. The letters claimed that they would protect soldiers from destruction as well as harm the enemy.[56]

In the atomizing terror of the war, both in battle and at home, people responded to the stress with a variety of coping mechanisms. These methods evinced a number of social-psychological strategies that were highly individualistic. One soldier, in dread of the 13th day of the month, felt the need to kill thirteen flies in a sacrifice that would prevent him from being killed at an appointed time. He made the sacrifice and felt that this action saved his life.[57] Blurring boundaries between folk superstition and chicanery, tricksters took advantage of the gullible, selling knowingly false protective letters and amulets. Such practices began almost immediately at the beginning of the war. In mid-August 1914, German newspapers reported that Berlin women were receiving this card:

In another case in Munich, the police warned of one such scheme perpetrated by a local self-described “natural healer” (Heilkundiger) operating in the Rosenheimerstrasse, distributing papers and pamphlets described as “bullet-blessings” (Kugelsegen). Such papers declared, “Secret! A blessing against all weapons and bullets.” Selling for the price of fifty pfennigs a copy, the “healer” sold copies to numerous women, advising them to give them to their soldiers to keep in their uniforms.[58]

Late into the war, fortune-tellers made numerous appearances, especially playing on the fears of families on the home front who feared for their relatives in battle and were unable to receive regular communication from them. In such instances, prophecy earned some individuals considerable sums of money. In one notable case in Munich in February 1915, the accumulated bogus predictions of a fortune-teller caused a public outcry and a jail term of six weeks for the soothsayer, who had been charging hundreds of women five marks a prophecy for making false predictions, threatening that the women’s husbands at the front would be killed or crippled. Furthermore, tarot card readers and phrenologists in Bremen and Frankfurt were similarly punished after making too many false predictions.[59] While the analytical distinctions between religion and superstition remained blurry, individuals’ blatant untruths incurred social outrage and civil retribution, especially when the prophets made a profit.

Towards a Global History of Religion↑

Replicating historigraphical trends and respecting manageable word limits, this essay has previously concentrated on Christianity in Europe. However, religious belief was a global phenomenon, and in the future, historians must take into account developments in popular religion across the globe, particularly outside Europe. Arguing in favor of viewing the Great War as a crusade, Philip Jenkins has underscored how the Great War rearranged the religious landscape on a global level, especially the reordering of Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. In particular, some of these trends and their future importance are highlighted by examining the key classic site of the Holy Land in the Middle East as well as developments in Africa.

The Great War transformed perceptions of Jewish assimilation, reordering Jewish global settlement patterns away from Europe. Jews became perceived as either apocalyptic holy messengers of a new Zion or else projected as diabolical corrupters of existing societies, which was largely a response to war frustrations in Germany and Russia. Perhaps most influentially, Rav Abraham Isaac Kook (1865-1935), leader of Orthodox Jewish settlers in Palestine, was the rabbi of an East London synagogue in 1916. Later Kook became the Ashkenazi chief rabbi of Palestine, exercising intellectual influence on Israel’s Orthodox and ultra-Orthodox communities, especially through a rabbinic seminary that he founded in 1924 in Jerusalem, Mercaz HaRav. Kook’s most famous work, The Lights of Holiness (Orot HaKodesh), viewed the Great War in apocalyptic, eschatological terms:

Massively accelerating Jewish emigration to Palestine, the Great War caused an influx of Jewish refugees, reordering relationships between Jews and Arabs in the region, which would complicate the political disputes in the emergence of the state of Israel.[60]

Faced with traditional anti-Semitism accentuated by myths such as the “stab-in-the-back” legend, Central European Jews began to take new pride in reassessing and invigorating Jewish traditions. Martin Buber (1878-1965) and Franz Rosenzweig (1886-1929) produced a new translation of the Hebrew Bible less dependent on the Lutheran version. Eastern European Judaism, formerly scorned as backward and underdeveloped, became a source of authentic tradition, documented by Arnold Zweig (1887-1968) and Hermann Struck (1876-1944) in The Face of East European Jewry (1920). One could also point to Gershom Scholem’s (1897-1982) revitalization of the study of Kabbalistic mysticism.[61]

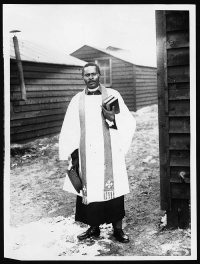

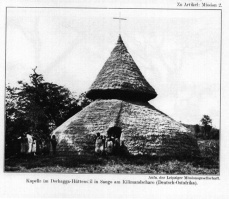

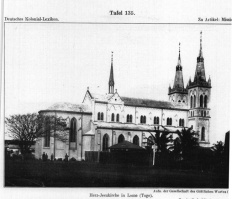

As Philip Jenkins has written, far from being “colorful irrelevancies,” the Great War in Asia and Africa was central to the global reordering that continues to the present day. Especially grounded in conflicts between Christianity and Islam, the ideologically charged attempts at fomenting revolution and insurgency made the Great War an epic moment with important legacies.[62] For the development of a truly global Christianity, the demographic shifts of religious believers were most dramatic in Africa. There, Christianity represented a vibrant religious spectrum, sometimes blending native pagan traditions, and at the other extreme end composed of a hardcore dogmatic assertive clergy that would eventually conduct missionary work in Europe and North America, as in the case of the Pentecostal sect of the Redeemed Christian Church of God. Through the influence of charismatic preachers, Christianity developed a mass appeal in Africa during and after the Great War, often beginning as a semi-secretive form of youth rebellion against established traditional structures, whether native or colonial.[63] The spread of religious ideas could also be seen in reactions to the global spread of the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918. Religious believers saw the Spanish Flu as a plague, a scourge from God, punishing humanity for the sinfulness of the war. Faith and flu were linked, expanding along colonial transportation routes such as the British base at Freetown, Sierra Leone, where both disease and faith spread through West Africa via colonial networks of exchange.[64]

Waging a truly global war, the Great Powers drew upon their existing colonial resources, especially in recruiting soldiers and laborers. Perhaps most famously, Indian and Senegalese soldiers fought for Britain and France, respectively. Religious ideologies were used to mobilize subject populations, bringing religion explicitly into the political realm.[65] Reacting against centuries of European racism and oppression, the Great War furthered ideas of anti-colonial nationalism, with religious leaders seizing on the “Wilsonian moment” and the promise of an imminent better world.[66] A trained Baptist preacher declaring the need for black liberation, John Chilembwe (1871-1915) became the national hero of Malawi after leading a revolt of 200 rebels who attacked local plantations in 1915. Suffering from influenza, which only added realism for her listeners, the millenarian Nontetha Nkwenkwe (1875-1935) from the Eastern Cape warned of God spreading disease as punishment for all society. It was a new development in African religion that many prophets framed their visions in Christian terms, such as in the way they perceived the Spanish Flu pandemic.[67] At the time, these revolts were exceptional but hinted at things to come. In religious terms the mostly non-political critiques of colonial order were usually non-violent before the 1950s, but these developments laid the ideological groundwork for aggressive de-colonization in later decades.[68]

Similarly, the Great War in the Middle East transformed the global order, and should be a primary episode in the roots of a conflict that has received increased attention in political and media discourse in the aftermath of the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001. The Great War destroyed the Caliphate that had existed since the successors of the Prophet Muhammed (ca. 570-632). European intervention and subversion, most famously the raids of Thomas Edward Lawrence (1888-1935) of Arabia and the “Arab Revolt” of 1916, helped destroy the Ottoman Empire, but in 1914 the Middle East was still geopolitically weak. However, this would change rapidly with the exploitation of newly discovered oil resources.[69]

Attempting to stabilize the region, European diplomatic rearrangements in fact laid the groundwork for future conflicts, most infamously through the Sykes-Picot Agreement (1916) and the Balfour Declaration (1917). These diplomatic maneuverings created a new, artificial and highly unstable geopolitical order in the modern Middle East, one which would become even more violently destructive after the establishment of the state of Israel in the aftermath of the Second World War.[70] In the 19th century, wandering preachers such as Dschamal ad-Din Al-Afghani (1838-1897) spread the seeds of reform movements, preaching the need for Muslim unity. During the Great War, at the Central Asian crossroads of the decaying Russian and Ottoman Empires, atheistic Bolsheviks fought against fundamentalist Muslims in an extreme case of a “clash of civilizations.” Besides these sometimes-forgotten military conflicts, the ideological percolation would continue, setting up future conflicts. This would lead to the violent extremism of the Muslim Brotherhood (Ikhwan al-Muslimun), founded in 1928 by Hasan al-Banna (1906-1949) and drawing on the theorizing of Sayyid Qutb (1906-1966). Such groups proclaimed the need for a restored theocratic Caliphate ruling by sharia law, even to the point of killing self-professed Muslims that they considered to be less than pure. As Jenkins wrote, “the movements they represented can be traced to the post-1918 spiritual crisis that left the Muslim world with no obvious center or focus of loyalty.”[71] Such developments would find expression in diverse groups like al-Qaeda and the Islamic State (IS).

Conclusion↑

In his famous Gifford Lectures, William James referred to the “Varieties of Religious Experience,” yet the Jamesian plurality of understanding is often forgotten when discussing religion during the Great War.[72] Long dominated by the clergy’s polarizing war rhetoric, the cultural history of the war is now a much more complicated picture beyond the official religious rhetoric in the public sphere. Studies of popular religion will continue to represent the common everyday experiences of believers, adding new realms of representation and subjectivity. In particular, future historians will have to contextualize developments in Europe in light of new findings of popular religiosity across the globe. Befitting the subject matter, examinations of popular religion during the war will remain necessarily hazy and indeterminate, shrouded with an aura of mystery. Nevertheless, popular religion will remain vitally important for discussing believers’ motivations and mindsets during the Great War.

The avant-garde experience of disillusioned European cultural elites during the Great War must not remain the Great War’s master narrative of cultural history regarding religion. If one considers European secularization as exceptional, or at least multifaceted, rather than normative, the Great War highlights the vibrant religious spectrum and the changes that began in 1914, which helped to shape the modern religious landscape, especially the rise of a Global South and the sociopolitical importance of the Middle East. Religion as a source of both war- and peacemaking will continue. Colonial legacies, nationalist identities, minority persecution, religion’s relation to human rights, and the constant give-and-take between religious liberty and security all highlight the persistence of religiosity as a major factor of global popular belief and practice. Transnational and entangled colonial histories ensure that religious mobilization and popular belief will remain key questions for understanding the Great War’s place in global history.

Patrick J. Houlihan, University of Chicago

Reviewed by external referees on behalf of the General Editors

Notes

- ↑ I would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers from 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War for their helpful comments; I am responsible for errors and interpretation. See also the essay, “The Churches” in 1914-1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War.

- ↑ Houlihan, Patrick J.: Catholicism and the Great War. Religion and Everyday Life in Germany and Austria-Hungary, 1914-1922, Cambridge 2015.

- ↑ Taylor, John: The Future of Christianity, in: McManners, John (ed.): The Oxford History of Christianity, Oxford 1993, pp. 644-83.

- ↑ There is extensive literature on the secularization thesis. Despite wide-ranging reassessments of the valence of popular religion and modern culture on a global level, secularization remained a master narrative in understanding the story of modern Europe, largely because no single master counternarrative has emerged. For an introduction, see Cox, Jeffrey: Master Narratives of Religious Change, in: McLeod, Hugh / Ustorf, Werner (eds.): The Decline of Christendom in Western Europe, 1750-2000, Cambridge 2003, pp. 201-217.

- ↑ Cork, Richard: A Bitter Truth. Avant Garde Art and the Great War, New Haven 1994.

- ↑ Gregory, Adrian: Beliefs and Religion, in: Winter, Jay (ed.): The Cambridge History of the First World War, Cambridge 2014, vol. 3, pp. 418-44.

- ↑ Korff, Gottfried (ed.): Alliierte im Himmel. Populare Religiosität und Kriegserfahrung, Tübingen 2006.

- ↑ Cameron, Euan: Enchanted Europe. Superstition, Reason, and Religion, 1250-1750, Oxford 2010; Thomas, Keith: Religion and the Decline of Magic. Studies in Popular Beliefs in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century England, New York 1971.

- ↑ Graf, Friedrich Wilhelm: “Dechristianisierung.” Zur Problemgeschichte eines kulturpolitischen Topos, in: Lehmann, Hartmut (ed.): Säkularisierung, Dechristianisierung, Rechristianisierung im neuzeitlichen Europa, Göttingen 1997, p. 66.

- ↑ Becker, Annette: Faith, Ideologies, and the “Cultures of War,” in: Horne, John (ed.): A Companion to World War I, Chichester 2010, p. 241.

- ↑ Quoted in Ellis, John: Eye-Deep in Hell. Trench Warfare in World War I, Baltimore 1989, p. 9.

- ↑ Quoted in Ferguson, Niall: The Pity of War, London 1998, p. xxvii.

- ↑ Fussell, Paul: The Great War and Modern Memory, Oxford 1975, p. 240.

- ↑ Quoted in Ferguson, Pity of War 1998, p. xxx.

- ↑ Statistics and quote in Schweitzer, Richard: The Cross and the Trenches. Religious Faith and Doubt among British and American Great War Soldiers, Westport 2003, pp. 227ff.

- ↑ Baudrillart, Alfred (ed.): La Guerre allemande et le catholicisme. Documents photographiques illustrant la conduite respective des armées allemande et française à l'égard de l'Église Catholique, Paris 1915; Pfeilschifter, Georg (ed.): Deutsche Kultur, Katholizismus und Weltkrieg. Eine Abwehr des Buches, La guerre allemande et le catholicisme, Freiburg im Breisgau 1915.

- ↑ Bruendel, Steffan: Volksgemeinschaft oder Volksstaat. Die “Ideen von 1914” und die Neuordnung Deutschlands im Ersten Weltkrieg, Berlin 2003; Verhey, Jeffrey: The Spirit of 1914. Militarism, Myth, and Mobilization in Germany, Cambridge 2000.

- ↑ Eksteins, Modris: Rites of Spring. The Great War and the Birth of the Modern Age, Boston 1989, p. xvi.

- ↑ Krumeich, Gerd: Die Dolchstoß-Legende, in: François, Etienne / Schulze, Hagen (eds.): Deutsche Erinnerungsorte, Munich 2001, pp. 1585-99.

- ↑ For extensive examination of the religious dimensions of the “stab-in-the-back” myth, see Barth, Boris: Dolchstoßlegenden und politische Desintegration. Das Trauma der deutschen Niederlage im Ersten Weltkrieg, Düsseldorf 2003, pp. 150-71, 340-59, 555.

- ↑ Watson, Alexander/Porter, Patrick: Bereaved and Aggrieved. Combat Motivation and the Ideology of Sacrifice in the First World War, in: Historical Research 83/219 (2010), pp. 146-64.

- ↑ Ziemann, Benjamin: Contested Commemorations. Republican War Veterans and Weimar Political Culture, Cambridge 2013.

- ↑ Barry, Gearóid: The Disarmament of Hatred. Marc Sangnier, French Catholicism and the Legacy of the First World War, 1914-45, New York 2012, p. 45.

- ↑ Frantzen, Allen J.: Bloody Good. Chivalry, Sacrifice, and the Great War, Chicago 2004; Goebel, Stefan: The Great War and Medieval Memory. War, Remembrance, and Medievalism in Britain and Germany, 1914-1940, Cambridge 2007.

- ↑ Kramer, Alan: Dynamic of Destruction. Culture and Mass Killing in the First World War, Oxford 2007.

- ↑ Vorsteher, Dieter: Bilder für den Sieg. Das Plakat im Ersten Weltkrieg, in: Rother, Rainer (ed.): Die letzten Tage der Menschheit. Bilder des Ersten Weltkrieges, Berlin 1994, pp. 149-62.

- ↑ Gregory, Adrian/Becker, Annette: Religious Sites and Practices, in: Winter, Jay/Robert, Jean-Louis (eds.): Capital Cities at War. Paris, London, Berlin, volume 2, A Cultural History, Cambridge 2007, pp. 400-03.

- ↑ Senior, Donald / Collins, John J. (eds.): The Catholic Study Bible, 2nd edition, New York 2006, pp. 1403, 749f.

- ↑ Bächtold, Hanns: Deutscher Soldatenbrauch und Soldatenglaube, Strassburg 1917, p. 17.

- ↑ Ludwig, Walter: Beiträge zur Psychologie der Furcht im Kriege, in: Stern, William/Lipmann, Otto (eds.): Beiträge zur Psychologie des Krieges, Beihefte zur Zeitschrift für angewandte Psychologie, Heft 21, Leipzig 1920, pp. 170f; Plaut, Paul: Psychographie des Kriegers, in: Stern / Lipmann, Beiträge zur Psychologie 1920, p. 74. See also Scholz, Ludwig: Seelenleben des Soldaten an der Front. Hinterlassene Aufzeichnungen des im Kriege gefallenen Nervenarztes, Tübingen 1920, p. 180.

- ↑ Watson, Alexander: Enduring the Great War. Combat, Morale and Collapse in the German and British Armies, 1914-1918, Cambridge 2008.

- ↑ Gregory/Becker, Religious Sites 2007, p. 401.

- ↑ Schlager, Claudia: Kult und Krieg. Herz Jesu – Sacré Cœur – Christus Rex im deutsch-französischen Vergleich, 1914-1925, Tübingen 2011, pp. 290-306.

- ↑ Heretz, Leonid: Russia on the Eve of Modernity. Popular Religion and Traditional Culture under the Last Tsars, Cambridge 2008, pp. 222ff.

- ↑ Schweitzer, The Cross 2003, pp. 185-243.

- ↑ Snape, Michael: God and the British Soldier. Religion and the British Army in the First and Second World Wars, London 2005, pp. 1-58.

- ↑ Winter, Jay M.: The Experience of World War I, London 1988, p. 149.

- ↑ Barry, Disarmament 2012, pp. 44f.

- ↑ Besides the flood of contemporary literature, see Clarke, David: The Angel of Mons. Phantom Soldiers and Ghostly Guardians, Hoboken 2004.

- ↑ For a folk art painting of the Augustów apparition, and the newspaper quote, see Rother, Rainer (ed.): Der Weltkrieg 1914-1918. Ereignis und Erinnerung, Wolfratshausen 2004, pp. 202f. For a contextualization of the Augustów apparition as well as the “White Horseman,” see Heretz, Russia 2008, pp. 210-18.

- ↑ Winter, Experience 1988, p. 149.

- ↑ Jenkins, Philip: The Great and Holy War. How World War I Became a Religious Crusade, New York 2014, pp. 170ff, 370.

- ↑ Cited in Cook, Tim: Grave Beliefs. Stories of the Supernatural and the Uncanny among Canada’s Great War Trench Soldiers, in: Journal of Military History 77/2 (2013), pp. 521f. For Bird’s narrative, see Bird, Will: Ghosts Have Warm Hands, Toronto 1968, pp. 38-41.

- ↑ Winter, Jay: Sites of Memory, Sites of Mourning. The Great War in European Cultural History, Cambridge 1995, pp. 54-77.

- ↑ Houlihan, Catholicism 2015, pp. 234f.

- ↑ Grabinski, Bruno: Das Übersinnliche im Weltkriege. Merkwürdige Vorgänge im Felde und allerlei Kriegsprophezeiungen, Hildesheim 1917; Grabinski, Bruno: Neuere Mystik. Der Weltkrieg im Aberglauben und im Lichte der Prophetie, Hildesheim 1916; Hellwig, Albert: Weltkrieg und Aberglaube. Erlebtes und Erlauschtes, Leipzig 1916.

- ↑ Houlihan, Catholicism 2015, p. 11.

- ↑ Alzheimer, Heidrun (ed.): Glaubenssache Krieg. Religiöse Motive auf Bildpostkarten des Ersten Weltkriegs, Bad Windsheim 2009, pp. 145-64.

- ↑ For a picture and description of the components, see Rother, Der Weltkrieg 2004, p. 199.

- ↑ Stiaccini, Carlo: L’anima religiosa della Grande Guerra. Testimonianze popolari tra fede e superstizione, Roma 2009.

- ↑ Alzheimer, Glaubenssache Krieg 2009.

- ↑ Beil, Christine et al.: Populare Religiosität und Kriegserfahrungen, in: Theologische Quartalsschrift 182/4 (2002), pp. 298-320.

- ↑ Becker, Annette: War and Faith. The Religious Imagination in France, 1914-1930, translated by Helen McPhail, Oxford 1998.

- ↑ Schlager, Kult und Krieg 2011.

- ↑ Letter from 16 July 1915, Minna Falkenhain to her husband, quoted in Schumann, Frank (ed.): “Zieh Dich warm an!” Soldatenpost und Heimatbriefe aus zwei Weltkriegen. Chronik einer Familie, Berlin 1989, pp. 51f.

- ↑ Houlihan, Catholicism 2015, pp. 148f.

- ↑ Watson, Enduring the Great War 2008, p. 98.

- ↑ Grabinski, Neuere Mystik 1919, pp. 61f. See also Houlihan, Catholicism 2015, p. 149.

- ↑ Hellwig, Weltkrieg und Aberglaube 1916, pp. 147-50. See also Houlihan, Catholicism 2015, p. 149.

- ↑ Quoted in Jenkins, Great and Holy War 2014, pp. 251ff.

- ↑ Jenkins, Great and Holy War 2014, p. 260.

- ↑ Jenkins, Great and Holy War 2014, p. 285.

- ↑ Jenkins, Great and Holy War 2014, pp. 317-24. In 1900, there were 10 million Christian believers on the African continent, less than 10 percent of the total population. By 2000, this number had grown to 360 million or 46 percent, and it is estimated that by 2050, 1 billion souls, one-third of the Christian population globally, will be Africans.

- ↑ Jenkins, Great and Holy War 2014, p. 324.

- ↑ Jenkins, Great and Holy War 2014, p. 282.

- ↑ Manela, Erez: The Wilsonian Moment. Self-Determination and the International Origins of Anticolonial Nationalism, Oxford 2009.

- ↑ Jenkins, Great and Holy War 2014, pp. 269f, 315f.

- ↑ Jenkins, Great and Holy War 2014, pp. 329ff.

- ↑ Jenkins, Great and Holy War 2014, pp. 333-36.

- ↑ Fromkin, David: A Peace to End All Peace. The Fall of the Ottoman Empire and the Creation of the Modern Middle East, New York 1989.

- ↑ Jenkins, Great and Holy War 2014, pp. 340-58, quote from p. 357.

- ↑ James, William: The Varieties of Religious Experience, New York 1982 [1902].

Selected Bibliography

- Barry, Gearóid: The disarmament of hatred. Marc Sangnier, French Catholicism and the legacy of the First World War, 1914-45, New York 2012: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Becker, Annette: War and faith. The religious imagination in France, 1914-1930, Oxford; New York 1998: Berg.

- Becker, Annette: Faith, ideologies, and the 'cultures of war', in: Horne, John (ed.): A companion to World War I, Chichester; Malden 2010: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 234-247.

- Beil, Christine et al.: Populare Religiosität und Kriegserfahrungen, in: Theologische Quartalsschrift 182/4, 2002, pp. 298-320

- Cook, Tim: Grave beliefs. Stories of the supernatural and the uncanny among Canada's Great War trench soldiers, in: Journal of Military History 77/2, 2013, pp. 521-542.

- Gregory, Adrian / Becker, Annette: Religious sites and practices, in: Winter, Jay / Jean-Louis Robert (eds.): Capital cities at war. Paris, London, Berlin, 1914-1919. A cultural history, volume 2, Cambridge; New York 1997: Cambridge University Press, pp. 383-427.

- Gregory, Adrian: Beliefs and religion, in: Winter, Jay (ed.): The Cambridge history of the First World War. Civil society, volume 3, New York 2014: Cambridge University Press, pp. 418-444.

- Heretz, Leonid: Russia on the eve of modernity. Popular religion and traditional culture under the last Tsars, Cambridge; New York 2008: Cambridge University Press.

- Houlihan, Patrick J.: Catholicism and the Great War. Religion and everyday life in Germany and Austria-Hungary, 1914-1922, Cambridge 2015: Cambridge University Press.

- James, William: The varieties of religious experience, New York 2010: Library of America; Penguin Group.

- Jenkins, Philip: The great and holy war. How World War I became a religious crusade, New York 2014: HarperOne.

- Korff, Gottfried (ed.): Alliierte im Himmel. Populare Religiosität und Kriegserfahrung, Tübingen 2006: Tübinger Vereinigung für Volkskunde.

- Kramer, Alan: Dynamic of destruction. Culture and mass killing in the First World War, Oxford; New York 2007: Oxford University Press.

- Madigan, Edward: Faith under fire. Anglican army chaplains and the Great War, Basingstoke; New York 2011: Palgrave Macmillan.

- McManners, John: The Oxford history of Christianity, Oxford; New York 1993: Oxford University Press.

- Schlager, Claudia: Kult und Krieg. Herz Jesu - Sacré Cœur - Christus Rex in deutsch-französischen Vergleich 1914 - 1925, Tübingen 2011: Tübinger Vereinigung für Volkskunde e.V..

- Schweitzer, Richard: The cross and the trenches. Religious faith and doubt among British and American great war soldiers, Westport 2003: Praeger Publishers.

- Snape, Michael F.: God and the British soldier. Religion and the British Army in the First and Second World Wars, London; New York 2005: Routledge.

- Stiaccini, Carlo: L'anima religiosa della Grande Guerra. Testimonianze popolari tra fede e superstizione, Rome 2009: Aracne.

- Thomas, Keith: Religion and the decline of magic. Studies in popular beliefs in sixteenth and seventeenth century England, New York 1997: Oxford University Press.

- Watson, Alexander: Enduring the Great War. Combat, morale and collapse in the German and British armies, 1914-1918, Cambridge; New York 2008: Cambridge University Press.

- Winter, Jay: The experience of World War I, London 1988: Macmillan.

- Winter, Jay: Sites of memory, sites of mourning. The Great War in European cultural history, Cambridge 2000: Cambridge University Press.