Introduction↑

The German invasion of Belgium, between August and October 1914, led to the flight of more than 1.5 million Belgian civilians. Several thousand settled in the small part of Belgium that remained unoccupied but the vast majority sought asylum abroad, essentially in the Netherlands, France or Great Britain. The migration destination was usually determined by the nearest border: most of the inhabitants of the provinces Hainaut and West Flanders tried to reach France, while thousands from Liège, Antwerp and East Flanders travelled to the Netherlands or swelled the ranks of those hoping to flee the advancing German troops by crossing the English Channel. The end of the German military advance in Belgium brought the stream of refugees to a stop. Only a few thousand Belgians continued to cross the Dutch border secretly: mainly young men wishing to join the army or find jobs abroad.

According to estimates, the number of Belgian refugees in the Netherlands reached 1 million in October 1914, but the number subsequently decreased rapidly under pressure from the Dutch authorities, falling to about 100,000 by 1916. The refugees were joined by some 30,000 Belgian soldiers, whom the Dutch authorities were compelled to intern in various camps scattered around the country. Another 200,000 Belgian refugees reached the coast of Britain in 1914, but their number gradually declined and remained stable at around 150,000. Due to the evacuation of Flemish civilians from the combat zone, the number of Belgians taking refuge in France increased throughout the conflict to reach 325,000 before the armistice in November 1918. In total more than 600,000 Belgians – some 8 percent of the Belgian population – settled abroad during the First World War.

Humanitarian Efforts↑

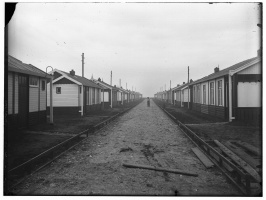

In each of the three countries involved, the arrival of Belgian refugees led to unprecedented humanitarian action. The immense scale of the relief efforts was prompted by the concern that the invasion of Belgium, in violation of international law, caused among the public of the affected nations. In France, Belgians received the same benefits from the state as the refugees from north and eastern France. This financial help was maintained throughout the war and enabled the poorest refugees to avoid utter destitution. In Great Britain, committees sprang up all around the country to help resettle refugee families, either with host families or in boarding houses set up especially for this purpose. In the Netherlands, the assistance to Belgian populations was very generous but more limited in time. At the end of 1914, destitute refugees were sent to large camps euphemistically referred to as “havens” or “Belgian villages”.

Refugees as Additional Manpower↑

In France and Great Britain, the long months of war saw a gradual dwindling of the support offered to all refugees. Many had no other choice but to find a job. They were suddenly seen as a useful source of substitute manpower amid a severely depleted local workforce. In France, more than 22,000 refugees were put to work in a total of 1,600 companies, with a further 15,000 farmers sent to work on the land. In Britain in 1918, with about 30,000 Belgians employed in ammunition factories, including more than 7,000 women, the refugees represented one of the largest foreign workforces in the country. Unlike in France and Great Britain, unemployment was very high among Belgian refugees in the Netherlands. In light of the economic crisis gripping the country, Dutch trade unions and many municipal authorities discouraged the hiring of Belgian refugees or even endeavoured to prevent them from competing with Dutch workers.

In Great Britain and, to a lesser extent, France, the search for jobs prompted many refugees to settle in heavily populated working-class areas. In these communities, the refugees kept to themselves and felt a strong desire to maintain their traditional way of life, achieving only limited integration. Through the creation of dozens of choirs, theatre groups and various clubs, they tried to strengthen the bonds to their homeland and to keep alive the hope of an imminent return.

After the War↑

The proclamation of the armistice in November 1918 gave rise to great expectations among the refugees, the vast majority of whom were clearly impatient to return to their families and property after years of absence. By July 1919, most of the Belgians who had taken refuge in the Netherlands had returned home; very few decided to remain permanently. The British authorities, deeply concerned with the impending economics crisis threatening to engulf the country, immediately took measures to repatriate the refugees. By mid-1919, almost all Belgians who had resided in Britain had left the country. France, bled dry by four year of war, did not view the repatriation of Belgian refugees as a pressing issue. A few thousand settled permanently in France, especially in Normandy, where many were granted fertile farmland. All in all, however, almost all of the hundreds of thousands of Belgian refugees returned to their homeland after the war.

After the war, many refugees were met with indifference or even hostility. Some were treated as cowards. Many considered them privileged people or deserters who had failed to demonstrate sufficient courage in the face of the enemy. Their contribution to the war effort was judged marginal at best. This was evident in the commemorations organised after the war. There was no place for refugees in the Belgian memory of the war. As a result, Belgian historians and citizens rapidly forgot the refugees’ war experience.

Michaël Amara, National Archives of Belgium

Section Editor: Emmanuel Debruyne

Selected Bibliography

- Amara, Michaël: Des Belges à l'épreuve de l'Exil. Les réfugiés de la Première Guerre mondiale. France, Grande-Bretagne, Pays-Bas, 1914-1918, Brussels 2008: Éditions de l'Université de Bruxelles.

- Cahalan, Peter: Belgian refugee relief in England during the Great War, New York 1982: Garland.

- Roodt, Evelyn de: Oorlogsgasten. Vluchtelingen en krijgsgevangenen in Nederland tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog (War guests. Refugees and prisoners of war in the Netherlands during the First World War), Zaltbommel 2000: Europese Bibliotheek.